Tokyo, 1910s • Shinjuku's Lost Paradise (1)

A pond lost to history tells Tokyo’s story…

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This is Part 1 of an essay about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

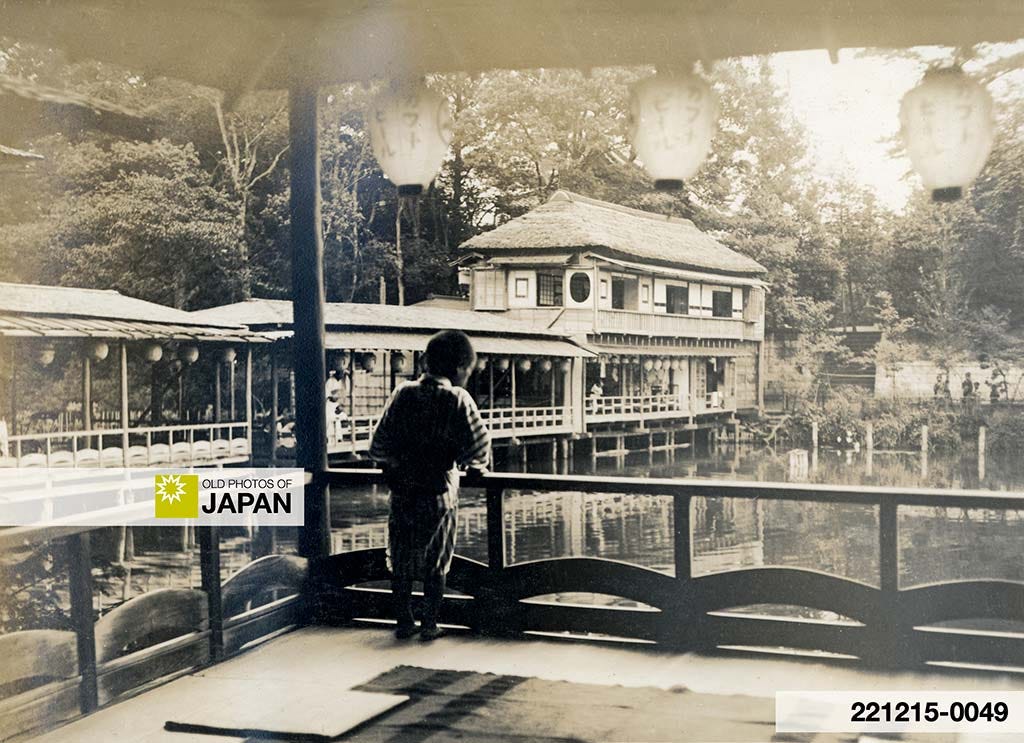

Sheltering trees, romantic open teahouses—the idyllic Jūnisō Pond was for centuries a celebrated city escape. Tokyo’s growth birthed it. Then greedily swallowed it all up 300 years later.

Jūnisō was more than just a pretty pond. Since 1590—when Tokugawa Ieyasu started building his power base on the marshy shore of what is today Tokyo Bay—Jūnisō almost perfectly reflected Tokyo’s many transformations. By learning about Jūnisō, one discovers the story of Tokyo. I can’t think of another place in Tokyo that inhabits such a representative historical space, yet is barely known.

Much has been written about Jūnisō in Japanese, but it is always the same story, and features several myths. This has made Jūnisō simultaneously known and unknown. To grasp Jūnisō’s true significance I had to dig deep into historical sources. I hope that you will find the story that emerged as fascinating as I did.

This essay consists of five parts. This is Part 1.

The location of this relaxed rural scene from the 1910s may surprise you. Today this is Nishi-Shinjuku, Tokyo’s densely built skyscraper district famous for architectural legend Kenzo Tange’s iconic Tokyo Metropolitan Government Buildings. The two images below are separated by a mere century.

