Tokyo 1905/1906 • Shinjuku's Lost Paradise (5)

The natural sanctuary becomes a place to satisfy worldly desires…

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This is Part 5 of an essay about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

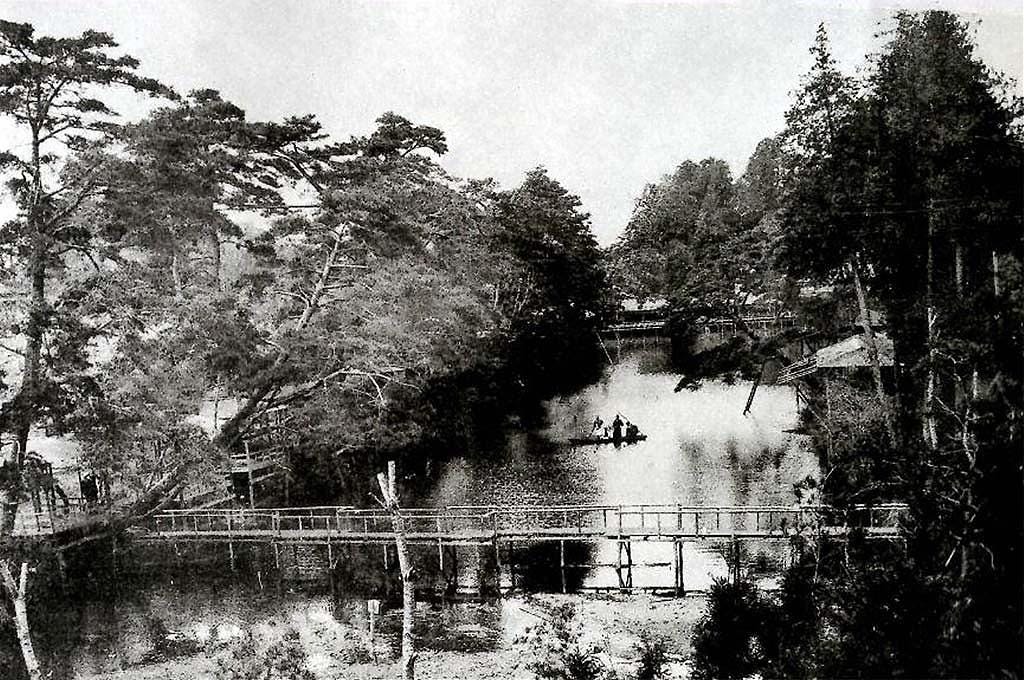

An extremely rare photo of Jūnisō Pond around 1905 (Meiji 38), looking south. Teahouses and restaurants already crowd the pond’s banks and its natural beauty is no longer the main attraction.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Jūnisō Pond was still seen as a natural escape during the hot summer months. The daily newspaper Miyako Shinbun reported on August 15, 1903 (Meiji 36) that during the heat wave that summer the “waterfall” of Jūnisō, together with falls in Meguro, Oji, and other locations, had been “extremely popular”.1

Yet, the pond was clearly changing. A foreign tourist shot the top photo in late 1905 or early 1906. There are no boats yet, and the water level is significantly lower, but otherwise the pond looks almost exactly as in the photographs of Jūnisō a decade later. Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) apparently inspired the construction of the new teahouses and restaurants visible in this print.

