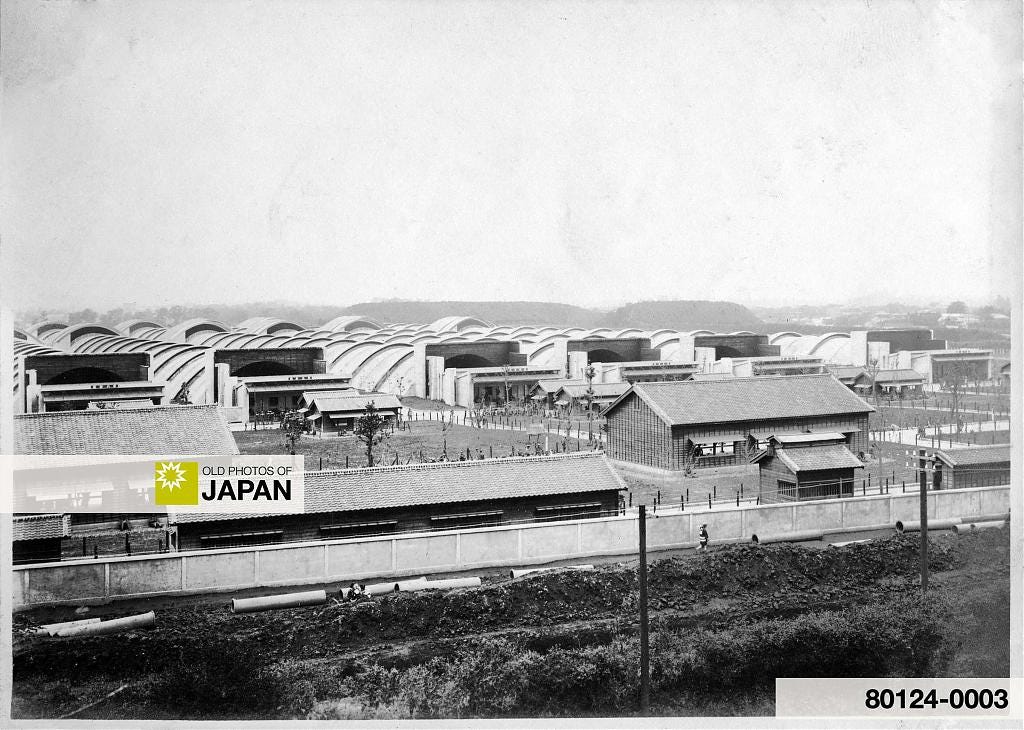

1944 • Shinjuku's Lost Paradise (7)

Jūnisō's geisha district becomes a great success, but militarism interferes…

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This is Part 7 of an essay about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

