The "Human Horses" of the Rickshaw

The rickshaw’s story is one of promise, romance, and pain. Did you know that the rickshaw contributed to Japan driving on the left side of the road?

Read this article on the site | Comment on this article.

Lots of mysteries remain about the first rickshaw. In 1669 (Kanbun 8), Dutch author Arnoldus Montanus published a book about Japan that included a fascinating illustration of an early human powered two-wheeled carriage. However, modern historians have expressed doubts if the members of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), on whose accounts the book was based, did indeed see such a vehicle.

We know for sure that a rickshaw-like vehicle, known as the vinaigrette, was invented in France in the late 17th century. This vehicle has entered art history thanks to a famous painting by French artist Claude Gillot (1673-1722) showing two vinaigrette pullers unwilling to give way. Although the vinaigrette disappeared some time before the revolution, postcards of the vehicle were very popular in France during the early 20th century.

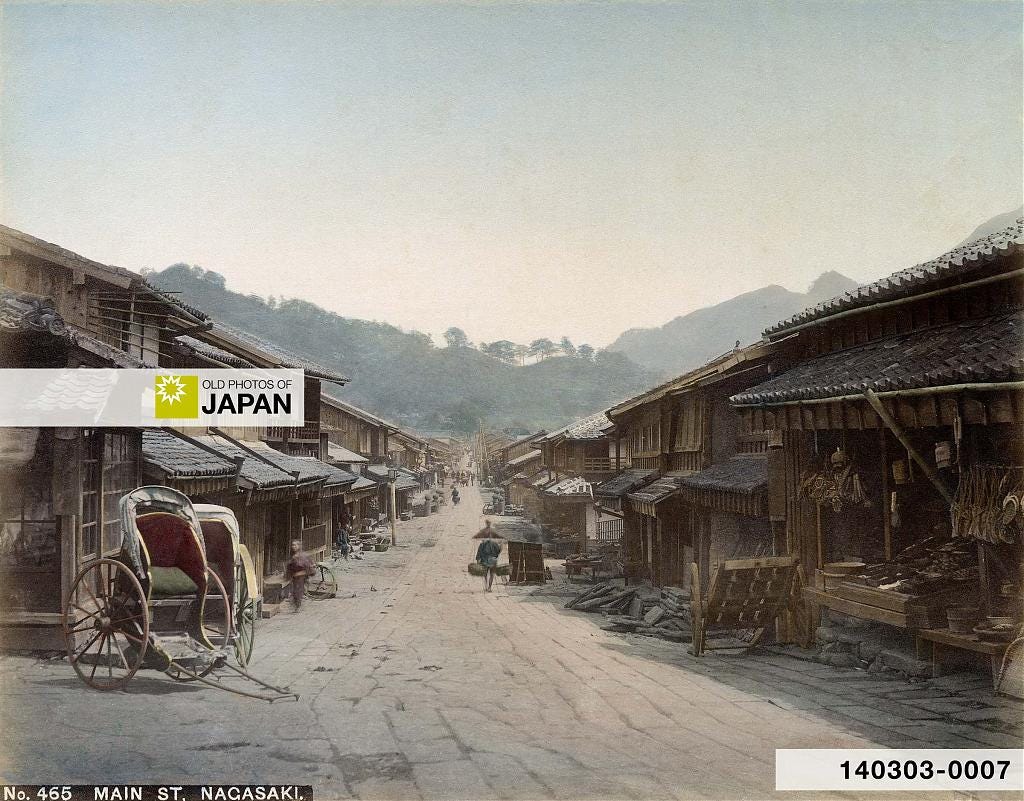

After its re-invention in Japan in the 19th century, and its spread to countless Asian countries, the rickshaw has come to represent Asia. In its modern incarnation of the auto rickshaw, it still rules many Asian roads, as well as many in Africa.

But the rickshaw is now so rare in the country of its reinvention that it evokes feelings of nostalgia. Very much in the same way that a steam locomotive or horse-drawn carriage does. Just like these last two, Japanese rickshaws are now only found at museums and popular sightseeing spots.

The origins of the Japanese rickshaw are a bit unsure. Two accounts are considered to be the most reliable. One story claims that Yokohama-based American Baptist missionary Jonathan Goble (1827–1897) built the first rickshaw when his sick wife Eliza became unable to walk. Another introduces Yosuke Izumi (和泉要助, 1829–1900), Tokujiro Suzuki (鈴木徳次郎, 1827–1881), and Kosuke Takayama (高山幸助), respectively a chef, a greengrocer, and a cartwright in Tokyo, as the originators.