Rural Bliss

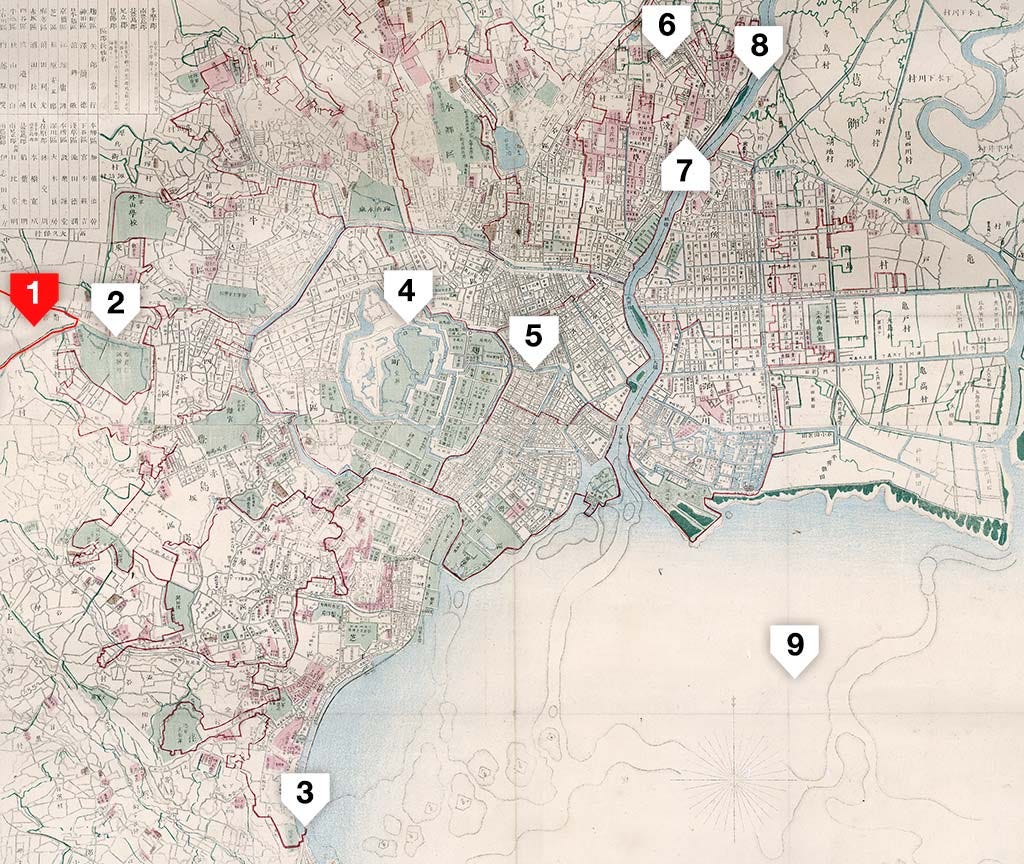

Nishi-Shinjuku used to be called Tsunohazu Village (角筈村) and lay outside the city’s boundaries. Most of it was squeezed between two major highways, the Ōme and Kōshū Kaidō (marked red on the map).1 They separated into different directions from the Naitō Shinjuku way-station, opened in 1699 (Genroku 12).

Until the late 1890s Tsunohazu was a distinctively rural district, defined by rice fields, groves, and tea fields. In winter, foxes howled in the forest.2 When Shinjuku railway station opened in 1885 (Meiji 18) it serviced 50 passengers a day. On rainy days there were none.3 Tsunohazu was described as “lonely” and “desolate”.4

