Shizuoka 1880s • Bridge on the Tōkaidō

Bridges on the Tōkaidō were far more common than is generally thought.

Hi, I am Kjeld Duits and I created Old Photos of Japan.

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for daily life in old Japan. I track down and acquire rare vintage prints and research and conserve them.

If you value or enjoy this work, please help support it!

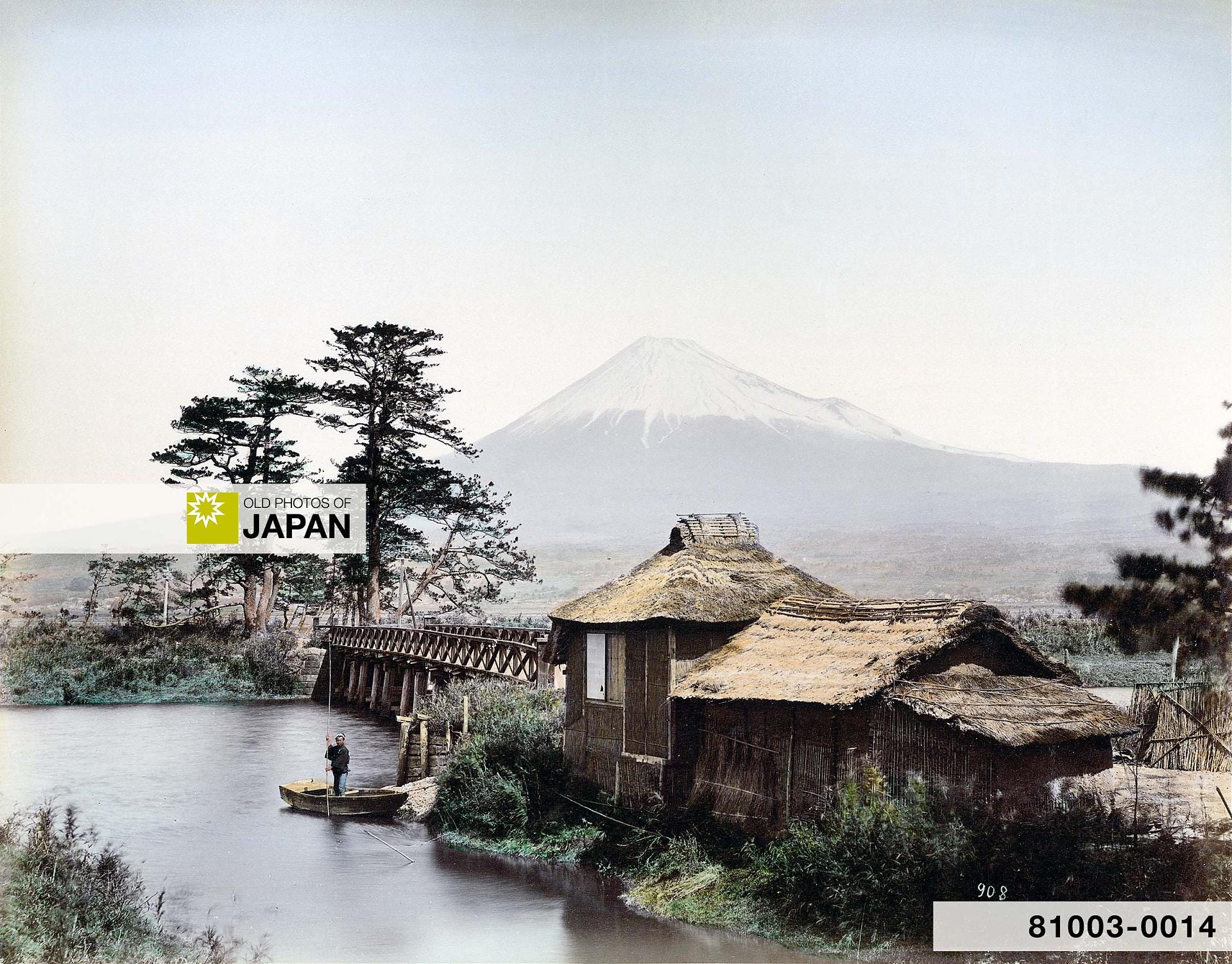

A bridge on the Tōkaidō with Mount Fuji in the back. Bridges on the Tōkaidō were far more common than is generally thought.