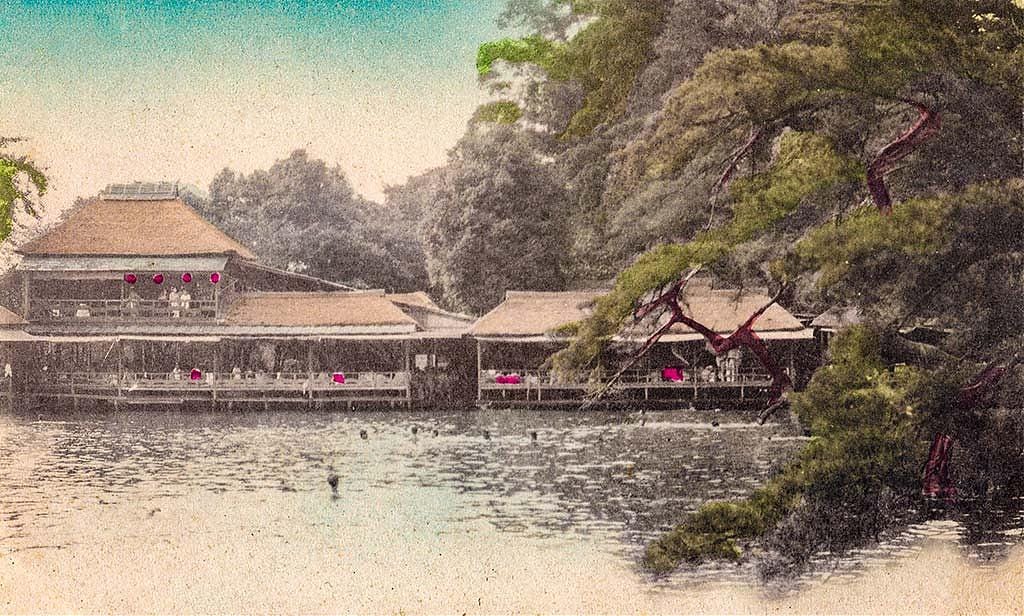

Notice that workmen are landscaping at the far end of the pond. A postcard of ca. 1908 (see below) shows a water garden and a separate, slightly higher, small pond in this area, as well as carefully maintained walkways. This was likely what the workmen were constructing.

The print only measures 6.5 by 8.5 centimeters (2.5 by 3.3 inches). It is tiny. But the buildings and the workmen, and the print’s surprising clarity, make it invaluable as documentation of a crucial point in the pond’s commercialization as a playground. It dates this conclusively to 1905–1906. A worthy addition to the Duits Collection.

Photos of the 1910s and later show a wooden bridge crossing the pond here.

Times of Change

The early 1900s were a transition period in which the past and the future co-existed at Jūnisō. A description by Japanese playwright Shiran Wakatsuki (若月紫蘭, 1879–1962) of a short visit in August 1909 (Meiji 42) could almost have been written two decades earlier.

However, Jūnisō now had entertainment features like a fishing pond, an archery range, and a hanayashiki, a public flower garden. It had become a commercialized playground, apparently attracting thousands of visitors daily.

Wakatsuki mentions three artificial ‘waterfalls’ for showering; the increase suggests that they were a key attraction. But they were no longer shared by both men and women as in the past. Imported Western prudishness now demanded separation by gender. There was even a sign stating that a yukata had to be worn:2

There are three waterfalls, one on either side of the entrance, and one in the center on the left side of the pond. Each waterfall is divided into one for men and one for women. Outside, there is a sign saying “Yukata must be worn”, but when I looked inside the men’s section, I saw many fully naked men slapping each others backs. I heard noisy women’s voices at the female section.

Apparently the falls’ water is drawn from the Tamagawa Josui via the Yodobashi Purification Plant. When I asked one of the children “Is it cold?” he replied, “No, it’s not that cold.”

Besides the waterfalls, there is a fishing pond, an archery range, and the Jūnisō Hanayashiki. In the Hanayashiki, where summer flowers are blooming, mountain lilies are now in full bloom, sending out an extraordinary fragrance even to people just passing by.

After circling the pond, I went up to a teahouse, where a refreshing breeze, free from the dust of the street, cooled me down before I even took off my haori coat. When I asked, I was told that four to five hundred customers visit daily. The prices felt reasonable.

Shiran Wakatsuki (1909)

Jūnisō had not yet turned into a spot of night entertainment in 1909. Although there were lots of visitors during the day, less than a hundred showed up after dark, writes Wakatsuki. The pond was still considered remote.

Among the late visitors were a few women who ordered several bottles of beer. Wakatsuki probably mentions this because, though common, beer was still relatively expensive—a bottle cost as much as ten dishes of buckwheat noodles.3

As the sun began to set, people started to leave the crowded teahouse five, then ten at a time. “Arigatou gozaimasu. Sayonara,” sounded the odd voices of the waitresses sending the customers off as their number gradually decreased.

Soon the lanterns hanging from the rooftops were lit. Carps jumped eagerly out of the water. At the back of the pond, frogs began to croak noisily. Seduced by their voices, two or three large fireflies fluttered from bank to bank like in a dream. The sound of the small waterfalls gradually reverberated more loudly, and the coolness closed in with each passing moment.

Why did so many people leave at this early time? Perhaps because the place is so remote. After dark, barely three to five people visited at a time. The total number of people visiting the tea houses at Jūnisō at night did not even exceed a hundred.

Two or three women with hisashigami (low pompadour hairstyle popular from 1902) who happened to get seated at the next-door tea house, soon started to eat sushi and other dishes. With their faces lined up they looked down at their food. Clad in brightly patterned yukata, they were probably proprietresses reminiscing about the past. To my surprise, two or three bottles of beer were placed next to them.

