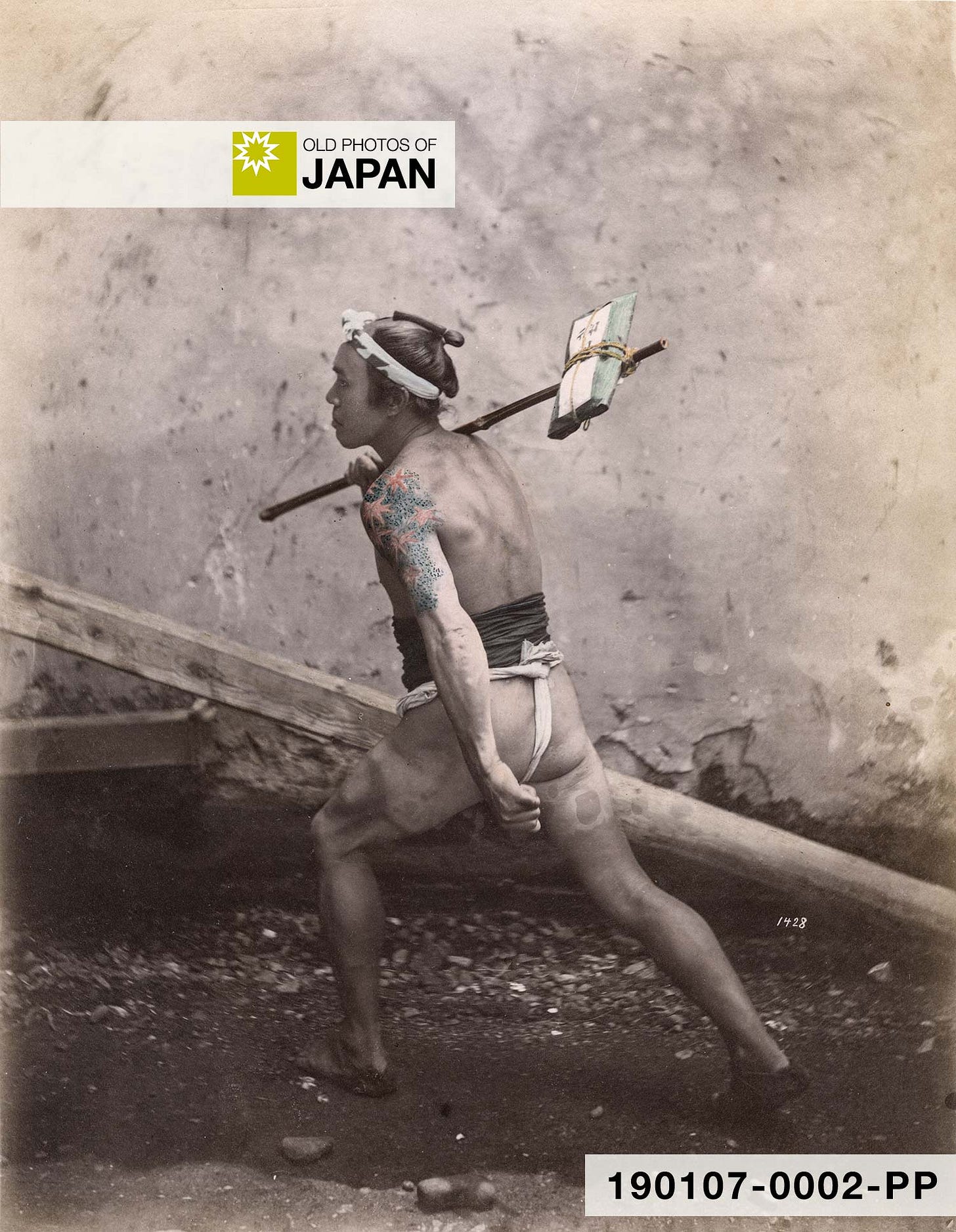

1890s • Running the Mail

This studio image of a Japanese express courier, or hikyaku (飛脚) is fake. When Kimbei Kusakabe (1841–1934) shot this scene in the 1890s, these near-naked runners had long since vanished.

Read this article on the site | Comment on this article.

When Japan opened up in the 1860s, the Western world had an unquenchable thirst for images of the country. Photographers like Felice Beato (1832–1909) responded by flooding the market with traditional scenes and subjects that were indelibly engraved onto the Western mind.

