Spotlight • Empire of Color (3)

How 19th century Japanese artists mastered the art of hand colored photography — How colorists worked.

Read on the site | Comment | Support

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4

The Art of Coloring

Surprisingly little is known about the colorists, how they worked, who they were, what kind of a background they had, or even how many there were.

Anecdotal information suggests that there may have been many hundreds of them. When Boston-based publisher J.B. Millet imported over 400,000 hand colored photographs from Japan in 1896 (Meiji 29) for the multi-volume Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese, more than 350 “native artists” were engaged.1 Likely many of them were colorists.

In the late 1880s, Italian Photographer Adolfo Farsari wrote his sister that he employed forty people, of whom sixteen were colorists.2 He explained that he first made sure that an applicant could paint Japanese style, and then trained the person for two to four months.3

Coloring was precise and time-consuming work. When Burton—who was so impressed by Japan’s hand colored prints—visited Farsari’s studio, he was told that the colorists took several hours to color a single photograph:4

In the Gallery of A. Farsari Co. I had the pleasure of seeing the native artists at work. They were to be seen busily engaged in a large room, each artist in the position almost universally adopted by a Japanese for his work, namely, squatting on a straw mat.

…

Farsari’s artists were very slow and careful in their work. He informed me that he was satisfied if each coloured two or three prints in a day, This allows time enough for each print to be really well coloured, and, indeed, I have seen no better work in the way of coloured photographs anywhere than some of Farsari’s productions.

William Kinnimond Burton, 1887

If two to three prints a day seems slow, a Yokohama court case from 1878 (Meiji 11) over the unpaid coloring wages of the German artist Hermann Friebe suggests that in some cases coloring could take a lot longer. Austrian photographer Stillfried, who appeared as an expert witness, stated that the coloring of the two photos presented in the case “would occupy a skilled workman 20 days.”5

Likely, mass production was more common—especially during the fierce competition of the 1880s and 1890s. Some sources claim that Tamamura, who competed mostly on price, had his colorists tint over 60 images a day. Although this sounds extreme, Farsari wrote his sister that one of his Japanese competitors worked this way.

The British naturalist Richard Gordon Smith (1858–1918) who travelled in Japan between 1898 (Meiji 31) and 1907 (Meiji 40) explicitly complained about bad coloring by the Tamamura studio in his diary. It launched him into a bigoted rant about the Japanese which is painful to read.6

Farsari’s advertising actually stressed the unreliable quality of other studios. An 1893 ad claimed that his studio had “the only photographers that deliver pictures equally as well painted as those exhibited in our sample albums or frames.”7

