Tokyo, 1860 • Shinjuku's Lost Paradise (3)

A pond lost to history tells Tokyo’s story…

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This is Part 3 of an essay about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

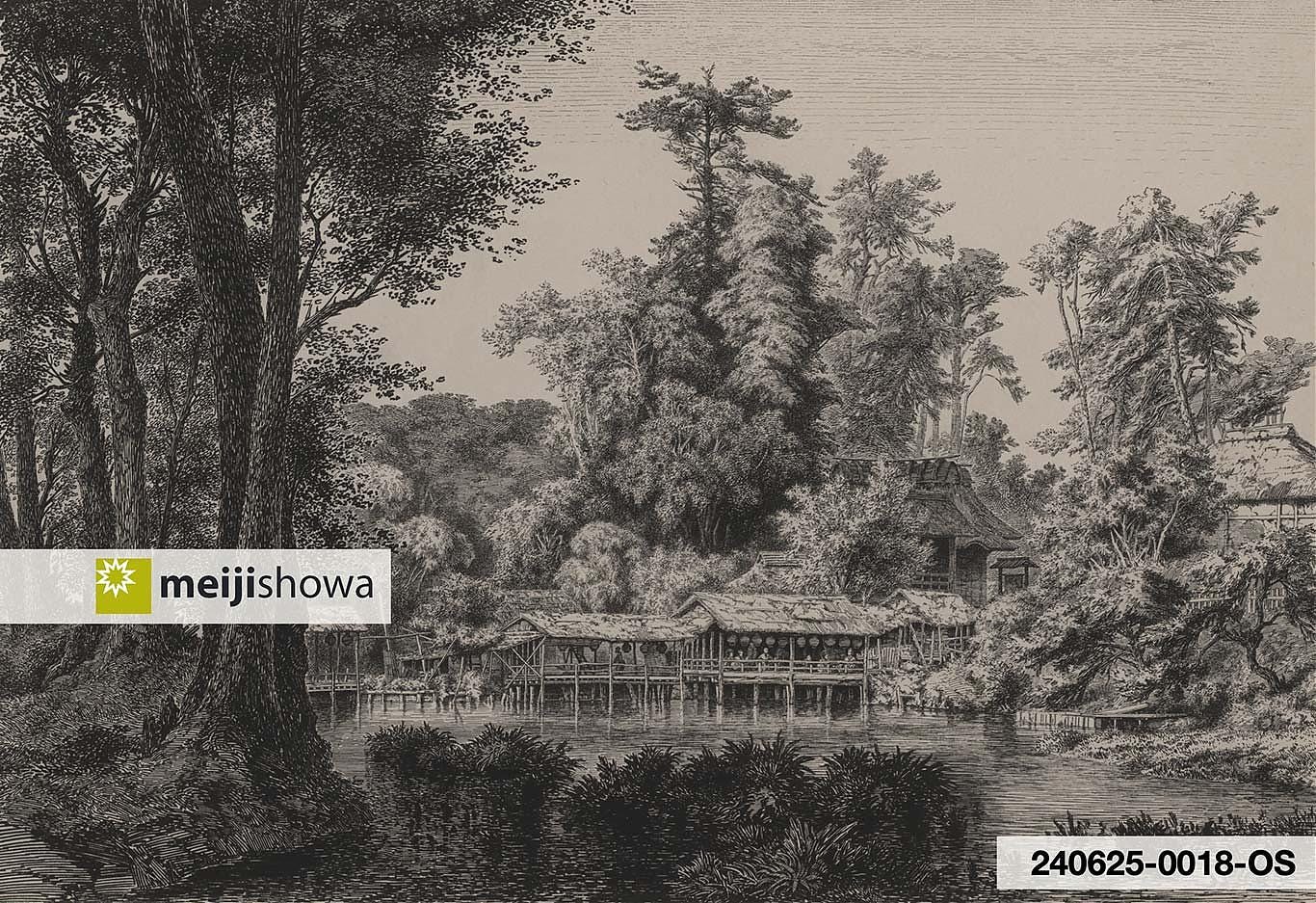

