Spotlight • Empire of Color (4)

How 19th century Japanese artists mastered the art of hand colored photography — Why Japan became the empire of hand colored photography.

Read on the site | Comment | Support

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4

Around the World in 80 Days

Photography was practiced across the globe, and skilled artists existed everywhere. So why did hand coloring reach such exquisite levels in Japan, and why have so many of these photographs survived?

One could attribute it to a quirk of history, or perhaps the law of cause and effect. Seemingly random historical events—occurring just in the right order and at the right time—created conditions that unleashed the extraordinary development of hand-colored photography in Japan.

The most significant of these events was the opening of Japan. After more than two centuries of self-imposed isolation, Japan opened its borders to foreign trade in 1859 (Ansei 6). Until then, a small number of Dutch traders had been the only Westerners allowed to enter Japan, and they had been confined to the tiny island of Dejima in Nagasaki.

The opening caused a sensation in Western nations. Over the following decades, an ever-increasing number of Japanese goods appeared on the shelves of shops. Galleries were filled with Japanese woodblock prints and other artworks. There were special exhibitions, even recreated Japanese villages.

The wave of imports launched Japonisme and influenced exciting new movements in the arts and architecture. The refreshingly new Japanese aesthetic inspired the likes of Vincent van Gogh, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt, James McNeill Whistler, Frank Lloyd Wright.

The admiration for all things Japanese was boundless. Many imagined a traditional and harmonious culture with natural landscapes untouched by industrialization and modernization. Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) expressed this idealized vision in a letter he wrote to his brother Theo in 1888 (Meiji 21):1

If we study Japanese art, we see a man who is undoubtedly wise, philosophic and Intelligent, who spends his time how? In studying the distance between the earth and the moon? No. In studying the policy of Bismarck? No. He studies a single blade of grass.

But this blade of grass leads him to draw every plant and then the seasons, the wide aspects of the countryside, then animals, then the human figure. So he passes his life, and life is too short to do the whole.

Come now. Isn’t it almost an actual religion which these simple Japanese teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers?

And you cannot study Japanese art, It seems to me, without becoming much gayer and happier, and we must return to nature in spite of our education and our work in a world of convention.

Vincent van Gogh, 1888

An ever growing fascination with this newly discovered and seemingly unspoiled civilization had been ignited. Japan was ultra-cool.

