Crossing Japan's 'Raging Rivers'

You will never look at the famed Tōkaidō highway again in the same way.

Hi, I am Kjeld Duits and I created Old Photos of Japan.

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for daily life in old Japan. I track down and acquire rare vintage prints and research and conserve them.

If you value or enjoy this work, please help support it!

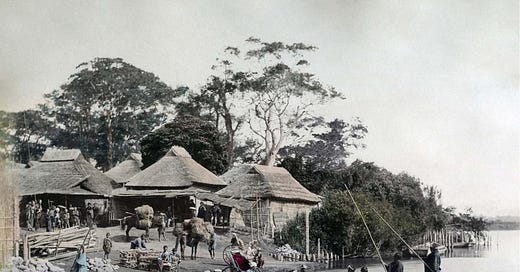

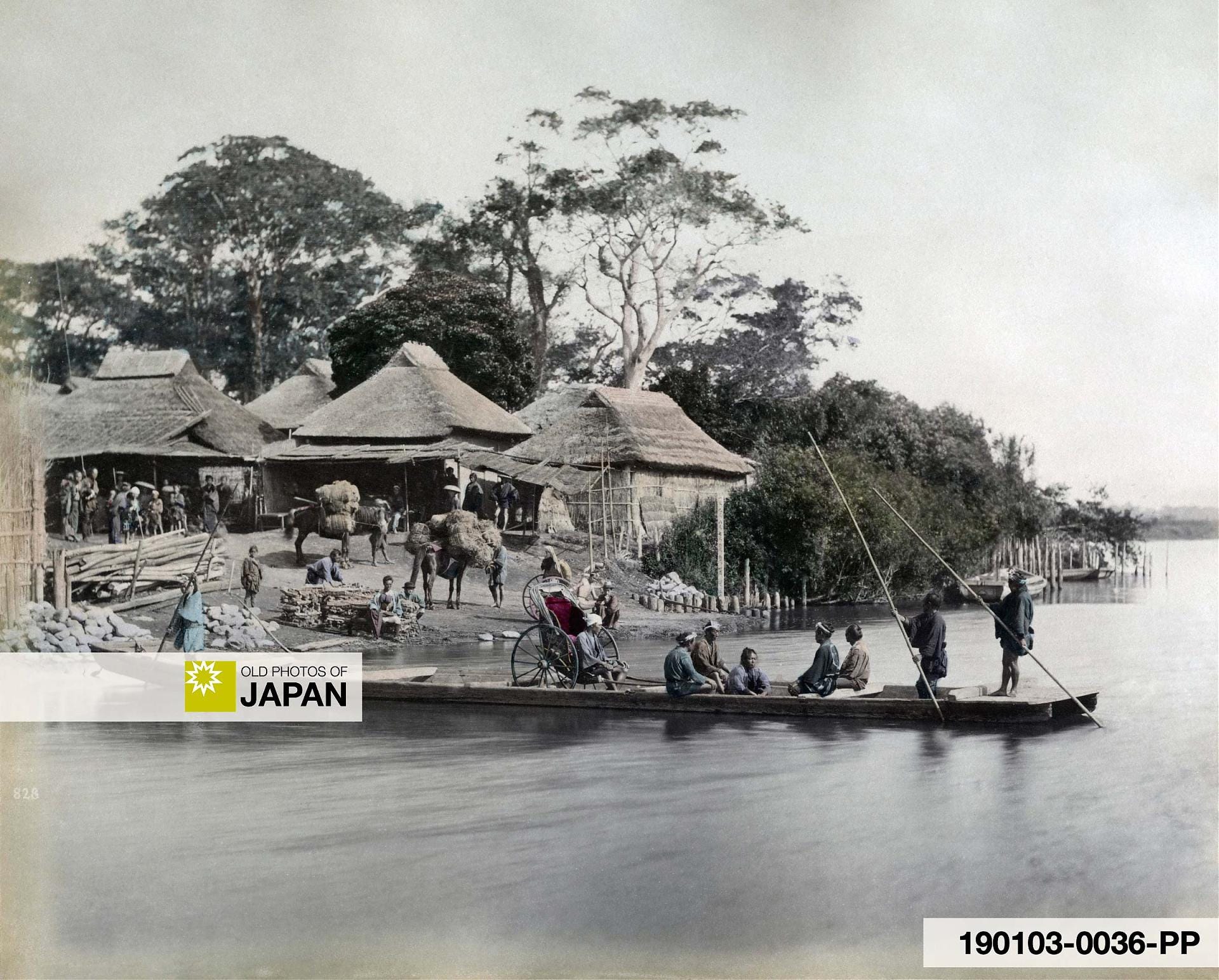

Three boatmen transport passengers and a rickshaw on the famed ferry at Kawasaki, the second station on the Tōkaidō. Although this scene is peaceful, river crossings rightfully terrified travelers in old Japan.