Likely, Goble and the Tokyo trio came up with the idea around the same time. But Izumi and his friends were the first to register the invention. On March 22, 1870 (Meiji 3), they applied to the Tokyo government for a license to manufacture and operate the vehicle, and described it as follows:1

It is a little seat in the Western style, mounted on wheels so that it can be pulled about. It does not shake as much as the usual cart, and it is easy to turn round. It will not hinder other traffic, and since it can be pulled by one person, it is very cheap.

Application to Tokyo Government

They called it a jinsha (人車, human vehicle), but the Tokyo authorities changed the name to an already existing term, jinrikisha (人力車), literally human powered vehicle. In his book Things Japanese, British Japanologist Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850–1935) whimsically explained how over the years the vehicle acquired even more names, including the English term rickshaw:2

The poor word jinrikisha itself suffers many things at the hands of Japanese and foreigners alike. The Japanese generally cut off its tail and call it jinriki, or else they translate the Chinese syllable sha into their own language, and call it kuruma. The English cut off its head and maltreat the vowels, pronouncing it rickshaw.

Basil Hall Chamberlain, Things Japanese (1891), 242

Popularity

The newly invented rickshaw did not take off right away. The trio parked two brand new rickshaws in front of the public noticeboard at Tokyo’s Nihonbashi bridge, probably one of the most visited areas in the city. People crowded around, but nobody took a ride. So Suzuki loaded family members into a rickshaw and pulled them around the neighborhood until people started to hire the rickshaws.3

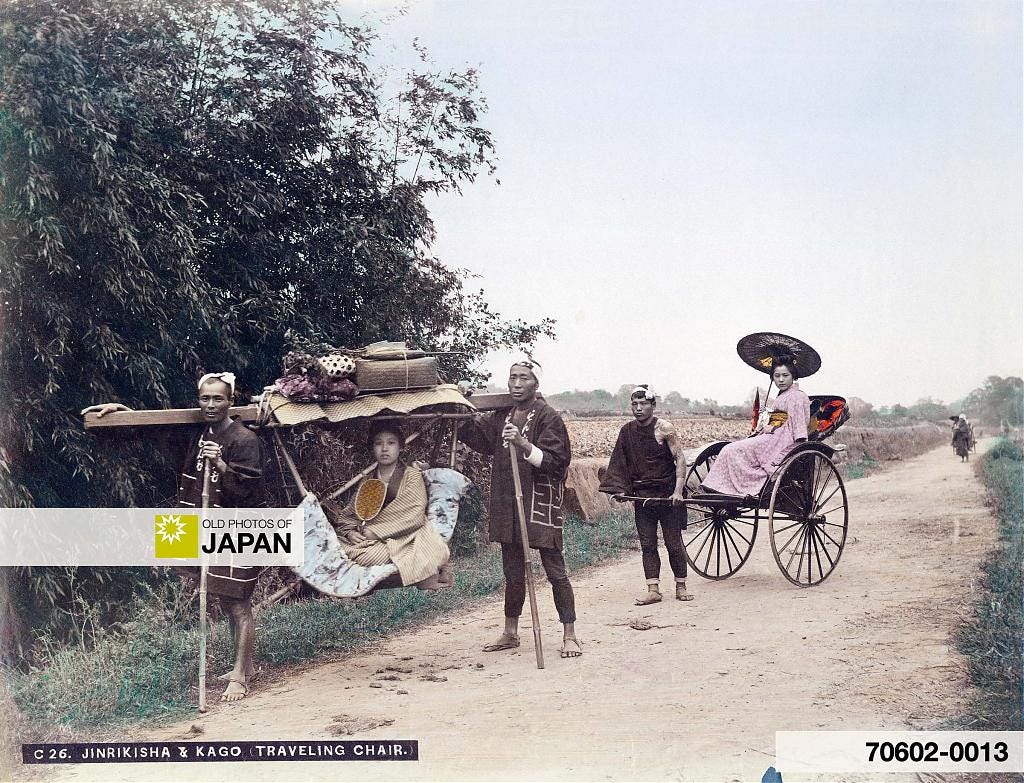

Until then, the kago (palanquin) had been omnipotent in Japan. Understandably, kago bearers felt threatened by the cheaper rides and tried to bully the shafu (車夫, rickshaw pullers, also known as shariki, 車力). But as the rickshaw took off, they gave up and many of them became shafu themselves.