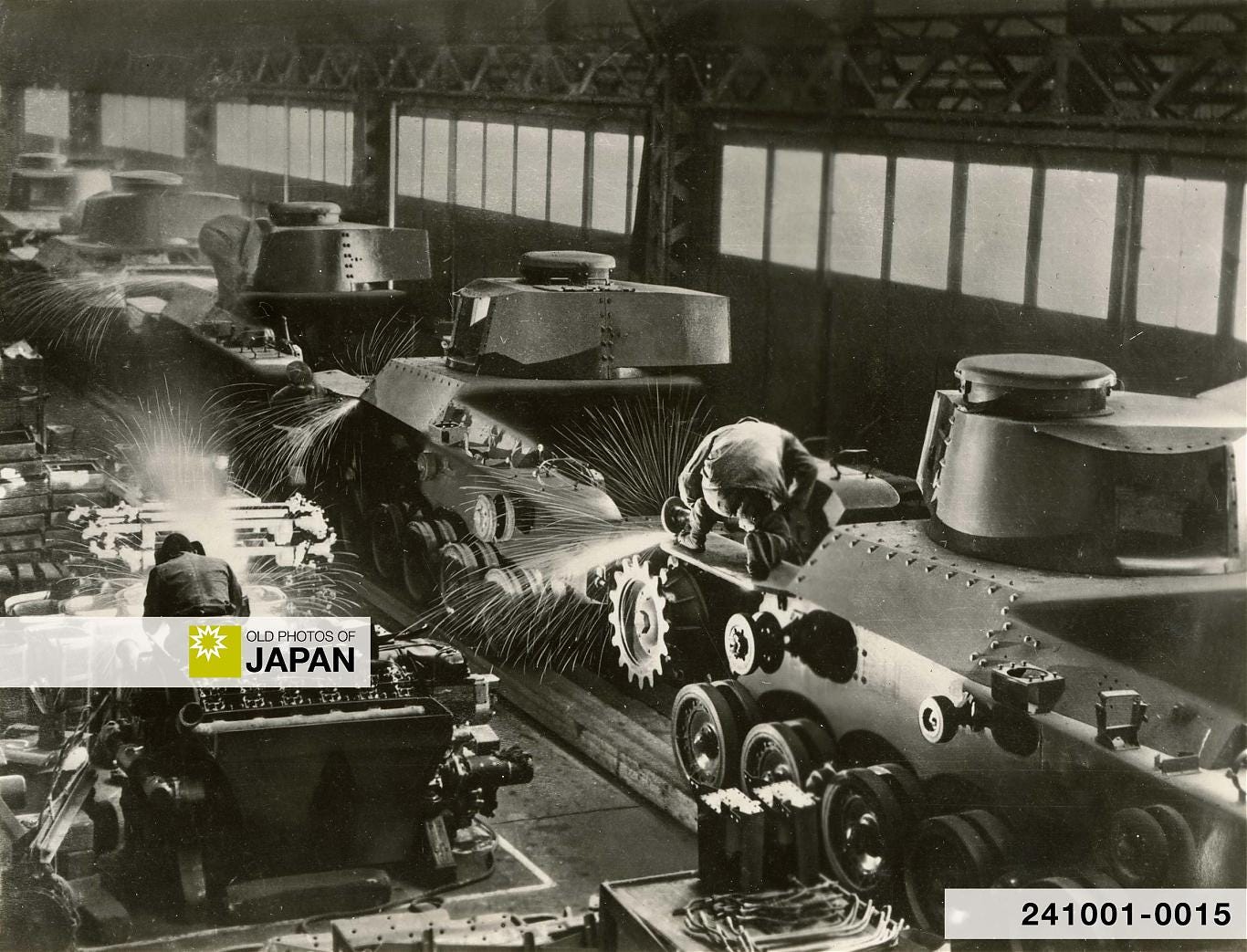

Tank production at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in 1944. Japanese militarism of the 1930s and 1940s initially benefited geisha districts like Jūnisō’s. But in the end it blasted most into oblivion.

Nature to Nightlife

Jūnisō Pond becoming an official hanamachi (geisha district) in 1924 (Taisho 13) spelled the end of its role as a natural retreat. Restaurants and machiai sprung up like mushrooms.

There was however little entrepreneurial spirit and by 1930 the place looked a bit sad. This changed after the entry of architect and entrepreneur Shinjirō Ikeda (池田伸治郎, 1897–?). From 1932 on Ikeda used the profits from a successful neon sign business to open several large restaurants in the area.1

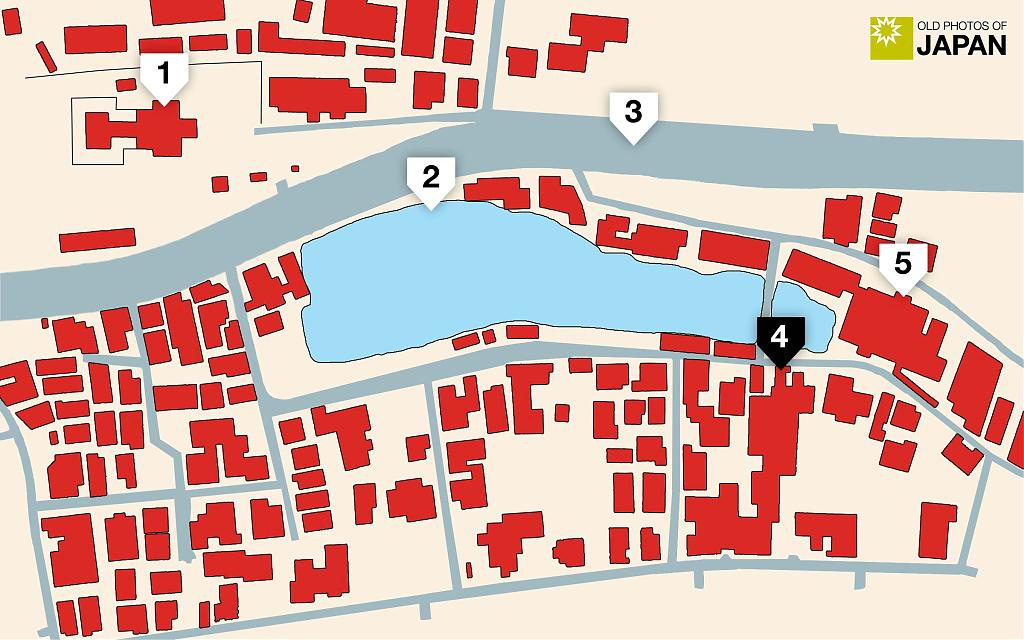

Simultaneously, modern infrastructure was developed. Around 1934, a new road (number 3 on the map below) separated the pond from the shrine. While visitor numbers soared, the pond slowly shrunk. Jūnisō’s once venerated ancient trees were cut down one after the other.