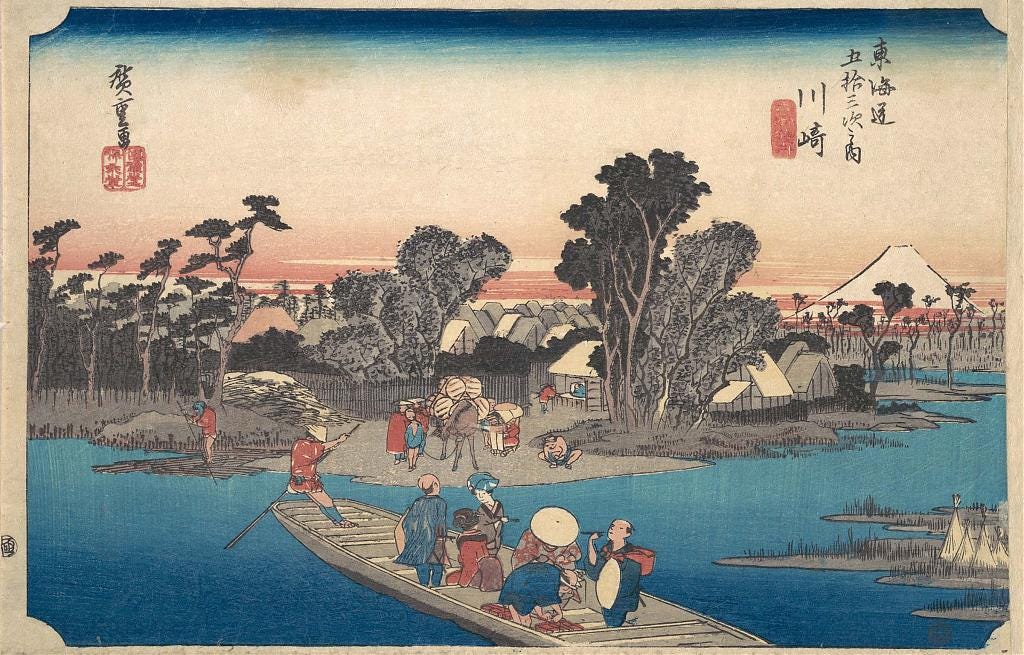

Even if you have never seen this photograph before, you are probably familiar with this scene of a ferry on the Tōkaidō. Japanese ukiyoe artist Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川広重, 1797–1858) immortalized it in his series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (東海道五十三次, Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi), which was based on his trip along the Tōkaidō in 1832 (Tenpō 3).

In the early 1870s, Italian–British photographer Felice Beato (1832–1909) went to the exact same spot at Kawasaki and shot the photograph above. As you can see in Hiroshige’s print below, very little had changed in the intervening four decades.

Until railways were built in the late 1800s, travelers ran into river crossings like this one across the Tamagawa River everywhere. The Tamagawa alone had some 27 crossing sites. The Kawasaki crossing however was the busiest, accounting for about 70 percent of all goods and people going in and out of Edo.1

