Piggybacking the Tōkaidō's Mightiest Rivers

How did travelers in old Japan cross rivers without bridges and ferries?

Hi, I am Kjeld Duits and I created Old Photos of Japan.

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for daily life in old Japan. I track down and acquire rare vintage prints and research and conserve them.

If you value or enjoy this work, please help support it!

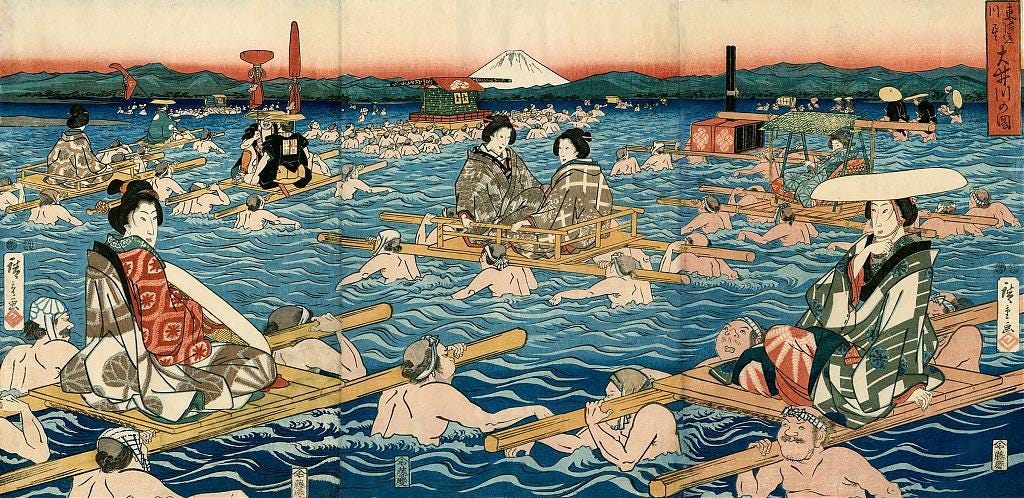

Japanese porters carrying travelers across a wide river. For centuries this was the only way to cross several rivers on the storied Tōkaidō highway.

One of the best eyewitness accounts we have of travel in Japan during the Edo Period (1603–1868) was written by German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716), who lived in Japan from 1690 through 1692. In his account of his journey to Edo he explained how some rivers could only be forded:1

We have to cross a number of rivers—especially traveling the Tōkaidō—that, on account of the nearby snow-covered, high mountains, run to the sea with such force, particularly after a heavy rainfall, that they overflow their bed of stony shoals and can be crossed neither by bridges nor by boats. So travelers have to wade through these rivers, and horses and riders are entrusted to certain local people to guide them across the water. Specifically engaged for the crossing, these people are familiar with the topography and know how to support the horse carefully with their arms against the force of the river and the rolling stones. Norimono [Japanese palanquins] are lifted up with the hands and are carried across only by these people.

Engelbert Kaempfer

One such river was the Ōigawa River in what is today Shizuoka Prefecture. It was arguably the most feared river in Japan. Kaempfer, who crossed this river four times, introduced it as follows:2

Its waters gush with the speed and power of an arrow, and it cannot be crossed on horseback without knowledgable, specially appointed guides (of which five have to guide one horse when the water is low, that is, knee-deep). If they loose their passenger, they lose their lives.

Engelbert Kaempfer

The fear that the Ōigawa stirred in travelers’ hearts was captured in Hizakurige (1802–1822), a popular comic novel written as a traveler’s guide for the Tōkaidō, known in English as Shank’s Mare. When the story’s two protagonists cross the Ōigawa “the rolling waters of the river” make them fear for their lives:3

Soon their eyes were dizzy by the sight of the rolling waters of the river. So frightened were they that they thought at every moment they would lose their lives. There is, indeed, no more dreadful place on the Tokaidō than the River Ōi, the swift current of which sends great rocks rolling down and threatening to smash you every moment.

