Birth of a Nation

How measures to prevent samurai from waging war against the government created mass tourism and a nation.

Hi, I am Kjeld Duits and I created Old Photos of Japan.

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for daily life in old Japan. I track down and acquire rare vintage prints, research and conserve them, and share the results online for everybody to enjoy and learn from.

Please help support this valuable work.

This rare photo from 1871 shows Tokyo’s Nihonbashi Bridge made famous in countless woodblock prints. A year after Austrian photographer Michael Moser shot this scene, the bridge was torn down and rebuilt.

The celebrated Nihonbashi—literally Japan Bridge—was the zero-point of Japan’s road system. First built in 1603 (Keichō 8), it was located next to the city’s fish market and measured only about 50 meters.

This surprisingly humble bridge was the starting point of Japan’s important five centrally administered highways known as the Gokaidō (五街道, Five Highways). During the Edo Period (1603–1868) they connected Edo (current Tokyo) with the rest of the country.

This essay explores the fascinating role these roads played in creating the Japanese nation, and Japanese culture. They also made Japan the world’s first country with a large tourist industry. For example, in 1830 (Bunsei 13) some five million travelers visited what is today Mie Prefecture.

Make yourself comfortable, discover, and enjoy.

Japan’s Roads

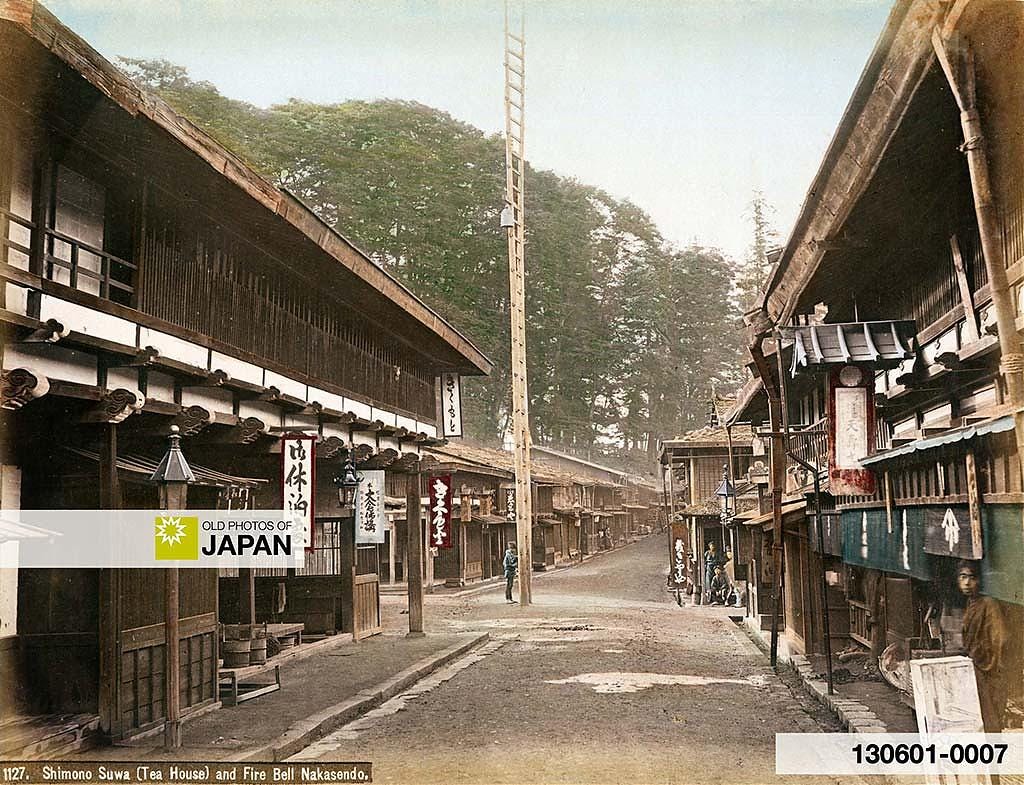

Thanks to woodblock artists Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川 広重, 1797–1858) and Keisai Eisen (渓斎 英泉, 1790–1848), two of the Gokaidō’s five roads have become world famous: the Tōkaidō and Nakasendō (also known as Kiso Kaidō).

But Japan had an extensive and well-developed road system that reached far beyond these two important roadways.

Five highways administered by the Tokugawa government radiated out of the de facto capital of Edo: the Tōkaidō, Nakasendō, Kōshū Kaidō, Nikko Kaidō, and Ōshū Kaidō. These five official roads were connected to major subroutes administered by local daimyō (provincial lords), which in turn connected to local trails and roadways.

