PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7

This article is a supplement to the essay Shinjuku’s Lost Paradise about the history of Jūnisō Pond and Nishi-Shinjuku.

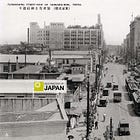

From July 30 through November 19 we explored the extraordinary story of Jūnisō Pond—a pond lost to history—in what is today the famed skyscraper district of Tokyo’s Nishi-Shinjuku.

We covered over four centuries in seven articles, each one brimming with extremely rare images. Quite a few of those images were actually so rare that even people who study the history of Nishi-Shinjuku had never seen them before.

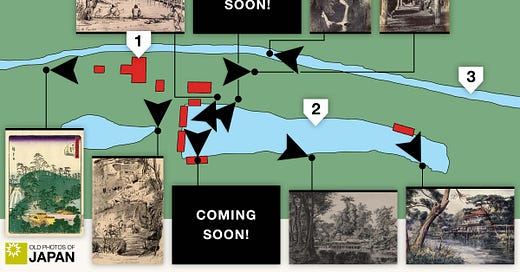

Because the images are so important to the story, I have created a visual chronology with the images superimposed on custom-made maps.

Finding original documentation to make these maps historically accurate was exceptionally challenging, and took me to several museums, libraries and archives. Based on the available information they are as accurate as they can possibly be.

