Tokyo, 1890s • Shinjuku's Lost Paradise (4)

A pond lost to history tells Tokyo’s story…

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This is Part 4 of an essay about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

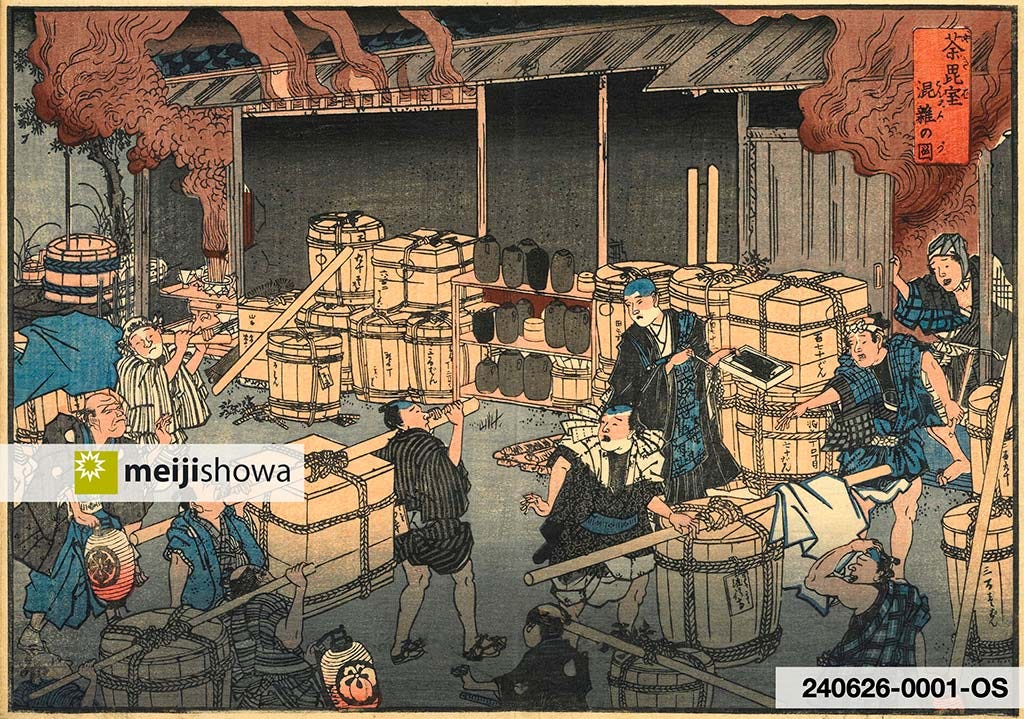

A painting of Jūnisō Pond as it looked during the 1890s, the period when modernization first reached the area. This article introduces revealing first-hand accounts of these, seemingly innocent, early changes.

The 1860s brought drastic changes to Japan, especially to Edo. In 1862 (Bunkyū 2) the Sankin-kōtai system, which forced daimyō (feudal lords) to retain a large residence in Edo, was reformed. Daimyō’s eldest sons and wives could leave Edo, and the number of retainers at Edo residences was cut.

More radical reforms followed after imperial rule replaced the shogunate in 1868. The domains were completely abolished in 1871 (Meiji 4), causing most remaining daimyō family members and retainers to leave Tokyo.

Daimyō estates close to the former Edo Castle—now the Imperial Palace—became government offices, while abandoned estates on the city’s outskirts were turned into agricultural land. Especially tea and mulberry were planted, resulting in the large tea plantations introduced in Part 1.

Tokyo’s samurai exodus caused its population to plunge from over 1.1 million in 1850 to 671,000 by 1878 (Meiji 11).1 Newspapers reported that fewer people visited Jūnisō Pond; by the early 1880s it started to look dilapidated.