Jippensha Ikku, Hizakurige (1802–1822)

Not only the Ōigawa evoked fear. The travel guide Ryokō Yōjinshū (旅行用心集, Precautions for Travelers), published in 1810 (Bunka 7) by author Yasumi Roan (八隅 蘆菴), warned that river crossings could upset unprepared women and children:4

You should take certain precautions at river-crossings when you are traveling with women and children. Unlike men, women are timid creatures and sometimes are frightened when they look at the fast current of a wide river. Also at times they are afraid of the disorderly conduct of the river porters and may get light-headed or dizzy. For this reason you should carefully explain to them the day before that the crossing site will be bustling with activity and that even if they become temporarily separated from their travel companions, there is no reason to become frightened. Post-station officials are on duty at such places and thus there is no cause for any concern of the part of the traveler.

Ryokō Yōjinshū (1810)

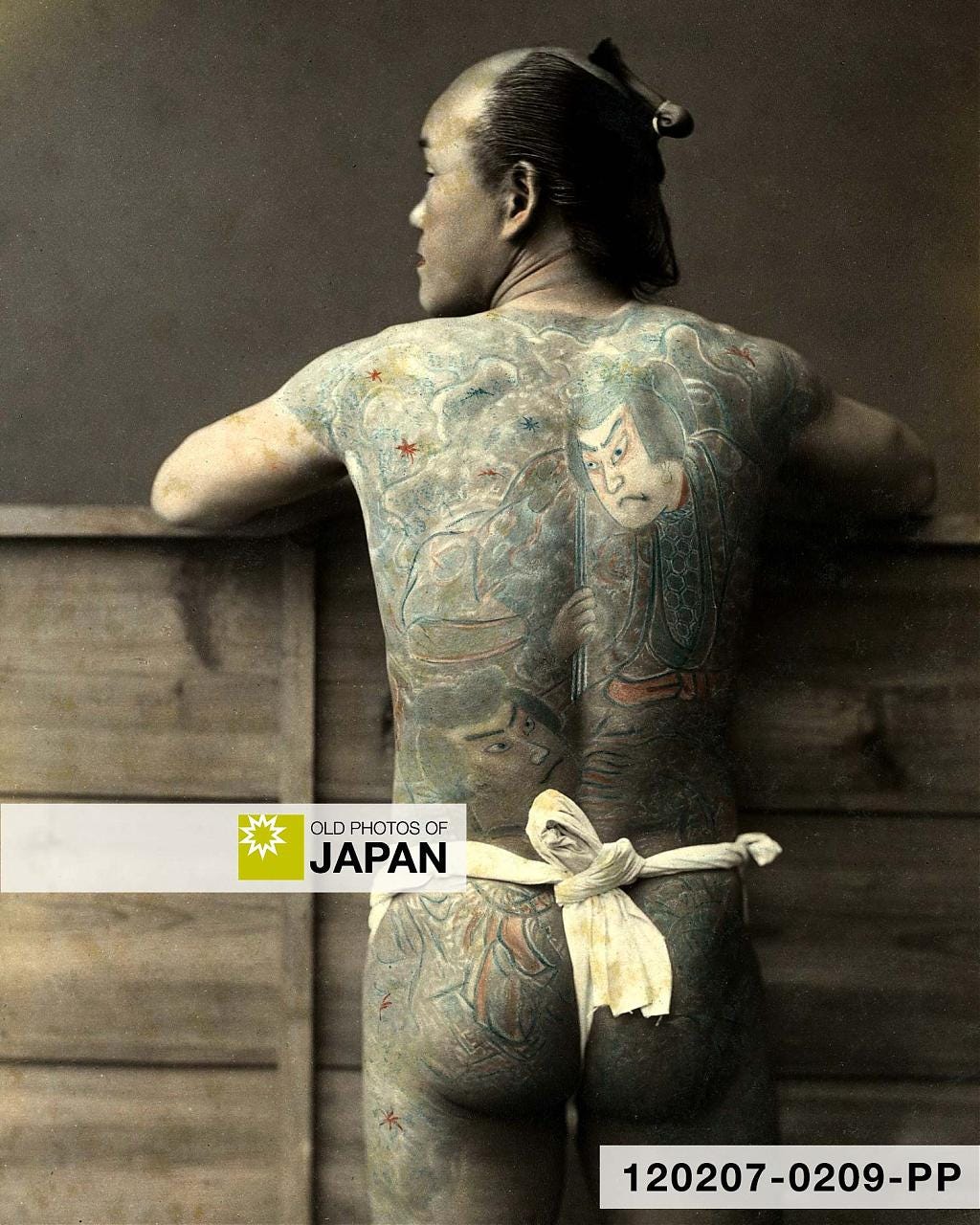

Roan’s account of “disorderly conduct” by porters differs significantly from the observations of Swiss diplomat Aimé Humbert (1819–1900), who visited Japan in 1863–1864 (Bunkyū 3–Genji 1). His brief account of such crossings specifically described the porters as extremely orderly, albeit quite colorful:5

Rivers over which native builders have been unable, despite all their skill, to establish bridges, must be crossed on flat boats or on the shoulders of sturdy porters, specially assigned to ford the river. It’s a profession they hand from father to son. They even form a guild, which indemnifies travelers in the event of personal accident or damage to luggage. A handkerchief tied over the forehead and a loincloth around the hips make up their entire costume. For the rest of the body, tattoos take the place of clothing, as is the general practice among the coolies of major Japanese cities.

Aimé Humbert, Le Tour du Monde (1867)

Humbert continued with more details:6

Passenger fares, which are always extremely moderate, vary according to whether you hire eight men to carry you in a norimon, or four men with a litter, or two men and a stretcher, or just a porter. In the latter case, which is the most frequent, the traveler straddles the porter’s neck, and the porter, grabbing the traveler by both legs and advising him to keep his balance, advances into the water with slow, firm and measured steps. The process is the same for natives of both sexes. They take to it with equal docility, and walk in unison, smoking their pipes and sharing their observations on the height of the water and the length of the journey.

Aimé Humbert, Le Tour du Monde (1867)

In 1871 (Meiji 4), only seven years after Humbert’s observations, the Ōigawa porters were replaced by ferries. In 1879 (Meiji 12) the first bridge was built.7