In 1872 (Meiji 5), only two years after the rickshaw was first licensed, there were already some 56,000 rickshas in Tokyo, and over 16,000 in Osaka. In 1883 (Meiji 16), there were almost 167,000 of them nationwide.4 The uncomfortable and cramped kago had virtually disappeared from city streets.

The rickshaw’s explosive popularity was the result of many factors coming together. The strict Edo period (1603-1868) restrictions on movement were being relaxed, the Tokyo government approved the rickshaw on condition of a low fare, it was relatively comfortable and convenient, roads were being improved, horses were expensive, and foreign trade was booming at the treaty ports, which created a need for cheap, fast and reliable transportation.

Even more important, the rickshaw strongly represented Japan’s modernization as expressed by the then enthusiastically embraced term bunmei kaika (文明開化, civilization and enlightenment). It manifested a promise of development and wealth, of going forward fast. Essentially, the timing was perfect for the rickshaw.

Romance

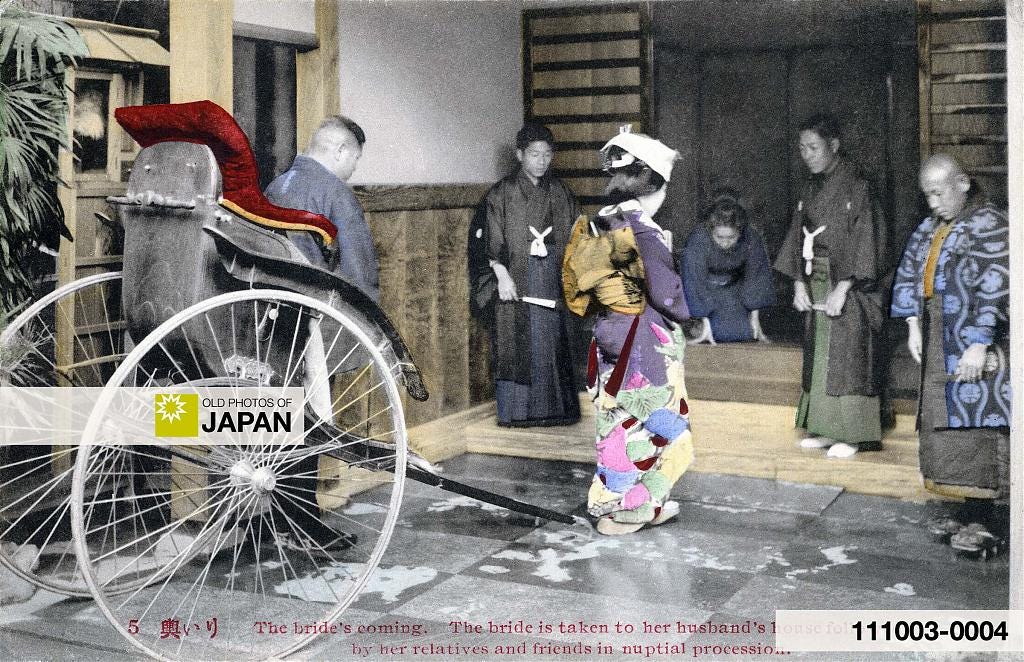

The rickshaw was a simple affair: two wheels, two shafts for the puller to hold on to, often with little bells that tinkled as the shafu ran, a cushioned seat on springs, a receptacle underneath for the belongings of the passengers, and a hood to protect the passengers from rain and sun. A waterproof lap robe made of oiled paper further protected the passengers.

After sunset, a paper lantern bearing the shafu’s name and license number was attached to the shafts, creating a dance of lights on Japan’s streets. American novelist George Waldo Browne wrote that “to see one of them coming in the distance is to imagine one sees a firefly bobbing along the road.”5

This sentiment was echoed by American author and photographer Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore (1856–1928), the first woman to sit on the board of trustees of the National Geographic Society. She described them as “glowworm lights flitting through the streets and country roads in the darkness.”6

In the dark, the shafu warned the passenger and following rickshaws of upcoming crossways and holes in the road. Their cries of warning, repeated by each shafu following behind one after the other, sounded almost musical to the ears of a foreign observer.