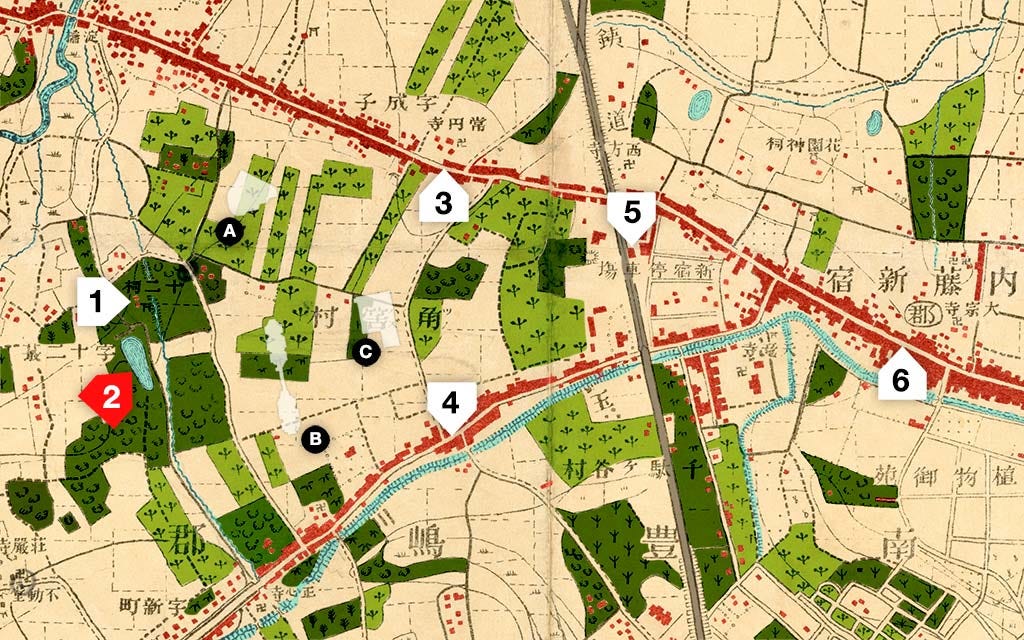

Even more surprising, today’s concrete jungle used to be lush tea country. To illustrate how many tea fields there were, I have colored them light green on the 1894 (Meiji 27) map below, which was surveyed in 1880 (Meiji 13). Dark green denotes groves. Most white areas were rice paddies.

The tea fields were surprisingly large. Note the outlines of the Hilton Hotel, Tokyo Metropolitan Government Buildings and Keio Plaza Hotel at their actual scale and current locations. Compared to the tea plantations they look puny.

Famed naturalist novelist Katai Tayama (田山花袋, 1872–1930) lived nearby. His novel Time Passes On (1916) describes how Tsunohazu changed during the Meiji Period (1868–1912). Tea fields play a major role in the novel:5

One day it was clear and sunny after the rains. The buds would grow too long if they weren’t picked that day, so after finishing her breakfast, Okane closed the back door, picked up a basket, covered her hair with a towel, and headed to the tea field beneath the plum trees. The tea leaves were still damp from the rain and were growing a pleasant green. The morning sun filtered through the green leaves and shone brightly all around.

Katai Tayama, Time Passes On (1916)