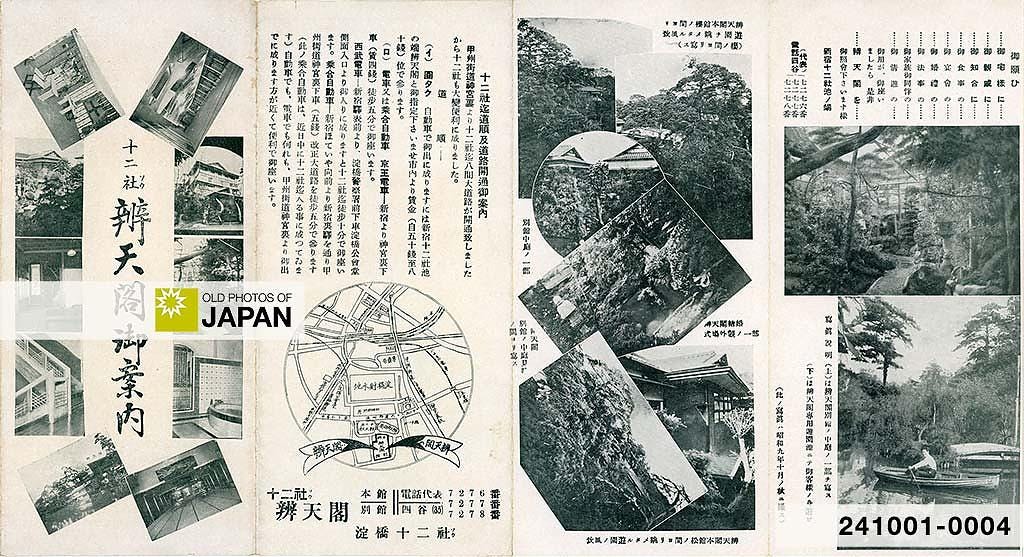

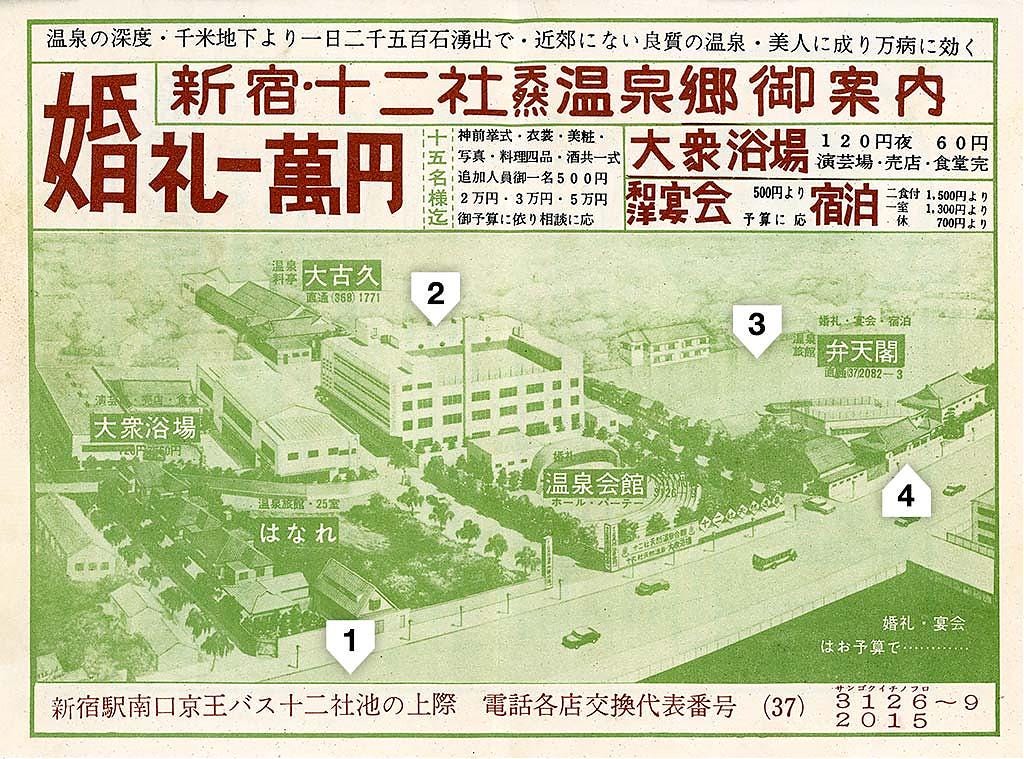

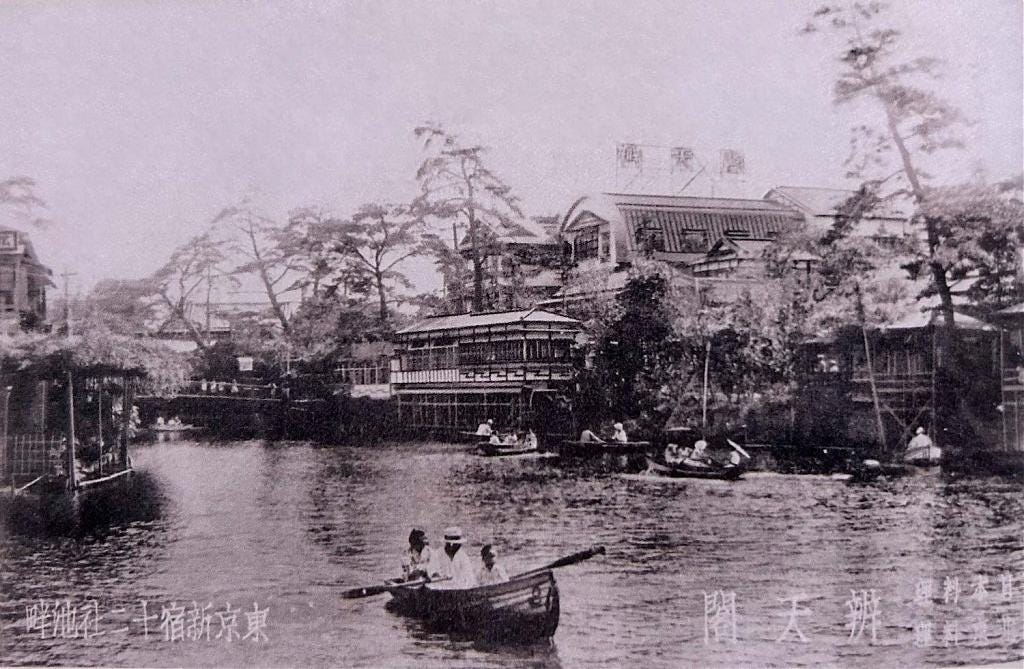

At the height of Jūnisō’s popularity there were nearly 100 restaurants and machiai, and some 300 geisha.2 Particularly prominent were Ikeda’s restaurants Ryūgūden (龍宮殿, number 5 on the map) and Bentenkaku (辨天閣, number 4).

Bentenkaku was remarkably ambitious. A 1934 (Showa 9) pamphlet boasted that its two buildings