Tokyo 1920s • Shinjuku's Lost Paradise (6)

Jūnisō becomes a geisha district, delighting some, enraging others…

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This is Part 6 of an essay about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

1920s Shinjuku. A railway and population explosion turned it into a thriving modern city. No longer rural and remote, Jūnisō now became a geisha district, delighting some, enraging others.

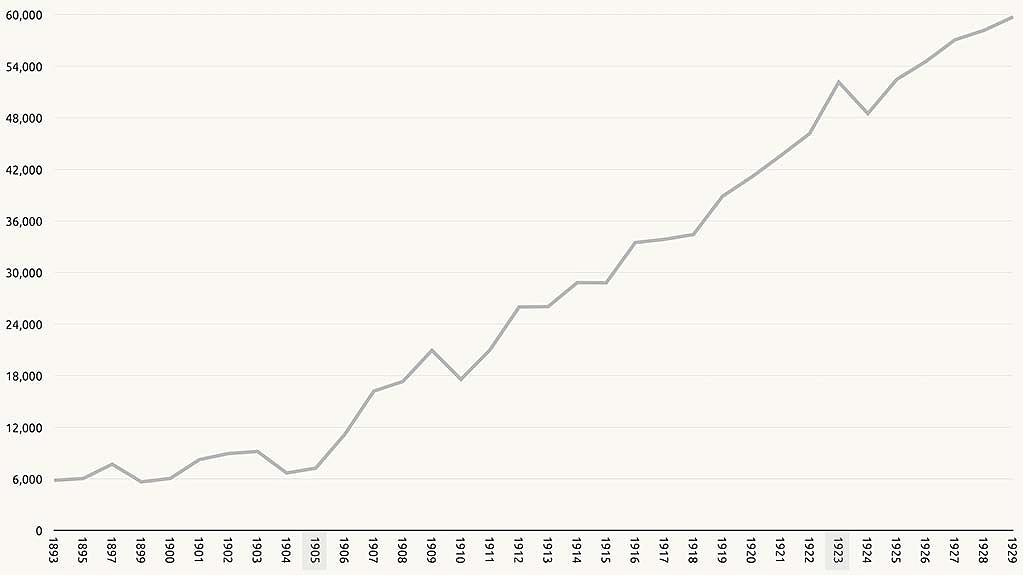

As late as 1909 (Meiji 42) Jūnisō was still a remote place with rice paddies. By the 1920s it was heavily urbanized. When construction of the water purification plant began in 1893 (Meiji 26) Yodobashi (now Nishi-Shinjuku) counted 6,000 residents. By 1929 (Showa 4) that number had surged tenfold to 60,000.1 For comparison, Nishi-Shinjuku had about 22,400 residents in 2023.

The common narrative is that the population of Nishi-Shinjuku surged after the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 (Taisho 12) because many survivors relocated to the more stable terrain of Western Tokyo.

Yodobashi’s population figures however tell a different story. Look at the graph below. There is indeed a bump in 1923. But it is preceded by 18 years of steady and strong population growth that started after the end of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 (Meiji 38). The growth after 1923 is a continuation of this trend.

The trend line is so consistent that it aligns almost perfectly with a ruler—1923 is just a brief spike. Notably, it corrected itself the year after.2