As we discovered in Crossing Japan’s Raging Rivers and Piggybacking the Tōkaidō’s Mightiest Rivers, many rivers in Japan could turn so wild that bridges could not be built. These rivers could only be crossed by ferry or with the help of specialized river porters.

Nonetheless, the Tōkaidō had a surprisingly large number of bridges.

Tokaido Water Crossings

This map shows major water crossings and ferry ports on the Tōkaidō and its extension, the Ōsaka Kaidō (between numbers 1 and 4). Each dot represents a station (宿, shuku). Blue stations have a major ferry or water crossing nearby.

The list below shows the names of the stations and rivers on the map as well as the type of water crossing. The numbers in the “Map” column refer to the numbers on the map. The “No.” column shows the Tōkaidō station numbers. For example, Otsu (number 4 on the map) is the 53rd station on the Tōkaidō.

These crossings are just the major ones. There were countless smaller ones on the Tōkaidō. Many of these featured a bridge.

We know exactly how many bridges thanks to ground-breaking research published in 2011 (Heisei 23) by transportation systems engineer Kenichi Takebe (武部健一, 1925–2015). Takebe counted an astounding 1,096 bridges:1

558 stone bridges

409 earthen bridges

129 wooden ones

“Earthen bridges” were wooden bridges with flattened earth on top, such as Kyoto’s famed Togetsukyō Bridge (not part of the Tōkaidō):

The great majority of the Tōkaidō bridges were small. Three quarters measured less than five and a half meters in length.

However, 23 bridges measured between 36 and 90 meters in length and six were over 90 meters. The longest bridge was at Okazaki (number 8 on the map) and measured over 283 meters. The second longest, at 227 meters, was at Kuwana (6).2

At 224 meters, the famous Seta no Karahashi Bridge (5) near Kyoto should be third. But it consisted of two bridges connected by an island and Takebe only included the larger one in his list. He measured it at almost 165 meters, making it the fourth-largest bridge on the Tōkaidō.

In comparison, the current Sanjō Ōhashi (3) in Kyoto is 73 meters long, while the Nihonbashi Bridge (4) in Tokyo measures about 50 meters.