In 1885 (Meiji 18) massive renovations were made “to restore the area to its former glory.”2 Buildings and other structures were repaired, the water level of the pond was raised, irises were planted along the banks, three to four teahouses were built, as well as two places where Western liquor was served.3

The renovations made Jūnisō “a perfect recreation garden for escaping the summer heat,” wrote daily newspaper Nichi Nichi Shimbun in June of that year.4 In August, the Yomiuri Shimbun declared the renovations a great success:5

The place was in decline in recent years, and if repairs had not been made, there would have been fewer visitors and business would have been terrible. But thanks to the repairs to the waterfall basin and the surrounding area this year it has become clean and tidy. Due to the increase of visitors, the kakejaya (teahouses) and other shops were so crowded that it was impossible to move.

Yomiuri Shimbun, August 23, 1885

This was the first innocent step towards Jūnisō’s transformation from a natural sanctuary where “worldly desires vanish” into a place of entertainment to satisfy worldly desires. A journalist of the Asahi Shimbun visited Jūnisō five years later. He left us a vivid description of these early changes:6

The grounds are so densely covered with old pine trees and cryptomeria that their branches interlock and throw shade even during the middle of the day, creating a cool breeze that sweeps over the pond. Along the pond, locally known as Jaga-ike, stand several teahouses.

…

Until recently, these teahouses were a place for local grannies to earn a little spending money, and the buildings looked very rustic and informal. However, since around Meiji 20 (1887) this has changed drastically and they are now like the teahouses in Kameido. In the past only a little green tea, edamame (green soybeans), and boiled eggs were served. Visitors brought their own food and drinks.

Now, as the area is becoming more prosperous, development shows its impact. The natural shape of the first waterfall basin has been destroyed, and objects like cast-metal toad figures have been attached to the mouths of the falls, making the place feel staggeringly profane.

Asahi Shimbun, August 13, 1890

The first waterfall refers to Kogane Taki, introduced in Part 2. The journalist then describes the newly built teahouses and the women that work there. He seems to very subtly suggest that they may offer more than just food and drinks.

At the teahouses, there are three or four young women wearing matching hitoe (unlined kimono). As soon as they see customers, they compete in drawing them in, calling out, “have a seat, have a seat!” Their appearance is almost like that of the young women at archery ranges (shooting galleries that often served as a front for prostitution).

When guests arrive at a teahouse, a space of about three tatami mats is partitioned off for one group exclusively. One is immediately served tea and flattery, the rest is left up to the customer.

When asking what is available, one is told, “unagi don (eel bowl), sushi, Western liquor, ramune (lemonade), higashi (dried sweets), fruit, edamame, boiled eggs,” and the like. Even though the service is not yet pushy, that is bound to happen within two to three years.

Customers who want to take a shower under the waterfall can borrow a yukata (simple summer kimono). Those desiring to take a nap are lend a pillow made of a brick with paper wrapped around it.

There’s no need to fear sleeping on a brick pillow. If you can endure the pain to your neck for a little while, you’ll start to love its simplicity. It is delightful to doze off in the cool breeze while listening to the rustling of the pine trees and the sound of the waterfall.

Asahi Shimbun, August 13, 1890

Farewell Tea Fields

Even as the Asahi Shimbun published the above article, an issue that would bring far more dramatic changes to the area had already been brewing for decades. Once again it was about the need for clean drinking water.

The Tamagawa and Kanda Josui served Tokyo well. But as the city grew, the open canals for drinking water were turning into sewers. An official report from around 1873 (Meiji 6) described how the overflow from rain-flooded streets washed “rotten matter, and even the excretions of oxen, horses, dogs, and cats” into the Tamagawa Josui. It also reported “decayed dead bodies of dogs and cats, and sometimes even rotten human corpses” flowing in the josui. Kanda Josui had similar issues.7

Tokyo’s drinking water became increasingly unsafe as Japan’s newly opened ports, and the country’s military adventures abroad, brought in contagious diseases. From the 1850s on, deadly cholera epidemics regularly ravaged Japan.