The map below shows the major connections in this transport system during the Edo (1603–1868) and early Meiji (1868–1912) period. The Gokaidō are shown in red, green, violet and orange, major subroutes in yellow, and sea routes in blue. In spite of many mountains hindering travel, the country was remarkably well-connected.

Stability and Stimulus

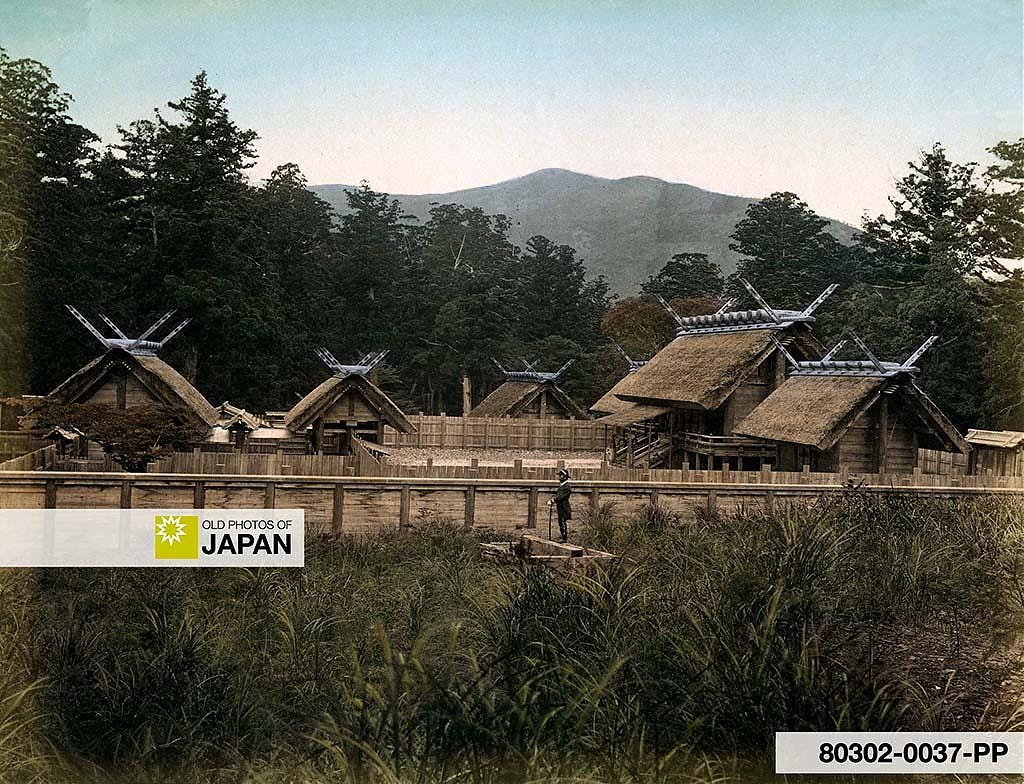

The backbone of this road system was first developed in the 7th century. But Japan’s roads truly became important when the Tokugawa shogunate consolidated its power in the early 1600s, effectively ending over a century of continuous warfare and social upheavals.

The Gokaidō roads were initially intended to facilitate travel by government officials and military forces. But their function and form changed dramatically when in 1635 (Kanei 12) the Tokugawa government forced tozama daimyō (外様大名), lords seen as outsiders by the shogunate, to reside in Edo every other year, a mandatory alternate attendance system known as sankin-kōtai (参覲交代).

Seven years later fudai daimyō (譜代大名), the most trusted hereditary vassals, were also obliged to do so. Now some 260 daimyō and their large groups of retainers regularly marched between their domain and Edo.

The smallest domains had just a hundred men or so in these processions, but the largest were massive. The entourage of the Kaga domain, based in Kanazawa, counted 3,500 men. Tosa, in what is today Kōchi Prefecture, had 2,500.1 A huge number of men were also employed to transport provisions and supplies.

Incidentally, the numbers were even more impressive when the Tokugawa shōguns took to the road. When Tokugawa Ieharu (徳川家治, 1737–1786) traveled to Nikkō to honor the shogunate’s founder at the Tōshō-gū shrine his procession counted a staggering 230,000 people and 305,000 horses.2