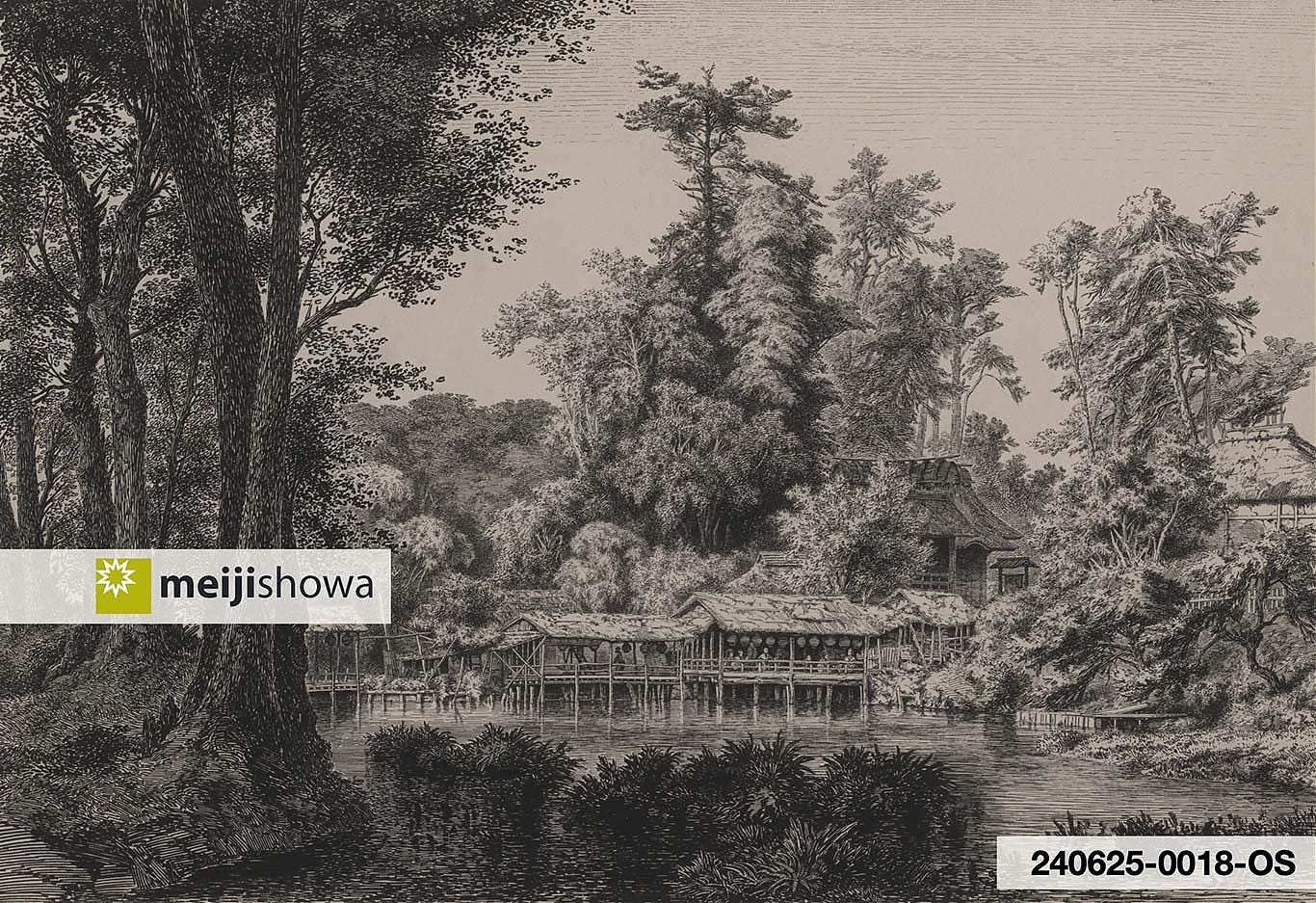

This print is the first known foreign depiction of Jūnisō. Thanks to foreigners—visiting after Japan opened its borders in 1859—we have detailed accounts of Jūnisō, describing aspects that locals took for granted.

