Spotlight • Empire of Color (1)

How 19th century Japanese artists mastered the art of hand colored photography — How photography reached Japan.

Read on the site | Comment | Support

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4

Some people think that I colored the vintage photos in my collection. They were actually tinted by the studios that published them in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Experienced artisans added the color to monochrome albumen prints. Their work was often meticulous and masterful. Using transparent water colors to keep the important details of each photo visible, they applied slightly different hues to create intricate shading. When there were rocks in a garden, or baskets on a cart, the artists tried to give each its own individual tone and texture.

Often, artists did not cover the whole photo with paint. Many tried to only add color where it made a significant difference, a practice first explored by ukiyoe woodblock printers.

When done well—which was not always the case—the result touches the observer more profoundly than modern color photography which feels flat in comparison. In the top photo of a village street it feels like you can touch the dirt on the children’s clothing, while the brightly colored foreground attracts the eyes to the action, mimicking the way we naturally look at the world. The print has an almost three-dimensional depth, accomplished largely by the judiciously applied color.

By the late 1800s Japan had become world famous for the magical quality of its hand colored photographs, a stunning synthesis of modern Western technology and traditional Japanese artisanship. This artistry did not just happen. It took Japanese photographers several decades to master the required skills.

This essay introduces the fascinating and barely known history of Japanese hand coloring, starting from the introduction of photography and ending with its legacy.

The essay has been separated into four parts. Part 1 looks at how photography reached Japan. The other three articles will be published over the following days.