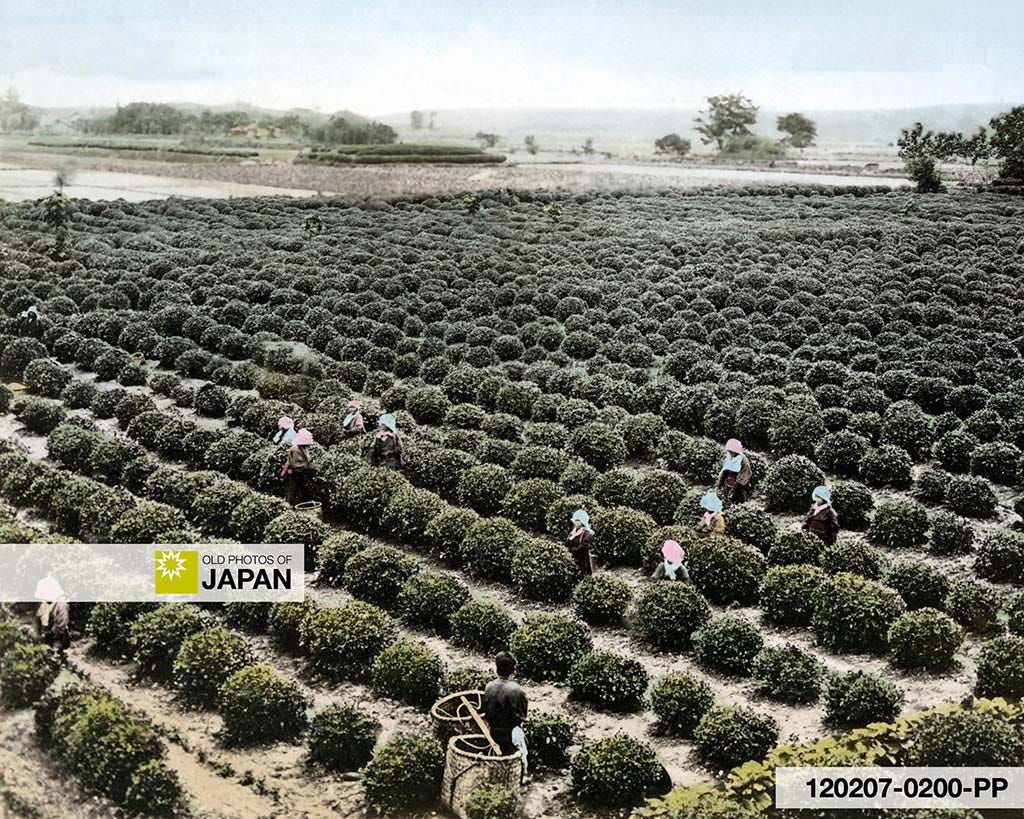

Tayama’s novel describes how during the tea season, Tsunohazu’s vast fields of green tea bushes were dotted with the white towels that the female tea-pickers wrapped around their hair. Their songs filled the air.6

Unfortunately, I have found no photos of Tsunohazu’s tea fields. But they likely looked similar to this tea plantation in Uji, Kyoto:

Place of Beauty

Tsunohazu, however, did not become famous for its tea. It became famous for Jūnisō Pond (十二社池) and two waterfalls, clustered around a small thatched shrine known as Kumano Jūnisō Gongen (熊野十二所権現社).7

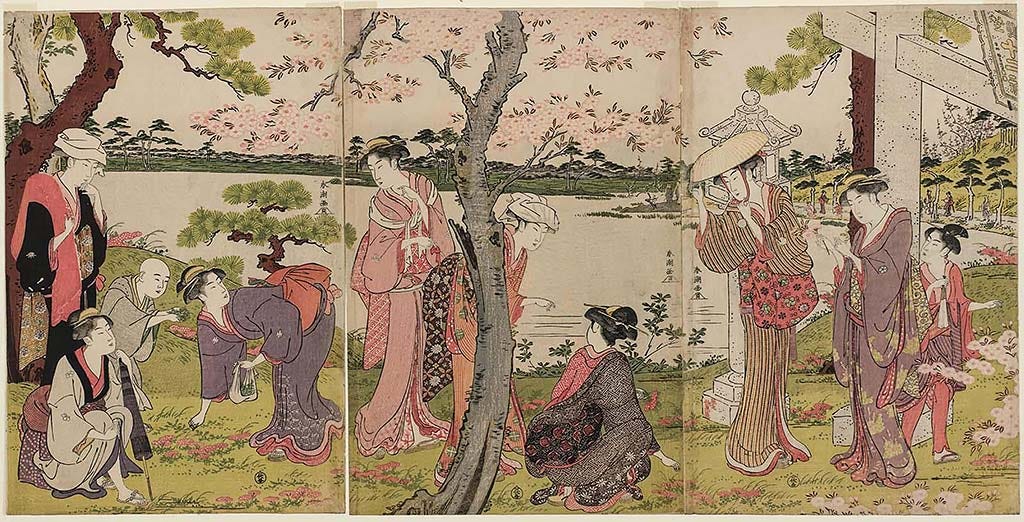

From the early 1700s on, Jūnisō Pond was celebrated as a place of pure natural beauty. Every season brought different colors—plum and cherry trees blossomed from March, irises decorated the shore in early June, maple leaves brought festive autumn colors in November. The shadows of countless scarlet carp could be seen in the water, while pine needles scattered across the pond’s surface.

The quiet shrine was surrounded by a thick forest of aged pine, cedar, fir, and oak. In summer, it embraced visitors with the sounds of cicadas, rushing water, and millions of rustling leaves. Even on the hottest days it felt cool.8

In contrast with the top photo from the 1910s, there were initially few teahouses. The focus was on the natural beauty of Jūnisō.

Jūnisō’s remote location added to the attraction. It was inconvenient—yet thanks to the nearby highways accessible to the determined. It was close enough to the city for a day trip—yet far enough to keep away boisterous crowds.

These elements made Jūnisō “the perfect place for the cultured person,” wrote the Buddhist monk Fukyū Dōjin (負笈道人, 1778?–1851). He described Jūnisō as an almost sacred natural sanctuary where “worldly desires vanish”.9

When there are too many people it ruins the atmosphere, and drunk people spoil the scenery. In such a condition how could one possibly enjoy nature in a relaxed and pure state of mind?