On July 4, 1859 (Ansei 6) Yokohama was opened to foreign trade, ending Japan’s two centuries of isolation. Foreigners were not free to go anywhere, though. Yokohama’s foreign residents were restricted to a limited area around the city and were not allowed to cross the Tamagawa River. This effectively blocked them from visiting Edo and Jūnisō.

However, every major development in Tokyo always touched Jūnisō. This was true for the opening of Japan’s borders as well. Though Edo was off-limits to foreigners, diplomats and oyatoi gaikokujin (foreign advisors employed by the Japanese government) were allowed to enter, and stay.

It didn’t take long before their Japanese minders took them to Jūnisō, which soon became a popular destination for foreign visitors. They left valuable descriptions of Jūnisō, telling us what the area looked like just before Japan modernized.

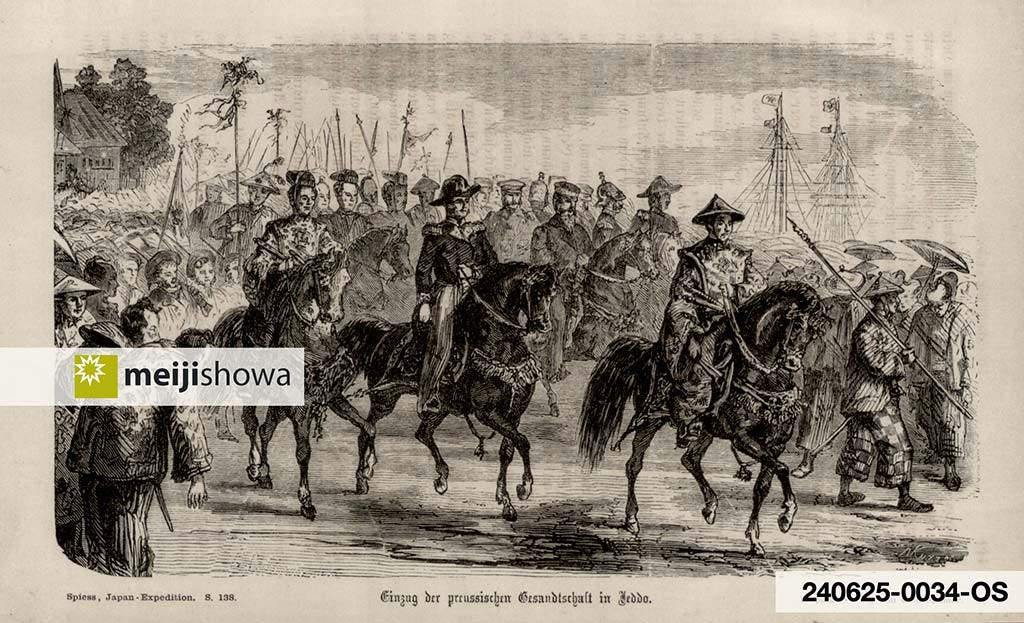

One of these visitors was the Prussian diplomat Count Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg (1815–1881) who visited Japan from 1860 through 1861 (Man’en 1–2) to negotiate a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with Japan.

Eulenburg first visited Jūnisō on October 24, 1860. He described it as “a very nicely situated teahouse with a waterfall, beautiful vegetation, etc.”1 The count clearly liked Jūnisō—less than three weeks later he held a large picnic here and invited the British delegation.

It was a big affair featuring a concert by the naval band of the Prussian steamer corvette Arkona, likely the first performance of Western music in Shinjuku.2

After an hour’s ride through beautiful trees and hedges and past pretty little houses, we arrived in Junisso. There we found a nicely laid table outside, as I had sent the cook, men and dishes ahead. Our naval band welcomed us with the English national anthem. Breakfast tasted splendid after the ride and in the warm sun.

Hundreds of people who had rushed from the neighborhood surrounded us at a respectful distance, as the mayor had indicated how far they could advance by string that he had tied to trees. This slight barrier was enough to hold them back.

My young men drank heartily, and when we got up from the table they called the priests of the neighboring temple and gave them so much to drink that the poor men got quite queasy.

We took a nice walk through the still uncut rice fields and then got back on our horses to return to the city by a different route.

Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg (November 10, 1860)

The “well-known cheerful melodies sounded more beautiful in this environment than ever before,” noted German-American artist Wilhelm Heine (1827–1885) in his diary.3 The hundreds of curious locals apparently also enjoyed the music:4

Probably for the first time, the drums and trumpets of European military marches rang out in the old grove of the Twelve Gods Temple. But they caused no offense, the merriment was general and hardly greater among the feasting party than among the watching Japanese.

Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien (November 10, 1860)

The picnic had an unexpected consequence. The day after, the sobered up priests of the shrine showed up at the Prussian delegation:5

The next day the priests of Džu-ni-so appeared in Akabane to inform the envoy that the breakfast had taken place on their property; moreover, three daimyos [feudal lords] had wanted to visit the temple at the same time, but were deterred by the presence of the foreigners. The count gladly granted them the compensation they requested, and they departed satisfied.

Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien (November 10, 1860)

The priests may not have been too happy about the mission’s visit, but thanks to the Prussians we have an extremely detailed description of Jūnisō in 1860:6

We therefore directed our ride towards the western surroundings on this day and were led by the Yakunins who accompanied us to a distant Shinto temple, which even Heusken, who was familiar with the region, did not know about.

The route offers a series of the most charming landscapes; one passes through village-like suburbs, whose population streamed in in bright crowds, then lush valleys, shady groves and sunken paths. At one point friendly country houses and farmsteads peek invitingly over green garden hedges, then gloomy fences line the path, overlooked by the hundred-year-old treetops of elegant parks.

The Temple of the Twelve Gods, Džu-ni-so, lies on a hillside shaded by slender firs and pines, between two streams. The upper one roars in foaming cascades through the rocky banks, the other is artificially dammed up to form a pond near the temple, and from there flows clear and rippling in gentle curves through the dark forest of the hollow, to join its impetuous brother further down. Moss-covered rocky debris and thick grass cover the slopes, and from the heights on the other side one looks out over a green, peaceful farmland.

The temple is built unpretentiously but elegantly from wood, the roof from straw and reeds. But one should not imagine the Japanese thatched roof to be anything like our German ones. It has architectural forms, especially in the temples, is held together at the ridge by wooden trestles between which bamboo canes run, and is so neatly and artificially trimmed that from a distance it looks as if it had been cast or planed.

At the temple of Džu-ni-so, the pointed front gable projects in a curved line over the entrance, forming a hall supported by pillars; the panels and beam heads are carved. The chapel behind the temple is a latticed shrine without an entrance, also with a gracefully curved thatched roof. A broad avenue of pine trees with a wooden torii meets the main façade of the sanctuary, to which entrance steps lead; stone monsters — Korean dogs — and bronze water buckets stand on either side of it.

Next to the temple is a very rustic teahouse, and from the artificial dam, pavilions made of wood and thatch have been built out into the pond, where the guests sit down for a cheerful feast and delight in feeding the large golden carp. From afar one can hear the rushing cascade of the upper brook. This is said to be used by lively drinkers who have heated up their senses by writing poems at a party. To refresh their bewildered senses they stick their heavy heads under the cold eaves in order to sober up as quickly as possible and become capable of new pleasures. Džu-ni-so is considered a meeting place for urban aesthetes; the location is extremely lovely and well suited to provoking poetic outpourings.

The way back led us down the cool hollow; bright rays of sunlight, breaking through the green darkness, played on the mossy banks of the stream, which flows murmuring quietly and contentedly through the lovely wilderness. Below, a gate opens onto the open field. Turning west, in a few minutes you reach a busy urban street that leads endlessly to the central parts of Yeddo [Edo].

The forest solitude of the kami shrine gives no indication of the proximity of a noisy town district; one finds oneself strangely surprised.

Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien (October 24, 1860)

Another prominent foreigner who left us invaluable documentation—from 1867 (Keiō 3)—was French military advisor Jules Brunet (1838–1911). His extraordinary experience in Japan inspired the 2003 movie The Last Samurai, featuring actors Tom Cruise and Ken Watanabe.

