Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This is Part 2 of an essay about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

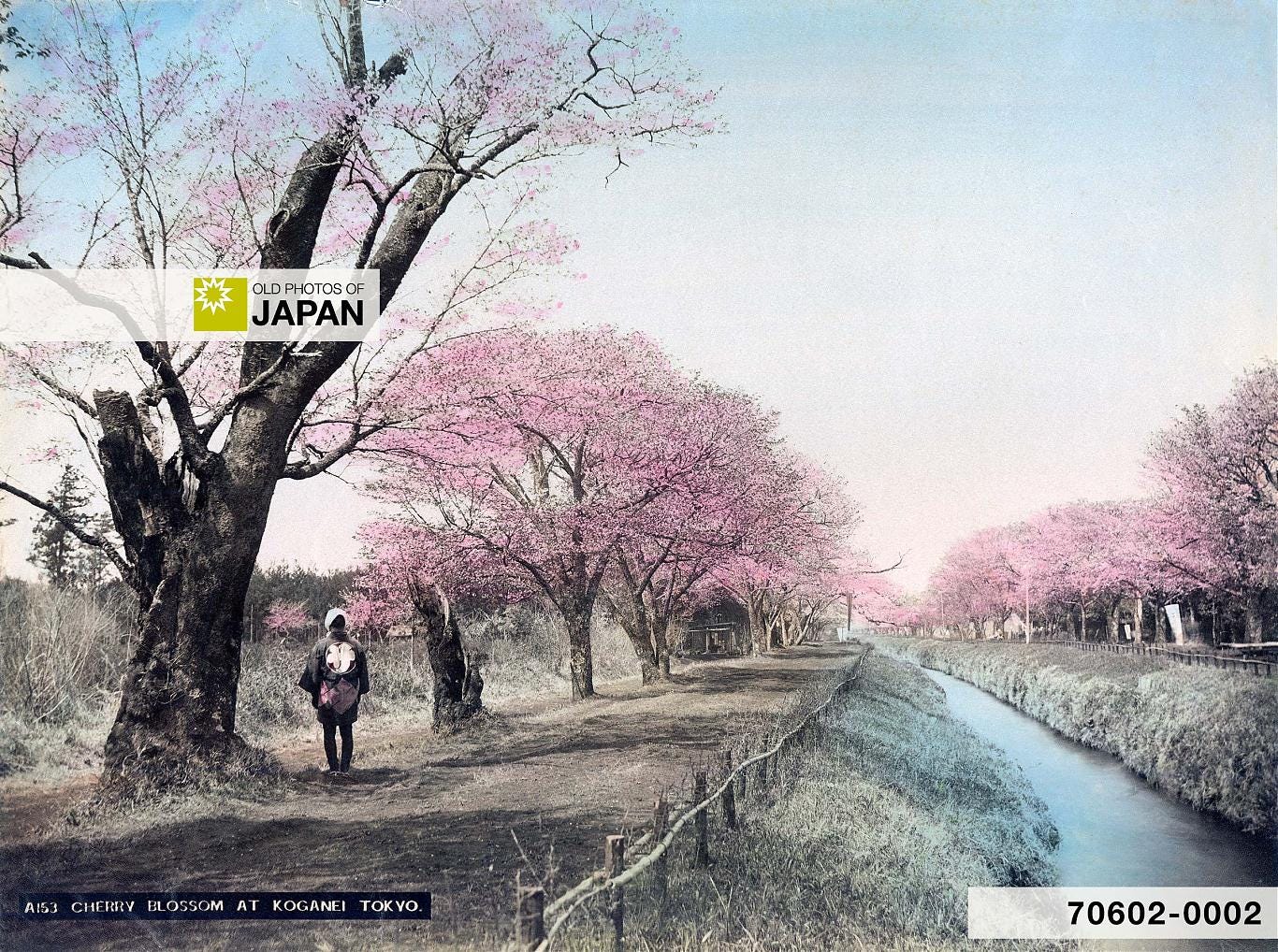

Cherry blossom along the Tamagawa Jōsui at Koganei. The 43 kilometer aqueduct supplied much of Tokyo’s drinking water and played a major role in turning Jūnisō into a place of natural beauty.