A New Invention

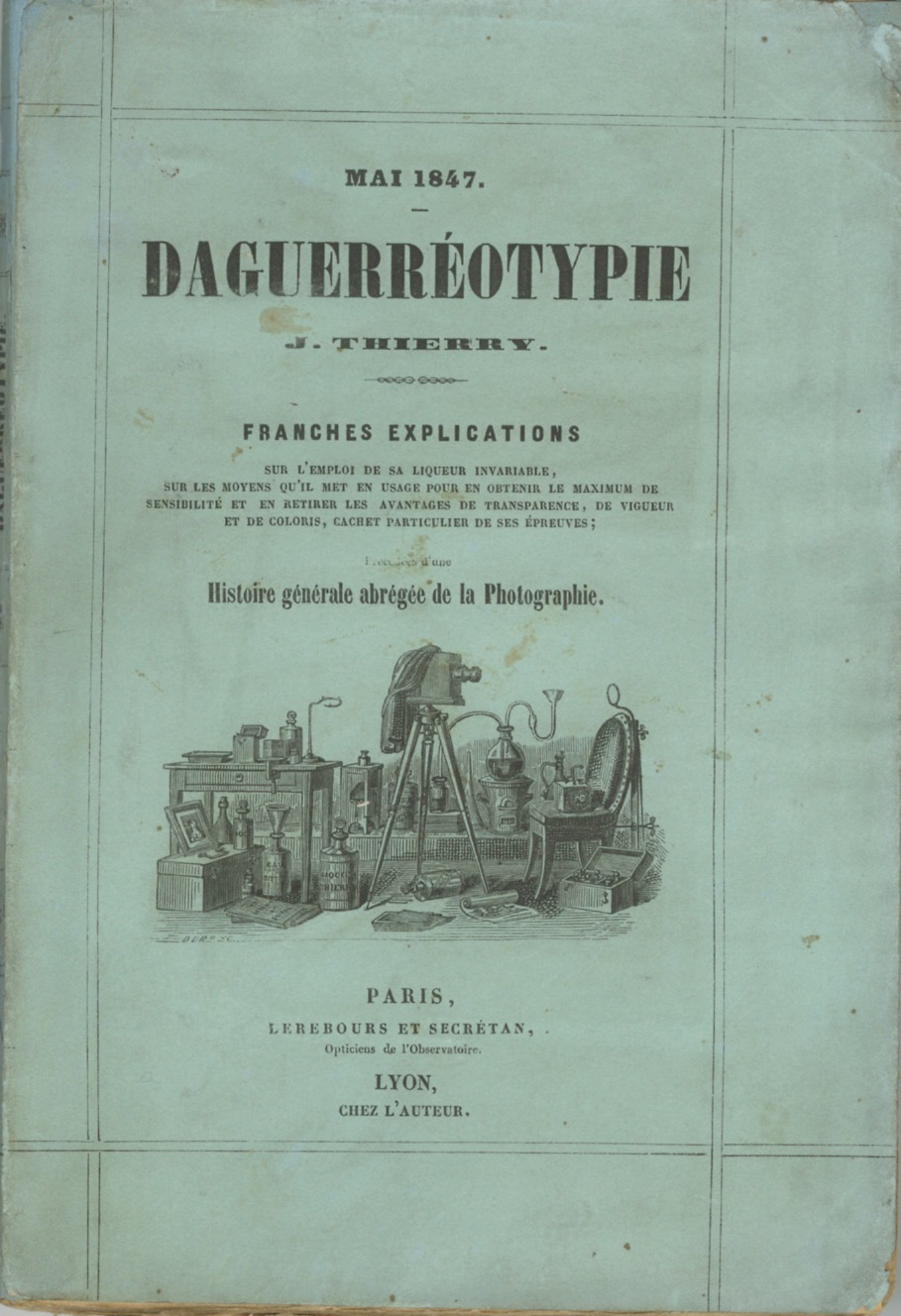

Practical photography started when French artist Louis Daguerre (1787– 1851) announced his invention of the daguerreotype in 1839 (Tenpō 10). Shortly after, the French government purchased the rights and offered the process as a free gift to the world. It also published Daguerre’s complete working instructions in eight languages.

The utilitarian outlook on life that accompanied the Industrial Revolution raised the expectations of photography into the clouds. Upon introducing the bill to purchase the rights of Daguerre’s photographic process, France’s Minister of the Interior, Tanneguay Duchâtel (1803–1867), asserted that the invention’s “immense utility” were “beyond calculation”.1

It will easily be conceived what resources, what new facility it will afford to the study of science, and, as regards the fine arts, the services it is capable of rendering, are beyond calculation.

Tanneguay Duchâtel, 1839

These high expectations and the promotion by the French government helped photography spread like wildfire. The pyramids in Egypt were photographed only a few months after the daguerreotype process was published.2

Photography thrilled people. In 1843 (Tenpō 14), British poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861) wrote a letter about the new invention to author and dramatist Mary Russell Mitford (1787–1855). Browning’s excitement is palpable:3

My dearest Miss Mitford, do you know anything about that wonderful invention of the day, called the Daguerrotype? [sic] — that is, have you seen any portraits produced by means of it? Think of a man sitting down in the sun and leaving his facsimile in all its full completion of outline and shadow, stedfast on a plate, at the end of a minute and a half! — The Mesmeric disembodiment of spirits strikes one as a degree less marvellous. And several of these wonderful portraits . . like engravings only exquisite and delicate beyond the work of graver — have I seen lately — longing to have such a memorial of every Being dear to me in the world.

It is not merely the likeness which is precious in such cases — but the association, and the sense of nearness involved in the thing . . the fact of the very shadow of the person lying there fixed for ever! It is the very sanctification of portraits I think — and it is not at all monstrous in me to say what my brothers cry out against so vehemently . . that I would rather have such a memorial of one I dearly loved, than the noblest Artist’s work every produced. I do not say so in respect (of disrespect) to Art, but for Love’s sake. Will you understand? — even if you will not agree? —

Ever your affectionate B B

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, December 7, 1843

In spite of all the enthusiasm the new invention inspired, it took a long time before photography was mastered by the Japanese. Since the early 1600s the Tokugawa Shogunate had limited all contact with the outside world—no travel abroad, limited trade, and closed borders for most foreigners. This greatly hindered the acquisition of the required equipment, chemicals, and technical skills.

The invention in 1851 (Kaei 4) of albumen paper prints from wet collodion glass negatives made photography significantly simpler. Exposure time was shorter, multiple prints could be made from a single plate, and it was inexpensive. But the hurdles remained high as British author Terry Bennett explains in his 2006 landmark study Photography in Japan 1853–1912:4

The typical camera at that time was a heavy wooden box fitted with a fragile glass lens. A pristine glass plate would need to be evenly coated with a wet-collodion solution and then sensitized in a darkroom with silver nitrate. The glass plate was then carefully inserted into the camera and the lens cap was taken away to expose the plate to the view the lens had been pointing at. Estimating the appropriate exposure time, which could be anything from a few seconds to a few minutes, was largely a matter of lighting conditions, intuition, experience, and luck. The lens cap would then be replaced and the glass plate removed and taken back to the darkroom for further chemical treatment. The aim here was to “fix” the image on the plate, which then became the glass negative. If the process had been successful, then prints could be taken from the negative. But even this printing required a significant degree of skill and dexterity.

Imagine, also, the various accessories which would be an essential part of any photographer’s baggage, Apart from the camera and darkroom (a portable tent if traveling), he would need a tripod, various lenses, a large number of fragile glass plates, bottles of chemicals, and fresh water. These hard-to-get and relatively expensive chemicals would need to be mixed in the right proportions.

Terry Bennett, Photography in Japan 1853–1912 (2006), 24

The First Cameras in Japan

The first cameras entered Japan through the Dutch trading post on Nagasaki’s Dejima island. By 1855 (Ansei 2) at least five cameras had reached Japan through this route.5

These cameras are believed to have ended up with daimyō. In 1849 (Kaei 2), one of them was sold to Shimazu Nariakira (島津 斉彬, 1809—1858), the future daimyō of the Satsuma domain who was fascinated by Western science and technology.