Brunet, who was an accomplished artist, created two sketches of Jūnisō, one of which was shared in PART 2. It shows the “eaves” described in the above quote. His panoramic view below shows the same corner of the pond as in the Prussian view above, but from the right of the Prussian image—Brunet had his back towards the shrine. The teahouses had clearly been renewed.

A Peaceful Place

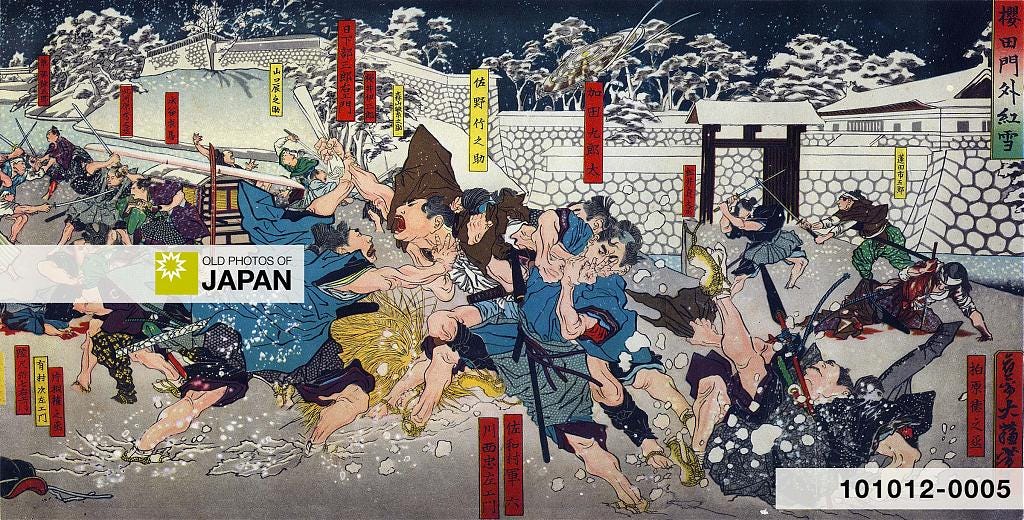

Notable about the foreign accounts of Jūnisō is that they all describe a peaceful place. However, after its borders were opened, Japan was far from peaceful. Many foreigners and Japanese officials were murdered by disaffected samurai under the rallying cry “Revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians” (尊皇攘夷, sonnō jōi).

In August 1859, two Russians were murdered on the street in Yokohama. Five months later, in January, the Japanese interpreter of British diplomat John Rutherford Alcock (1809–1897) was stabbed to death at the English legation in Edo. Only a few days later the French legation in Edo burned down by arson.

In February 1860, two Dutch captains were slaughtered on the main street of Yokohama. The following March, Ii Naosuke (井伊直弼, 1815–1860), the Chief Minister of the Tokugawa shogunate who espoused cooperation with foreign nations, was assassinated in front of Edo Castle. More attacks followed.7