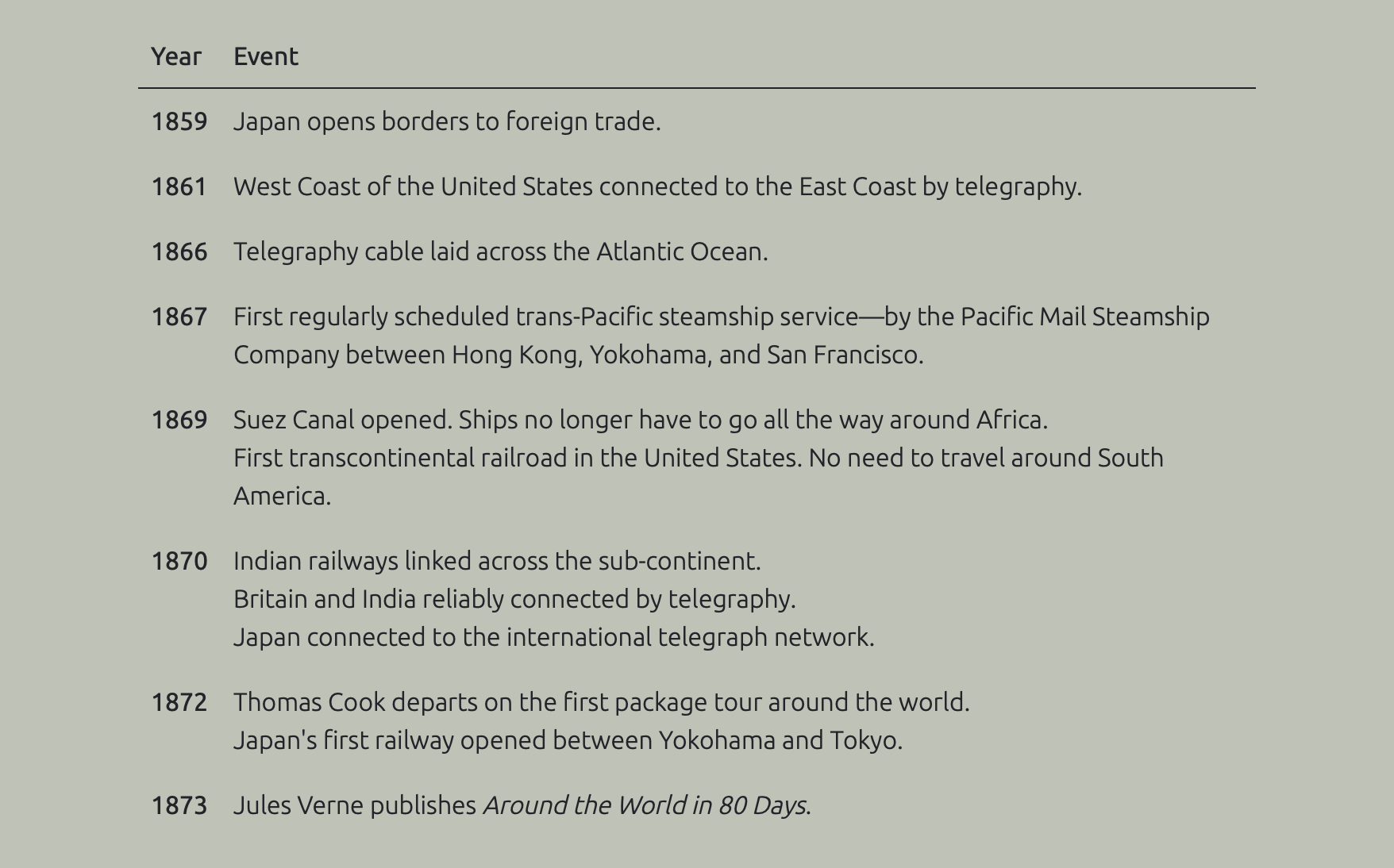

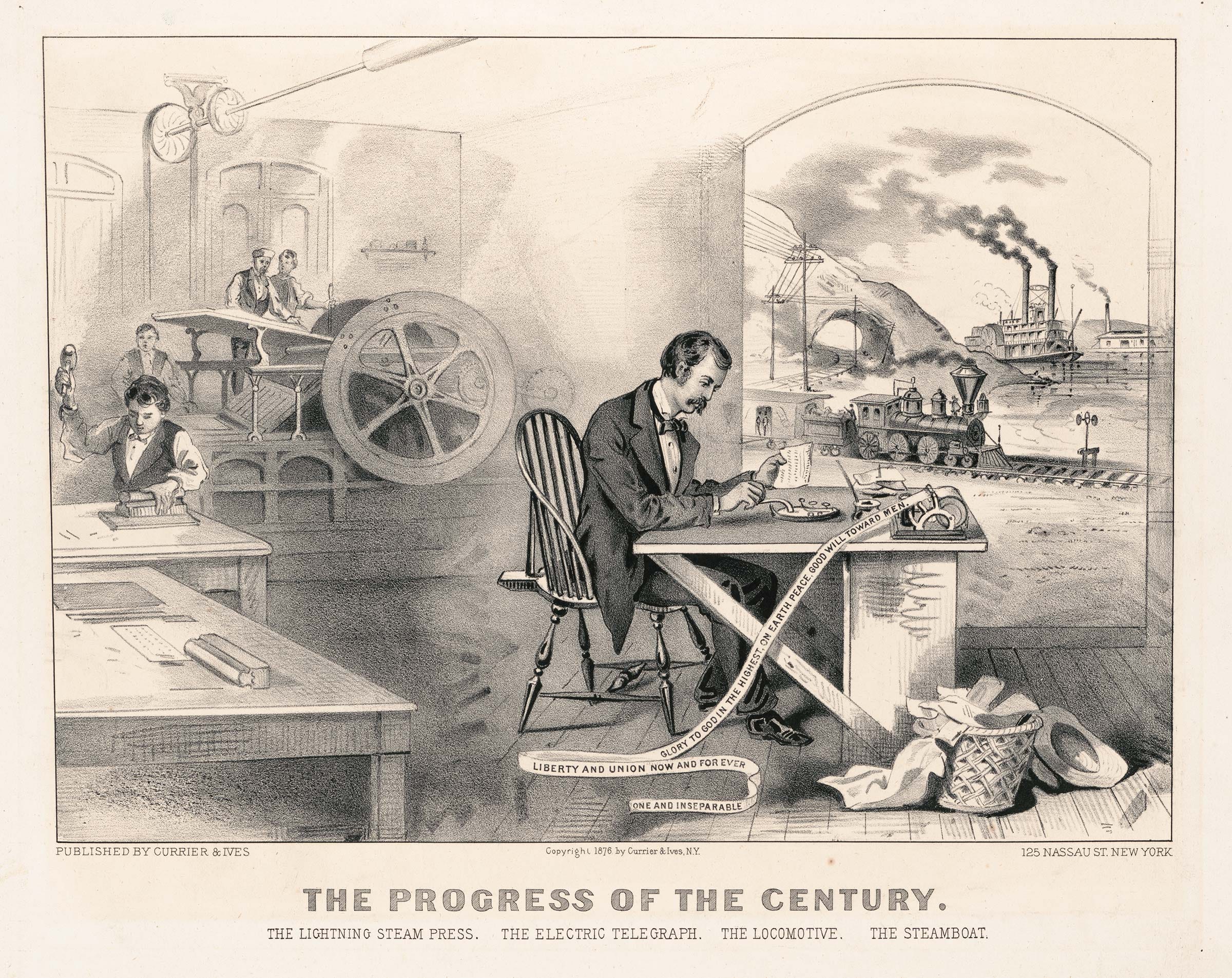

It may have been cool, it was also far away and incredibly hard and costly to reach. A cascade of technological innovations was about to change this dramatically. Only a decade after Japan opened its doors, telegraphy, steamships, and trains had completely transformed global travel and trade. Suddenly Japan was within reach.