In 1875 (Meiji 8), Dutch civil engineer Cornelis Johannes van Doorn (1837–1906), employed by the Ministry of the Interior as a foreign advisor, submitted a design to improve Tokyo’s waterworks and solve these and other problems.8 However, little happened until the cholera epidemic of 1886 (Meiji 19) killed almost 10,000 people in Tokyo.9 Nationwide 109,000 people died.10

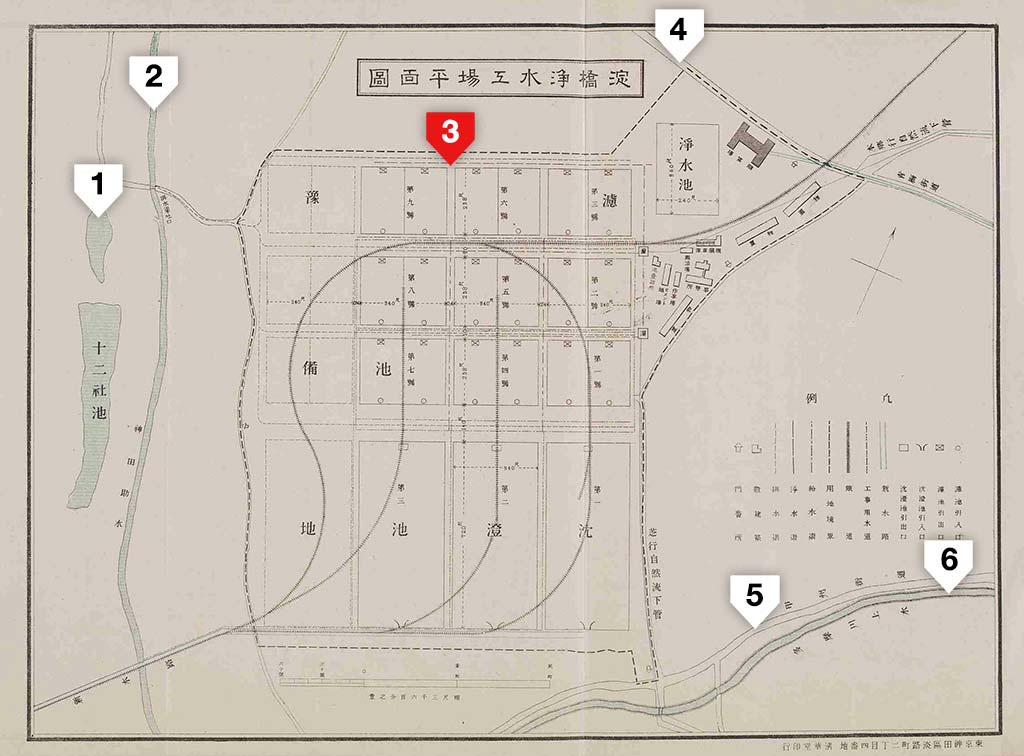

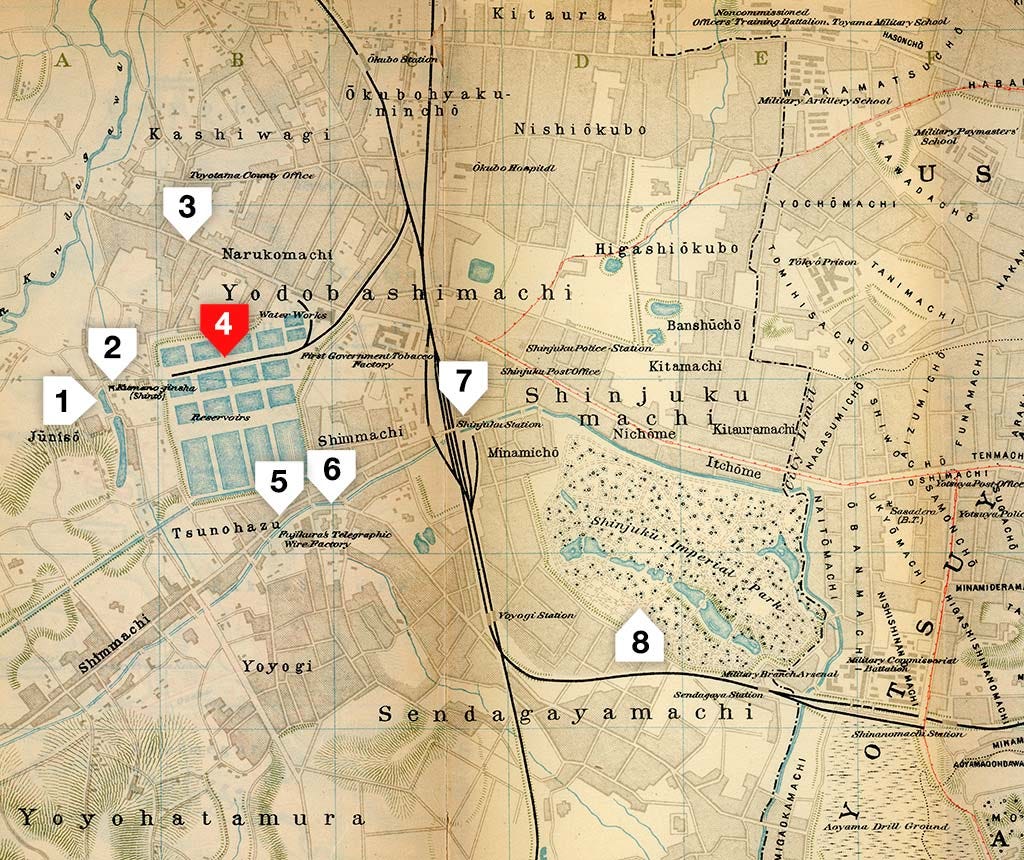

This epidemic shocked Japan’s leaders so deeply that the waterworks plan was finally implemented. In 1898 (Meiji 31), Tokyo’s first water treatment facility was opened in Tsunohazu, which had been renamed Yodobashi in 1889 (Meiji 22).

The Yodobashi Water Purification Plant—built east of Kumano Shrine—totally transformed the area. The large tea fields were razed, the section of the josuibori next to the shrine went underground, and the main waterfall was destroyed.

In his novel Time Passes On novelist Katai Tayama describes how the area looked after it was cleared for construction:11

Here and there, you could see cypress and kaya trees that had not yet been cleared away. The area was not hilly, but it was high in some places and low in others. In the distance you could see the dense forest of Jūnisō, which used to be hidden by forests and bamboo groves.

Katai Tayama, Time Passes On (1916)