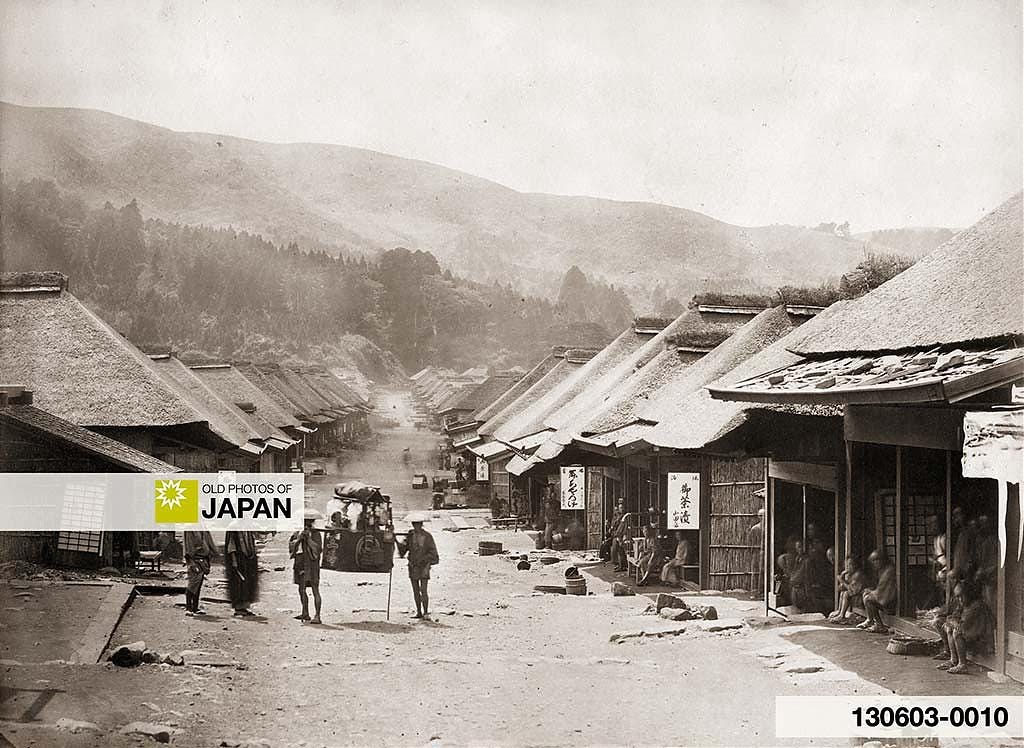

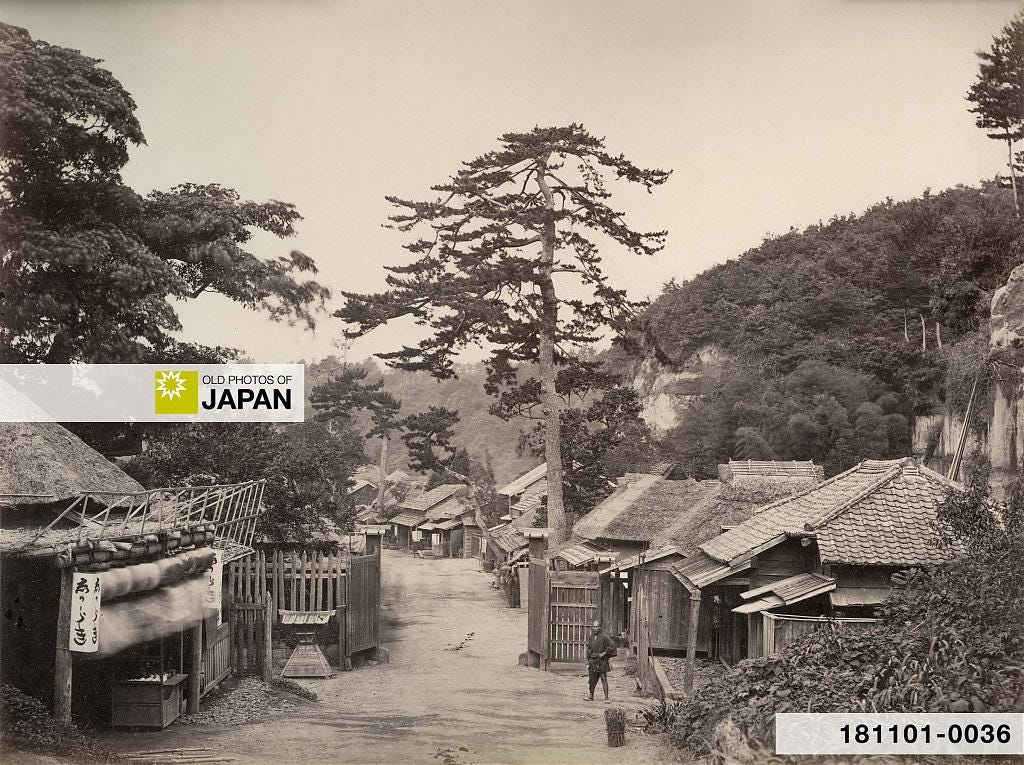

These hundreds of thousands of travelers had to be fed, housed, and moved across bodies of water. This brought about a drastic expansion of Japan’s road network.3 As most travel was on foot, post towns were established within a day’s walking distance from each other. The Tōkaidō ultimately counted 57 of such shukuba (宿場) or shukueki (宿駅). The Nakasendō had even more: 69.