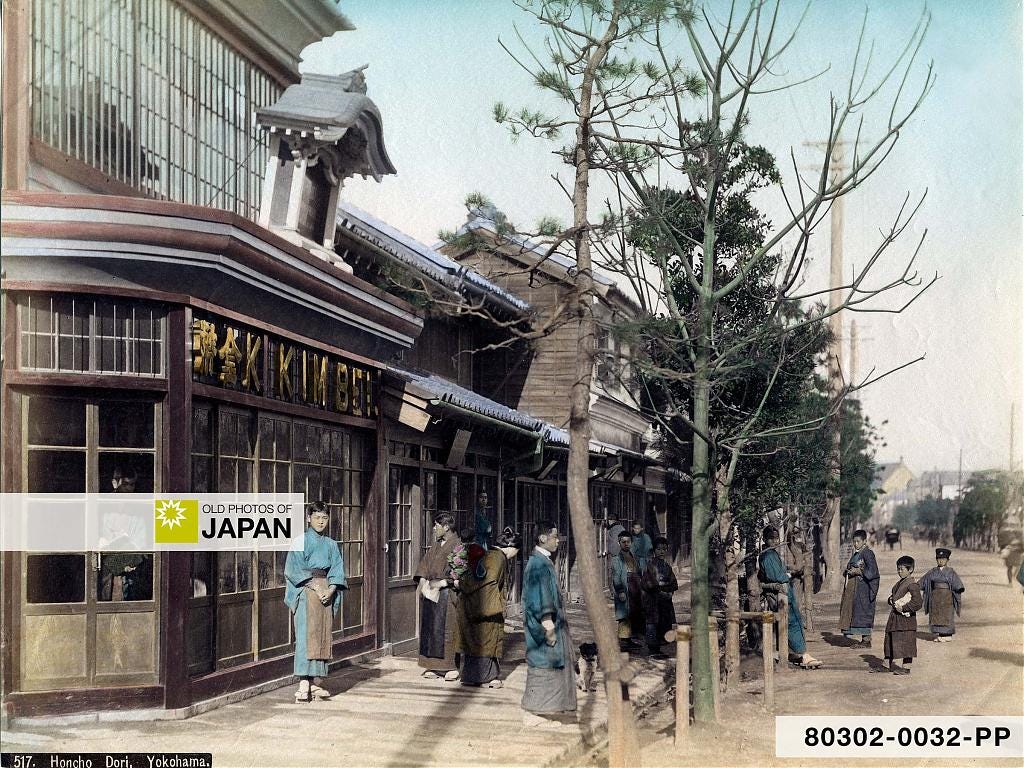

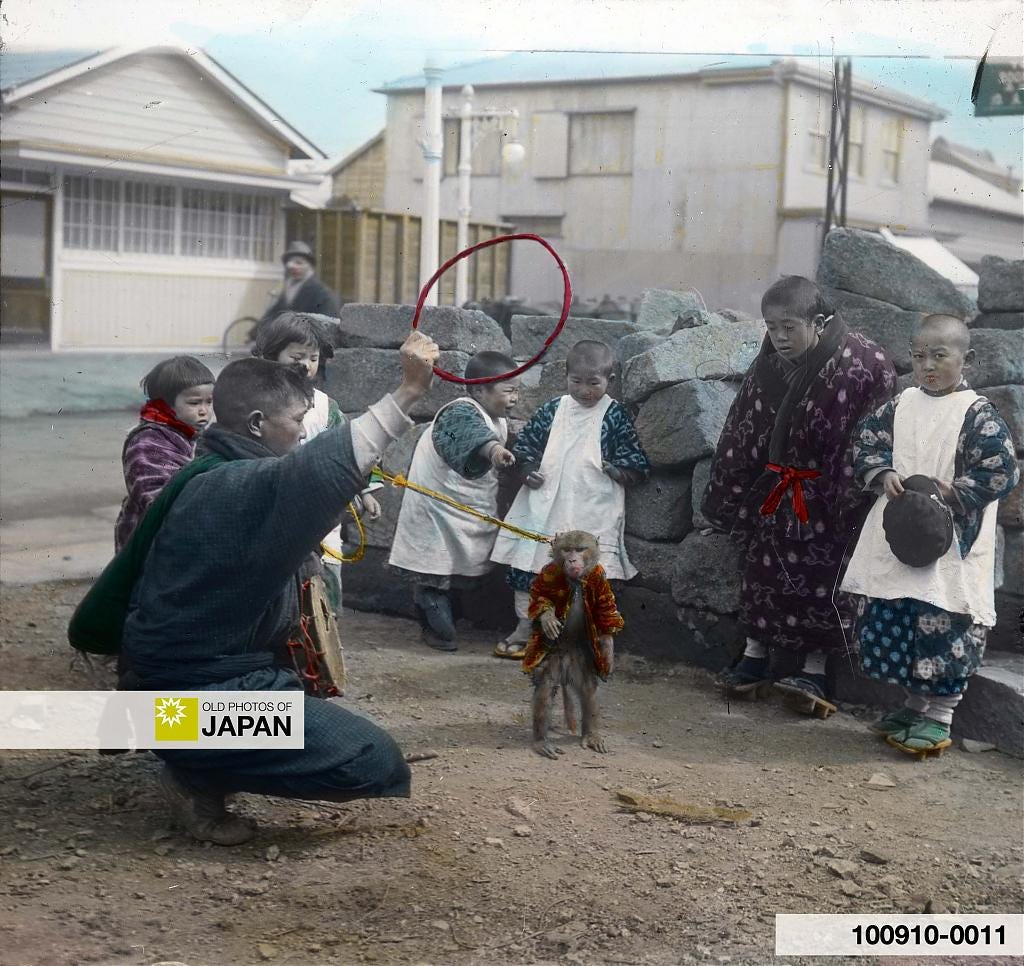

However, as the following images illustrate, Kimbei and later photographers like Enami and Takagi also produced extremely impressive coloring.