In Summer, the shafu initially wore just a loincloth, perfectly adapted to the hot and humid weather and their challenging work. But as Japan grew increasingly sensitive to how it was perceived by the “civilized” West, the shafu were forced to wear to what amounted to a uniform:7

He is usually a spare [healthily lean] person, with muscles well developed, clothed in short blue cotton tights, and overshirt of the same material, with wide-flowing sleeves, and open at the neck. A strip of cotton cloth is worn about the forehead, and, when it is very hot, he covers his head with a wide-rimmed straw hat of prodigious size and shaped like a huge mushroom. Sandals made of straw, with a loop for the great toe, protect his feet from the hard, smooth roads.

George Waldo Browne, The Far East and the New America (1901), 322–323

When it rained, the shafu kicked off these sandals and ran barefoot. To keep his body dry and warm, he relied on the traditional straw rain-coat favored by farmers, or wore an apron and cloak made of oiled paper.

The stout rickshaw men were famous for their stamina and endurance. They managed 8 kilometers (5 miles) an hour easily, between 48 and 64 kilometers (30-40 miles) a day. Some shafu managed 80 to 100 kilometers (50–62 miles) a day.8

German physician Erwin von Bälz (1849–1913), who lived and worked in Japan between 1876 and 1905, recounted an episode about this incredible stamina in his diary. On a trip to Nikko from Tokyo, he needed to change horses six times, while a Japanese person traveling the same route on the same day “was drawn the whole distance by one jinrikisha man.” Even more astonishing to Von Bälz was that the rickshaw arrived in Nikko only half an hour after he did.9

Usually there was just one man per rickshaw—a great improvement over the kago, which needed two. But on hilly terrain, or when the passenger was unusually heavy, a second person would join, to either pull or push.

At first, rickshaws were built in one- and two-passenger versions. The two-passenger version was especially loved by young couples and men escorted by geisha. It allowed the two to talk, and the close proximity encouraged intimacy and romance. Especially when the rickshaw hit an unexpected bump.

The two-seater inspired popular songs like Ainori Horokake (相乗り幌掛け, riding together under the same hood) and Hoppeta Ottsuke (ほっぺたおっつけ, cheek to cheek). But it also inspired handwringing newspaper articles calling for its abolition before it further corrupted the country’s morals.

Scandalized journalists need not have worried. Single-seaters were faster and that mattered more. The ratio of the two variations was about fifty-fifty in the 1890s. But by the start of the Taisho period (1912–1926), only 1 of every 10,000 rickshaws was a double-seater. Modern society’s need for speed and efficiency had won out over romance.10

Size was not the only thing that differentiated early rickshaws from later versions. Initially, the rickshaw was seen as the perfect canvas for creating maki-e (蒔絵), a decoration technique in which designs are created with lacquer on which metal powder such as gold or silver is sprinkled. One observer in 1871, counted 115 different designs on passing rickshaws during just a few hours of observation.11

English traveller and writer Isabella Bird (1831-1904), who travelled through Japan in 1878 (Meiji 11), left us a brief description:12

The body is usually lacquered and decorated according to its owner’s taste. Some show little except polished brass, others are altogether inlaid with shells known as Venus’s ear, and others are gaudily painted with contorted dragons, or groups of peonies, hydrangeas, chrysanthemums, and mythical personages.

Isabella Bird, Unbeaten Tracks in Japan (1905), 5–6

Perhaps, the authorities found them gaudy, too. In 1886 (Meiji 19), new Ministry of Home Affairs regulations required that the body be lacquered in a solid color. Or perhaps this was because the glittery images obscured the license number on the rear. Nonetheless, by 1889 (Meiji 22), maki-e rickshaws had vanished from the streets.13

Human Horses

Westerners, who were long used to horse-drawn carriages, were both fascinated and shocked by the rickshaw men. Many referred to them as “human horses” in their books, letters and diaries. Quite a few expressed discomfort in being hauled around by another human being. But apparently not enough to avoid using their cheap and convenient mode of transportation. Occasionally, the disquiet exposed a disturbing conviction of imperialist superiority.