About this Chronology

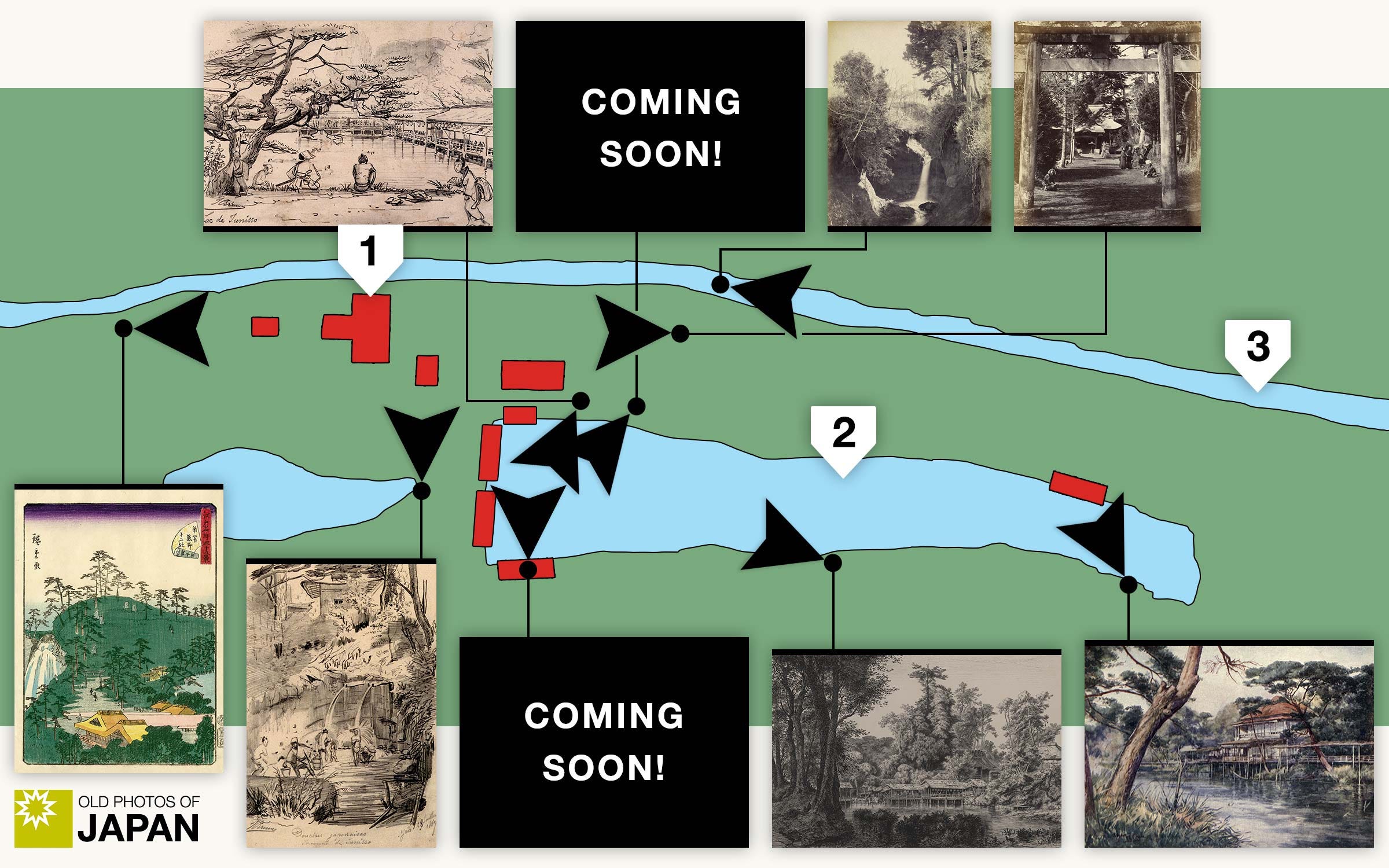

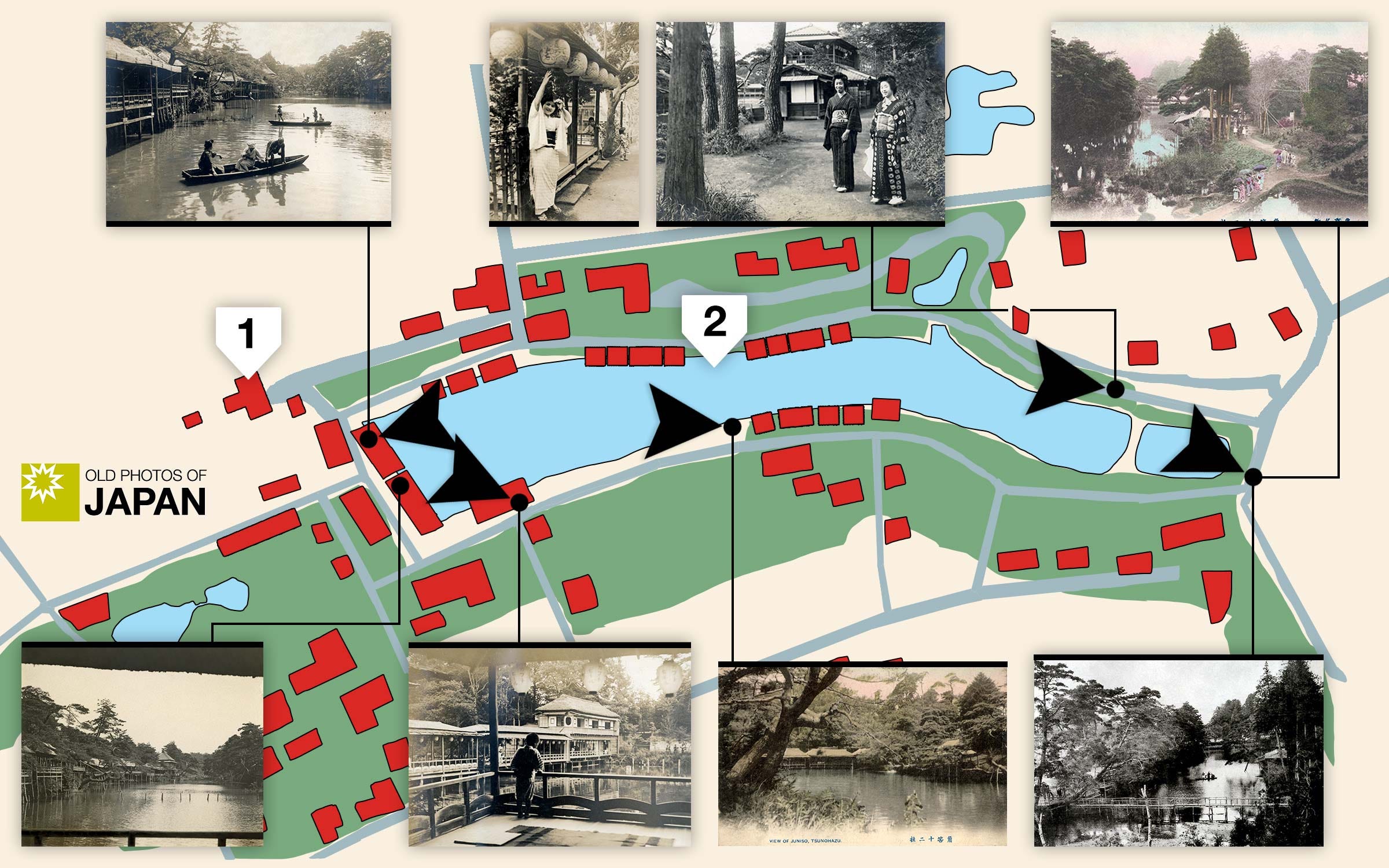

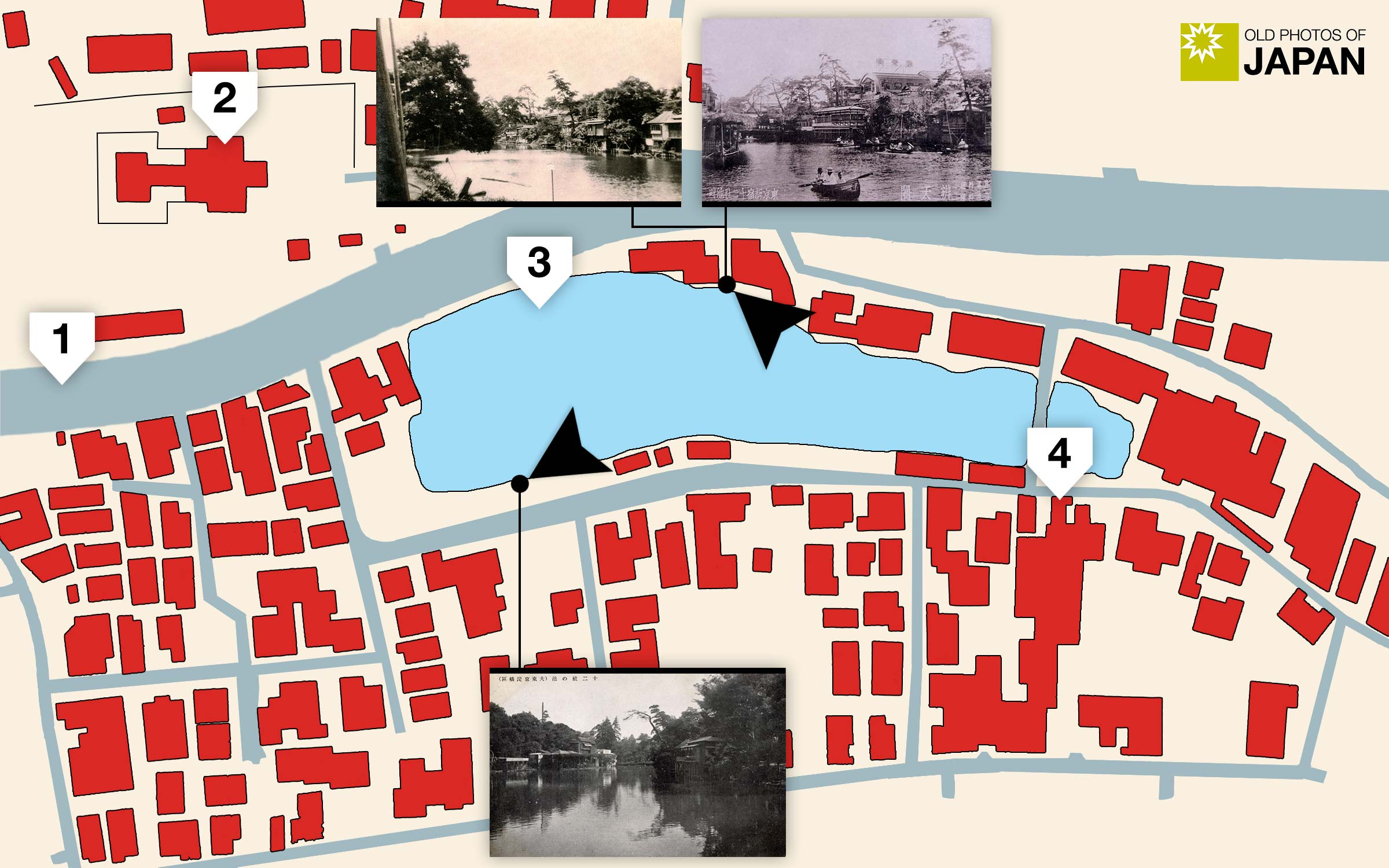

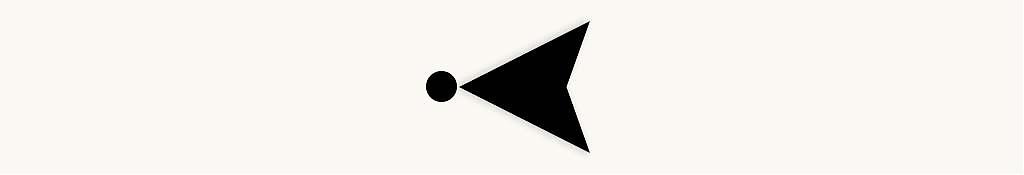

I have created maps for Jūnisō in the 1800s, 1900s–1910s, and 1930s. The likely location where the artist stood when photographing or sketching is represented with a dot on the map. An indented triangle represents the direction of the view to the subject shown in the image. The indented part points to the subject. Like this:

Each map is based on historical maps and other data. The locations in the images have been determined by meticulously comparing the images with each other as well as maps, including ones not published in the essay.

Note that the map is from a specific year, but the images on that map are from a range of years. So the situation on the map does not always fully agree with the situation shown in the images.