were “the finest in the city.” Built in “modern Kyoto-style” they covered an impressive 700 tsubo (approximately 2,310 square meters or 24,865 square feet).

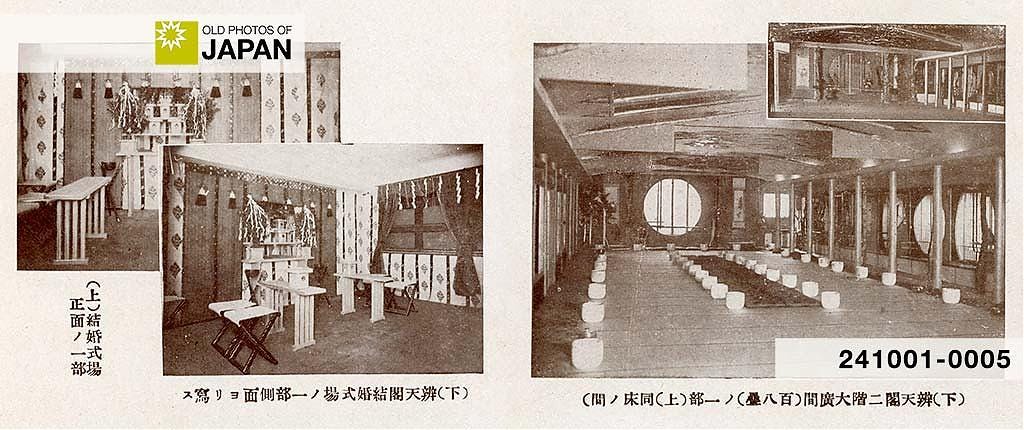

The three-story main building featured two spacious halls of 108 tatami mats each (about 178 square meters or 1916 square feet), as well as “various other large and small rooms.” The two-story annex counted 50 rooms “in a very tranquil setting.”