Railway Hub

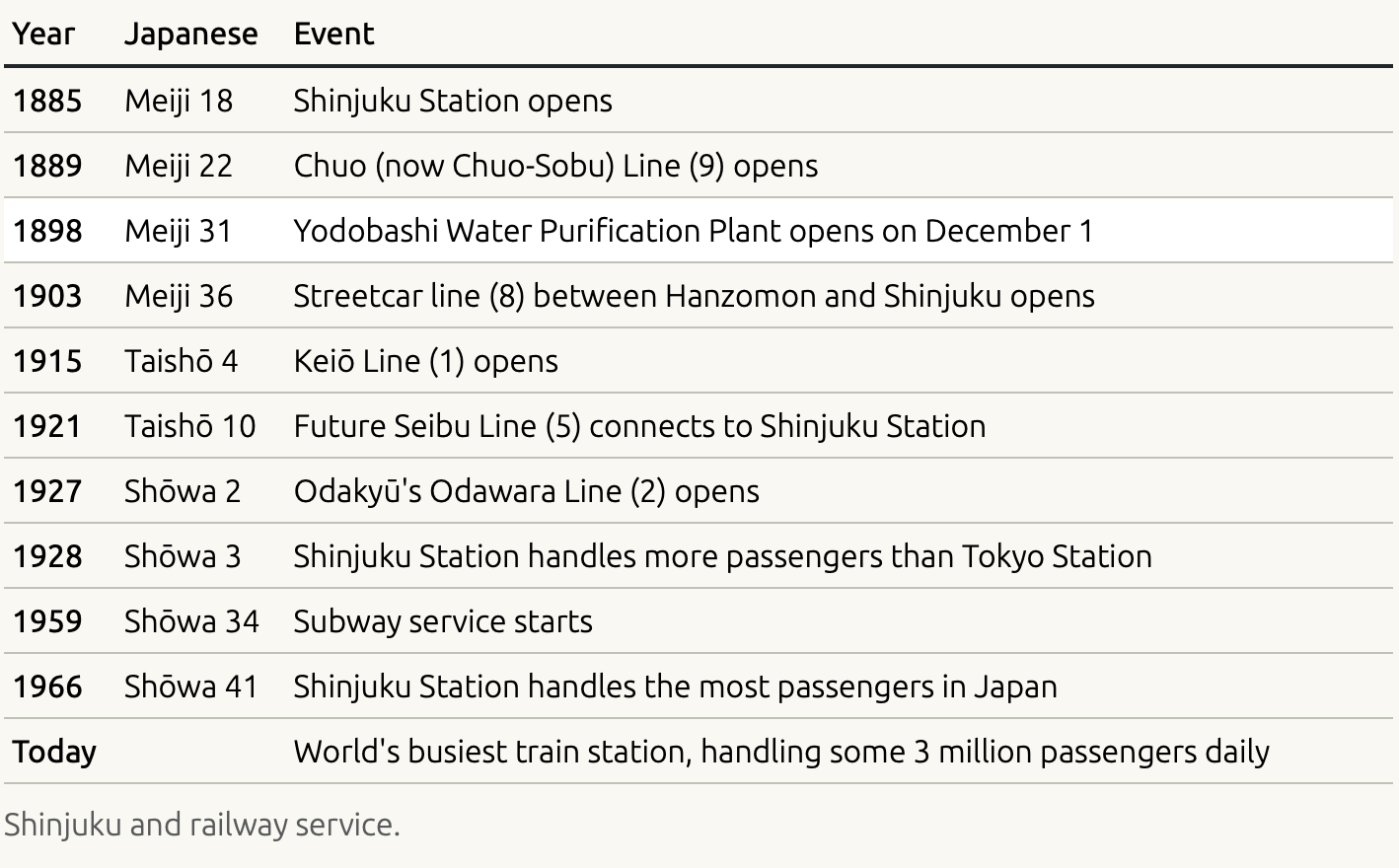

Yodobashi’s astounding population growth, and the commercialization of Jūnisō, was partly the result of railways connecting to Shinjuku.