French industrialist Émile Étienne Guimet (1836–1918), founder of the Guimet Museum in Paris wrote about his discomfort. “One’s first ride in a jinrikisha,” he wrote, “is singularly distressing. One is being pulled by one’s own kind! The terrible weariness brought by each step of the trot. It fills you with a sort of regret.”14

Yet, when the shafu were unable to move fast enough, Guimet expected machinelike invincibility. “Their breathless and weakened [grunts], their bleeding feet and sunken eyes, their shrunken noses and dry mouths made me worry that they would crash in exhaustion and pain.”15

A March 16, 1894 (Meiji 27) editorial by Nagoya based newspaper Miyako Shimbun (都新聞) fiercely ridiculed the hypocrisy of those who spoke of the plight of shafu, yet continued to use their services.16

The man in a tall hat who puffs on an imported cigar as he gaily bowls along in a black jinrikisha throwing up dust sometimes preaches about humanitarianism. He’s usually an American or European in Japan on holiday who travels here and there conveniently and cheaply thanks to the jinrikisha. Back in his own country he says, “The Japanese are a cruel race; they make their fellow man pull a carriage with passenger.” If all men are brothers, he would not so readily ride in a jinrikisha. He’s an outrageous humanitarian! If he thinks that the Japanese are not his brothers because they are a yellow race, he’s a disgraceful humanitarian! In any case, if it is inhumane for one’s fellow man to pull one’s carriage, it is also so for one’s fellow man to row one’s boat or bear one’s kago. But no one makes that absurd argument.

Miyako Shimbun, March 16, 1894

Keeping Left

The rickshaw, in combination with other new transportation modes, gave rise to traffic regulations. Since the early Meiji period (1868–1912), people had been urged to keep to the left, and rickshaws to pass on the left. But the rule was not fixed. Yet by 1874 (Meiji 7), it had become customary for vehicles to use the middle of the road, and for pedestrians to stay on the edges.

This changed in 1906 (Meiji 39) when a new traffic regulation ordered pedestrians to walk on the left. The same regulation barred children less than four years old from walking the streets alone. The regulations also prohibited walking on streetcar tracks, or lanes intended for vehicles, except to cross.

Additionally, the public was asked to be extremely careful when jumping on or off trolleys. Fathers and elder brothers were urged to take care of the young.17

The Japanese didn’t quite confirm to these rules as Jukichi Inouye described in Home Life in Tokyo (1910):18

What with carriages, jinrikisha, waggons, handcarts, and bicycles jostling one another and men, women, and children threading their way through the labyrinth or fleeing before motor or electric cars [streetcars], the more frequented streets of Tokyo present a confused mass of traffic; but in respect of actual numbers they are really less crowded than western streets of similar importance. The busy appearance is mostly due to the absence of sidewalks, and the bustle is increased by the wayfarers having to run to and fro to get out of the way of the vehicles.

In streets provided with sidewalks one would expect less confusion; but as a matter of fact, people are so used to walking among vehicles of all sorts that they prefer sauntering on the carriageway to quietly pacing the sidewalks; and it is no uncommon experience to meet a company walking abreast in the middle of the road and dodging carriages while the sidewalks are almost deserted.