There were facilities for business meetings, banquets, funerals, and weddings—including a shrine for Shinto weddings. Bentenkaku offered both Japanese and Chinese cuisine, including luxurious crab dishes. It even had Western and Japanese-style hot spring baths on the premises.

The area had become an elegant center of nightlife, markedly different from the sleazy spot described by Sunday magazine when it bashed Jūnisō in 1912 (Meiji 45).

A 1938 (Showa 13) publication called Jūnisō “Yamanote’s Shinbashi.”3 Yamanote traditionally referred to the upper-class area west of the Imperial Palace. Shinbashi was Tokyo’s premier geisha district located near Ginza, frequented by government officials, famous actors and authors, and Japan’s top businessmen. At its peak it counted some 400 geisha, including some of Japan’s most famous.

War and Peace

As Japan militarized during the 1930s, Jūnisō’s newly designated geisha district appears to have benefited. Japan’s growing military budget revived the economy, while also producing growing numbers of potential clients.

In 1930 (Showa 5), the year before Japanese aggression in China began with the invasion of Manchuria, the Imperial Japanese Army consisted of 223,000 officers and men. By the end of WWII in 1945 (Showa 20) it counted 5.5 million soldiers, almost 25 times as many.4

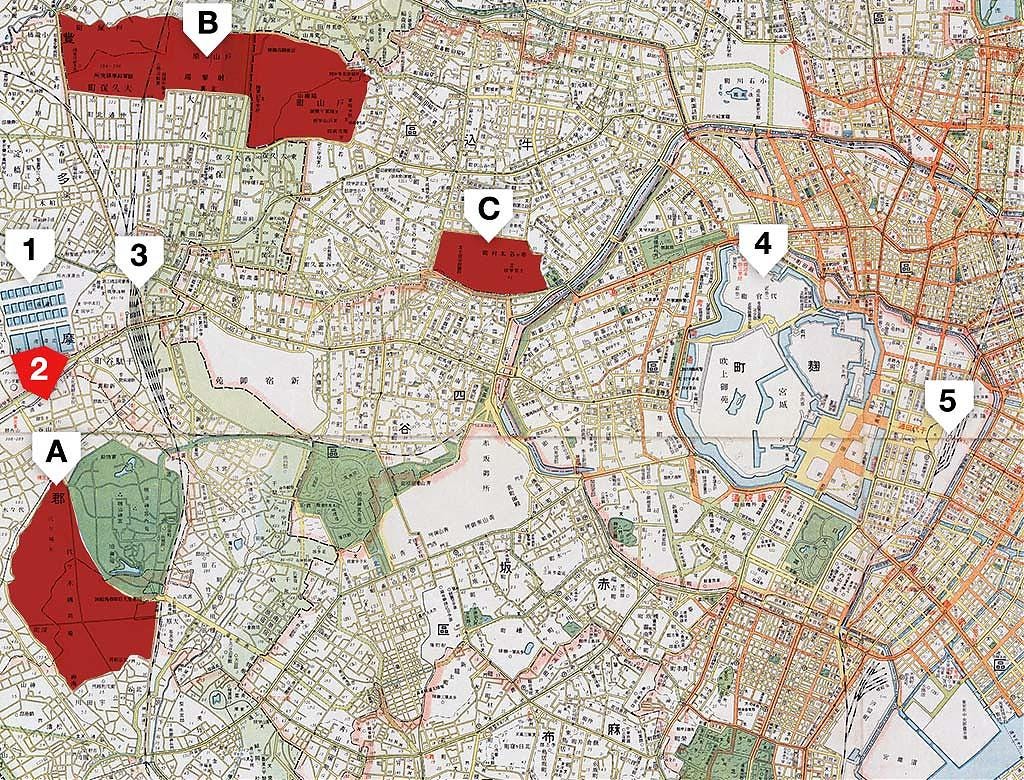

As it happens, Jūnisō was conveniently close to major military institutions. A mere three kilometers away was the Toyama Firing Range. Its state-of-the-art facilities were considered to be the largest in Asia. The area also hosted the Toyama Army Academy and the important Army Scientific Research Institute.

The Imperial Japanese Army Academy in Ichigaya was also nearby, as well as the Yoyogi Army Parade Ground. Unsurprisingly, military officers are said to have been common guests of Jūnisō’s geisha.

War may have benefited Jūnisō during the 1930s, it also brought the newly minted geisha district to its knees.

In 1944 (Showa 19) the government ordered all restaurants, teahouses, geisha houses, cafes, and bars to close for business. Many geisha ended up working at weapon factories. The final blow came in April and May of 1945 when U.S. carpet bombing almost completely flattened Yodobashi. Only Jūnisō Kumano Shrine somehow miraculously survived.