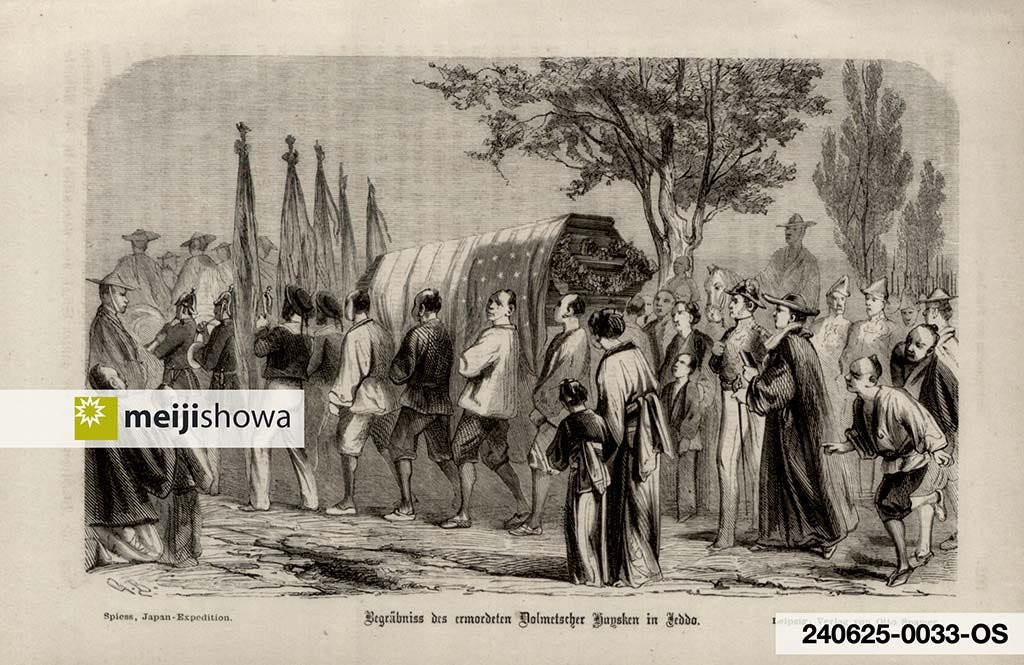

The greatest shock came when Henry Heusken (1832–1861) was ambushed in Edo. Heusken was the Dutch-American interpreter for the first American consulate in Japan and played a major role in the negotiations to open commercial relations between the two countries.

Heusken was loaned to the Prussian mission and is even mentioned in the Prussian account of Jūnisō above, suggesting that he visited Jūnisō less than three months before his murder. He was killed while riding home after dinner with Eulenburg.

In short, this was a time of great danger. Many foreigners would not leave their home without a weapon. Japanese who were in favor of opening Japan’s borders and learning from the West kept a low profile. Even popular Japanese educator Yukichi Fukuzawa (福澤 諭吉, 1835–1901) stayed at home after dark and used fake names while traveling:8

The period from the Bunkyu era to the sixth or seventh year of Meiji—some twelve or thirteen years—was for me the most dangerous. I never ventured out of my house in the evenings during that period. When obliged to travel, I went under an assumed name, not daring to put my real name even on my baggage. I seemed continually like a man eloping under cover or a thief escaping detection.

The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa

Eulenburg was very much aware of the danger. On the day of his first visit to Jūnisō he wrote the following account in a letter home:9

I visited the English envoy and rode to him by the shortest route, i.e. through the suburb of Shinagawa. But I met so many drunken daimio officers on foot and on horseback that I felt quite uneasy.

The fellows either ride straight towards you or stop when they meet you. If they are good-natured, they laugh at you and mock you; if they are malicious, they look at you with grim eyes and grab their swords. Imagine a city in which at least 100,000 people (some say 300,000) are always armed with two razor-sharp swords.

The police are completely powerless, they only observe and do not intervene. The Yakunins [officials] who accompany us stay behind as soon as we approach a situation that could turn unpleasant. So you have to rely entirely on yourself, and I will start arming my men with revolvers.

Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg (October 24, 1860)

Yet, Eulenburg and Rutherford Alcock—as prominent diplomats prime targets for assassination—considered Jūnisō safe enough for a picnic in the open. They clearly felt so safe at Jūnisō that they had no qualms about playing loud military marches that drew hundreds of onlookers from the surroundings.

This truly reveals Jūnisō’s secluded and peaceful atmosphere. In 1851, Buddhist monk Fukyū wrote that at Jūnisō “one feels as if one has arrived in the land of Buddha.” A decade later, foreigners apparently felt this even when in danger.

Globetrotters

After the Meiji Restoration of 1868 (Meiji 1), peace slowly returned and in 1874 (Meiji 7) the new Meiji government considered it safe enough to open all of Japan to foreign travelers.10 Coincidentally, global tourism emerged during this time; Jūnisō now appeared on the itinerary of globetrotters.

In 1881 (Meiji 14) the trailblazing Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan, partly written by British diplomat and acclaimed Japanologist Sir Ernest Mason Satow (1843-1929), introduced Jūnisō to this new market.