Jukichi Inouye, Home Life in Tokyo (1910), 17

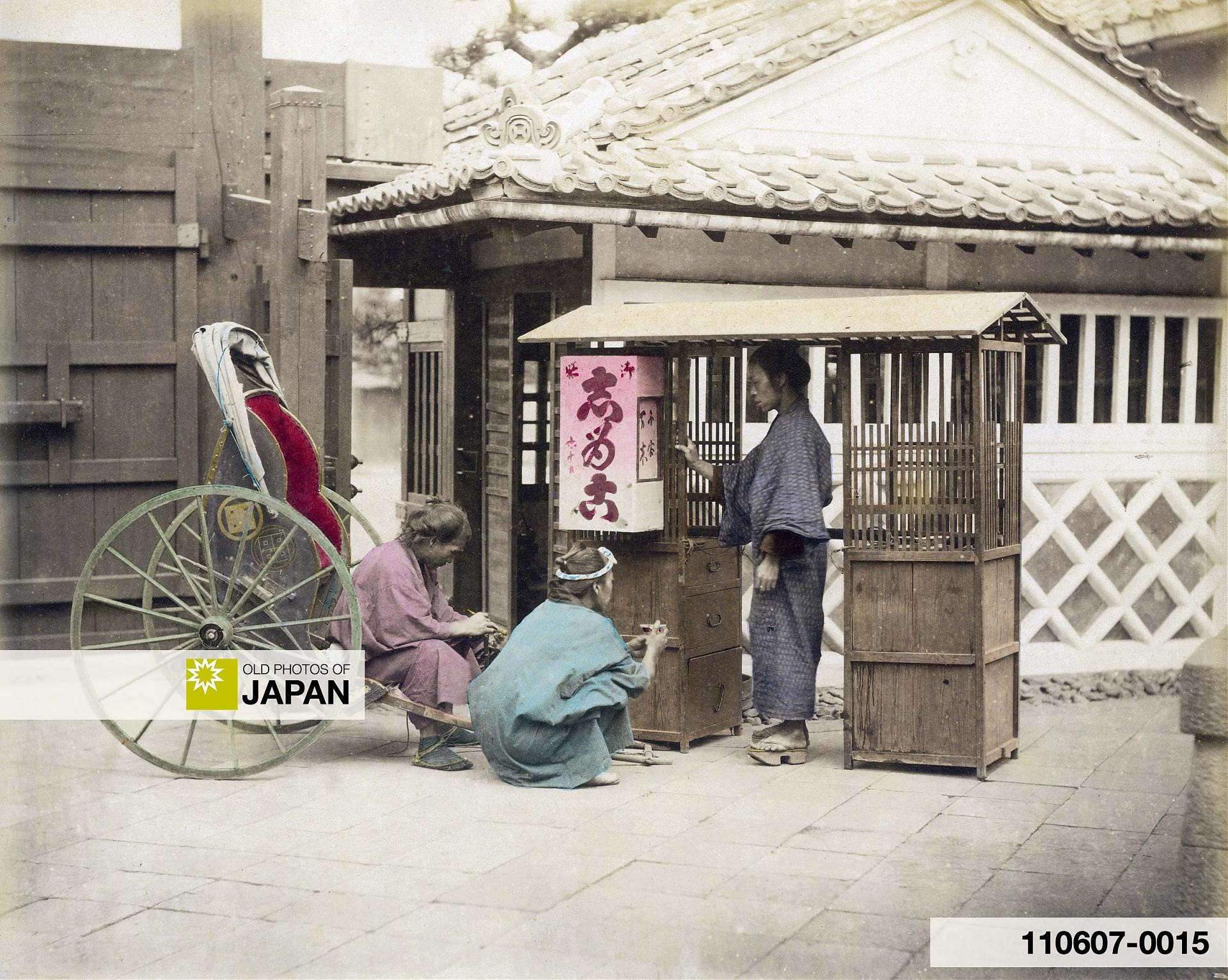

In this chaos, dedicated places where shafu could wait for customers sprung up, especially in front of hotels, stations and port entrances. In order to use such a place, shafu joined an organization known as a ban, essentially a sort of self-organized labor union. To join a ban, a shafu had to contribute a bottle of sake, an entrance fee and a monthly contribution.

Officially, the money was intended to assist ban members unable to work because of illness. But in practice, the funds were mostly used to buy food and drinks for the healthy members.

Most shafu were unaffiliated, they simply roamed the streets for customers and led an extremely hard and poor life. They generally rented their rickshaw for a sum known as chadai (茶代, tea money). The poorest even rented their jackets and breeches.19

It was a shafu’s dream to be in the regular employ of a well-to-do household. These jobs were paid better and came with fringe benefits. Sometimes even a small dwelling next to the rickshaw garage:20

He is well fed, as his is a severe physical work, and going as he does with his master to all sorts of places, he has to be treated well for fear he should give exaggerated accounts of petty family affairs at the houses where he waits for his master.

Jukichi Inouye, Home Life in Tokyo (1910), 162

This suggests that shafu were great sources of information. Scidmore wrote a beautiful description of a particularly well-informed runner by the name of Sanjiro:21