Even less is known about the coloring process itself. As far as I have been able to ascertain no laboratory research has been done on the materials used, and no memoir or letters by Japanese colorists are known that explain how they worked.

It is believed that water-soluble vegetable pigments as well as synthetic colors were used. These offered greater transparency than the oil paints regularly used in Western countries.8

If you put a colorized European photograph next to a Japanese one, you see the difference immediately. In Japanese photographs the colors are soft, transparent, and realistic. The color is not on top of the photograph but has become part of it. The photo below of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert clearly shows the difference.

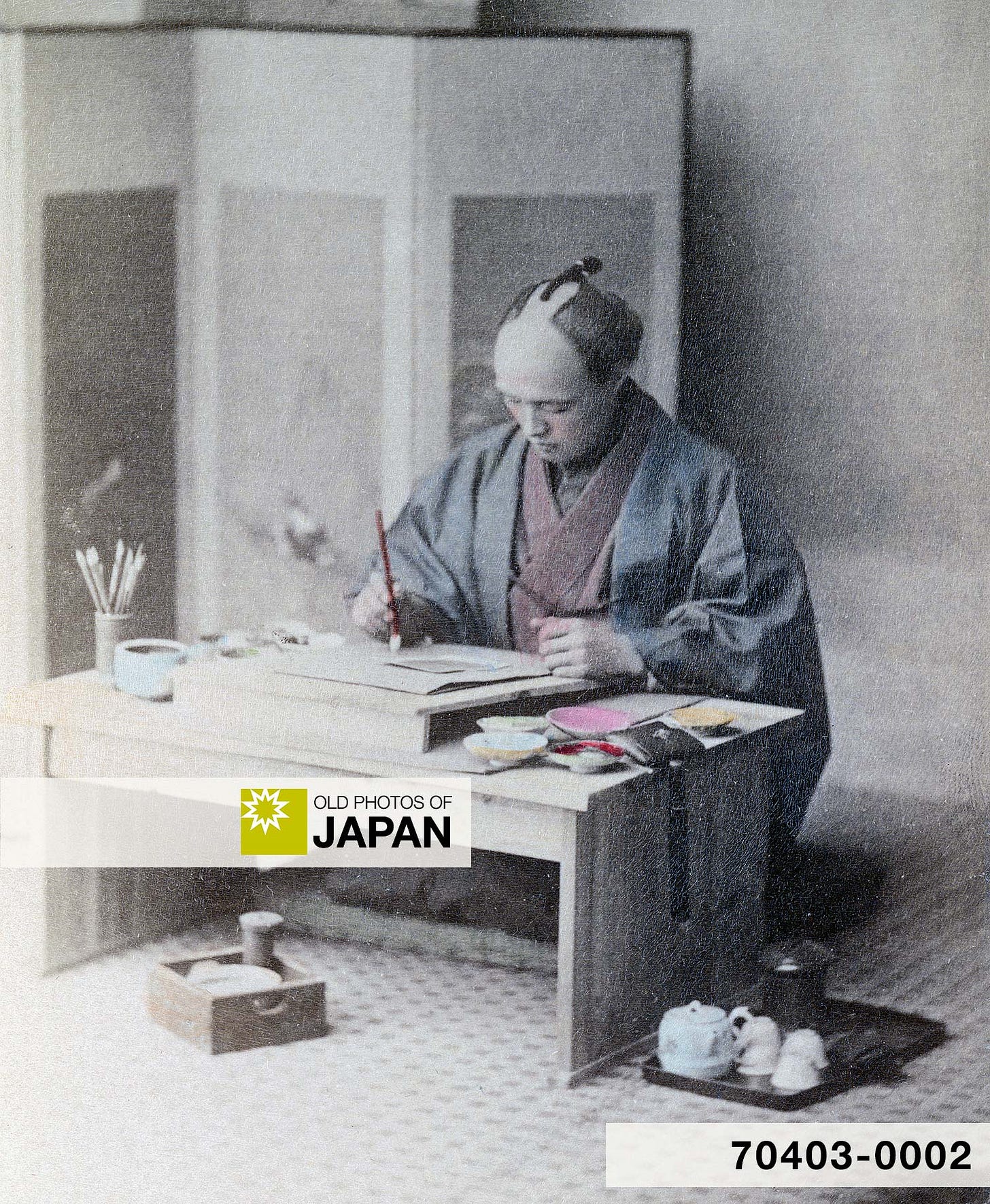

As Burton described, Japanese colorists sat at low tables “squatting on a straw mat.” The colors were mixed with water in small porcelain saucers, one for each color used in the print. Some studios may have used production lines in which each colorist applied specific colors, then passing the print to the next colorist.

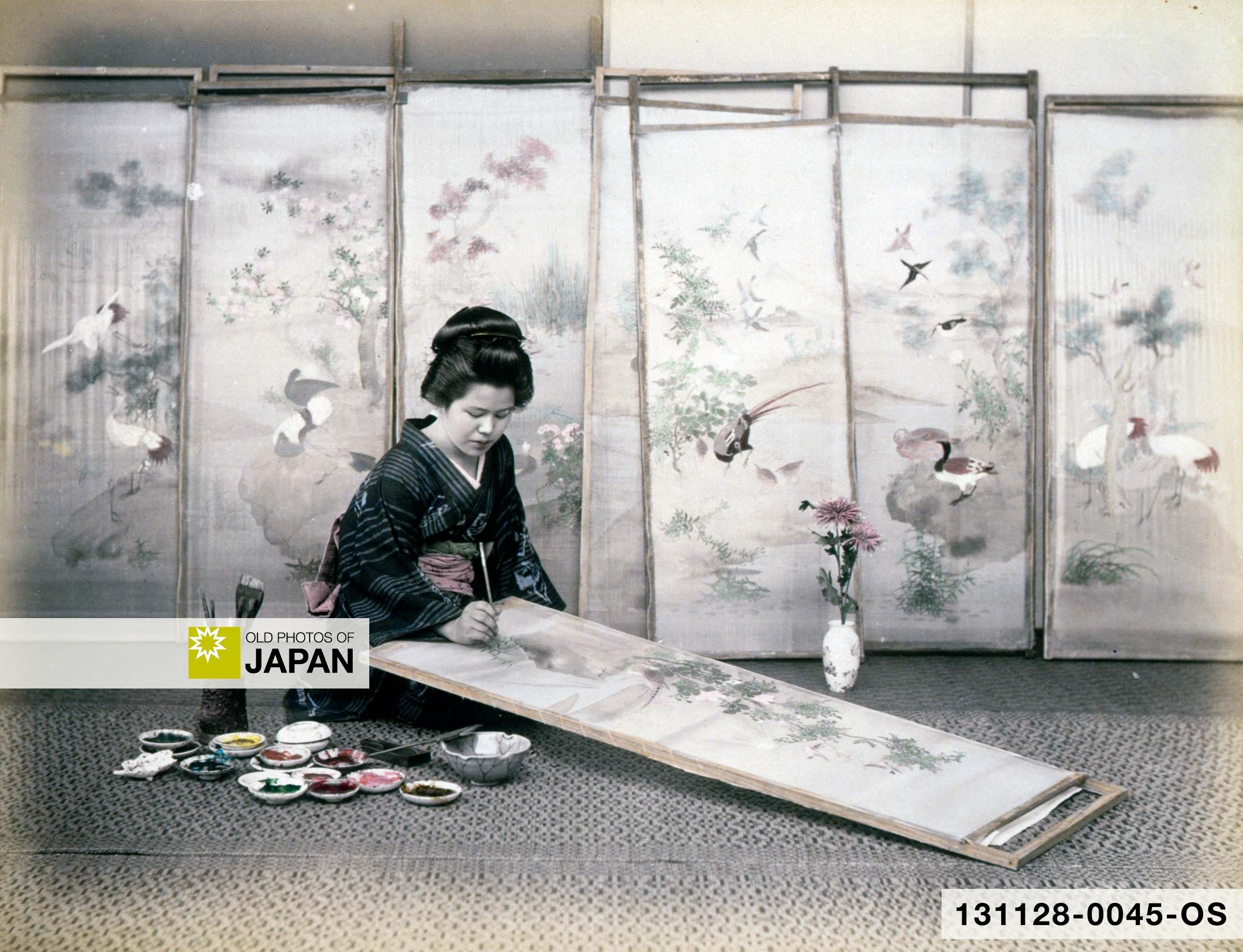

Below are two staged photographs of Japanese colorists “at work.” Notice that in the second photo the colorists have clipped the prints onto boards. Albumen prints used extremely thin paper that easily curled.