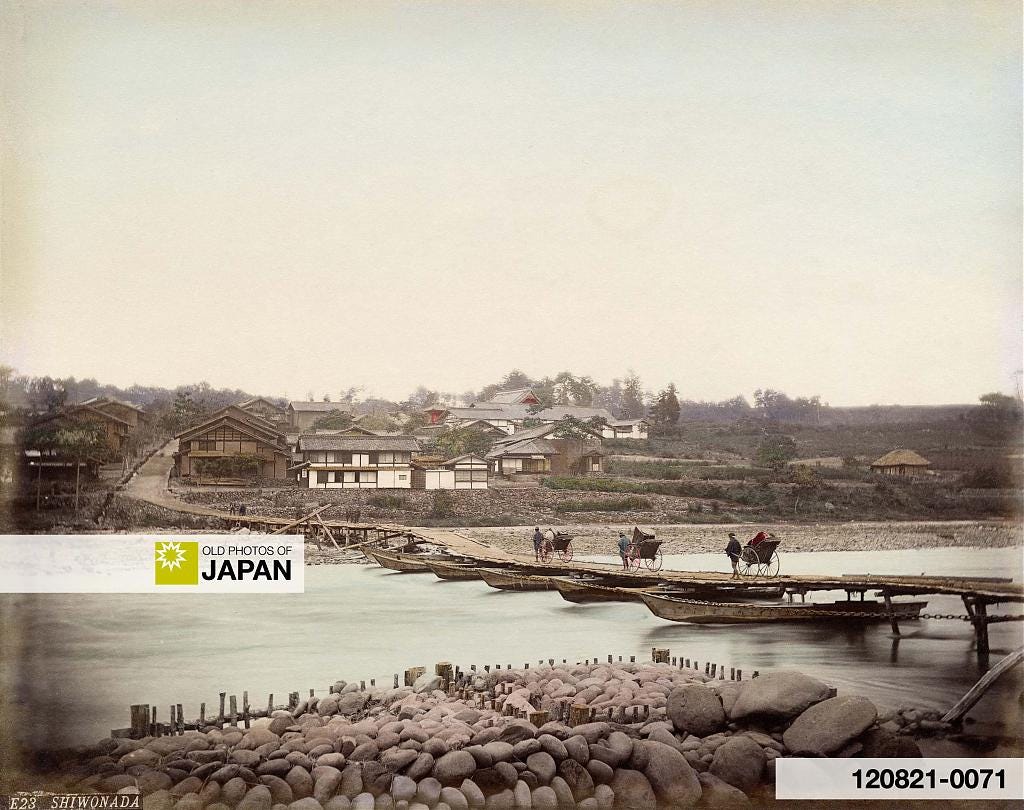

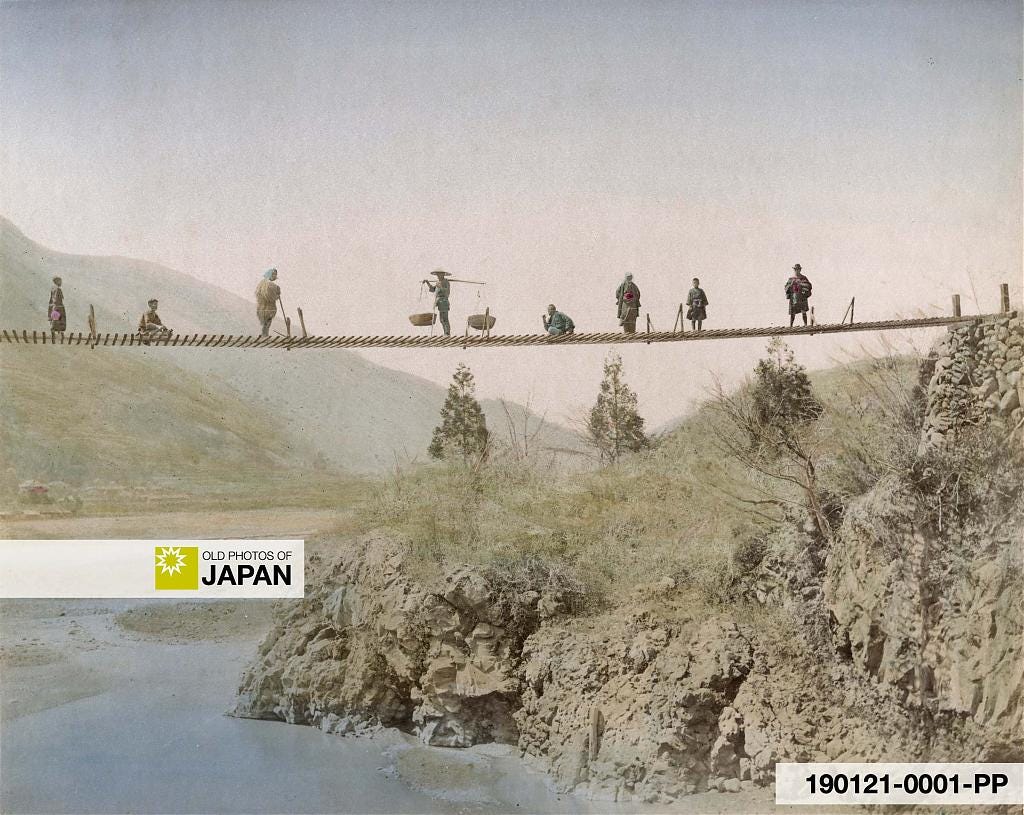

Some bridges were made with boats so they could more easily adjust to the changing water levels. During autumn and winter, when water levels were low, temporary bridges (仮橋, karibashi) were also built at many rivers.3 These could be pontoon bridges or simple wooden bridges.

Temporary Bridges

The use of temporary bridges, as well as the enormous variations in water levels described in Crossing Japan’s ‘Raging Rivers’, is beautifully illustrated by an anecdote culled from the Yokohama-based magazine The Far East. A december 1871 issue covered the first installment of a month-long journey into the countryside made by three Englishmen and their six Japanese attendants.