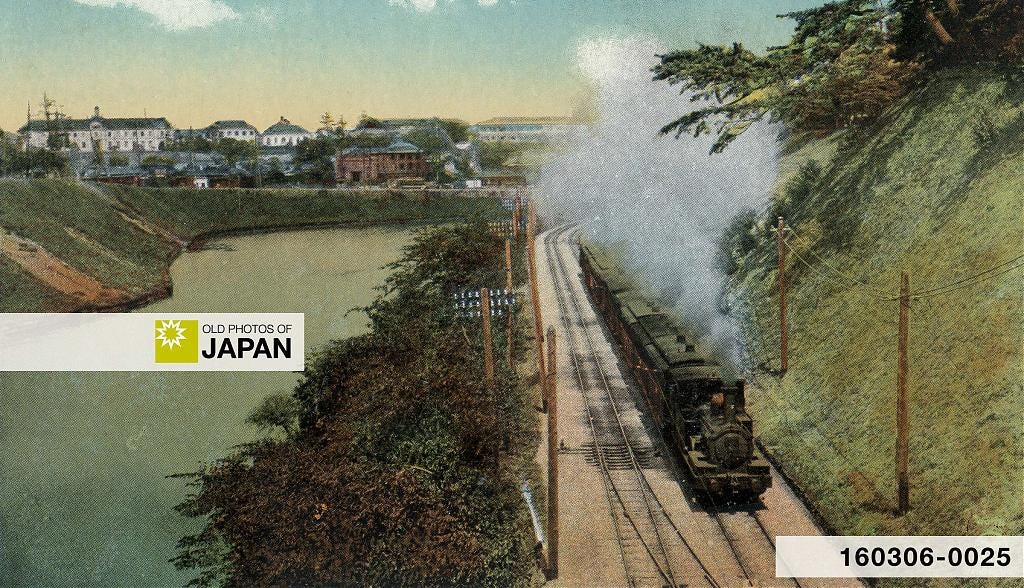

Shinjuku Station was opened in 1885 (Meiji 18) on what grew into the important 34.5 kilometer Yamanote line circling the city.3 It was a tiny station in the countryside, away from the built-up area of the Naitō-Shinjuku way station. Standing alone in the wilderness it saw just 50 passengers a day.4

However, over the next four decades things changed radically. Four additional major railway lines started servicing Shinjuku, as well as two streetcar lines.

By 1928 (Shōwa 3), Shinjuku counted 5 stations (see map below) and handled more passengers than Tokyo Station.5 It had become Tokyo’s most important railway hub and was now easy to reach. Naturally, a vast modern city shot up around it.

Jūnisō Pond was no longer remote, nor rural…

Geisha to the Rescue

Yodobashi’s explosive growth presented great challenges to its town council. Huge investments were needed in infrastructure like roads, sewers and schools. In 1922, Yodobashi created a plan to help raise funds. In a letter, the mayor explained that the town’s fiscal crisis was caused by “unusual” population growth resulting from its “favorable geographical location” and railway network:6

Like the general trend in neighboring towns and villages outside Tokyo City, Yodobashi has also been experiencing unusual development in recent years. It now has over 10,000 households and a population exceeding 50,000. It goes without saying that this trend will become even more pronounced due to Yodobashi’s favorable geographical location as a residential area outside the city proper and the development of its transportation facilities.

Yodobashi Mayor Kiemon Masumoto (1922)

After describing the fiscal challenges in some detail—in particular construction work at elementary schools—the mayor introduced the town’s unusual solution:7

The Jūnisō area in this town has historically been a celebrated place of scenic beauty, known as a recreational space for people from the city. However, in recent years this area has become notorious due to the presence of unlicensed prostitutes and other unsavory elements, leading to a poor reputation. At the same time, local morality has been disturbed and there are concerns that good customs may be harmed.

We therefore request permission to establish a geisha and machiai district within a designated area managed by our town. By leasing this to business operators we hope to generate tax revenue to alleviate the town’s financial difficulties.

Yodobashi Mayor Kiemon Masumoto (1922)

Machiai (待合) literally means wait and meet. The term is a bit vague and its meaning has changed over the years, but during the 1920s and 1930s it was especially used for a certain type of teahouse. Officially these were places with private rooms where geisha entertained their customers.

As such, machiai were popular spots for politicians to meet and entertain each other, as well as constituents and business people. The term machiai seiji (machiai politics) carried the same shady overtones as back-room politics does today.

Because bedding was available and rooms could be rented by the hour, machiai were also a convenient place for amorous and sexual encounters, including those with geisha or prostitutes. In what is arguably the most sensational murder of the 1930s, geisha and prostitute Sada Abe (阿部 定, 1905–?) cut off her lover’s genitals after weeks of love making at various Tokyo machiai.

In other words, machiai did not exactly have a wholesome image.