But Jūnisō was not yet ready to die. After the war the hanamachi was rebuilt on a smaller scale. When the Korean War (1950–1953) reignited Japan’s economy, the entertainment district once again flourished. This culminated in 1958 (Showa 33) when Bentenkaku excavated a hot spring and opened it as Jūnisō Onsen.

A print ad for Jūnisō Onsen from 1959 (Showa 34) still shows the pond, but it is just a grey area. It is not even mentioned in the text. The sad polluted remnants of Jūnisō Pond—in 1941 the pond’s carps had died because of pollution—no longer played a role in attracting people to the area.

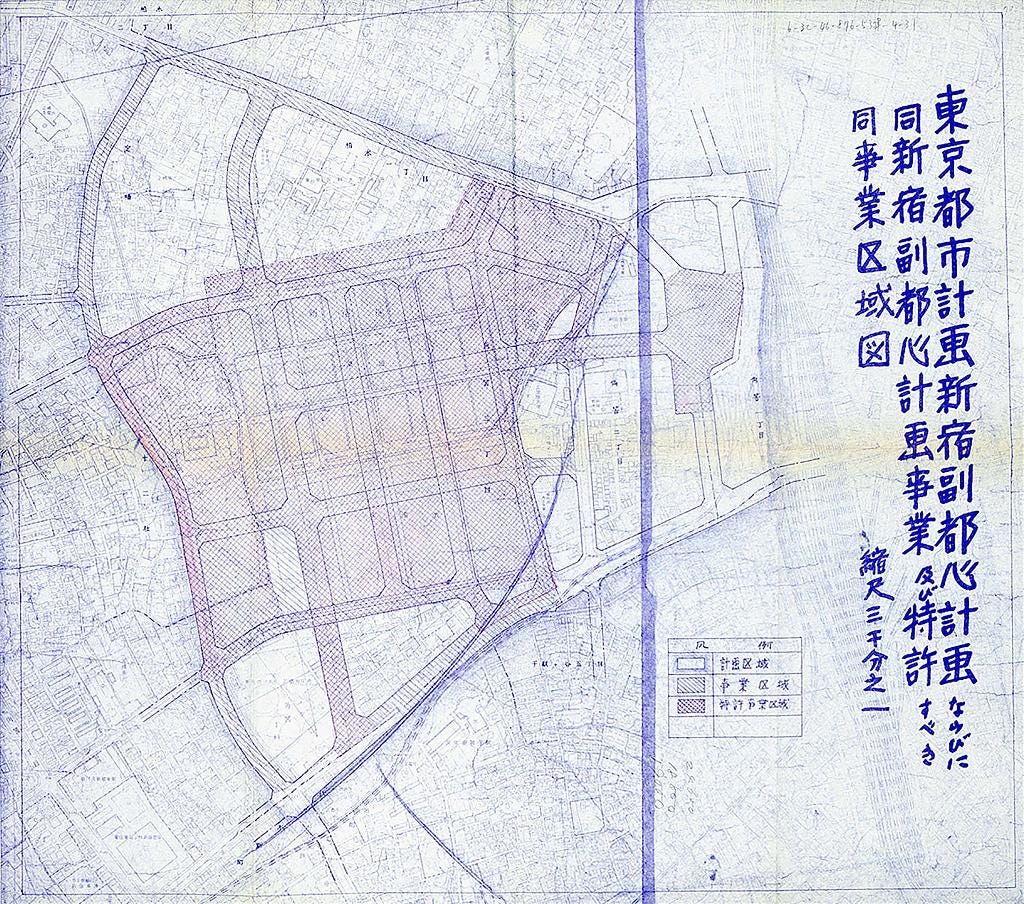

The 1950s were Jūnisō’s last hurrah. In 1960 (Showa 35) Tokyo decided to close the Yodobashi Water Purification Plant and redevelop the area located west of Jūnisō as a skyscraper district with a large public park. The project, known as the Shinjuku Subcenter Plan (新宿副都心計画, Shinjuku fukutoshin keikaku), launched a revolutionary change in urban development planning in Japan.5

The purification plant closed in 1965 (Showa 40). Three years later, Shinjuku Central Park (新宿中央公園, Shinjuku Chūō Kōen) was opened on part of its former location. In the same year, the little that was left of Jūnisō Pond was filled in.

Nishi-Shinjuku’s very first skyscraper, the Keio Plaza Hotel, was completed in 1971 (Showa 46). Many others followed until the giant Tokyo Metropolitan Government Buildings were completed on the last empty space in 1990 (Heisei 2).