Shiran Wakatsuki (1909)

Wakatsuki next describes a scene that suggests that geisha were still a bit rare at Jūnisō—they needed to be escorted into and out of the teahouses.

He also beautifully illustrates how customers and waitresses interacted in early twentieth century Tokyo. Simultaneously, it shows that even as the area was being developed, rice paddies still bordered Jūnisō Pond in 1909.4

While I was absentmindedly gazing at the other teahouses, I suddenly heard a stylish sound of shamisen strings being tuned. When I asked the waitress, “Oneesan, that sounds like geisha, doesn’t it?” she replied, “There was Tokiwa shamisen practice during the day, maybe they are still there. Geisha and entertainers come here, but we haven’t seen them for two or three days.”

“But earlier there were two women who looked like geisha.”

“Someone must have brought them here. It is a bit strange that one can take geisha here but you can’t leave without them, right? But in three or four days all will be back to normal.”

Soon after, as the sound of shamisen strings could still be heard, there was a sound as if someone jumped into the water. “Can people swim in this pond?” I asked.

“When the police is not paying attention, people sometimes swim. But the water does not even reach your neck.”

When I said, “So, it is impossible to die, right?” the waitress answered in a strange voice, “Huh?” She stared at my face for a while, then answered, “In the past some people drowned, but with so many buildings around, nobody can drown anymore.”

By the time I heard her last words, the waitress had already gone outside. I don’t know if she worried that perhaps there had been a double suicide after all. But, no matter how much I clapped my hands for some time afterwards, there was no response.

As I left the teahouse, a waitress came running after me—her feet loudly thumping the ground. When I turned around and asked, “What is going on?” she said, “I am sorry to disturb you, but please take this.” With one hand she held out a paper lantern, perfect for walking along the dark rice paddy paths.

Edo employees are truly in their own class.

Shiran Wakatsuki (1909)

Den of Lust

Now starts a period of radical change. By 1912 (Meiji 45), Jūnisō has turned into a shady red light district. An article published in the magazine Sunday (サンデー) that year paints a totally different picture from Wakatsuki’s idyllic report only three years earlier.

The headline shouts, Quiet Poetic Spot Turned into Den of Lust. Lewd and Vulgar Behavior at Rural Jūnisō. The author shares two pages of dismay after visiting the “unique enchanted place” where “artists and authors went to relax”.5

In the past, five or six teahouses were dotted along the edge of the pond. While sipping tea, you could cherish the pond’s natural beauty and cool down to your heart’s content with the refreshing breeze blowing from the shade of the trees washing over your light summer wear.

It was a place where for a single fifty sen silver coin (half a yen) you could cook a fresh carp on the spot, make carp miso stew and sashimi, enjoy their flavors, and get pleasantly tipsy.