The mayor’s letter, partly quoted above, introduced Yodobashi town council’s application to the police for Jūnisō to become a so-called nigyō district (二業地, nigyō-chi or two-business district). Once registered with the police, the designated nigyō district was effectively an officially sanctioned geisha district, a hanamachi.8

Hanamachi were popular during the 1920s and 1930s. Tokyo counted 46 of them, at least 20 authorized during the 1920s. Real estate prices often soared after an area was designated, motivating business owners and landlords, as well as strapped town councils, to go this route.9

This popularity is reflected in the number of geisha and shakufu—waitresses that often worked as unlicensed prostitutes. In 1910 (Meiji 43) Tokyo counted 4,160 geisha. In 1926 (Showa 1) there were 10,124, more than twice as many.10 The number of shakufu rocketed to 28,000. Interestingly, the number of officially licensed prostitutes decreased.11

At the time, hanamachi were generally seen as red-light districts. In addition to unregistered sex workers plying their trade here, a substantial number of geisha were believed to offer sexual services as well.

The difference between geisha and prostitutes was often hard to determine.12 Officially, geisha were not allowed to engage in prostitution. The geisha’s job as a refined professional was to entertain with music, dance, and conversation, as she does today. Geisha literally means arts person.

However, in 1928 (Showa 3) some 76 percent of Tokyo’s 10,440 geisha did offer sexual services, according to research by government official and social investigator Yasoo Kusama (草間八十雄, 1875–1946), who wrote extensively on social issues.13

Jūnisō’s application to become a nigyō district therefore shocked organizations fighting for the abolition of prostitution into immediate action. They especially feared that Yodobashi’s initiative would be emulated by other towns in Tokyo.

One of these organizations was the Kakusei-kai (廓清会, Purity Society). It was established in 1911 (Meiji 44) to oppose the reconstruction of the Yoshiwara red-light district after it had burned down. A large part of the November 1922 issue of its flagship magazine Kakusei was devoted to Jūnisō’s nigyō application.

It included an editorial by journalist and politician Saburo Shimada (島田三郎, 1852–1923) who leveled scathing criticism at Yodobashi’s initiative. Authorizing geisha and machiai to raise money for education was thoroughly immoral, argued the former speaker of Japan’s House of Representatives:14

To begin with, what are machiai? The name is special, but they are essentially meeting places for illicit sexual encounters. What are geisha? Aren’t they just prostitutes hiding behind the facade of performing arts? Aren’t machiai and geisha both consumption mechanisms that corrupt public morals? Aren’t they intermediary institutions encouraging the townspeople to spend several times more than the tax revenue received from geisha?

…

For what purpose do these town council members intend to build schools? Surely it is to promote the knowledge and virtue of young people, and to nurture good behavior. What idiocy to set up an institution where women are kidnapped, bought for money, and used as prostitutes that seduce young men, in order to pay for the establishment of schools.

Saburo Shimada, Kakusei (1922)

Many women in Yodobashi urged the Kakusei-kai to campaign against the bill.15 However, the protests had little effect. In 1924 (Taisho 13) Jūnisō became an official hanamachi with 32 machiai and 27 geisha houses.16

Nature to Nightlife

Jūnisō Pond becoming an official hanamachi spelled the definitive end of its role as a natural retreat. Restaurants and machiai sprung up like mushrooms. Modern infrastructure followed. Bit by bit the pond was shrunk. Jūnisō’s once venerated ancient trees were cut down one after the other.

But the hanamachi became a great success. At the height of its popularity during the 1930s there were nearly 100 restaurants and machiai, and some 300 geisha. In great measure this was thanks to a visionary entrepreneur who built magnificent restaurants next to the pond.

Militarism facilitated this success. But it also brought Jūnisō to its knees.

Continue to Part 7 : Jūnisō becomes a celebrated geisha district, then vanishes into thin air.

About the Top Photo

Streetcars and cars on Shinjuku Ōdōri (新宿大通り) during the early 1920s. The tall building on the left became Isetan Department Store in 1935 (Showa 10). The photographer stood with his back towards the railway. The purification plant and Jūnisō Pond were located far behind him on his right. Shinjuku Station is just out of the frame on the right. Unattributed, photo on postcard stock.

Notes

加藤盛慶 (1931). 『東京淀橋誌考』武蔵郷土史料学会, 97–99.

ibid

The line was originally known as the Shinagawa Line. Developed by Nippon Railway it connected Shinagawa with Akabane. It was developed as a freight line for transporting silk products from Gunma Prefecture to Yokohama Port. More sections were added to the line and its name changed to the Yamanote in 1909 (Meiji 42). The loop was completed in 1925 (Taisho 14).