Each station hosted at least one official inn, a honjin (本陣), for daimyō and their top ranking officials, as well as inns for their subordinates. A range of support services, such as horses, porters, and ferries, and inns for ordinary travelers were also established. Soon, accommodations started to serve meals and restaurants were created. Travelers no longer needed to bring their own food.

As this travel infrastructure was built, new growth opportunities emerged. For example, a local souvenir industry developed thanks to daimyo and their retainers purchasing local gifts and delicacies on their journeys.4 Such regional specialties, known as meibutsu (名物) or meisan (名産), are popular to this day.5

Maintaining residences in two places, and regularly marching between Edo and their domain with many hundreds or even thousands of retainers, put an enormous financial strain on the daimyō. It swallowed half to three-quarters of a domain’s disposable income.6 This greatly limited the daimyō’s ability to wage war, which contributed to political stability.

This stability and the redistribution of daimyō wealth to the commoners servicing these forced travelers created a powerful economic stimulus that cannot be overstated—the towns along the roads flourished. As did Edo.

The connection between infrastructure and economic development was noticed. In 1721 (Kyōhō 6) the significance of roads to both governance and commerce was emphasized by the influential administrator Tanaka Kyugu (田中丘隅, 1662–1729).

He based his observations on his experience as the head of Kawasaki, the second station on the Tōkaidō. In a celebrated opinion paper submitted to the shogunate, Tanaka compared the nation’s roads to a body’s blood vessels:7

A country’s roads are as crucial as the arteries in the human body, working ceaselessly. Is there anything more influential for governing the country? Roads are the nation’s most important facilities for the country’s peace of mind and developing commerce for the people.

Tanaka Kyugu, Minkan Seiyō (1721)

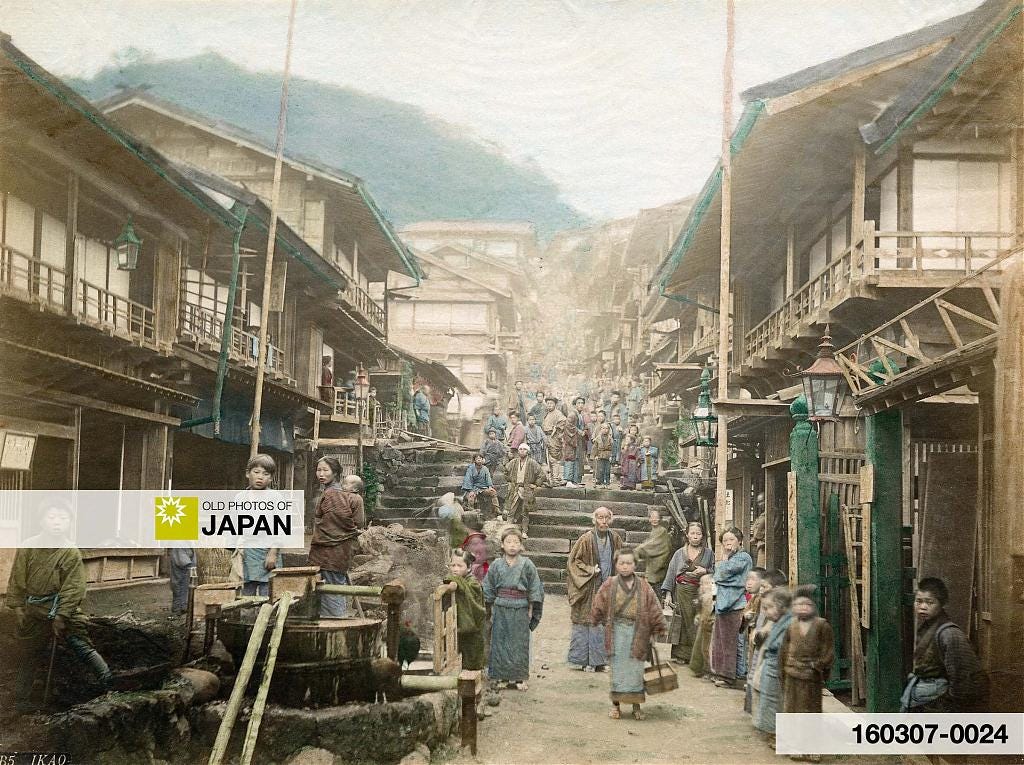

Birth of Tourism

By the late 1600s, Japan had a solid travel infrastructure that could be used by all travelers, including commoners. There were inns for lodging, teahouses for resting, and restaurants for eating. Porters, kago (litters), and horses could be rented. There were even delivery companies for sending luggage ahead, as well as a nationwide credit system so that travelers need not carry all their cash.8