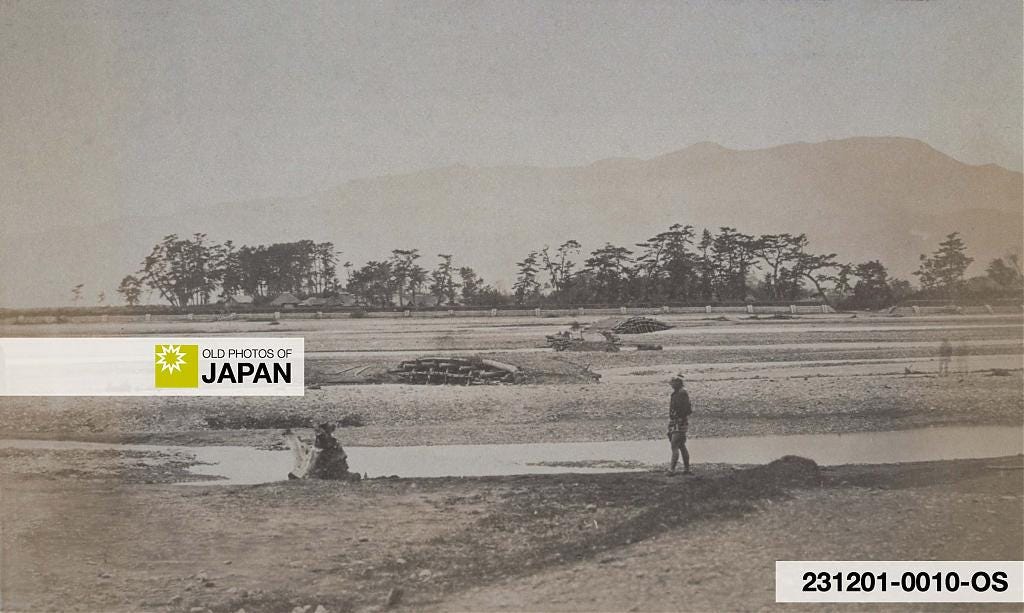

Near Odawara the party was carried across the intimidating waters of the Sakawagawa River (酒匂川, number 21 on the map). The water was as high as the chests of the porters, who struggled with the current. But when a photographer was later sent he only found “some four or five narrow streams” spanned by three small temporary bridges:4

When our photographer went to take pictures of the route described in the narrative, he found the mighty river reduced to a wide stony bed with some four or five narrow streams winding through it, and of these, three were bridged over.

The Far East (1871)

Temporary bridges may have been helpful, they also gave travelers a false sense of security that caused its own problems. The travel guide Ryokō Yōjinshū (旅行用心集, Precautions for Travelers), published in 1810 (Bunka 7) by author Yasumi Roan (八隅 蘆菴), specifically warned travelers about their dangers:5

No matter how small a river may be, you should not cross it carelessly when it is flooded, for its strong current will carry with it rocks and other things that may cause injuries.

Rivers in mountainous areas tend to dry up and their current may look rather weak, but once the winter snow melts or some summer showers fall, the water level may rise abruptly. The river will widen tremendously and it will be impossible to bridge it.

Temporary bridges put up to allow travelers to cross the shrunken rivers during the winter months are thus washed away every year. Some examples of these are the Sakawa River on the Tōkaidō, and the Shirakawa and Ōtawara rivers on the Ōshū Kaidō, but there are many others in the mountainous provinces.

When a river floods, neither wade through it or use a temporary bridge. Although not totally submerged in the water, such a structure may have had some of its pillars carried away by the current, and if you try to cross it, you may be swept away as well.

Ryokō Yōjinshū (1810)

Myth or Fact?

Countless accounts about the Tōkaidō claim that rivers on the route were not bridged because of military considerations. It would have slowed down western lords during an invasion of Edo, the seat of the Tokugawa government.

In his 1995 study Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan American historian Constantine Nomikos Vaporis convincingly argues against this notion. Many of such statements have no basis, he writes.6

Vaporis attributes the lack of bridges at certain rivers to topographical issues, technological limits, and socio-economic reasons.