As soon as one starts to look at Jūnisō’s origins, the story of Tokyo emerges.

Remarkably, the natural beauty that inspired artists and moved Fukyū to religious rapture was all man-made. It sprung into being because shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) selected Edo to build his power base.

When he moved his clan here in August 1590 (Tenshō 18), Edo was a small fishing village of a hundred houses or so. Much of the area was “a reedy swamp completely covered by water at high tide.”1 There was a castle, but it was abandoned and consisted of a few dilapidated buildings with leaking roofs and stained mats:2

Edo Castle was in ruins. Not a single stone wall was left standing, only earthen embankments; what buildings remained were roofed in wooden shingles, like simple village structures.

Edo, The City That Became Tokyo (2003)

Ieyasu transformed the village into a large town. When he became shōgun in 1603 (Keichō 8) it became the de facto capital. By the mid 1650s, Edo’s population had soared to some 300,000 inhabitants.3 Providing all of them with enough food and water was a massive challenge.

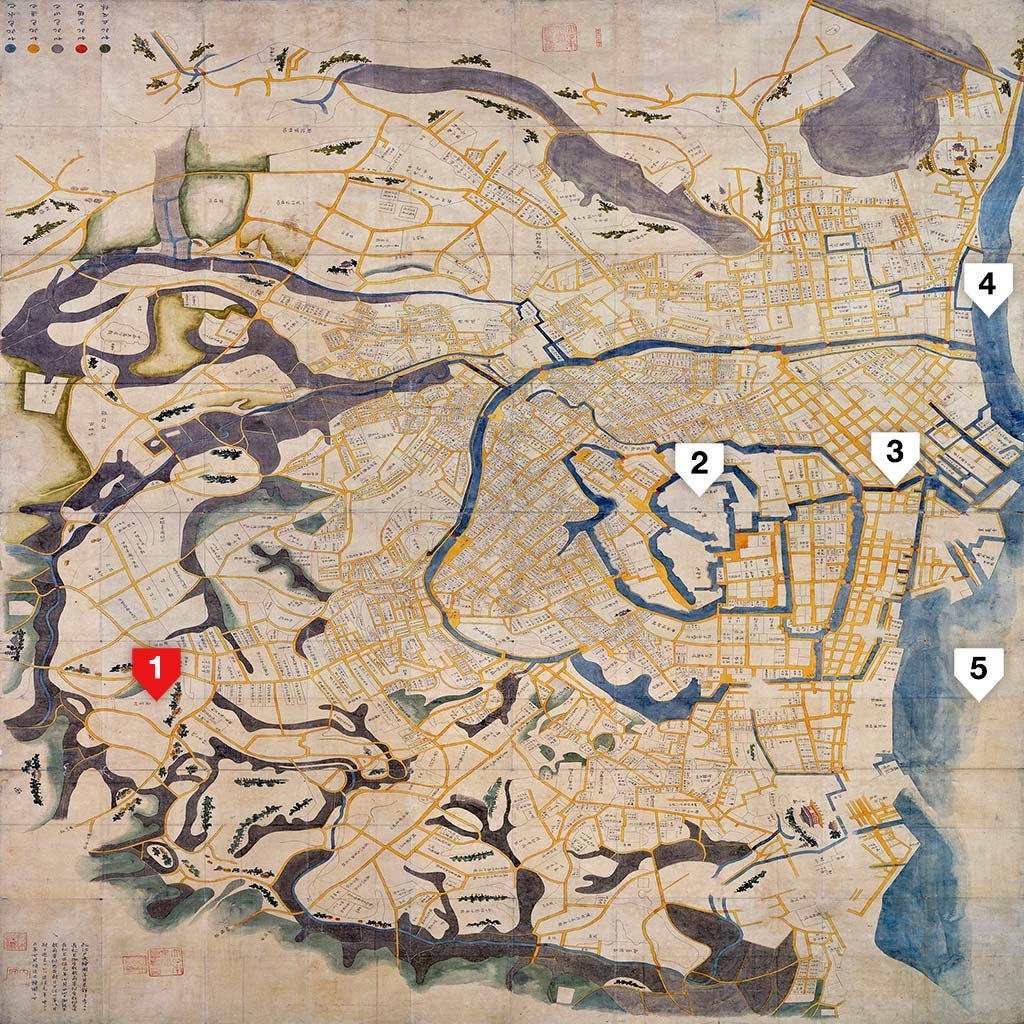

To increase agricultural output, the shogunate built countless irrigation reservoirs (溜池, tameike) in the surrounding countryside. In 1606 (Keichō 11) one was dug right next to Kumano Jūnisō shrine, founded two centuries earlier. The pond that so enraptured Fukyū in 1851 was really a simple reservoir created for farmers.

It actually consisted of two ponds, with a combined length of 320 meters, more than three international soccer fields. At its widest point it measured 47 meters, almost the length of an Olympic sized swimming pool.4 It was large.

In-between the two ponds, right below the shrine, were miniature falls known as Kogane Taki (黄金滝, Golden Falls, 1 on the map), really just two large pipes protruding out of the hillside.5 The water was believed to “cure frenzy, madness, and other ailments.” People came from far to take showers.6

Waterfall

Jūnisō’s famous main waterfall was also a direct result of Ieyasu’s ambitious project to build an imposing capital from scratch. The rapid growth of the population created huge issues with drinking water. Edo was being built on salty marshlands and digging wells was not an option. So the shogunate dug lengthy canals to bring in water from far away. These were known as jōsui (上水).

Two of the earliest jōsui passed close by Kumano Jūnisō shrine. The Kanda Jōsui (神田上水), also known as Kandagawa, passed the shrine in the north and carried water from Inokashira Pond. In 1653 (Jōō 2), the 43 kilometer long Tamagawa Jōsui (玉川上水), supplying water from the Tamagawa River, was dug on the shrine’s south.