Tayama based the protagonist, Ryota, on the experiences of his uncle-in-law, Ryota Yokota (横田良太). The excerpt below is therefore likely very close to what many villagers of Tsunohazu felt after it became known that the government would purchase their land:12

Ryota returned home, but the sadness of having to leave the land he had been so close to for so many years rose up in his heart. The farmland, the tea fields, the forests, the trees, the bamboo groves. They were his sole comfort, his business, and his hiding place.

It was in the shadows of the trees, the forests, the bamboo groves, where he opened his heart when all hope seemed lost, where he lamented the loss of all his savings from years of hard work when the bank went bankrupt, and where he found solace in the grief of losing his daughter. Every blade of grass, every tree felt intimate to him. And yet…

Katai Tayama, Time Passes On (1916)

The purification plant gave birth to rapid urbanization. Initially, open fields surrounded it on three sides, while the Ōme Kaidō was still a narrow road used by few people. Only in the morning and evening was it crowded, as an endless stream of carts carried night soil from city homes to nearby farms using it as fertilizer.13

All this soon changed. Previously cheap agricultural land sold at high prices, turning farmers into landowners. Farms were torn down, fields were razed, town houses popped up like mushrooms. As the above map shows, within a decade and a half most of the Yodobashi area had been built up—although Jūnisō was still rural.