The last vestiges of Jūnisō’s geisha district vanished almost unnoticed in the mid-1980s when most surviving restaurants went out of business. Jūnisō Onsen, now a small affair in the basement of an apartment building, closed in 2009 (Heisei 21). News media did not even bother mentioning it.

Today, the only remains of Jūnisō’s past are the shrine and the names of bus stops.

Sole Survivor

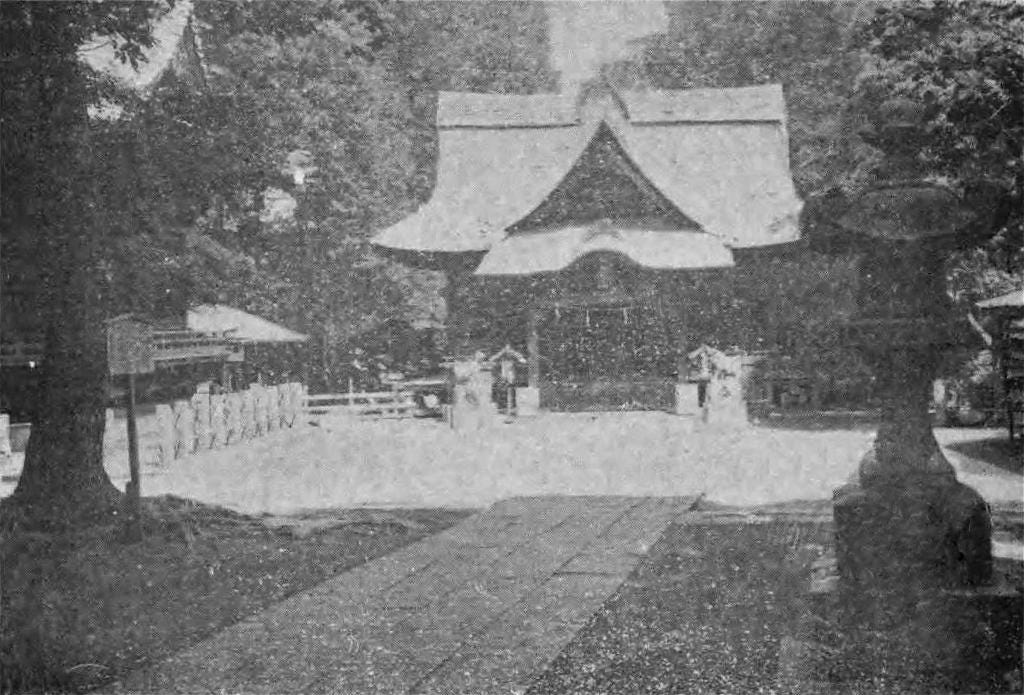

While Jūnisō Pond fell prey to the upheavals of the 20th century, Jūnisō Kumano Shrine somehow survived.6 The thatched shrine building photographed by famed Italian photographer Felice Beato in the 1860s and described in the influential guidebook A Handbook for Travellers in Japan, even survived the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 (Taisho 12).7

A history book published in 1931 (Showa 6) still showed a photo of the original thatched shrine building. Photographed in 1926 (Taisho 15) it had barely changed since the 1860s. The caption mentioned that it was being rebuilt.8

The reconstruction arose from transformative city planning following in the wake of the terrifying fires kindled by the 1923 quake. By 1934 (Showa 9) the shrine grounds had been drastically modified and the shrine moved and rebuilt with used timber received from recently renovated Meiji Shrine. Sadly, Jūnisō Shrine’s stunning thatched roof vanished, the new roof featured tiles.

During World War II nearby Meiji Shrine was destroyed by American fire bombing, but Jūnisō Shrine once again survived. The 1934 shrine building stands to this day, humble witness of a storied but mostly forgotten past.

Although nothing remains of Jūnisō Pond, one could argue that Shinjuku Central Park fulfills the original functions of Jūnisō Pond in modern form. There is no large pond, but on the park’s edge stand the contemporary equivalents of the traditional teahouse, a casual restaurant and a Starbucks coffee shop.

The park even has a man-made waterfall. In contrast with Jūnisō’s waterfall, this one exaggerates and even glorifies its artificiality.

Click on the link below to see a Google Map of Shinjuku Jūnisō Kumano Shrine’s current location, next to Shinjuku Central Park.

★ Visual Chronology

This essay features a large number of rare images of Nishi-Shinjuku’s Jūnisō Pond, many of them previously unknown. I have created a visual chronology using these and other images for a clear overview of how the pond changed between the 1860s and 1930s. Maps display the viewpoints of these images.