In contrast, in this place, when the cherry blossom is in full bloom, one feels as if one has arrived in the land of Buddha. And when the spring leaves shine with a soft fresh green, the whole body feels renewed. When one hears the songs of insects in the light of the bright moon, one catches a glimpse of a state of enlightenment. And when one sees the hills shining silver with snow, all worldly desires vanish.

Fukyū Dōjin (1851)

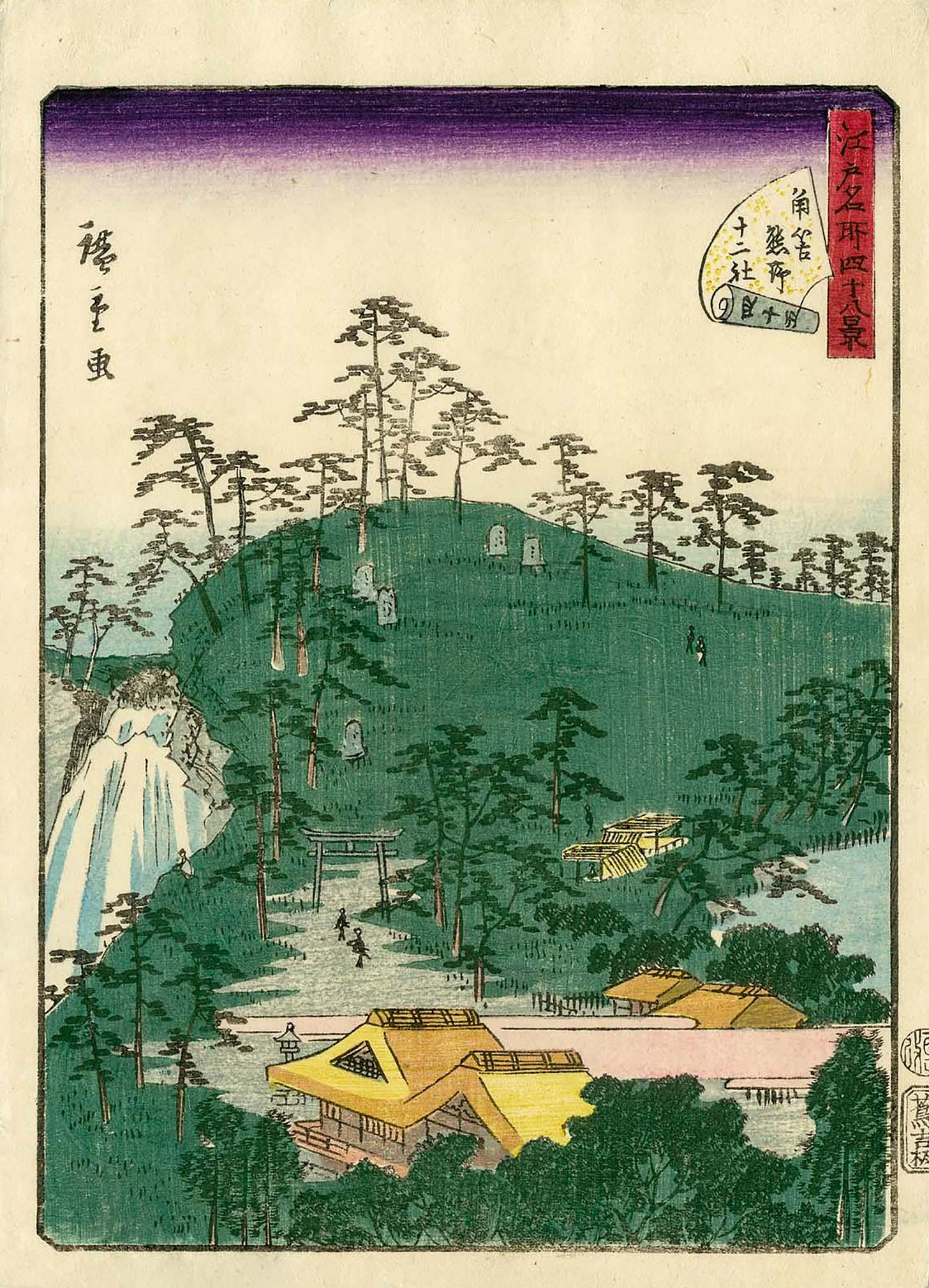

Jūnisō’s beauty inspired renowned artists like Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Hokusai (1760–1849)—thousands of prints were sold of the pond and falls. Many can still be admired at the world’s most prestigious museums.