The left side of each map points north. The maps are approximate and not in the same scale. So, even though the pond looks smaller in an earlier map, it was actually larger. The pond shrank as it was filled in to construct buildings and roads.

On the official Old Photos of Japan site you can also see a slideshow below each map with large versions of the images. The slideshow includes the dates of the images and the names of the artists.

Unfortunately, it was impossible to recreate the slideshows in the newsletter. I highly recommend visiting the official site!

1. Jūnisō in the 1800s

Natural Retreat

In the 1700s, Jūnisō became famous for its pond and waterfalls, clustered around a small thatched shrine known as Kumano Jūnisō Gongen. Jūnisō experienced the peak of its popularity in the first half of the 1800s. In 1851 (Kaei 4), Buddhist monk Fukyū Dōjin described Jūnisō as an almost sacred natural sanctuary where “worldly desires vanish”. The first innocent step towards Jūnisō’s commercialization started with renovations in 1885 (Meiji 18).

I found three unknown (and unidentified) photos of Jūnisō from the 1860s. This discovery will be announced soon. Two are in the map, marked COMING SOON. They will be unveiled after the announcement. No photos of the pond before 1900 were believed to exist.

This period is described in PARTS 1 through 4.

2. Jūnisō in the 1900s–1910s

Nature to Nightlife

Jūnisō ‘s commercialization as a playground started after Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). The shoreline was lined with teahouses and entertainment features were added, such as a fishing pond, an archery range, and a public flower garden. Meanwhile, Shinjuku became Tokyo’s most important railway hub, while Yodobashi’s population exploded. By the 1920s, Jūnisō Pond was no longer remote, nor rural.

This section features five previously unknown photos of Jūnisō, all in the Duits Collection. In the slideshow on the official site they are marked with a star.

This period is described in PARTS 5 and 6.