Services

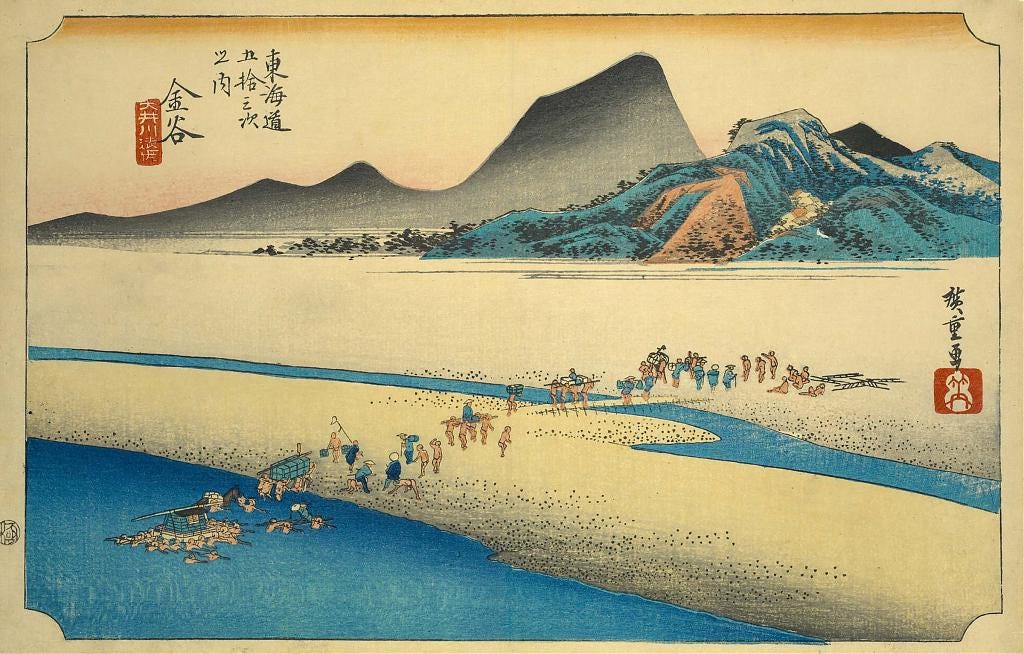

The Ōigawa featured in many ukiyoe of the Tōkaidō. An Utagawa Hiroshige print of the river beautifully documents the different crossing services that the specialized river porters (川越人足, kawagoshi ninsoku) offered.

There were basically two different ways of crossing the Ōigawa, on a porter’s shoulders (seen in number 4 in the detail image) or on a platform known as a rendai (輦台, seen in numbers 1, 5 and 6). The rendai were subdivided into three classes:

The daikoran-rendai (大高欄輦台, number 1) was used mainly for daimyo (feudal lords). It was the largest, and most expensive and came with high handrails around the edges and generally required 16 to 24 porters. If the palanquin placed on it was large it could have as many as 30, including a guide leading the way.

Next came the hankōran rendai (半高欄連台), seen in the engraving at the top of the page. This was for important people, came with low handrails, and required four porters for a single passenger.

Hira rendai (平輦台, 5 and 6) were for commoners. They looked like ladders, had no handrails, and required four porters for one passenger, or six for two.

Like their services, the porters themselves were also divided into ranks depending on their experience. Porters started around the age of 12 and underwent many years of rigorous training in the difficult wading skills before they were allowed to carry travelers.

River crossing was big business for Shimada and Kanaya, the two stations on each side of the Ōigawa. By the end of the Edo Period (1603–1868) the two towns counted over 1300 porters.8

DID YOU ENJOY THIS?

Help me research and save Japan’s visual heritage of everyday life.

SUPPORT OLD PHOTOS OF JAPAN | BUY AN ART PRINT

Glossary

Recommended Primary Sources

Shukuson Taigaichō (宿村大概帳)

A collection of 53 volumes of records of Japan’s five main highways and their byways surveyed by the Shogunate during the 1840s~50s. It contains detailed descriptions of the status of each station and village along each road, including population, number of houses, main lodges, number of inns, size of roads, bridges, temples and shrines, local industries, special products, and more.

Tōkaidō Bunken Ezu (東海道分間絵図)

An important dōchūzu (道中図, road map) depicting the Tōkaidō and everyday scenes along the route. It shows details like distance markers, guideposts, checkpoints, inns, rivers, bridges, and more. The map reproduces the 486 kilometers of the road in about 36 meters. The map was first drawn in 1690 (Genroku 3) and probably intended for virtual travel.

Notes

Kaempfer, Engelbert; Bodart-Bailey, Beatrice M. (1999) Kaempfer’s Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 249–250.

ibid, 56.

Jippensha, Ikku; Satchell, Thomas (1960). Shanks’ Mare. Being a translation of the Tokaido volumes of Hizakurige, Japan’s great comic novel of travel & ribaldry by Ikku Jippensha (1765–1831). Vermont, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 100–101.

Vaporis, Constantine N. Caveat Viator. Advice to Travelers in the Edo Period. Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 44, no. 4, 1989, pp. 461–83. Retrieved on 2024-01-08.

Humbert, Aimé (1867). Le Tour du Monde: Nouveau Journal des Voyages. 1867, Premier Semestre. Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie., 292.

ibid.

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 136.

Some sources claim that the service was discontinued in 1870 (Meiji 3).

Data provided by Shimada City.