By the end of the 19th century, Japan had undergone radical social change and many of these scenes no longer existed. Hikyaku were gone, Japan now had a modern postal system. The mail was carried by horse-drawn carriages, steamships and trains. Mailmen, some of them mounted or on bicycles, wore dark uniforms with a fancy logo that looked like a T with a bar on top.

But the European and American visitors that purchased Kusakabe’s photographs at his Yokohama studio wanted souvenirs of the “real” Japan that they knew from the photographs of Beato and his pioneering colleagues.

To cater to this demand, Kusakabe recreated these scenes in his studio. As did other photographers. While there are countless photos of hikyaku, it is almost impossible to find vintage photographs of the modern mailmen of this period.

Though fake, courier runners as portrayed in the photographs of Kusakabe and his contemporaries are not make-believe. Hikyaku existed for several centuries and were absolutely crucial for domestic communications in old Japan.

There were three main systems, one run by the shogunate, one by the daimyo (feudal lords), and one by private companies, all with regularly spaced relay stations along Japan’s main highways:

• Tsugi-bikyaku (継飛脚)

By: High-ranking shogunate officials

Area: Along the Tokaido and Nakasendo highways

• Daimyo-bikyaku (大名飛脚)

By: Individual daimyo

Area: Between the daimyo's domains, rice warehouses and Edo (current Tokyo)

• Machi-bikyaku (町飛脚)

By: Merchants

Area: Edo, Kyoto and Osaka (areas of high economic activity)

In addition to these three, there were also specialized services. Such as kome-bikyaku (米飛脚), couriers that carried news about the latest rice prices from Osaka’s Dōjima Rice Exchange; and kane-bikyaku (金飛脚), who ran money orders.

Official messengers ran in pairs, one carrying the distinctive lacquered message box containing the letters, the other a pole with a lantern to light the way after sunset.

They had right of way—even over daimyo—and were allowed to cross rivers that had been flooded before anyone else who was waiting. They were even allowed passage at night at sekisho (関所) checking points, something that was strictly prohibited to most people.

Their freedom of movement is beautifully illustrated by an anecdote from one of Japan’s best known historical events, dramatized in countless movies and TV series. In 1864, the Shinsengumi, the Bakufu’s special police force in Kyoto, attacked anti-shogunate samurai during the infamous Ikedaya Incident. One of them, Kumajiro Ariyoshi (有吉熊次郎, 1842–1864), was able to escape Kyoto by disguising himself as a hikyaku.

Machi-bikyaku, an independent network of couriers first organized around 1664, were most common. Like other hikyaku, they wore little more than a fundoshi loin cloth and straw sandals, regardless of the weather. This apparently gave them greater running comfort, especially in months of severe humidity.1

Morisada Mankō (守貞謾稿, Morisada’s Sketches), an Edo-period encyclopedia of everyday life, describes how machi-bikyaku were nicknamed jingle jingle town couriers (ちりんちりんの町飛脚, chirin chirin no machi-bikyaku) because of the bells dangling from the front end of the bamboo pole holding the lacquered box.2 The bells warned people that a courier was about to pass and that they should make way. The approaching bells also informed runners at a relay station to get ready to take over.

German author and diplomat Rudolf Lindau (1829-1910), who lived in Japan in the early 1860s, was astonished by the couriers’ speed. In just twenty-four hours, he wrote, they could cover a distance of more than 200 kilometers (124 miles). “They go with bent knees, skim the ground with their feet, and breathe loudly.”3

Celebrated German physician and botanist Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866) who lived at the Dutch trading station at Nagasaki’s Dejima during the 1820s, decades before Japan opened its borders, also wrote about hikyaku:4

A post for letters is established throughout the empire, which, though pedestrian, is said to be wonderfully expeditious. Every carrier is accompanied by a partner, to guard against the possibility of delay from any accident that may chance to befall him. The men run at their utmost speed, and upon nearing the end of their stage, find the relay carriers awaiting them, to whom the packet is tossed the moment they are within reach of each other. The relay postmen have already started before the arriving postmen have stopped. The greatest prince of the empire, if he meets the postmen on the road, must give way, with his whole train, and take care that their course be not obstructed by him or his.