Especially striking in both photographs is the large number of color dishes. In the photo below there are nine. In the photo below that, the colorist on the right appears to have at least twelve saucers on his table.

This working method is basically identical to the way Japanese artists traditionally worked. In the image below of a female artist painting a screen, a similar large number of the same kind of small dishes can be seen.

We know from a letter that Farsari wrote to his sister that the coloring started with applying water to make the paper damp. Although the albumen prints are shiny, no varnish was used:9

There is no secret about this painting. Apply water to the photograph with a brush until the paper is damp and then paint using rubber colors. No varnish. The shining effect is produced by the paper. Also monochrome photographs are slightly shining.

Adolfo Farsari, 1889

A wide range of brushes were used for the coloring. The finest brush could have just a single strand of hair. Detailed work would require a magnifying glass. This was especially necessary for glass lantern slides and stereoviews. Some of the colored details on such media were a millimeter in width or less. The samples below display the masterful artisanship and steady hand involved in this work. Even when enlarged the details are clean and clear.

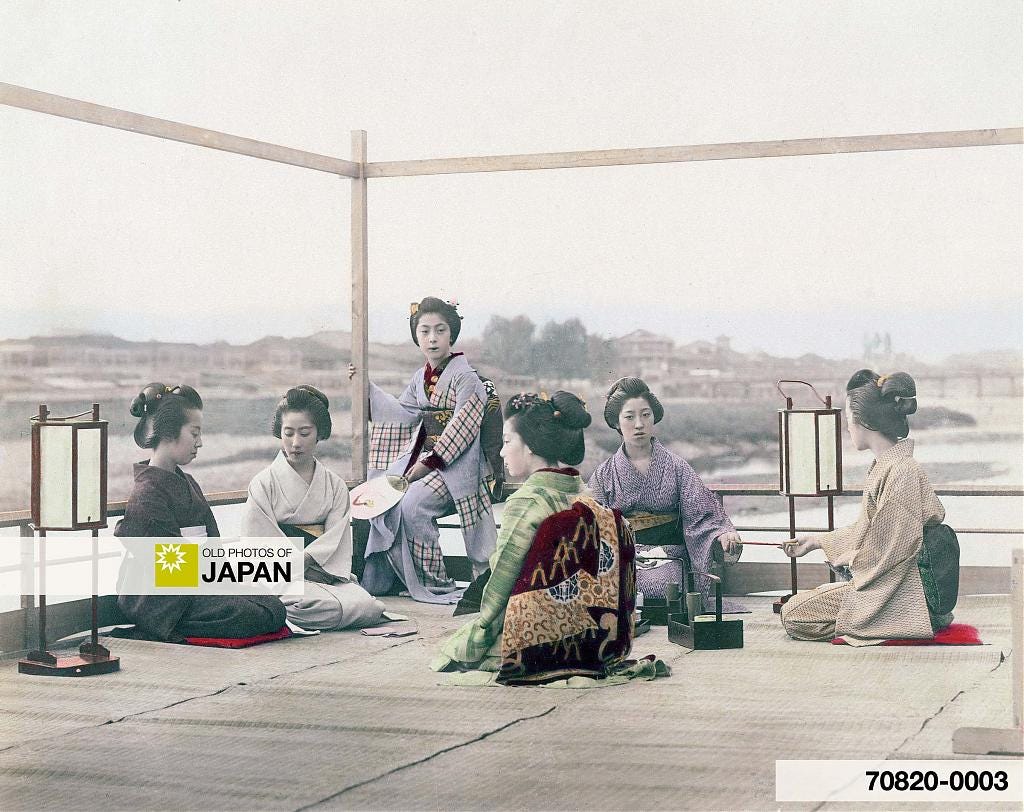

Especially notice the gradation in color in the obi the woman on the right wears in the image below. It almost imperceptibly darkens from top to bottom, and left to right. On the original glass slide the obi measures only about a centimeter in width.