An army of jinrikisha coolies waits for passengers at the station, and among them is that Japanese Mercury, the winged-heeled Sanjiro, he of the shaven crown and gun-hammer topknot of samurai days. His biography includes a tour of Europe as the servant of a Japanese official. On returning to Tokio he took up the shafts of his kuruma again, and is the fountain-head of local news and gossip. He knows what stranger arrived yesterday, who gave dinner parties, in which tea-house the “man-of- war gentlemen” had a geisha dinner, where your friends paid visits, even what they bought, and for whom court or legation carriages were sent. He tells you whose house you are passing, what great man is in view, where the next matsuri will be, when the cherry blossoms will unfold, and what plays are coming out at the Shintomiza. Sanjiro is cyclopaedic at the theatre, and as a temple guide he exhales ecclesiastical lore. To take a passenger on a round of official calls, to and from state balls or a palace garden party, he finds bliss unalloyed, and his explanations pluck out the heart of the mystery of Tokio. “Mikado’s mamma,” prattles Sanjiro in his baby-English, as he trots past the green hedge and quiet gate of the Empress Dowager’s palace, and “Tenno San,” he murmurs, in awed tones, as the lancers and outriders of the Emperor appear.

Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, Jinrikisha Days in Japan (1900), 48

Winds of Change

Rickshaws had a great run for several decades, but by 1926 (Showa 1) they increasingly started to loose their popularity in urban areas. Soon they had mostly vanished from Japanese city streets. In rural areas they peaked around 1935 (Showa 10).

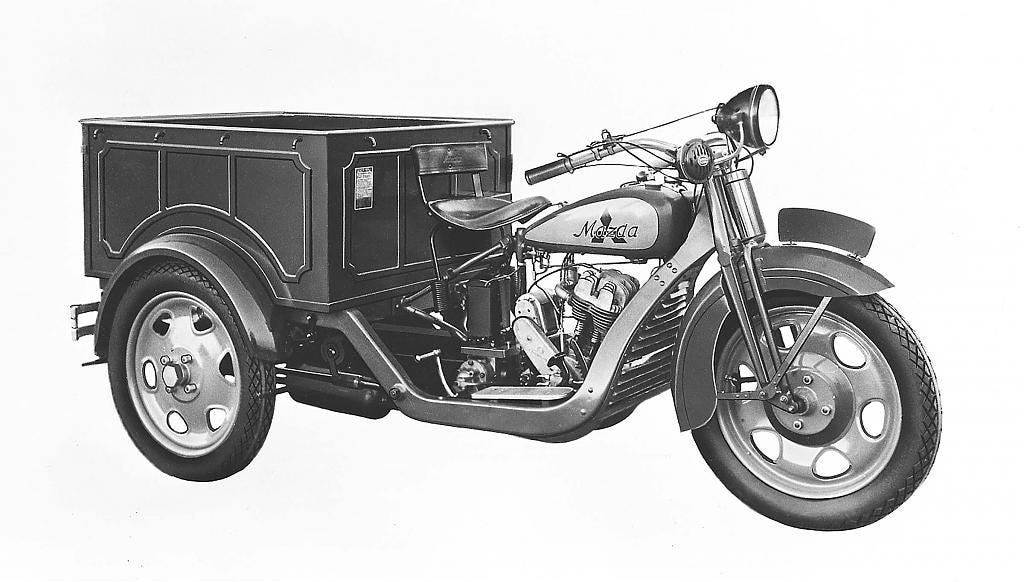

This coincided with Japan becoming the most industrialized country in east Asia. Developing inexpensive motorized vehicles had become a major goal of industrial policy. In 1931 (Showa 6), Hiroshima based Toyo Kogyo (東洋工業株) introduced the Mazda-Go (マツダ号). The 3-wheeled vehicle, also known as a tricycle truck or trike, resembled a motorcycle with an open wagon. It is now generally seen as the first auto rickshaw.

As no driver’s license was needed for trikes below 750cc, and taxes were lower for 3-wheeled vehicles, these auto rickshaws quickly became extremely popular in Japan. After the country introduced them overseas, they were soon found all over Southeast Asia as well.