Once again, Tayama’s Time Passes On is our trusty guide. In this passage Ryota reflects in utter astonishment at how thoroughly the area around him had been transformed since his nephew Mayumi moved there some years earlier:14

The world constantly changed. Since the time Mayumi moved here, it seemed as if yet another era had passed. Huge factory chimneys dreadfully spewing out dirty smoke, roads widened for streetcars, newly constructed two-story houses. Who could imagine that there had once been an island here, a forest, bamboo baskets, a water mill? Who could imagine that at this place a Tokiwazu shamisen master had once lived, a young couple committed love suicide, carts passed lonely through dark streets?

Everywhere, Ryoya saw the new era swirling in a vortex of fresh colors. Wherever he went, the land was divided into small sections, fences were built, gates were erected, and stylish two-story houses were constructed. Along the banks of rivers, in the shade of forests, in the hollows of fields, everywhere elegant houses were built and wide shopping streets were constructed.

The farmers of the past were unrecognizable and living respectable lives as landowners. They no longer tilled the land. They wore soft comfortable clothes and spent their days enjoying themselves. Some even became village or county council members, strutting around in haori and hakama.

Homes had become surprisingly elegant. There was a new structure built entirely of cypress wood, with a large stone gate, and a garden decorated with sacred architecture. Wondering whose residence it was, it turned out to be the home of Jinbei, a farmer whom Ryota had looked after in the past.

Katai Tayama, Time Passes On (1916)

Worldly Desires

Even the venerated Jūnisō Pond could not withstand these enormous societal and economic pressures. From the early 1900s on, the natural sanctuary where “worldly desires vanish” was unashamedly converted into a built-up place of entertainment to satisfy worldly desires.

Continue to Part 5 : Worldly desires and the commercialization of Jūnisō.

Notes

斎藤誠治 (1984)『江戸時代の都市人口』地域開発 (240, 1984-09), 東京 : 日本地域開発センター, 61.

『十ニ社に手入れして遊園地に復活』(1885-06-27) in『新聞集成明治編年史 第六卷』東京日日新聞, 105.

「南豐島郡角筈新町の十二社熊野權現の境内を、春來粧飾して舊觀に復せんと計畫ある旨は前號に記せしが、堂宇其他の修理も師になり、玉川上水の流れを引きたる飛泉は、舊に倍する水勢となり、其池畔には花菖蒲を多植付け、茶店三四戸、洋酒店二戸を設けたれば、避暑には適當の遊園となれりとか。」

ibid.

ibid.

『十二社の瀧』(1885-08-23) in『新聞集成明治編年史 第六卷』讀賣新聞, 138.

「十二社の瀧 ○ 同所は近年敗頽せしまゝ修繕も加へねば隨つて遊客も少なく寥々たる景況なりしが今年は瀧壺を始め周圍と修繕を加へ頗る淸潔になしたる爲め、遊客頓かに加して掛茶屋などは手廻りかねるにどなりと。」

『十二所の瀧』(1890-08-13) 朝日新聞.

「同境内は古松老杉鬱蒼として枝を交え午天も尚は日の影を洩らさず涼気の起こる處る一面の大池あり土俗蛇ケ池というこの池に沿うて掛茶屋数軒ありここぞ即ち周荘連の本遽とする所なりツイ近年までは此の掛茶屋も土地の老婆さんの小遣取り位いにてすこぶる鄙朴のんきなる体裁なりしが去る廿年頃より掛茶屋の体裁ぐらりと變りて怡かも亀戸の掛茶屋を見る如くになり其の以前までは僅かに渋茶枝豆ゆで玉子あるのみなればここに遊ぶ人瓢をたずさえ割籠を持参せし由なるが今は追々繁昌するに従い年々にわるく開けて第一瀧つぼとも天然の形を毀ちて例の瀧の口を作りな尚はまた之れに鋳物の蟾蜍など添えてあり俗もまた甚はだし掛茶屋には揃いの単衣など着たる新如三四人づつ居りて客を見れば奪い合ってお掛けなさい、お掛なさいと呼び込む体殆んど揚弓場の姉さんに異ならず客いづれの掛茶屋へ至るも畳三帖ばかりの場所を仕切りて一組の貸切りとなし直ちに世辭と煎茶とを呈して其の他は客の随意に任す何があると問えば鰻の丼、鮨、洋酒、ラムネ、干菓子、水菓子、枝豆、ゆで玉子の類ありと答う然れども未だ無理進めするほどには至らずもそれも二、三年の内なるべし、客の瀧を浴びんとするのもへは浴衣を貸しまた昼寝を試みんとするものへは煉化石を紙もて貼たる枕を貸す煉化一片の夢は石の枕の恐ろしさには似ず少しく領の痛さに堪えればかえって其の素朴愛すべく松の聲瀧の音を聞き涼風の下に一睡を貪ぼる愉快思ふべきなり」