Satow had first visited Jūnisō in 1862 (Bunkyū 2) as a young interpreter at the British legation, and knew it well.11 Thanks to him we have a brief description of Jūnisō just before the onslaught of modernization changed it forever:12

For the first half hour the road follows the Ōme Kai-dō, and then turns off to the [left] through the fields for about 3/4 [miles], before reaching the square stone pillar which marks the path leading to Jiū-ni-Sō (more correctly called Jiu-ni-Sho Gon-gen), a small temple dedicated to the Twelve Gods of Kumano.

The temple buildings consist of an unpainted thatched structure in front, containing an ex-voto hall and an oratory, and of a chapel behind, which is slightly decorated with carvings of pines and peonies, while close by is a stage for the performance of the Kagura dances.

Below the temple lies a little lake picturesquely embosomed in trees, and lined at its upper end by a row of tea-sheds. It is a favourite resort during the warmer months and also at the end of autumn, when crowds of people from the city come out to enjoy the beautiful tints of the maple foliage.

Founded originally in 1403 by a native of Ki-shiu, it was restored in the beginning of the 18th century. The annual festival is held on the 21st of September. Carriages can only go as far as the point at which Ōme Kai-dō is quitted.

Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan (1881)

Modernization

Sadly, Jūnisō’s serenity did not last. The end of Japan’s centuries old isolationism set a train of momentous events in motion that dramatically transformed Japan. This transformation also touched Jūnisō.

Continue to Part 4 : Modernization arrives.

Related Articles

Read the articles below for more about the opening of Japan's borders (Nagasaki, 1865), the events it provoked in Japan (1863 Tokyo), and global tourism (Spotlight):

Notes

Zu Eulenburg, Friedrich Albrecht (1900). Ost-Asien 1860-1862 in Briefen des Grafen Fritz zu Eulenburg. Hrsg. von Graf Philipp zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld. Berlin: Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn, 98.

ibid, 106–107.

For more information about the mission, read The Prussian Expedition to Japan 1860/61.

Heine, Wilhelm (1864). Eine Weltreise um die nördliche Hemisphäre in Verbindung mit der Ostasiatischen Expedition 1860 und 1861. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 255.

Die preussische Expedition nach Ost-Asien: nach amtlichen Quellen, 1866. Zweiter Band. Berlin, Verlag der Königlichen Geheimen Ober-Hofbuchdruckerei (1866), 61.

ibid.

ibid, 39–40.

This is the only written account I have found so far that describes a waterway emerging from Jūnisō Pond itself. It is also not marked on any maps. Because it is an extremely detailed description I consider it reliable. Additionally, the chairman of the Nishi-Shinjuku 4-Chome Neighborhood Association (西新宿四丁目町会), Mr. Naoyuki Shinagawa (品川尚之, 1951), told me in an August 4, 2024 interview that elderly residents had described this waterway to him.

Duits, Kjeld. From Dejima to Tokyo: 3. Kanagawa-Yokohama. Retrieved on 2024-07-13.

Kiyooka, Aichi (1972). The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa. New York: Schocken Books, 228.

Zu Eulenburg, Friedrich Albrecht (1900). Ost-Asien 1860-1862 in Briefen des Grafen Fritz zu Eulenburg. Hrsg. von Graf Philipp zu Eulenburg-Hertefeld. Berlin: Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn, 97–98.

Rohe, Gregory L (2015). Travel Guides, Travelers and Guides: Meiji Period Globetrotters and the Visualization of Japan. The Journal of the Japan Association for Interpreting and Translation Studies, 2015, Volume 15, 79.

Satow, Ernest Mason; Hawes, A. G. S (1881). A Handbook for Travellers in Central & Northern Japan. Yokohama: Kelly & co., 47–48.

Satow, Ernest Mason (1921). A diplomat in Japan; the inner history of the critical years in the evolution of Japan when the ports were opened and the monarchy restored. London : Seeley, Service & Co. Limited, 66. | ブリュネ、岡田新一、など(1988). 『函館の幕末・維新: フランス士官ブリュネのスケッチ100枚』中央公論新社, 24.

Great series!

I linked to Part 1 in a Facebook group, so hopefully you’ll get a bit of traffic from there!

My paternal heritage is Prussian. I found this article really interesting!