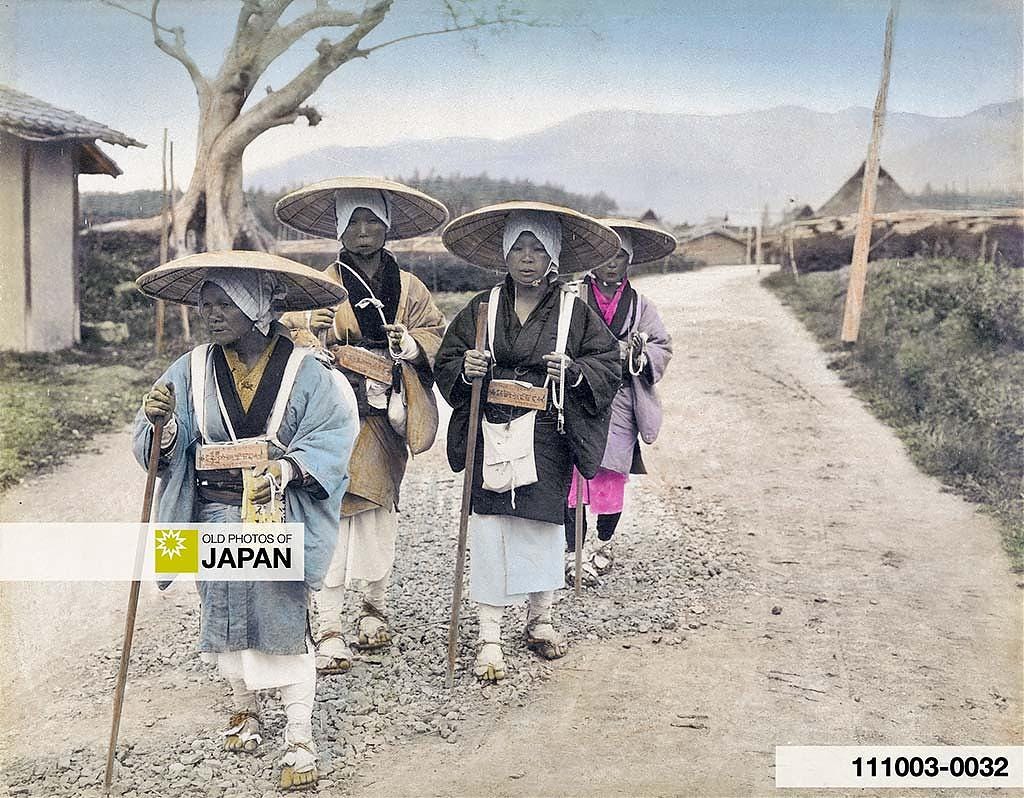

As economic prosperity increased, commoners hit the road. Officially, the authorities discouraged travel. Written permission was required in the form of a travel permit and travel was only allowed for business, health reasons, pilgrimage, and emergencies, like the death of a family member. Travelers got around this by going sightseeing under the guise of pilgrimage or medical treatment.9