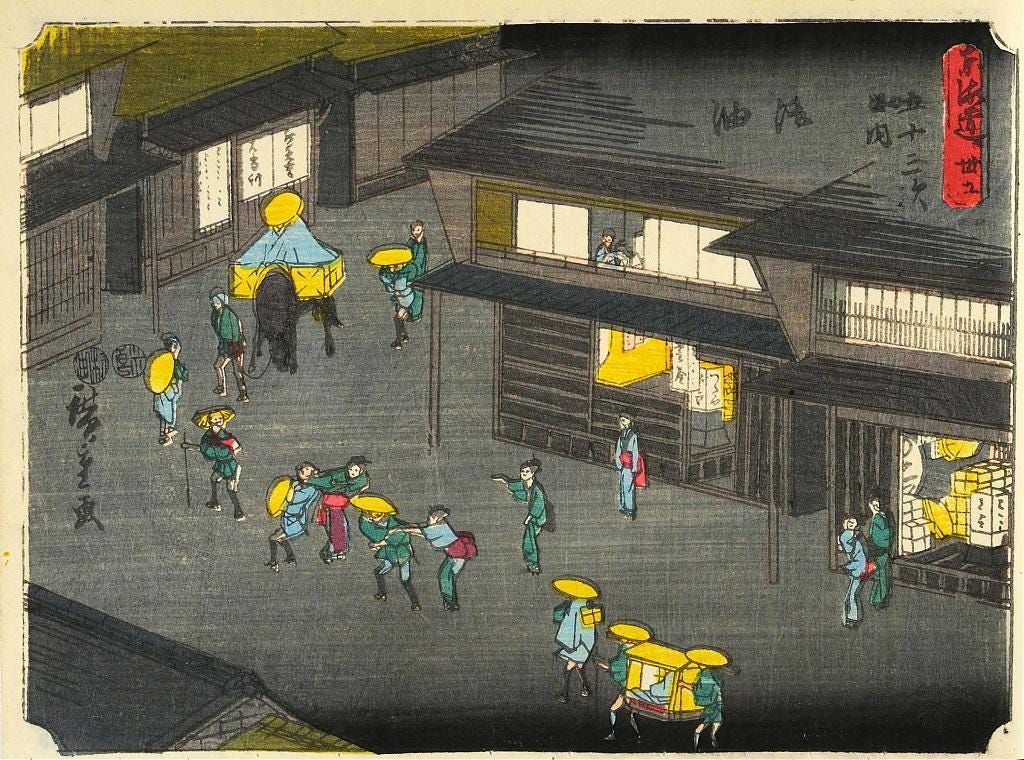

But now, two-story restaurants and brothels have been built all around the pond. Like lodging touts at Zenkoji Temple or Enoshima (popular places of pilgrimage, and therefore prostitution), heavily painted-up women with rough lewd looks in their eyes rush out of each place, four or five at a time, as soon as they see a customer. They jump in front of you and shout, “Come on in, have a bite, enjoy yourself!” Some even pull you by the sleeve and say seductively, “Are you just passing through? Come in and have some fun.”

Den of Lust, Sunday (1912)

The author next explains that the once beautiful pond where the “carps danced” is covered in floating algae, the surface murky and dark.

As he walks past the open-air teahouses he is surprised to see what he calls “tickling and pinching” taking place out in the open. He identifies the women as shakufu (酌婦), a term generally translated as waitress or barmaid. But during this period of time the majority of shakufu were unlicensed prostitutes.

Circling the pond, he observes two shakufu entertaining four or five “proud young men” wearing nothing but hachimaki headbands and black fundoshi loincloths. A man in a yukata lies on the floor with a woman, her yukata untied and open at the front. Another man, satiated from too much sake and fish, stares vacantly outside. Women constantly approach the author to “come in and have fun”.6

He then describes in detail how a “retired man of 54 or 55 years old” is enticed by a shakufu less than half his age:7

She edged herself closely to the old man. As she flirted she said “What are you talking about?” and pinched the old man. He glowed with satisfaction and with a vulgar laugh repeatedly said, “I may be bald but I am full of passion.”

“Oh, stop it,” the shakufu responded, coyly drawing herself away from the man. Then, she drew close again and whispered, “Don’t tease me. Come with me for a good time.” She pressed her cheek against his and they breathed in unison.

The old man nodded slightly in agreement. The two stood up from the messy table scattered with the leftovers of food and drink, slipped into geta, and disappeared hand in hand into a room in the back.

Den of Lust, Sunday (1912)

The author also visits a place advertising itself as a “hot spring”. But the water is “extremely murky, as if it had been drawn from a pond.” The sake and food disappoint him even more. The sake tastes bitter, and the broth soup he ordered is “like soy sauce with hot water poured over it, completely inedible.” As he leaves he wonders “if anyone would be crazy enough to visit the Tsunohazu area a second time just to get bitten by mosquitoes.”8

Railways and Geisha

At the time of the above articles Jūnisō was still a remote place with rice paddies. By the 1920s it was heavily urbanized. Jūnisō was no longer a remote place beyond the edge of the city.

This was partly because of an explosion of railways connecting to Shinjuku. The resulting population growth presented great challenges to Yodobashi’s town council. Huge investments were needed in infrastructure. To solve this problem an unusual solution was introduced.

Exactly ten years after the Sunday article, the Yodobashi Town Council applied to the police to make the illicit dealings that were taking place at Jūnisō legal by turning the area into an official geisha district, so those dealings could be taxed.

Continue to Part 6 : Jūnisō becomes an official geisha district, delighting some, enraging others.

Notes

『◇ 瀧 ◇ 大流行』(1903-08-15) 新聞集成明治編年史 第十二卷 : 都新聞, pp. 99.

若月紫蘭(明治44). 東京年中行事 下. 東京:春陽堂, 152–153.

ibid.

ibid.

The reference to Tokiwa practice is interesting—Japanese author Katai Tayama mentions in his book Time Passes On that a Tokiwazu shamisen master lived in the neighborhood: 田山花袋(1952)『時は過ぎゆく』東京:岩波文庫, 338.

『静寂の詩境此淫魔窟と化す・郊外十二社の淫風猥俗』(1912-07) サンデー (188, 12–13).

ibid.

ibid.

ibid.

Interesting transition at that time. Transportation had a lot to do with it.

The start of “red light districts” in Japan? Taxing these activities made it possible and above board. Very interesting photos. One of the gals had a nice shibori yukata.