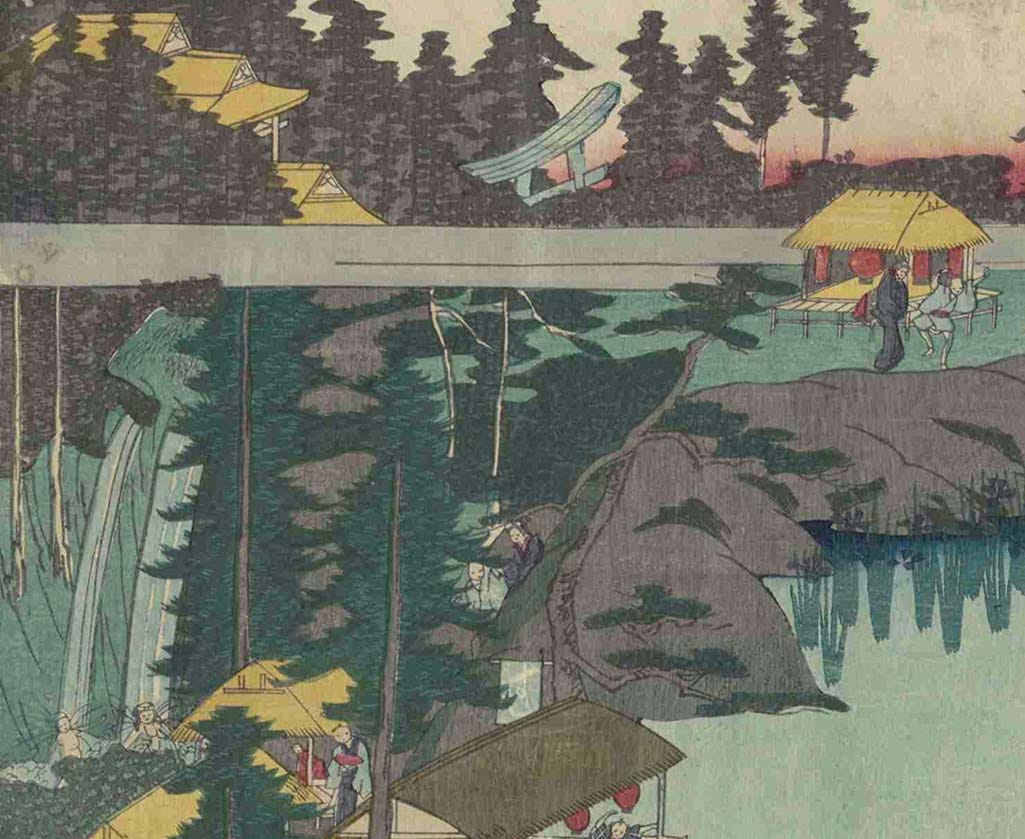

To draw water from the Tamagawa Jōsui to the Kandagawa the two jōsui were connected by a canal, or josuibori (助水堀), in 1667 (Kanbun 7). It passed right by the edge of the shrine grounds. The section next to the shrine was dug several meters deep, creating a sudden cliff. This gave birth to a 4 meter high waterfall known as Ōtaki (大瀧, Great Falls) or Hagi Falls (萩の滝).7

Based on today’s lay of the land many modern accounts place this waterfall north-east of the shrine. But an in-depth 2018 study by two Japanese engineers found that it was actually located on the south-east (3 on the two maps above).8 They based their findings on historic sources, contemporary woodblock prints, and careful calculations of the elevation and water speed of the canal.

By the time the Naitō Shinjuku way-station opened in 1699 (Genroku 12), all the pieces of the puzzle were in place to turn Jūnisō into a celebrated place of natural beauty.9 Jūnisō had grown into a beautiful forested spot with a pond and waterfalls, accessible by good roads.

The timing was right, too. The Tokugawa shogunate had brought a century of peace, prosperity, and culture. People had time, money, and desire for relaxation. The places they choose to relax were overwhelmingly shrines and temples:10

Most of the famous and scenic places in the City of Edo were temples and shrines. In particular, temples with spacious precincts and temples located in the suburbs developed into places of leisure where the public visited to worship and enjoy eating, drinking, and relaxing walks, in addition to visiting on festival days and for annual events. In particular, temples and shrines located within 5 to 10 kilometers from the city center were seen as destinations for sight-seeing and leisure-based day trips.

Discussions on the Religious Space of Edo City (2014)

Jūnisō was about 10 kilometers from Edo’s symbolic city center at Nihonbashi, right at the far end of that range. All that was needed was making Edo’s inhabitants aware of Jūnisō. This happened when in the early 1700s the eighth shōgun Yoshimune (1684–1751) began to visit the shrine for falconry. Literary figures and artists followed.11 Soon, Jūnisō was a popular scenic spot for the cultured.

Kumano Jūnisō shrine, and nearby villagers, also did their best to attract regular people. In 1773 (An’ei 2), 1820 (Bunsei 3) and 1840 (Tenpō 11) the shrine organized gokaichō (御開帳), public exhibitions of a Buddhist image or statue usually kept hidden. During the Edo Period (1603–1868) gokaichō morphed into enormous carnival-like events that were organized by temples and shrines to raise funds.

The shrine’s 1773 gokaichō lasted two months. Sacred treasures were exhibited and teahouses and archery ranges were set up. Two popular kabuki actors donated a large painting on a wooden plaque, which still hangs at the shrine. It has been designated a tangible cultural property by Shinjuku-ku.