Man-made

Remarkably, the natural beauty that inspired artists and moved Fukyū to religious rapture was all man-made. It sprung into being because shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) selected Edo to build his power base.

Continue to Part 2 : How Tokugawa Ieyasu’s ambitions gave birth to Jūnisō’s natural beauty.

Notes

On Jūnisō’s North was the Ōme Kaidō (青梅街道), the main highway to Kōfu in Yamanashi Prefecture. On its South lay the Kōshū Kaidō (甲州街道), to Suwa in Nagano Prefecture. The latter road was one of the official Gokaidō (五街道, Five Routes) connecting Edo with the rest of Japan. The area became part of Tokyo City in 1932 (Showa 7).

泉鏡花(1900)『政談十二社 』in 『新宿と文学―そのふるさとを訪ねて』, 東京都新宿区教育委員会 (1968).

日本国有鉄道新宿駅 (1985).『新宿駅100年のあゆみ : 新宿駅開業100周年記念』日本国有鉄道新宿駅, 20–21.

川本三郎(2003).『 郊外の文学』Tokyo: 新潮社, 62–63. 「寂しい」「荒涼たる」。

The text on the 1851 Kumano Jinja memorial stone at the shrine’s entrance describes the area as「寂れている」.

田山花袋(大正5)『時は過ぎゆく』東京:新潮社, 196.

「と、ある日のことであつた。それは丁度雨あがりのくつきりと晴れた日で、今日摘まなければ芽が延びすぎるといふので、おかねは、朝飯をすますと、裏の雨戶の錠を下して、籠を抱へて、髪を手拭で蔽って そして梅の林の下にある茶畑へと行った。茶の葉はまだ雨のしめりを持つて、心持ちよく緑に延びていた。 朝日は緑葉を漉してさやかにあたりに照つた。」

ibid, 195

「七萬坪からある廣い地面、その三つ一は、良太の長年の骨折で、立派な茶畑になつて、その緑の間には赤い棒や髪を包んだ白い手拭などが到る處に隠見した。茶摘唄なども彼方此方にきこえた。」

Some sources mention that there were several falls, but a detailed article in the August 13, 1890 (Meiji 23) issue of Asahi Shimbun specifically mentions there were falls at two locations:「瀧は熊野十二所権現の境内に二ヶ所ありて春秋とも其の水の涸るることなく水源は江の頭なりという同境内は古松老杉鬱蒼として枝を交え午天もその日の影を漏らさず涼氣の起こる處一面の大池あり。」 I have found images and specific mentions of only two waterfalls: Ōtaki (大瀧, Great Falls) also known as Hagi no Taki (萩の滝, Bush Clover Falls), and Kogane Taki (黄金滝, Golden Falls). The latter consisted of two pipes protruding from the hillside and would not be considered a waterfall today.

Compiled from Travel Notes (遊歴雑記) by Jupponan Keijun (十方庵敬順), Shinjuku-kushi (新宿区史) published by Shinjuku-ku in 1955 (pp 321), Seidan Jūniso (政談十二社) by Kyoka Izumi (泉鏡花), contemporary newspapers, and other sources.

This description was engraved on the Jūnisō stone monument (十二社の碑) in 1851 (Kaei 4). It stands at the entrance of Kumano Shrine. 十二社碑. Retrieved on 2024-06-28.

Thank you, Glennis!

I think that even most Japanese have never heard of the pond although there are lots of Japanese language articles about it online. In English there is very little information.

When done, this article will be the most informative one about Jūnisō in any language. Not a boast, just a statement of fact 😊

So glad to read that you like the maps ❤️

I put even more effort into the selection and creation of maps than usual this time. I spent several days just on researching, thinking up, and creating the map with the tea fields and the modern buildings transposed on top.

Many more in the upcoming articles!

What an amazing transformation. I did not know anything about the Juniso pond. Loved the maps to situate myself to this history.

Looking forward to the development story under Ieyasu.