For example, during the 1600s there was a bridge across the Tamagawa near Kawasaki, a strategic river crossing right on the doorstep of Edo. It was washed away in 1612, 1643, 1647, 1659, 1671, and 1680. Each time the shogunate rebuilt the bridge. But after it was washed away again in 1680 it gave up and a ferry system was used instead. From 1703, however, every year a small temporary bridge was built for use during fall and winter when water levels were low.7

At the center of the no bridges for defensive reasons argument has been the Ōigawa River, where travelers were carried across by specialized porters. It was 1.3 kilometers wide, significantly wider than the longest bridge on the Tōkaidō.8

Accounts about the Ōigawa often mention that a bridge was not allowed there because of military considerations. For most of the Edo Period (1603–1868) the motivations were actually economic, argues Vaporis:9

Whatever the reason for not bridging the Ōi early in the Tokugawa period, by the Genroku period [1688–1704], opposition to bridges was purely economic. For example, Kanaya and Shimada, the two post stations which operated the river crossing, fought petitions sent to local bakufu intendants by Edo merchants who wanted to operate a ferry crossing; they opposed these petitions on four separate occasions in thirteen years.

In one case, the petition got as far as the Magistrate of Finance before being refused. The statement presented to the Magistrate by the two post stations played upon the potent myth of strategic defense in order to protect their economic interests; it said, “If the prohibition which has been in effect up until now is lifted, then it will endanger the strategic natural defense of the realm (goyōgai wa yabure) and we will no longer be able to operate our river-fording services.”

Constantine Nomikos Vaporis, Breaking Barriers (1995)

This opposition was natural, writes Vaporis, because “a ferry-boat operation would have put many of the river-crossing porters out of work.” Their number was substantial—each station counted hundreds of porters. By the end of the Edo Period the two towns employed over 1300 porters.10

Vaporis adds that charges for ferries were “considerably lower than for fording.” Cutting out the porters would have ruined the economies of the two stations.

Takebe’s research, published 16 years after Breaking Barriers has strengthened Vaporis’ argument. It shows that there were in effect many bridges on the Tōkaidō, with 23 bridges measuring between 36 and 90 meters and six over 90 meters.

If the shogunate did indeed not want bridges on the Tōkaidō, then why were so many built—even one right on Edo’s doorstep?

DID YOU ENJOY THIS?

Help me research and save Japan’s visual heritage of everyday life.

SUPPORT OLD PHOTOS OF JAPAN | BUY AN ART PRINT

About the Photo

The top photo shows Kawaibashi Bridge (河合橋) spanning the Numakawa River (沼川) near Taganoura (田子の浦), in what is now Fuji, Shizuoka Prefecture. This spot was famous as one of the most scenic bridges on the Tōkaidō. There still is a bridge at this spot, but the beautiful view has long gone.

This photo is listed in the catalogue of Kimbei Kusakabe, but the site of the Nagasaki University Library claims it was taken by Shizuoka-based photographer Hanbei Mizuno (水野半兵衛).

Notes

武部健一(2011). 近世東海道の橋梁の全貌とその分析 土木学会土木史研究委員会 土木史研究 編 31 67-74, 2011.

ibid.

Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos (1995). Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan. Harvard East Asia Monographs, 54.

The Far East, Vol. II, No. XIII, December 1, 1871. Retrieved on 2024-02-01.

Vaporis, Constantine N. Caveat Viator. Advice to Travelers in the Edo Period. Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 44, no. 4, 1989, pp. 461–83. Retrieved on 2024-01-08.

Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos (1995). Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan. Harvard East Asia Monographs, 48–55.

ibid, 52–54.

武部健一(2011). 近世東海道の橋梁の全貌とその分析 土木学会土木史研究委員会 土木史研究 編 31 67-74, 2011.

Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos (1995). Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan. Harvard East Asia Monographs, 55.

Data provided by Shimada City.

Researching and writing this article I realized how much I have taken bridges for granted. In Japan we can now cross rivers just about everywhere, and they are rarely washed away. Even after powerful earthquakes most bridges somehow manage to survive these days.

It is a special occasion when a river becomes a true barrier obstructing our movements.

I only experienced how important bridges are when I covered the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami in Indonesia, and the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan.

In Pakistan my team got stuck at an isolated mountain village for many days after a heavy rainstorm washed away the nearby bridge which was weakened by the quake. Eventually, my guide and I decided to leave the car and driver behind, climbed down and up the steep river side, and walked out of the mountains.

The driver managed to get out about two weeks later after the Pakistani military built a temporary emergency bridge.

So beautiful. Amid all the dreary news, your article made me wander into bygone times (which were actually harsher...)