There is a legend that a woman drowned herself at Jūnisō and became a giant serpent. The pond was therefore known as Jaga-ike (蛇ヶ岳, Serpent Pond).

『東京都水道史』115-6ページ所収の奥村陟(Okumura Noboru)の調査報告。『日本水道史 各論編 1 北海道 東北 関東』日本水道協会 (1967).

Kosuge, Nobuhiko (1981). The development of waterworks in Japan. Tokyo: The United Nations University, 21.

Jun, S. (2022). How Disasters Made the Modern City of Tokyo. Journal of Urban History, 48(5), 1008.

Johnston, William (2014). The Shifting Epistemological Foundations of Cholera Control in Japan (1822-1900). Extrême-Orient Extrême-Occident, 37, 171-196.

田山花袋(大正5)『時は過ぎゆく』東京:新潮社, 257.

ibid, 250.

川本三郎 (2003)『ツッジの間だった大久保』in『郊外の文学』東京:新潮社, 62–62.

田山花袋(1952)『時は過ぎゆく』東京:岩波文庫, 338.

「世は絶えず移り變りつ、あつた。眞弓が移轉して来た時から見ると、更にまた一時代過ぎ去ったやうに思はれた。大きな工場の煙突、凄じく湧くやうに漲り上る煤煙、電車が出来るので良く 取りひろげられた通り、新しく建築された二階屋。誰が昔此處に島があり、林があり、竹籃があり、 水車小屋があつたと想像するものがあらう。また誰が昔此處に常磐津の三味線の師匠が住み、男 女の若い二人の心中があり、闇の通りをさびしく荷車が通ったと想像するものがあらう。到る處 に、新しい時代が新しい色彩と巴渦を巻いてゐるのを良太は見た。 何處に行っても、地面が小さく仕切られて、垣が出来て、門が立って、雨洒な二階屋などがつくられてゐた。川の畔、林の蔭、谷地の窪、さういふ所まで、皆な立派な家屋が建ち大きな買い道路が出来た。

昔の百姓達も地主として見違へるやうな立派な生活をしてゐた。かれ等はもう土地などを耕してはゐなかつた。やはらか物などを着て、ぶら/くとして毎日遊んで暮した。あるものは、村會 議員や郡會議員になって、羽織袴で体に乗り廻したりなどした。住宅なども驚くほど立派になっ た。檜木づくめの新しい建築、大きな石の門、敗奇を霊した庭、何處の大家の邸かと思ふと、そ れは昔良太が世話をしてやった百姓の甚兵衛の住宅であった。」

The character Mayumi Okada (岡田眞弓) represents the author himself.

That first photo with the samurai really sets the stage for this episode of the story. Makes you wonder what they were talking about.

The changes people had to make and the losses suffered from disease outbreaks brought forth some real innovation.

This was the beginning of the time when sericulture started to flourish and great wealth was created due to silk exports.

In Tayama’s “Time Passes on”, which I quote a lot in this essay, some characters lament the incomprehensible changes and how hard life has become. It must have been a terribly difficult and confusing time to live through.

But it did indeed also create opportunities and boundless innovation, especially to the silk industry which paid for Japan’s massive transformation.