3. Jūnisō in the 1930s

Popular Geisha District

In 1924 (Taisho 13) Jūnisō became an official hanamachi with 32 machiai and 27 geisha houses. By the mid-1930s it had become a great success. At the height of its popularity there were nearly 100 restaurants and machiai, and some 300 geisha. This period ended in 1944 (Showa 19) when the government ordered restaurants, teahouses, geisha houses, cafes, and bars to close for business.

This period is described in PART 7.

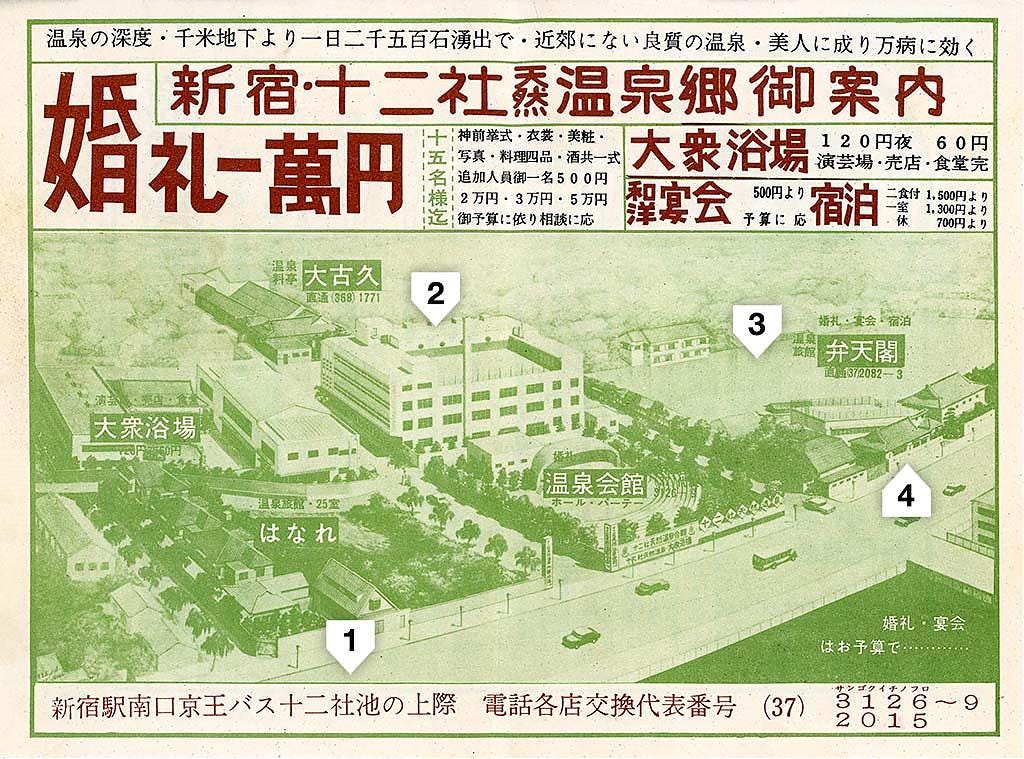

4. Post-WWII Jūnisō

Farewell

After the end of WWII, Jūnisō's hanamachi was rebuilt on a smaller scale. It briefly flourished, culminating in 1958 (Showa 33) when a hot spring was excavated and opened as Jūnisō Onsen. In 1968 (Showa 43) Jūnisō Pond was filled in.

This period is also described in PART 7.

Jūnisō in Japanese Art

During the last eight decades of the Edo Period (1603–1868) Jūnisō inspired several acclaimed Japanese artists—including giants Hokusai and Utagawa—to create woodblock prints. A slideshow of a selection of these artworks can be seen on the official Old Photos of Japan site.

The official site also features a timeline of the pond’s history, as well as the credits for the maps and images.

★ New Discovery

The discovery of the images of Jūnisō from the 1860s will be announced soon!

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

How exciting to find photos never before identified of Juni’s pond. A great discovery. Looking forward to this! Great research as always!

Thank you for all your research!!