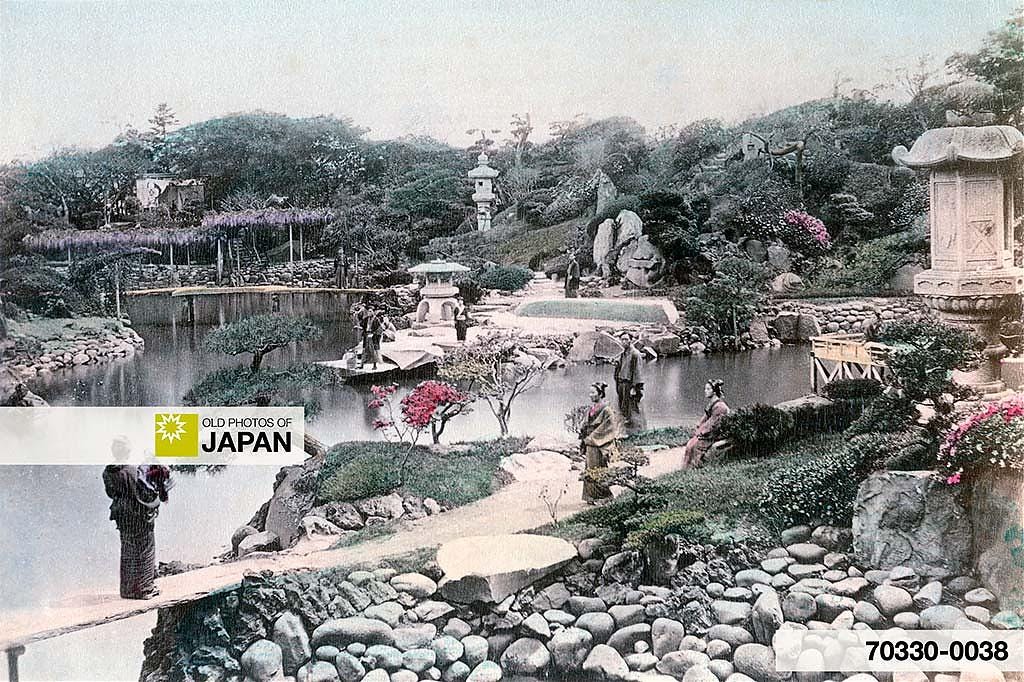

But pleasure was clearly the true motive. Hot springs, temples and shrines were not only surrounded by inns and restaurants, but also souvenir shops, theaters and brothels. The Furuichi entertainment district at Ise Shrine—one of Japan’s most sacred Shintō shrines—hosted 70 brothels with a thousand prostitutes.10

Books noted this love for pleasure travel. Kyōkun Manbyō Kaishun (教訓万病回春, Teachings for Recovering from All Kinds of Illness), published in 1771 (Meiwa 8), introduced it tongue-in-cheek as “an unbelievably infectious illness.”11

Recently an unbelievably infectious illness is widely prevailing. There are so many people who are going to travel for pleasure every year, owing to freedom of time and money, though the nominal purpose of travel is for visiting hot springs for medical treatment. Not only men, but also many women, who asked their husbands to stay at home and to beg a big amount of money for their travel expenses, went travelling widely for pleasure.

Kyōkun Manbyō Kaishun

The number of travelers went through the roof. In 1702 (Genroku 15), the Tōkaidō alone saw around a million travelers.12 This estimate excludes samurai traveling for sankin-kōtai. In years considered as auspicious for visiting Ise Shrine the number of travelers multiplied.

In 1830 (Bunsei 13), for example, some five million people went on pilgrimage to Ise, many of them women and children under the age of sixteen.13 At the time Japan’s population stood at only 32 million. Let those two figures sink in for a moment: one out of six Japanese visited Ise that year.14 On foot.

The massive numbers of travelers astonished foreign observers. German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716) who lived in Japan from 1690 (Genroku 3) through 1692 (Genroku 5) mentioned both the huge crowds on the highways and the Japanese lust for travel:15

An incredible number of people daily use the highways of Japan’s provinces, indeed, at certain times of the year they are as crowded as the streets of a populous European city. I have personally witnessed this on the Tōkaidō, described earlier, apparently the most important of the seven highways, having traveled this road four times. The reason for these crowds is partly the large population of the various provinces and partly that the Japanese travel more often than other people.

Engelbert Kaempfer

Shuzo Ishimori (石森秀三, 1945), a pioneer of the anthropology of Japan’s tourism, argues that the popularization of tourism achieved by the early Edo period was the earliest in the world.16

[In the early modern age] in Britain travel for pleasure was mostly undertaken by the ruling class and other people had very limited chances to go traveling, while in Japan popularization of travel for pleasure even by ordinary people was realized during the eighteenth century.

Shuzo Ishimori (1989)

In European countries leisure tourism only became this popular when railways were established from the middle of the nineteenth century—a century after Japan.17

A second tourism boom in the late 1700s and early 1800s coincided with the rise of new media like illustrated books and colored ukiyoe woodblock prints. Publishers and artists jumped on the trend and published an astonishing number of maps, guidebooks, and woodblock prints of landscapes.18 The latter by major artists like Utagawa Hiroshige and Keisai Eisen, mentioned in the introduction of this essay.