日本国有鉄道新宿駅 (1985).『新宿駅100年のあゆみ : 新宿駅開業100周年記念』日本国有鉄道新宿駅, 20–21.

Waley, Paul (1984). Tokyo Now & Then : an Explorer’s Guide. New York : Weatherhill, 425.

Today Shinjuku Station is used by an average of some 3 million people per day. It is registered as the world’s busiest railway station with Guinness World Records.

淀橋町長升本喜衛門 (1922). 『二業組合設置ノ件二付許可願』in『廓清』 12(10), 37.

ibid

西村 亮彦; 内藤 廣; 中井 祐 (2008). 『近代東京における花街の成立』景観・デザイン研究講演集 No.4, 2008年12月.

ibid

The demand for geisha in Tokyo increased because wealthy people such as politicians and zaibatsu concentrated in Tokyo actively used them. Simultaneously, entertainment consumption by ordinary people in large cities expanded, diversifying the services provided by geisha. 半戸文 (2023). 『1920~30年代東京の遊興に関する小考』東アジア文化研究 第4号 (國學院大學学術情報リポジトリ).

伊藤秀吉 (1930). 『藝妓の現勢分布』in『廃娼資料』廓清会婦人矯風会廃娼聯盟.

Stanley, Amy (2013). Enlightenment Geisha: The Sex Trade, Education, and Feminine Ideals in Early Meiji Japan. The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 72, No. 3 (August 2013), 540.

草間八十雄 (1930). 『女給と売笑婦』汎人社, 20.

The issue of geisha and prostitution during the 1920s–1940s is explored in books such as Autobiography of a Geisha by former geisha Sayo Masuda (増田小夜, 1925-2008), and Rivalry: A Geisha’s Tale by Kafū Nagai (永井荷風, 1879–1959), an author intimately familiar with the pre-war geisha world.

In Autobiography of a Geisha, Masuda described sexual services, reimbursed by an established point system, as an essential part of a geisha’s employment during the 1930s and 1940s. Masuda, Sayo; Rowly, G. G. (2003). Autobiography of a Geisha. New York: Columbia University Press, 62.

Also see the introduction of Nagai, Kafū; Snyder, Stephen (2007). Rivalry: A Geisha’s Tale. New York: Columbia University Press, xi–xii:

“Kafu’s novel is among the franker depictions of the sexual component of the geisha’s duties. Although much has been written about the overlap or lack of one between the art of the geisha and the business of prostitution, Kafu’s account of Komayo’s career gives us a clear sense of the dilemma facing the ambitious geisha. The primary business of the geisha of this period may have been entertainment, not prostitution, yet the nature of the patronage system and the economics of attracting and keeping a danna meant that most women were effectively engaging in a form of limited prostitution with some if not all their customers.”

A 2008 study by historian Caroline Norma states that as late as 1952 an estimated 53,115 women were prostituted illegally in geisha venues. Norma, Caroline (2008). A Past Re-imagined for the Geisha: Saviour of the 1950’s Japanese Sex Industry. Asia Insitute, Traffic 10, 37-56.

For recent social studies on the overlap between geisha and prostitution during the prewar years, read the work by Japanese anthropologist and historian Yu Terazawa, such as 有志舎 (2022).『戦前日本の私娼・性風俗産業と大衆社会: 売買春・恋愛の近現代史』有志舎.

Incidentally, from the Meiji Period (1868–1912) through the early Showa Period (1926–1989) a single term was often used for geisha and prostitutes, geijōgi (芸娼妓).

島田三郎 (1922).『淀橋町會の奇怪議決・賣淫の賦全を以て智德養成の原資に充てんとす』in『廓清』 12(11), 1–3.

村上雄策 (1922).『十二社二業設置請願と反對運動』in『廓清』 12(11), 24.

加藤盛慶 (1931). 『十二社二葉組合 創立大正十三年六月』in『東京淀橋誌考』武蔵郷土史料学会, 377–378.

Jūnisō became a sangyō (三業) district in 1927 (Showa 2).

This is so fascinating. I had no idea and I’m sure many others are surprised to read this history. The name of Yodobashi Camera isn’t just a name but has deep connections to Shinjuku as well. Thank you again for all your research!