The 1820 gokaichō lasted for two and a half months. There were almost 80 food stalls, teahouses and stages for acrobats and puppet shows. The most popular event of this gokaichō were kakunori (角乗) performances, in which acrobats performed routines while balancing on square logs that rolled in the water.

A sailing boat with sake and soy sauce barrels was created in the pond with three square logs floating nearby. An acrobat wearing high geta jumped from the boat onto a log and rolled it with his feet. Next, he climbed a ladder balanced on a log and performed acrobatics on top.

Kakunori can still be observed today. To keep the custom alive, Tokyo’s Koto-ku organizes an annual kakunori event in Kiba Park.

Kumano Jūnisō shrine organized the final gokaichō in 1840, to raise funds for the restoration of the shrine buildings. Once again it lasted for two and a half months. There were some 40 food stalls and teahouses, as well as tents for acrobats and karakuri mechanized puppet shows.

On rafts in the pond there were music, dance and other performances. Villagers and their children created large craftwork displays, including a lifelike doll of a woman sitting on a bamboo bench with a child holding an insect cage.12

The scale of these events illustrate how thoroughly Jūnisō was knit into Edo life. They were even advertised at Nihonbashi, the city’s commercial center.

Foreign Visitors

Though Jūnisō was popular with artists and authors, it is especially thanks to foreigners that we have detailed accounts of Jūnisō on the eve of Japan’s modernization. Enchanted foreign visitors, visiting just after Japan opened its borders in 1859 (Ansei 6), described aspects that locals took for granted.

Continue to Part 3 : Insightful descriptions of Jūnisō by early foreign visitors.

Notes

Sadler, A. L. (2009). Shogun: The Life of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Tokyo, Rutland, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 117.

Naitō, Akira (2003). Edo, the City that Became Tokyo: an Illustrated History. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 23.

Edo Tokyo Digital Museum, Reconstruction of the city after “Great Fire of Meireki”. Tokyo Metropolitan Library. Retrieved on 2024-06-13.

Information provided by Kumano Jinja.

Kogane Taki was also known as Shimizu Taki (清水滝).

Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige placed this description with his 1850 woodblock print of the main falls, included in his Picture Book of Edo Souvenirs, Volume 3 (絵本江戸土産 三編, Ehon Edo Miyage Sanpen). However, this text almost certainly related to Kogane Taki as there are only images of people bathing at that location. Several sources refer to “Kumano Falls” while clearly describing the two pipes of Kogane Taki. From my research it has become clear that the two falls were often confused with each other.

「其二 大滝 近来 この所の池より落る小滝をまうけて 夏月納涼の一助とす 都下の人々こゝに群集し この滝を浴みて逆上を治し 且 發狂等の病を癒さしむ」

野崎正興; 中垣創三 (2018). 『角筈十二社の大瀧に関する一考察(神田川助水堀内の大瀧)』新宿つつじの会.

ibid. The study places the location of the main falls around the entrance of Shinjuku Central Park across the street of the Knot Hotel.

In 1718 (Kyōhō 3), Tokugawa Yoshimune ordered the closing of inns at Naitō Shinjuku. It was reopened as an official way station in 1772 (Meiwa 9). The town continued to exist in the interim.

Matsui, Keisuke (2014). Discussions on the Religious Space of Edo City : The Landscape and Functions of Temples and Shrines. Journal of Geography (Chigaku Zasshi) 123 (4), 451–471 .

Information provided by Kumano Jinja.

安宅峯子 (2004).「第八章 江戸の鎮守の森」in『江戸の宿場町新宿』東京:同成社, 176–184.

Who or whom had the vision to take a salt marsh and see what it could be. Then attract so many to a place of beauty and serenity. I was amazed to see so many attracted to the place so quickly, 300,000 wow!

Very nice! I enjoyed seeing the transformation. Really, incredible engineering. Thank you.