About the Top Photo

This may have been taken at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries’ Sagamihara Machinery Works in Kanagawa Prefecture. In 1938 (Showa 13) the Imperial Japanese Army designated it as a production facility specializing in tanks. The tanks are believed to be the Type 1 Chi-He medium tank.

Alternative Spellings

十二社︀ (Jūnisō, kyūjitai)

十二叟 (Jūnisō)

十二所 (Jūnisō)

Djunisso (French)

Dzû-ni-so (German)

Džu-ni-so (German)

Jionizo (French)

Jiū-ni-sō (English)

Junisso (French, German)

Acknowledgements

This research would have been impossible without the generous assistance and input of (in alphabetical order) Kaoru Baba (馬場郁) of Bibliothèque d’études japonaises, Sebastian Dobson (セバスチャン・ドブソン), Naomi Haga (芳賀直美), Atsuko Hirano (平野敦子), the Kreitmann family (クレットマン家), Akita Miyazawa (宮沢聡) of the Shinjuku Historical Museum (新宿歴史博物館), Chiaki Moteki (茂木千亜紀), Christian Polak (クリスチャン・ポラック), Naoyuki Shinagawa (品川尚之), Bruno Tartarin (ブルーノ・タルタラン) of Photovintagefrance, Yuki Yamato (大和由紀子), as well as the staff of Kumano Jinja (熊野神社), the Nagasaki University Library (長崎大学附属図書館), the National Diet Library (国立国会図書館), Shinjuku Ward Chūō Library (新宿区立中央図書館), the Tokyo Metropolitan Archives (東京都公文書館), and Tsunohazu Library (角筈図書館).

Notes

稻臣 等 (1938)『辨天閣・池田仲治郎・淀橋風淀橋十二社池峰』in『一業倶楽部会員総覧 第1編』一業倶楽部, 138.

新宿区生涯学習財団新宿歴史博物館学芸課 (2003)『新宿区の民俗 (6) 淀橋地区篇』新宿歴史博物館, 48.

稻臣 等 (1938)『辨天閣・池田仲治郎・淀橋風淀橋十二社池峰』in『一業倶楽部会員総覧 第1編』一業倶楽部, 138.

⻑野耕治; 植松孝司; 石丸安蔵 (2015).『日本軍の人的戦力整備について : 昭和初期の予備役制度を中心として』 防衛省防衛研究所 (National Institute for Defense Studies)『防衛研究所紀要』(NIDS Security Studies) 17(2), 137.

『新宿副都心の整備・東京の都市づくり政策』features interviews with people directly involved in the creation of the Shinjuku Subcenter Plan. Extremely informative.

Kumano Jūnisō Gongen (熊野十二所権現社) was renamed Kumano Jinja (熊野神社) in 1868 (Meiji 1) it is one of the protecting shrines of Shinjuku.

Kumano shrines enshrine deities of the Kumano region in Mie, Wakayama and Nara prefectures, in terms of religion one of the oldest and most significant areas of Japan. Kumano shrines fused Buddhism and Shinto, an influential practice known as shinbutsu-shūgō. Although the new Meiji government separated Shinto from Buddhism in 1868 (Meiji 1), Japan still counts over 3,000 Kumano shrines today.

See SHINJUKU’S LOST PARADISE (3), near the bottom of the article, for a description in the 1881 edition. The 1913 edition’s description of Jūnisō shrine is much shorter, but still mentions the thatched roof:

“Jūnisō. Tram to Shinjiku whence a short walk or ride. Crossing the railway, the extensive buildings seen are those of the waterworks for the supply of Tokyo. The road to Jūnisō turns off by the further side of these works, and in 10 min. comes to the small thatched temple of Jūnisō Gongen, dedicated to the gods of Kumano. Below the temple lies a large pond, plentifully stocked with a species of carp, and surrounded by tea-sheds and tea-houses. Jūnisō is a favourite spot for picnic parties in the warmer months.”

Chamberlain, Basil Hall; Mason, W. B. (1913). Murray’s Handbook Japan: A handbook for travellers in Japan, including Formosa. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 139.

加藤盛慶 (1931). 『東京淀橋誌考』武蔵郷土史料学会, 12th photo page between pages 376–377.

Bravo - Yayogi Park was a former parade ground, wow!

The rate of change is astounding and now marked by scattered bus stop names.

Need to visit the miraculously surviving shrine.

Wow! Geishas working in munitions factories was not something I expected.

The amount of time and effort into detailing the history of this lost paradise is not at all lost on me.

Thank you for the lesson and all those photographs!

When I visit Shinjuku next, I will have another perspective.