Mountains and Rivers

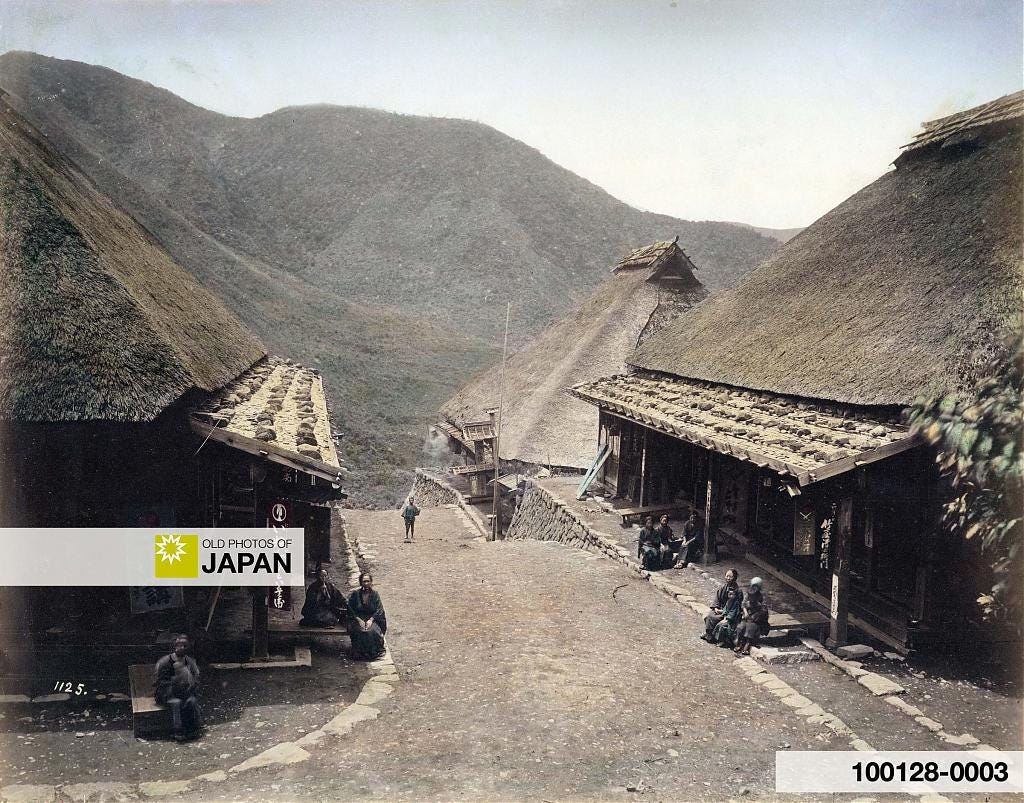

Vintage photos and woodblock prints make this way of traveling look romantic and attractive. But travel in old Japan could be physically demanding to the extreme. No wheeled vehicles were used, while horses could only be ridden by people of high status. Travelers went either on foot or by sea.

Because of the great dangers of sea travel most people walked. An athletic feat considering that a roundtrip on the popular Tōkaidō was over 1,000 kilometers.

Japan’s mountainous topography is not kind to people traveling on foot. The country is essentially a colossal long and narrow mountain range popping out of the Pacific Ocean that feeds over 35,000 rivers.2 A traveler had to either climb steep mountain passes or cross the many rivers flowing from the mountains to the coast. Especially the Tōkaidō had a large number of major water crossings.

On a map Japan’s rivers appear short and puny. But looks deceive. It is exactly the short distance that makes them dangerous. For example, the Tamagawa descends from 1,900 to 100 meters within a mere 90 kilometers.3

This can create incredibly fast and powerful flows with vast differences between normal volume and that during heavy rainfall. The maximum discharge of the Mississippi is three times the normal one. For the Tonegawa River, which flows through the heavily populated Kantō Plain, it is one hundred times.4