It is hard to overstate this transformation. When Japan opened its borders in 1859 it took over four months to exchange letters with Britain, then the commercial center of the world. After Japan was linked to the global telegraphy network in 1870 (Meiji 3) responses could be received within hours.

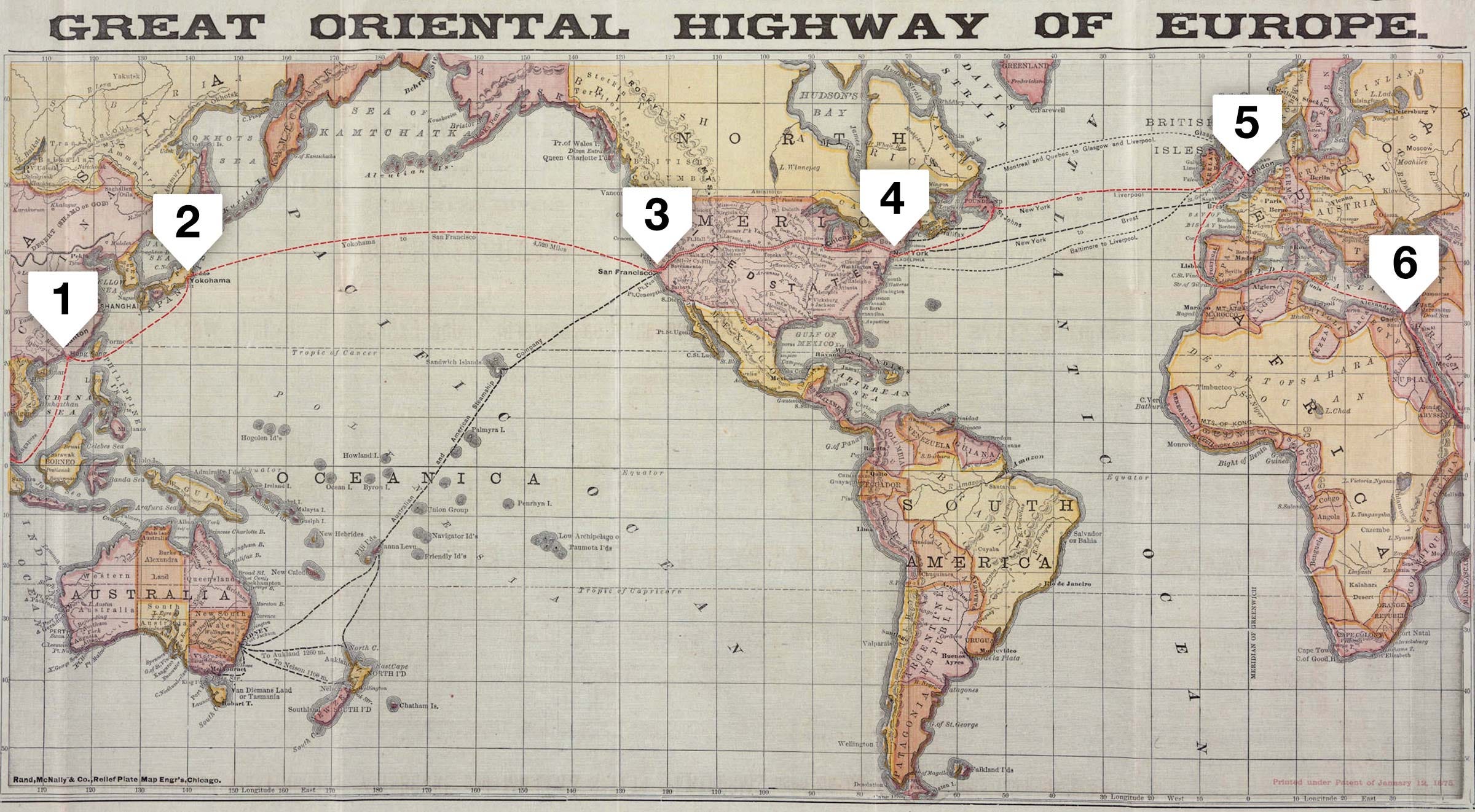

The impact of steamships and trains, and the opening of the Suez Canal and the trans-American railroad in 1869 (Meiji 2), was just as great. Travel time between Japan and the West was reduced from many months to several weeks.