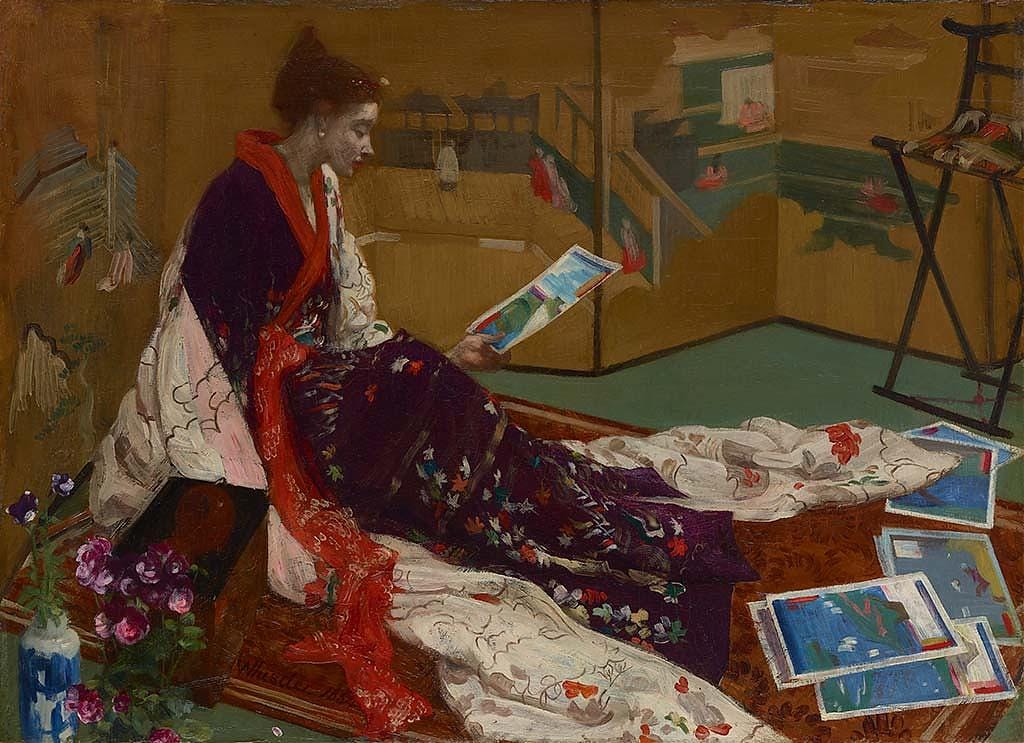

When these ukiyoe reached Europe in the second half of the 1800s they inspired influential artists such as Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), Claude Monet (1840–1926), and countless others exploring new ways of expressing the world.

One could say that in a delightful roundabout way the sankin-kōtai, that forced daimyō and their retainers to spend half of their time in Edo, helped launch the modern art movement.

Freedom and Nation

In the early 1800s, as more and more Japanese were discovering the attractions of travel, Japanese author Jippensha Ikku (十返舎 一九, 1765–1831) described the freedom and new discoveries they experienced:19

The proverb says that shame is thrown aside when one travels, and names and addresses are left scrawled on every railing. Yet it is a consolation when one is travelling to meet people from one’s own province, even although they have the word deaf written on their hats.

Naturally one is curious about the people who are travelling the same roads, and those whose fates are linked together at the public inns do not always have their marriages written in the book of Izumo. They are not tied by convention as when they live in the same row of houses, but can open their hearts to each other and talk till they are tired.

On the road, also, one has no trouble from bill-collectors at the end of the month, nor is there any rice-box on the shoulder for the rats to get at. The Edo man can make acquaintance with the Satsuma sweet-potato, and the flower-like Kyōto woman can scratch her head with the skewer from the dumpling.

If you are running away for the sake of the fire of love in your heart, you can go as if you were taking part in a picnic, enjoying all the delights of the road. You can sit down in the shadow of the trees and open your little tub of saké, and you can watch the pilgrims going by ringing their bells.

Truly travelling means cleaning the life of care. With your straw sandals and your leggings you can wander wherever you like and enjoy the indescribable pleasures of sea and sky.

Jippensha Ikku, Hizakurige (1802–1822)

Even though we are no longer wearing straw sandals and leggings, Jippensha’s words still ring true in our mobile and well-connected world saturated with travel, imagery, and information. Imagine what they meant to readers two centuries ago.

Many of his readers would have rarely traveled beyond a few hours’ walk from their home. They would have never seen anything or anyone outside their immediate surroundings. He was writing about a new freedom.

Thanks to the shogunate’s roads the “world” now lay at their feet.

That freedom created a nation. The sankin-kōtai system brought people from all over the country, and from different social backgrounds, in contact with each other.

Historians have often said that “Edo culture” spread from Edo to the localities. American historian Constantine N. Vaporis however argues that culture also flowed to Edo, as well as between localities. All these cultural and economic interactions throughout Japan gave rise to a “national culture.”20

Alternate attendance promoted the circulation of culture and demolished social and cultural boundaries, so that by the end of the eighteenth century, or beginning of the nineteenth, there was an integrated or “national culture” in Japan.

Constantine N. Vaporis, Tour of Duty (2008), 6

In essence, sankin-kōtai and the excellent road system gave birth to the concept of Japan as a nation. The culture and the image that the Japanese people created of themselves during the Edo Period is still seen as representative of Japan today.

This publication is reader-supported. Please help me research and save Japan’s visual heritage of everyday life.

Related Articles

Read more articles about travel in old Japan.

About the Top Photo

The top photo of the Nihonbashi Bridge in Tokyo was photographed by Austrian photographer Michael Moser (1853-1912) and published in The Far East Magazine in 1871 (Meiji 4). Moser was in Japan from 1870 (Meiji 3) through 1877 (Meiji 10) and took this photograph when he was only 18 years old.