The retainers he appointed to experiment with the camera found it exceedingly difficult. It took until late 1857 (Ansei 4) before they finally managed to create a discernible image—eight years after the purchase and 18 years after Daguerre’s announcement.

This photograph, a portrait of Shimazu in formal attire, is now held at Kagoshima’s Shoko Shuseikan Museum. It is considered to be the oldest daguerreotype taken in Japan by a Japanese. In 1999 it was designated an Important Cultural Property.6

Learning the Craft

Although there were at least five cameras in Japan by 1855, the struggle to capture an image with Shimazu’s camera reveals that a crucial ingredient was missing: knowledge on how to use them. Three people helped remedy this, two Dutch doctors posted to Dejima, and a Swiss photographer traveling around Asia.

On August 2, 1853 (Kaei 6) Dutch doctor Jan Karel van den Broek (1814–1865) landed at Dejima. He had been employed by the government of the Dutch East Indies to function as the physician of the Dutch trading post.

Van den Broek arrived at a unique time—many Japanese intellectuals felt the country had to catch up with the Western powers which were seen as a threat to Japan’s sovereignty. There was an insatiable hunger for knowledge of advanced Western science. Overnight, Van den Broek became the go-to person to answer questions on subjects ranging from chemistry to gunnery:7

I like the Japanese very much: they are an intelligent and cheerful people; they want to know a lot and besiege my house all morning; sometimes I receive more than 20 Japanese visitors and usually a few doctors. You cannot imagine the peculiar questions they ask me; sometimes I have to act as a chemist, then as a physicist, next as an artillerist.

Dr. Jan Karel van den Broek, 1853

Van den Broek was the perfect person to respond to these questions. He was a talented scientist and had a vision. While his predecessors at Dejima—like Kaempfer (1651–1716) and Von Siebold (1796–1866)—saw it as their main task to bring Japan to the world, Van den Broek wanted to bring the world to Japan.

His office featured an electrical generator, an electric battery, a working telegraph, a microscope, a telescope, and even a wooden model of a steam engine. What he had been unable to bring with him, he created. When asked by his Japanese visitors about the workings of an iron foundry, Van den Broek had a wooden model made of a reverberatory furnace.8

Van den Broek’s influence on Japan’s modernization was significant—in 1856 (Ansei 3) he received an astonishing 5,000 Japanese visitors.9 His advice led to the construction of several factories and foundries, and the first steam engine constructed by Japanese was based on his instructions.10

In 1854 (Kaei 7), Van den Broek sent the Dutch government a secret letter requesting more than 60 Western instruments, models and tools. The second item on this list was a Daguerreotype-camera and accessories. He had also brought his own camera.

A letter from July 1856 states that he was successfully using one or both of these cameras, and was about to start teaching photography to Japanese students.11

At the occasion of a visit to my home by His Excellency the Governor of Nagasaki, the Ometsuke and his Excellency the Minister of the Navy of Japan, Mr Nagai, we talked of photography and I was asked if I had photographed myself. I showed some samples of photography made by myself and a few very beautiful photographs of Constantinopel, given to me by the count of Limburg Stirum. I remarked that I could not continue before I had silver and that this had to come from Holland as the comprador were not allowed to deliver silver. The Governor said that he would have silver delivered to me.

Recently the Chief Interpreter Tobei, the interpreter Sjoso and Doctor Ke[i]sai have been here to ask in the name of the Governor to teach Mr Keisai the photographic science, for which the Governor will provide silver.

Dr. Jan Karel van den Broek, 1853

Van den Broek left Dejima in 1857. He was replaced by J. L. C. Pompe van Meerdervoort (1829–1908) who continued the photography lessons. His students included Hikoma Ueno (上野彦馬, 1838–1904), one of the first professional Japanese photographers, and Kuichi Uchida (内田九一, 1844–1875), who in 1872 (Meiji 5) became the first person to officially photograph Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken.

The next important step in Japan’s mastery of photography was the arrival of the pioneering Swiss photographer Pierre Joseph Rossier (1829–1886). Commissioned by the London based firm Negretti and Zambra to shoot a set of the newly opened country, he arrived in Japan in June 1859 (Ansei 6).

Rossier helped the photography students in Nagasaki overcome the last remaining obstacles. He even sold some of them lenses, chemicals and albumen paper.12

This instruction, and the opening of Yokohama and Nagasaki to international trade, was the tipping point. From this moment on—exactly 20 years after Daguerre’s announcement—photography started to spread throughout Japan.