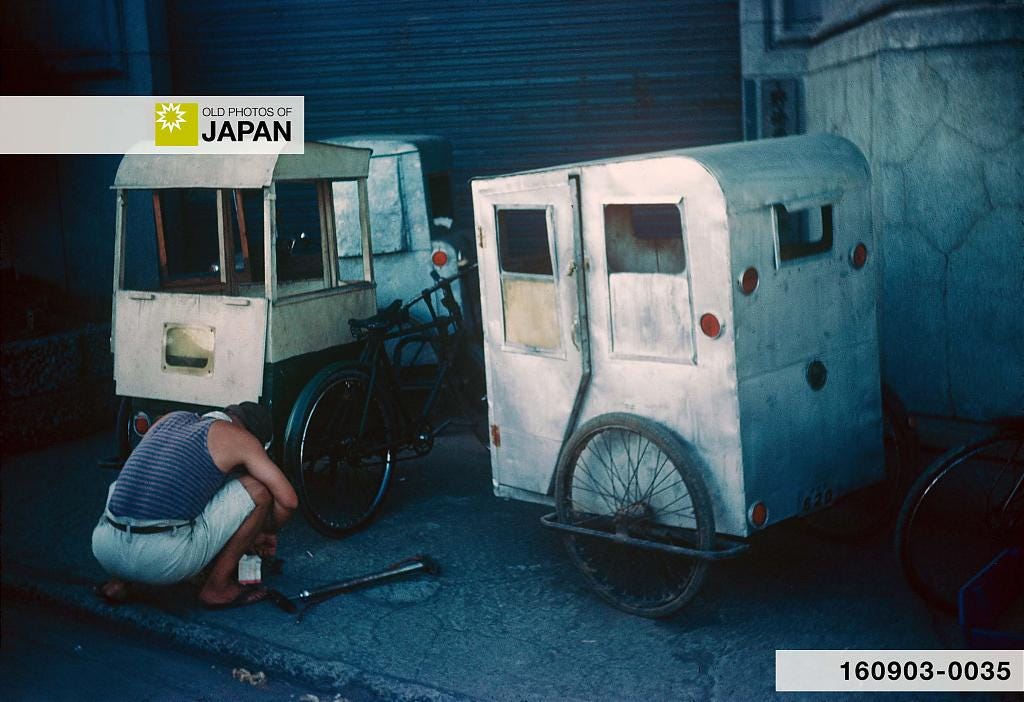

After the end of the Second World War, Japanese rickshaws got a second lease on life in the form of bicycle powered taxis known as rintaku (輪タク). Japan’s first postwar rintaku service was started around 1947 (Showa 22) in Tokyo. Although they were kind of a luxury service, within two years many variations had become a common sight nationwide.

Rintaku were not a new invention. The Saitama-based company Fukuda Shokai (福田商会) got a patent for their trailer-type rintaku called Fukuda style Fridcar (福田式フライドカー) in 1925 (Taisho 14).

However, as soon as Japan started to recover from the war, the rintaku lost their popularity. By the late 1950s, almost all had vanished from Japan’s streets. One vehicle that replaced them was the single-seater 3-wheeled mini-truck, a mid-sized auto rickshaw. Especially influential was the Daihatsu Midget, first manufactured in 1957 (Showa 32). A knock-down version of the Midget launched the auto rickshaw boom in Southeast Asia and Africa, that is still going strong today.

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 137.

Chamberlain, Basil Hall (1891). Things Japanese; being notes on various subjects connected with Japan for the use of travellers and others. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd., 242.

Harnessing man in an age of enlightenment. The East, Vol 32, No. 4, 1996 Nov/Dec. The East Publications, Inc.

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 140.

Browne, George Waldo (1901). The Far East and the new America; a picturesque and historic account of these lands and peoples. Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 323.

Scidmore, Eliza Ruhamah (1900). Jinrikisha Days in Japan. New York, London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 8.

Browne, George Waldo (1901). The Far East and the new America; a picturesque and historic account of these lands and peoples. Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 322–323.

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 140.

Von Baelz, Erwin O. E. (1974). Awakening Japan: the Diary of a German Doctor: Erwin Baelz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 77.

Harnessing man in an age of enlightenment. The East, Vol 32, No. 4, 1996 Nov/Dec. The East Publications, Inc.

ibid.

Bird, Isabella L. (1905). Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: An account of travels in the interior including visits to the aborigines of Yezo and the shrine of Nikko. London: John Murray: 5–6.

Harnessing man in an age of enlightenment. The East, Vol 32, No. 4, 1996 Nov/Dec. The East Publications, Inc.

ibid.

Chang, Ting (2016). Travel, Collecting, and Museums of Asian Art in Nineteenth-Century Paris. London, New York: Routledge, 84.

Harnessing man in an age of enlightenment. The East, Vol 32, No. 4, 1996 Nov/Dec. The East Publications, Inc.

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 138—139.

Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 17.

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 141–142.

Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 162.

Scidmore, Eliza Ruhamah (1900). Jinrikisha Days in Japan. New York, London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 48.