Manners and Customs of the Japanese, in the Nineteenth Century (1841), 326–327

Another Western visitor impressed by the courier system was British diplomat Rutherford Alcock (1809–1897), who was stationed in Japan between 1858 (Ansei 5) and 1864 (Bunkyū 4). In The Capital of the Tycoon, he recalled an encounter with government couriers:5

I saw two men stripped to their loin-cloths approaching at a quick trot, one of them carrying over his shoulder a carefully-secured packet, and every one instantly getting out of their way. I immediately recognized by these signs an express with Government dispatches, and for a moment hoped they might be mine; but, without deigning to look at us, they sped swiftly on.

The Capital of the Tycoon Vol. II (1863), 135

Most companies used the so-called sando hikyaku (三度飛脚) system, sending and receiving mail every ten days. By the end of the 17th century, a message generally took about six days to cover the 500 kilometers (roughly 300 miles) between Kyoto and Edo. But as business boomed and traffic increased, this slowed down to ten or twelve days.

As a result, a super express courier service (早飛脚, hayabikyaku) was launched. These runners even ran at night and could make the trip in three and a half to five days. Companies charged high rates for this extra fast service. The cheapest service on the other hand took about a month, and offered no guarantee for time of arrival.

Interestingly, letters were not delivered to the people they were addressed to. Hikyaku placed them on a mat in front of the way station, where the addressee had to apply for them. Responses were handed over on the hikyaku’s return trip. There were no stamps. Coins were pasted to the letter.6

… it was customary to prepare letters when the courier had called and hand them over to him on his return. In Edo an open straw bag was fixed to the edge of the Nihonbashi Bridge in the morning announcing the arrival of an express messenger from Osaka. Those who wanted to send a letter to Osaka, would put it into the bag with the fixed fee attached to it. In the evening, the messenger would take the bag swollen with mail and immediately start on his return journey to Osaka.

The System of Communications at the Time of the Meiji Restoration (1941)

Hikyaku must have had tons of stories to tell. On highways like the Tokaido and the Nakasendo, they ran through towns, villages and the countryside, and crossed raging rivers, high mountain passes, and thick forests.

They would see the famous Nihonbashi Bridge from which all roads were measured, sacred Mount Fuji, and the monumental temples of Kyoto. They would see rice sprouting in spring, and farmers hauling in the harvests during autumn.

They would defy rain and snow, cold and heat, exhaustion and thirst, and had to ward off wild animals, thiefs and robbers. Physically, it must have been an extremely demanding job. But the hikyaku must also have felt a strong sense of freedom, accomplishment and excitement.

It couldn’t however last forever. Soon after Japan’s modern postal service was inaugurated in 1871 (Meiji 4), the near-naked hikyaku vanished from Japan’s roads. They were replaced by postal employees in black uniforms.

The World of Hikyaku

Some scenes that hikyaku would have regularly seen in the 19th century:

Afterthought

There is something fascinating in many old photographs of hikyaku. When you look carefully, you will notice that quite a few move the left shoulder and arm together with the left leg (or the right arm with the right leg). This is known as an ipsilateral gait. It is even seen in illustrations. Modern professional runners on the other hand use the opposing arm, known as a contralateral gait.

Using an ipsilateral gait seems counter-intuitive. Did the hikyaku really run that way, or was this pose merely used for dramatic effect in the photograph?

Connect

Share your insights, comments and questions.

Shores , Matthew W. (2010) Long Before Asics and Mizuno: Hikyaku, Japan’s First Running Elite.

Kitagawa Morisada (喜田川守貞・本名:北川庄兵衛). Morisada Mankō Vol. 5 (守貞謾稿 巻5). 000007325546, National Diet Library.

Lindau, Rudolf (1864). Un voyage autour du Japon. Hachette et cie, 208–209.

Von Siebold, Philipp Franz (1841). Manners and Customs of the Japanese, in the Nineteenth Century: From the Accounts of Recent Dutch Residents of Japan, and from the German Work of Dr. Ph. Fr. Von Siebold. London: John Murray, 326–327.

Alcock, Rutherford (1863). The Capital of The Tycoon: A Narrative of a Three Years’ Residence in Japan VOL. II. New York: The Bradley Company, Publishers, 135.

Mitsui, Baron Takaharu. The System of Communications at the Time of the Meiji Restoration. Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Jan., 1941), 88-101.