The 1872 (Meiji 5) edition of Disturnell’s Railroad and Steamship Guide could barely conceal astonishment at the drastic transformation that had taken place:2

A traveller or business man who, a few years ago, went to San Francisco, Japan, China or India, or made the circuit of the globe, arranged his affairs with the expectation that at least a year or two of his life was required to make the journey by land and water. To-day he can start from New York or London, transact important business, and enjoy the pleasures of travel, returning to his home, if desired, within the period of three months; during which time he is in communication with the chief centres of business by telegraph and steam post-routes.

Disturnell’s Railroad and Steamship Guide, 1872

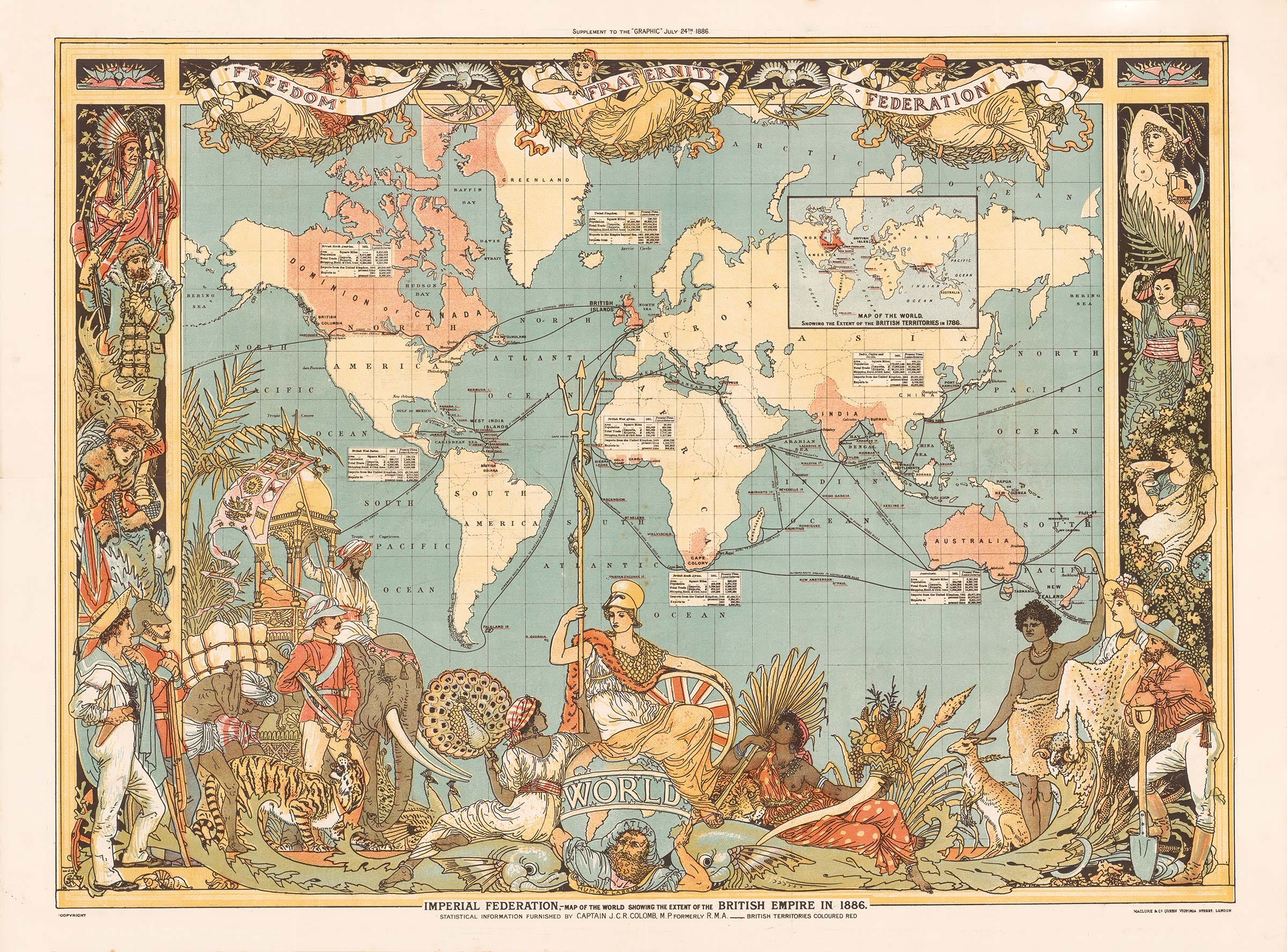

All these changes took place just as British power was at its peak. Great Britain acting as the global policeman had ushered in an era of relative stability, making international travel safer than it had ever been.