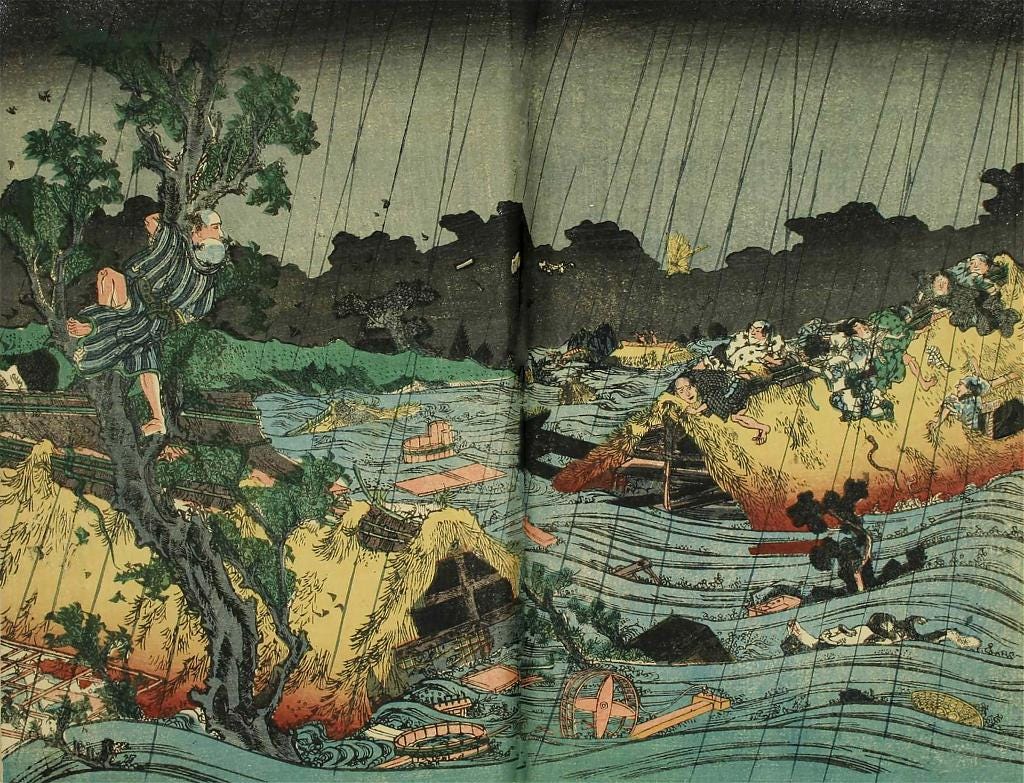

Heavy rain regularly turned Japan’s short rivers into violent monsters. Some had such strong and treacherous currents that ferries or bridges were impossible.

During the 1600s a bridge across the Tamagawa at Kawasaki washed out seven times.5 After the seventh time in 1688 (Jōkyō 5) the government gave up on building a new one and decided to rely on the ferry shown in the top photo.

A bridge was built again in 1868 (Meiji 1). This one was soon washed away too. Kawasaki finally got a permanent ferro-concrete bridge in 1925 (Taisho 14).6

The furious flow of Japan’s rivers did not only prevent bridges, it also determined the design of landing places. Look again at the photos and woodblock print above and you will notice the lack of docks and piers for boarding the ferries. Like the bridges they would be swept away.7

A river landing was at best reinforced with an embankment of stepping stones. Many landings, as at Kawasaki, were just sandy or rocky strips. Planners were often forced to adapt to their environment instead of transforming it.

The design of the river landings in turn determined the design of the ferries. As you can see in the earlier photos and woodblock prints, many featured square ramps for easily getting on and off board at the simple landings. To avoid grounding they were flat-bottomed and had shallow draft.

German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716), who lived in Japan from 1690 through 1692, noticed that the ferries had flexible hulls.8

These [ferries] are built to suit local conditions, with flat, thin hulls so they can bend when gliding over protruding rocks and simply be freed from the rocks without danger.

Engelbert Kaempfer

The River Runs Wild

The Japanese were painfully aware of how life-threatening their rivers were and that they required respect. Authorities closed the river for traffic when water levels rose above a certain height.

This forced travellers to wait and stay at inns in the stations near the river until it could be crossed again. Often the wait lasted for just a few days to a week. But occasionally it could take many weeks.

In 1868 (Keio 4) the important Ōigawa River crossing in what is today Shizuoka Prefecture was closed for 28 days. Some travelers ran out of money, while others secretly crossed the river by themselves. Many died in the attempt.9

One traveler who would not wait when ordered was the Japanese painter and Rangaku scholar Shiba Kōkan (司馬江漢, 1747–1818). He left us his account of what he saw when he pushed on during a flood near Kyoto during a trip on the Tōkaidō in the late 1700s. Officials at Kusatsu Station were stopping all travelers, but Shiba, assisted by a guide, circumvented them by walking through the fields:10

The water was so high it reached my thighs. I pushed on, testing the depths with my walking stick. Sometimes it was deeper, sometimes, shallower. I informed the people behind in a loud voice and we barely made it to Ubagamochi. From there it was a solid road. Eight or nine houses along the front road from the tonya [official transport manager] had been swept away. Along the back road, there were many more, and forty to fifty people had drowned. They piled up the corpses in heaps.

This was not all. At Moriyama, Hikone also, the floods swept away houses and caused people to drown. The man who carried my luggage, told me he had been clinging to an overhang but the water carried him away about ten cho into the second floor of a friend’s house. He climbed out at once and saved his life, he said.

[ 10 chō = ±1.1km. ]

Shiba Kōkan

Japanese travelers were not the only ones ignoring official instructions. Nineteenth-century English travel-writer Isabella Lucy Bird (1831-1904), who in 1887 (Meiji 20) travelled deep into Japan’s heartland, was skeptical when warned not to travel on.

She quickly discovered that ignoring those warnings put her life in danger—her book Unbeaten Tracks features several extremely perilous river crossings. During one such crossing in Akita Prefecture she, and her guide and interpretor Ito, helplessly looked on as a boatman drowned.11

Just in the nick of time we discerned a punt drifting down the river on the opposite side, where it brought up, and landed a man, and Ito and two others yelled, howled, and waved so lustily as to attract its notice, and to my joy an answering yell came across the roar and rush of the river. The torrent was so strong that the boatmen had to pole up on that side for half a mile, and in about three-quarters of an hour they reached our side.