In a 1877 (Meiji 10) letter to the British Journal of Photography, Samuel Cocking (1845–1914), a British merchant in Yokohama who imported photographic supplies, noted that Tokyo already counted 240 photographers, with an equally substantial number of photographers “in nearly every town throughout the interior.”13

These photographers mainly serviced the domestic market for portrait photos. But there was another important market, visitors from the U.S. and Europe desiring memories of their once-in-a-lifetime tour to far-away Japan. Although this market was much smaller, it was enticingly lucrative—many visitors had deep pockets.

As the country had just opened its borders after more than two centuries of seclusion it was seen as exotic and mysterious. Western visitors wanted to share that experience with friends and family and photos were perfect for that.

It is in this market of souvenir photos that hand coloring would develop and play a decisive role.

Continue to Part 2 : Color as a Competitive Tool.

Schwartz, Joan M. (2000). ‘Records of Simple Truth and Precision’: Photography, Archives, and the Illusion of Control. Archivaria 50 (November), 6. Retrieved on 2023-03-22.

Worswick, Clark (1979). Japan Photographs 1854—1905. New York: Penwick Publishing Inc. and Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 129.

Gary W. Ewer, ed. The Daguerreotype: An Archive of Source Texts, Graphics, and Ephemera, Elizabeth Barrett, ‘wonderful invention of the day,’ 7 December 1843. Retrieved on 2023-03-16.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Photography in Japan 1853–1912. Tokyo, Rutland, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 24.

Himeno, Junichi (2005). Encounters with Foreign Photographers: The Introduction and Spread of Photography in Kyūshū in Reflecting Truth: Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 19.

ibid, 20.

文化庁文化財第一課歴史資料部門・重要文化財の写真 Retrieved on 2023-03-16.

Van den Broek, Jan Karel (1893). Uit de laatste dagen van het gesloten Japan, door den heer J. K. van den Broek. Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië, 22e jaargang, Eerste aflevering, Januari 1893, 6. Retrieved on 2023-03-22.

“De Japansche bevolking bevalt mij bij uitnemendheid: het is een schrander en vroolijk volk; zij willen veel weten en belegeren den geheelen morgen mjn huis; somtijds ontvang ik meer dan 20 Japanners en meestal een paar dokters. Gij kunt u geen denkbeeld vormen van de zonderlinge vragen, die zij mj doen; dan moet ik als chemicus optreden, dan weder als natuurkundige, vervolgens als artillerist.”

Moeshart, Herman J. (2009). Dr. Jan Karel van den Broek as Teacher of Photography, Old Photography Study No. 3, 16.

Van den Broek, Jan Karel (1893). Uit de laatste dagen van het gesloten Japan, door den heer J. K. van den Broek. Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië, 22e jaargang, Eerste aflevering, Januari 1893, 6. Retrieved on 2023-03-22.

Mac Lean, J. (1978). The Significance of Jan Karel van den Broek (1814-1865) for the Introduction of Western Technology into Japan, Japanese Studies in the History of Science (16), History of Science Society of Japan 1978-03, 81. Retrieved on 2023-03-23.

ibid, 83–84.

Moeshart, Herman J. (2009). Dr. Jan Karel van den Broek as Teacher of Photography, Old Photography Study No. 3, 14.

“Keisai” refers to Yoshio Keisai (吉雄圭斎, 1822–1894) one of the first principals of what is today the Nagasaki University School of Medicine. In 1857 (Ansei 4), the education of western-style medicine was started by Dutch Naval doctor Johannes Pompe van Meerdervoort (1829–1908). This is considered to be the founding of what is now the Nagasaki University School of Medicine. On Pompe van Meerdervoort’s request the first modern Western-style hospital in Japan was built in 1861 (Man’en 2/Bunkyū 1), the Yojosho (養生所). It featured educational facilitates known as the Ikagusho (医学所). These were consolidated and renamed Seitokukan (精徳館) in 1865 (Genji 2/Keiō 1). Keisai was the principal of the Seitokukan (精徳館執事, Seitokukan Chamberlain) from March 2, 1868 (Keiō 4) through October 25, 1868 (Meiji 1).

Himeno, Junichi (2005). Encounters with Foreign Photographers: The Introduction and Spread of Photography in Kyūshū in Reflecting Truth: Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 22.

For more about Pierre Rossier, see Pierre Joseph Rossier (1829-1886) – Pioneer Photographer In Asia by Terry Bennet.

Cocking, S. (1877). Notes from Japan. The British Journal of Photography, No. 884, Vol. XXIV, April 13, 1877, 173–174. Retrieved on 2023-04-03.

Very interesting. I have a feeling that you could go into greater detail regarding the influence of the Shimazu Clan in Kagoshima. While I live in a different part of Kyushu, during a visit to Kagoshima last year I was amazed to learn how this pioneering family helped usher Japan into the modern industrial world. Thus, it was no surprise to learn from you how they were involved with photography early on.