British travel entrepreneur Thomas Cook (1808-1892) was one of many who saw the opportunities of this global transformation. In 1872, he led the first-ever package tour around the globe, dramatically showcasing this brave new world.

Cook had barely returned when French author Jules Verne (1828–1905) published Around the World in 80 Days. The book became an international bestseller and put the idea of a trip around the world in the heads of people who had previously never even imagined it.

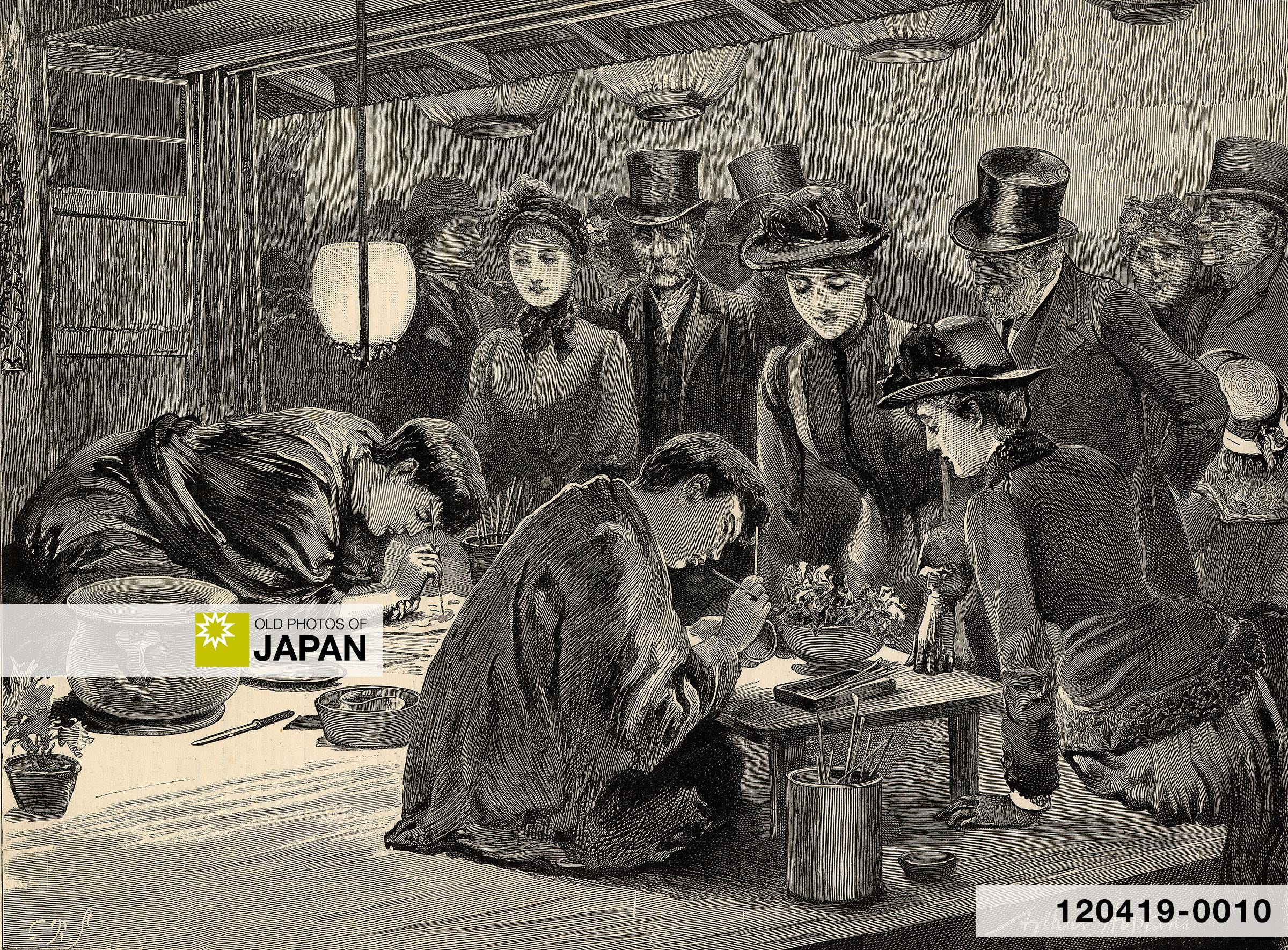

The age of the globetrotter had begun. For the first time in history large numbers of tourists started traveling around the world. Japan was on the top of the list of these new world travelers. Everybody wanted to see this entrancing fairytale land. And they all wanted memorable souvenirs.