They were returning to Kotsunagi—the very place I wished to reach—but, though only 2 1/2 miles off, the distance took nearly four hours of the hardest work I ever saw done by men. Every moment I expected to see them rupture blood vessels or tendons. All their muscles quivered. It is a mighty river, and was from eight to twelve feet deep, and whirling down in muddy eddies; and often with their utmost efforts in poling, when it seemed as if poles or backs must break, the boat hung trembling and stationary for three or four minutes at a time.

Isabella Lucy Bird, Unbeaten Tracks in Japan (1888)

They eventually reached a spot where the river was joined by another making the water rush and roar ever wilder. Then something terrible happened.

I had long been watching a large house-boat far above us on the other side, which was being poled by desperate efforts by ten men. At that point she must have been half a mile off, when the stream overpowered the crew and in no time she swung round and came drifting wildly down and across the river, broadside on to us. We could not stir against the current, and had large trees on our immediate left, and for a moment it was a question whether she would not smash us to atoms.

Ito was livid with fear; his white, appalled face struck me as ludicrous, for I had no other thought than the imminent peril of the large boat with her freight of helpless families, when, just as she was within two feet of us, she struck a stem and glanced off. Then her crew grappled a headless trunk and got their hawser [thick mooring rope] round it, and eight of them, one behind the other, hung on to it, when it suddenly snapped, seven fell backwards, and the forward one went overboard to be no more seen. Some house that night was desolate.

Isabella Lucy Bird, Unbeaten Tracks in Japan (1888)

Keep Fighting

Travel is a lot safer and far more comfortable today. This has however come at a cost. Modern engineering and urbanization have wrapped Japan’s rivers in concrete. Many are hidden away behind vast levees and even underground—more than 100 rivers and canals flow beneath Tokyo alone.

Nonetheless, the rivers themselves regularly remind us that Japan is still a country of rivers. It continues to struggle with torrential rains—disastrous floods and mudslides are common.

As a Japan Correspondent I covered Japan’s natural disasters for three decades and was repeatedly deeply impressed by the remarkable resilience of the Japanese.

In 2018 I covered the aftermath of heavy rain in southwestern Japan that caused over 270 deaths and great destruction. In a village devastated by mudslides I interviewed a Japanese architect in front of his damaged home. Surrounded by death and destruction he was philosophical. Japan’s very strength lay in its numerous disasters, he told me:

There are so many disasters in Japan, we are always busy thinking how to cope with them. That is the source of Japanese technology. It also teaches you to never give up, to always keep fighting.

Yoichi Sato, Architect

DID YOU ENJOY THIS?

Help me research and save Japan’s visual heritage of everyday life.

SUPPORT OLD PHOTOS OF JAPAN | BUY AN ART PRINT

Notes

Steele, William M. (2000). The History of the Tama River: Water and Rocks in Modern Japanese Economic Growth. Asian Cultural Studies 26, 48.

よくある質問とその回答(FAQ) 国土交通省 Retrieved on 2024-01-23.

Wilson, Roderick I. (2021). Turbulent Streams: An Environmental History of Japan’s Rivers, 1600–1930. Leiden, Boston: BRILL, 61.

Rivers in Japan. River Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, 6. Retrieved on 2024-01-23.

The Tonegawa was appropriately known as one of the top three “raging rivers” of Japan (日本三大暴れ川, Nihon Sandai Aberagawa).

At the time the Tamagawa River had several names. Around Kawasaki it was known as the Rokugōgawa River.

Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos (1995). Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan. Harvard East Asia Monographs, 52.

Steele, William M. (2000). The History of the Tama River: Water and Rocks in Modern Japanese Economic Growth. Asian Cultural Studies 26, 47–48:

The 218 meter bridge was originally built in 1600. Repeatedly damaged by floodwaters, “it was repaired in 1612 and 1643, washed out and rebuilt in 1646, 1659, and again in 1670. Floods destroyed the bridge in 1671 and again in 1672; again it was rebuilt but damaged and repaired in 1684; washed out in 1686, repaired, but destroyed again in 1688.”

Damian, Michelle M. (2010). Archaeology through Art: Japanese Vernacular Craft in Late Edo-Period Woodblock Prints, 210.

Kaempfer, Engelbert; Bodart-Bailey, Beatrice M. (1999) Kaempfer’s Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 249–250.

東海道【川を渡る道】 国土交通省 中部地方整備局 浜松河川国道事務所 Retrieved on 2024-01-24.

Plutschow, Herbert (2022). A Reader in Edo Period Travel. Folkestone: Global Oriental, 235–236.

Bird, Isabella L. (1888). Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: an Account of Travels on Horseback in the Interior, Including Visits to the Aborigines of Yezo and the Shrine of Nikkō. London: John Murray, 177–178.