The albumen print shows the wooden bridge shown on hundreds of thousands of ukiyoe woodblock prints. It is an extraordinary photo because only a year later, in 1872 (Meiji 5), this bridge was torn down and reconstructed. A few decades later, in 1911 (Meiji 44), this new wooden bridge also vanished. It was replaced by a stone one which still stands today.

Recommended Reading

Fabricand-Person, Nicole (2011). The Tōkaidō Road: Journeys through Japanese Books and Prints in the Collections of Princeton University. The Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. 73, No. 1 (Autumn 2011), 68–99.

Goree, Robert (2020). The Culture of Travel in Edo-Period Japan. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History.

History of Roads in Japan. In: 2021 Roads in Japan. Road Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.

Ishimori, Shuzo (1989). Popularization and Commercialization of Tourism in Early Modern Japan. Senri Ethnological Studies 巻 26, 1989-12-28.

Jippensha, Ikku; Satchell, Thomas (1960). Shanks’ Mare. Being a translation of the Tokaido volumes of Hizakurige, Japan’s great comic novel of travel & ribaldry by Ikku Jippensha (1765–1831). Vermont, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.

Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos (1995). Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan. Harvard East Asia Monographs.

Vaporis, Constantine (2012). Linking the Realm: The Gokaidô Highway Network in Early Modern Japan (1603–1868). In: Highways, Byways, and Road Systems in the Pre-Modern World. Wiley-Blackwell.

Vaporis, Constantine (2008). Tour of Duty: Samurai Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Notes

Vaporis, Constantine (2008). Tour of Duty: Samurai Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 75–76.

今野信雄 (1986)『江戸の旅』岩波書店, 69.

Ishimori, Shuzo (1989). Popularization and Commercialization of Tourism in Early Modern Japan. Senri Ethnological Studies 26-1989, 184.

Vaporis, Constantine (2008). Tour of Duty: Samurai Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 205–236.

Jippensha, Ikku; Satchell, Thomas (1960). Shanks’ Mare. Being a translation of the Tokaido volumes of Hizakurige, Japan’s great comic novel of travel & ribaldry by Ikku Jippensha (1765–1831). Vermont, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.

Vaporis, Constantine (2008). Tour of Duty: Samurai Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 27.

武部健一著(1992)『道のはなしⅠ』技報堂出版.

From Minkan Seiyō (『民間省要』Notes on Rural Administration):「国土における道路は、あたかも人体の血管のように大切なもので、一瞬もやむことなく運行されている。国を治める働きとして、これに過ぎるものがあるだろうか。国を安んじ、万民の交易のための、第一の国家の重要な施設である。」

Ishimori, Shuzo (1989). Popularization and Commercialization of Tourism in Early Modern Japan. Senri Ethnological Studies 26-1989, 188

Goree, Robert (2020). The Culture of Travel in Edo-Period Japan. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Retrieved on 2024-01-15.

Ishimori, Shuzo (1989). Popularization and Commercialization of Tourism in Early Modern Japan. Senri Ethnological Studies 26-1989, 185.

ibid, 180.

ibid.

This figure is based on the written record of the number of ferryboat crossings at Lake Hamana in Shizuoka Prefecture. In 1702 (Genroku 15) the ferryboats crossed the lake 44,764 times. Assuming that each boat ferried about 20 persons the total comes to 895,280. Additionally, an unknown number of people did not use the ferryboats and walked around the lake.

Goree, Robert (2020). The Culture of Travel in Edo-Period Japan. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Retrieved on 2024-01-15.

鬼頭宏(1996). <調査>明治以前日本の地域人口. 東京:上智經濟論集 41(1・2), 65–79.

Kaempfer, Engelbert; Bodart-Bailey, Beatrice M. (1999). Kaempfer’s Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 271.

Ishimori, Shuzo (1989). Popularization and Commercialization of Tourism in Early Modern Japan. Senri Ethnological Studies 26-1989, 192, 190.

Scaglione, Miriam; Ohe, Yasuo; Johnson, Colin (2021). Tourism Management in Japan and Switzerland: Is Japan Leapfrogging Traditional DMO’s Models? A Research Agenda. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021. Springer, 389–402.

Bolitho, Harold (1990). Travelers’ Tales: Three Eighteenth-Century Travel Journals in Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 50, No. 2 (Dec., 1990), 485-504. Retrieved on 2024-02-24.

Jippensha, Ikku; Satchell, Thomas (1960). Shanks’ Mare. Being a translation of the Tokaido volumes of Hizakurige, Japan’s great comic novel of travel & ribaldry by Ikku Jippensha (1765–1831). Vermont, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 237.

Vaporis, Constantine (2008). Tour of Duty: Samurai Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 6.