New Markets

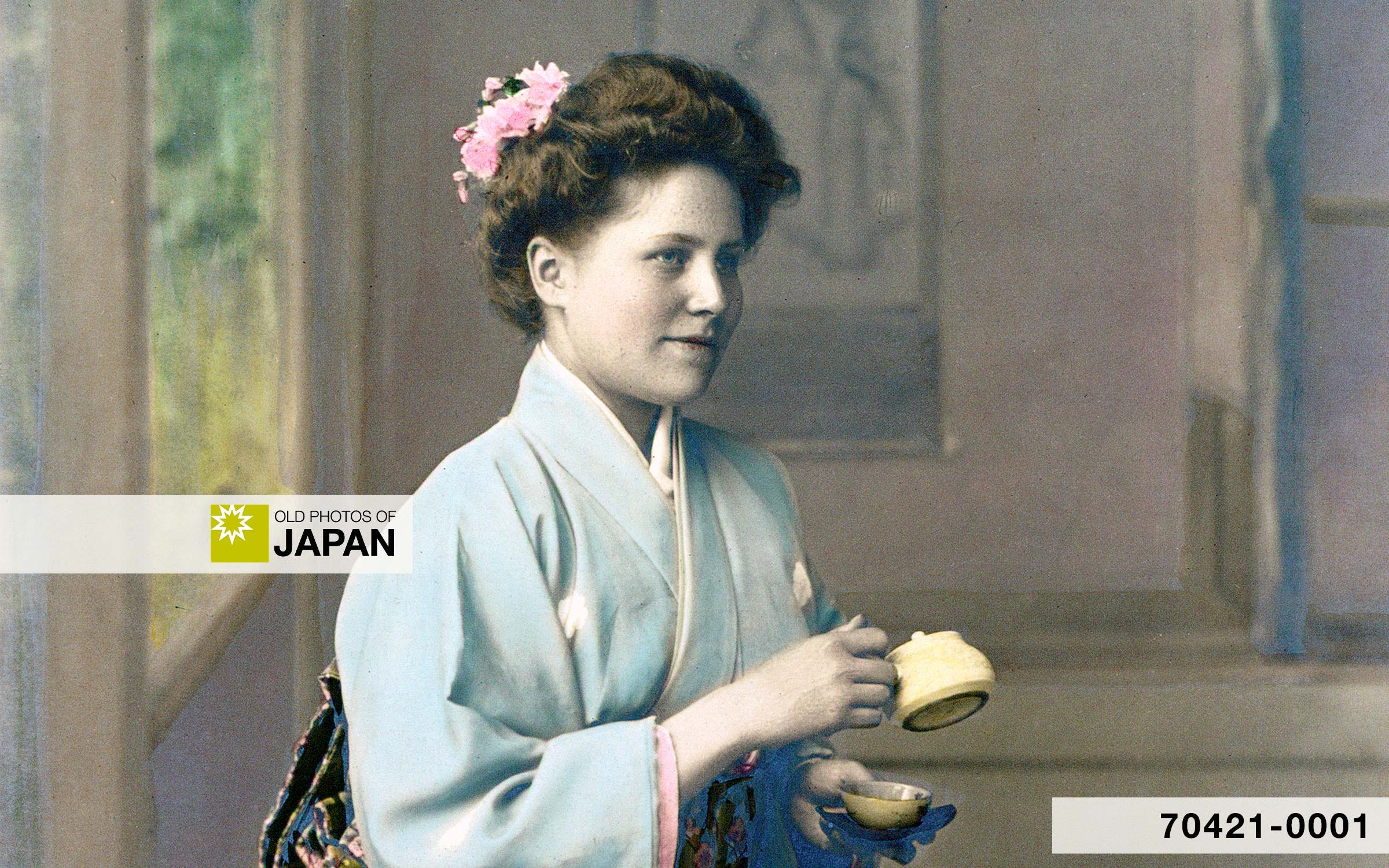

When Beato first started out in Yokohama in 1863 his customers were mainly foreign residents: merchants, missionaries, military officers, diplomats. The ever increasing number of globetrotters that started to visit Japan from the 1870s, opened up a completely new and exceptionally lucrative photography market: lavish albums with souvenir photos, as well as studio portraits in Japanese clothing.

These albums did not only function as souvenirs, but also as gifts between international associates—upscale corporate gifts inscribed with dedications.3

Business was not limited to Japan. People who could not afford to travel to Japan were just as fascinated by the country and a thriving export market developed. The same steamboats and trains that brought the globetrotters made it possible to transport the photographs relatively quickly and affordably from Japan to markets on the other side of the world.

The result was an intensely enterprising and competitive photographic industry catering to a seemingly insatiable global market. It allowed hundreds of traditionally trained Japanese artists to develop their photo coloring skills to heights unequaled in other countries.

This professional souvenir photograph market reached its peak during the 1890s after which it started to collapse. One cause was Eastman Kodak‘s popular compact and portable film camera which allowed visitors to take their own photos. Another was new printing technology that gave birth to mass-produced low-cost postcards.

At first these were also hand colored, but in the 1920s color increasingly vanished. Monochromatic photographs and postcards became the norm. The age of hand colored photography came to an end and the once so popular Yokohama studios disappeared forever.

Today, more than a century later, large numbers of these beautifully hand colored photographs still pop up in auctions. While countless numbers of photos in Japan itself were destroyed by earthquakes, fires, war, or the humid climate, the souvenir photographs survived.

They survived precisely because they were souvenirs. They were taken abroad and preserved as valuable personal memories in well-protected, sturdy, and often expensive albums that were cherished and cared for.

Postscript — Legacy

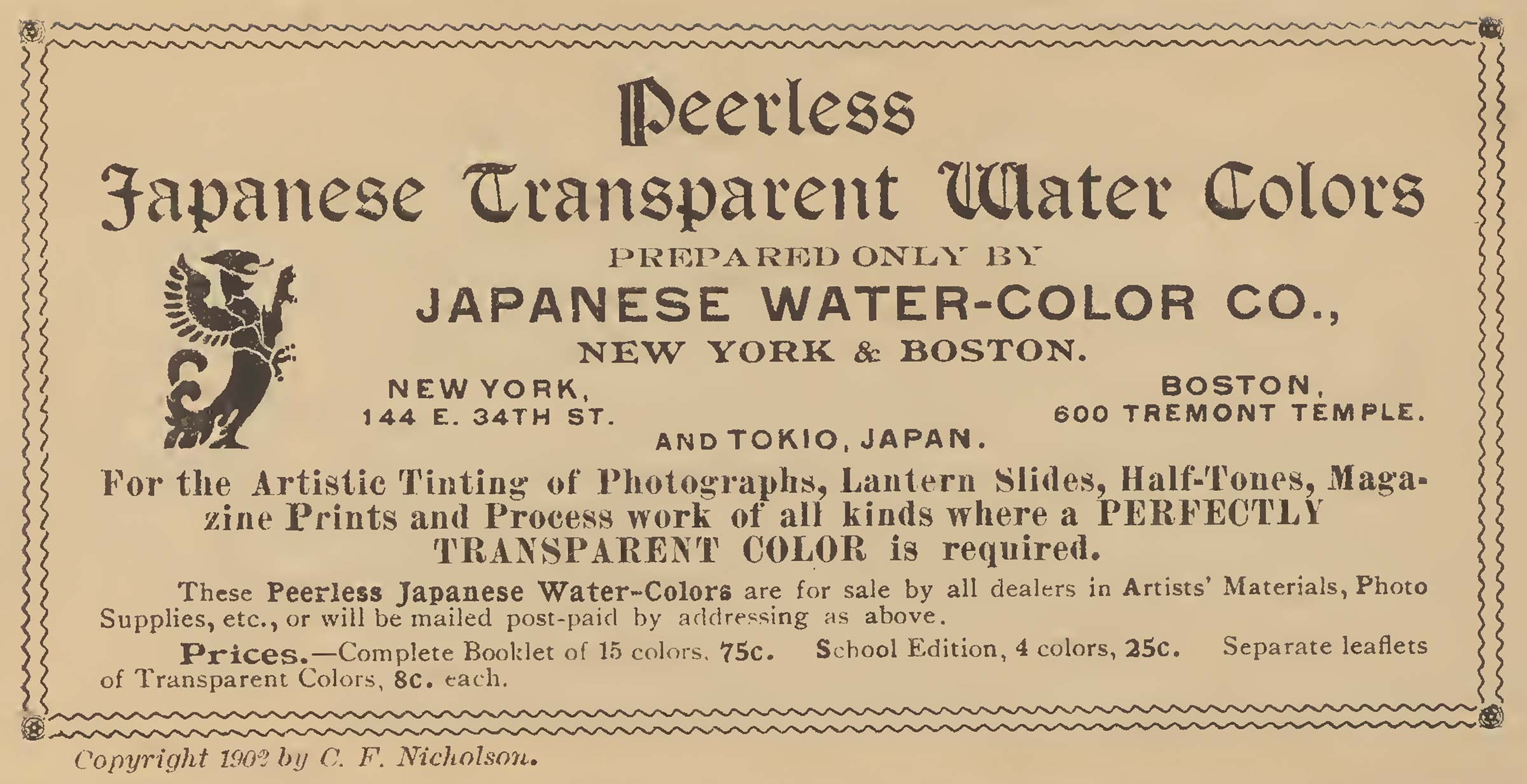

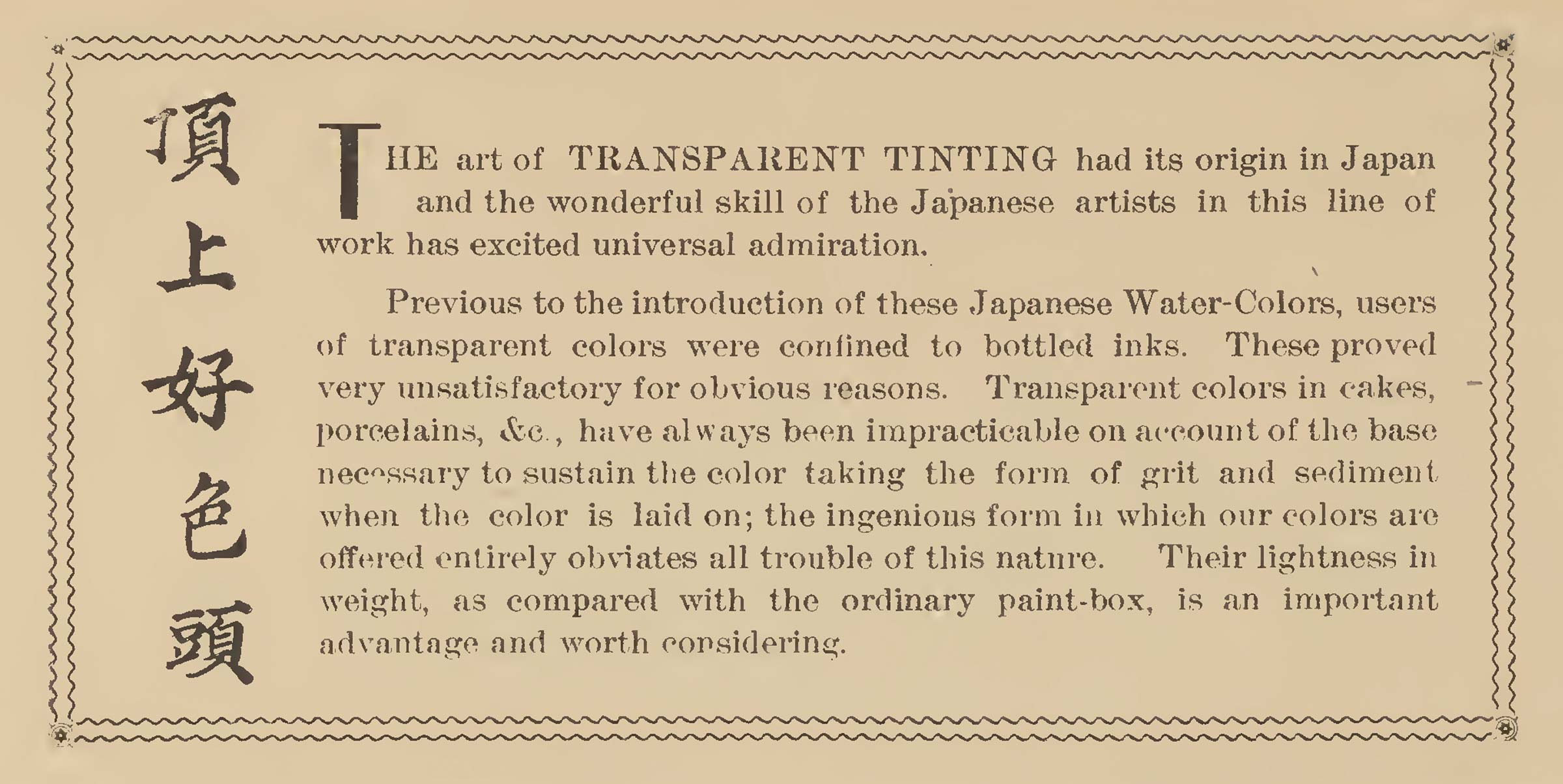

Amazingly, there is a small living legacy of these 19th century hand colored photographs from Japan. Ever since Boston-based publisher J.B. Millet printed the multi-volume Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese in 1896 (Meiji 29) with hundreds of thousands of photographs hand colored by Japanese artisans, Americans associated top-class hand coloring unequivocally with Japan.

This persuaded a New York and Boston based company to brand their water colors Peerless Japanese Transparent Water Colors.4 The product’s instructional text stated that “the art of transparent tinting had its origin in Japan and the wonderful skill of the Japanese artists in this line of work has excited universal admiration.”

The product is still produced today, and is much loved by artists. The word Japanese however is no longer part of the name.

Appendices

Notes

Roskill, Mark (1967). The letters of Vincent Van Gogh. New York: Atheneum, 295.

Disturnell’s Railroad and Steamship Guide: Around the World in Ninety Days, by Rail and Steam (1872). Philadelphia: W.B. Zieber, 113.

Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 205.

Lehmann, Ann-Sophie (2015). The Transparency of Color: Aesthetics, Materials, and Practices of Hand Coloring Photographs between Rochester and Yokohama. Getty Research Journal No. 7, 81-96. Retrieved on 2023-03-25.