Some images—like the one from the Enami studio below—required the coloring of countless small details. Notice how the hanao (鼻緒, cloth straps) of the footwear are perfectly colored in a variety of colors. On the original glass slide these measure less than a millimeter in width.

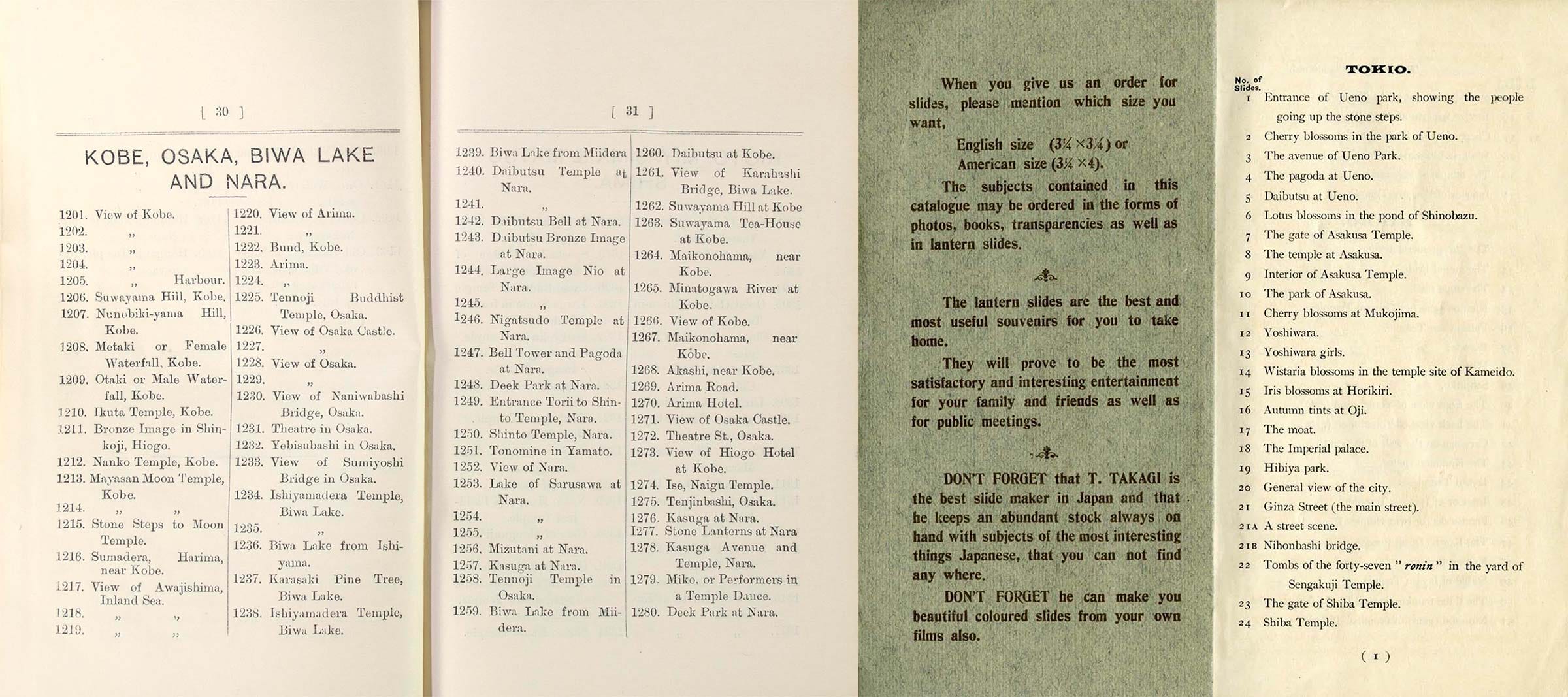

Customers selected the images from framed samples, display albums, or printed catalogues with numbered photo titles. Tourists usually did so before they started out on their tour through Japan, selecting images that corresponded with their itinerary. Studio catalogues were therefore organized by location.

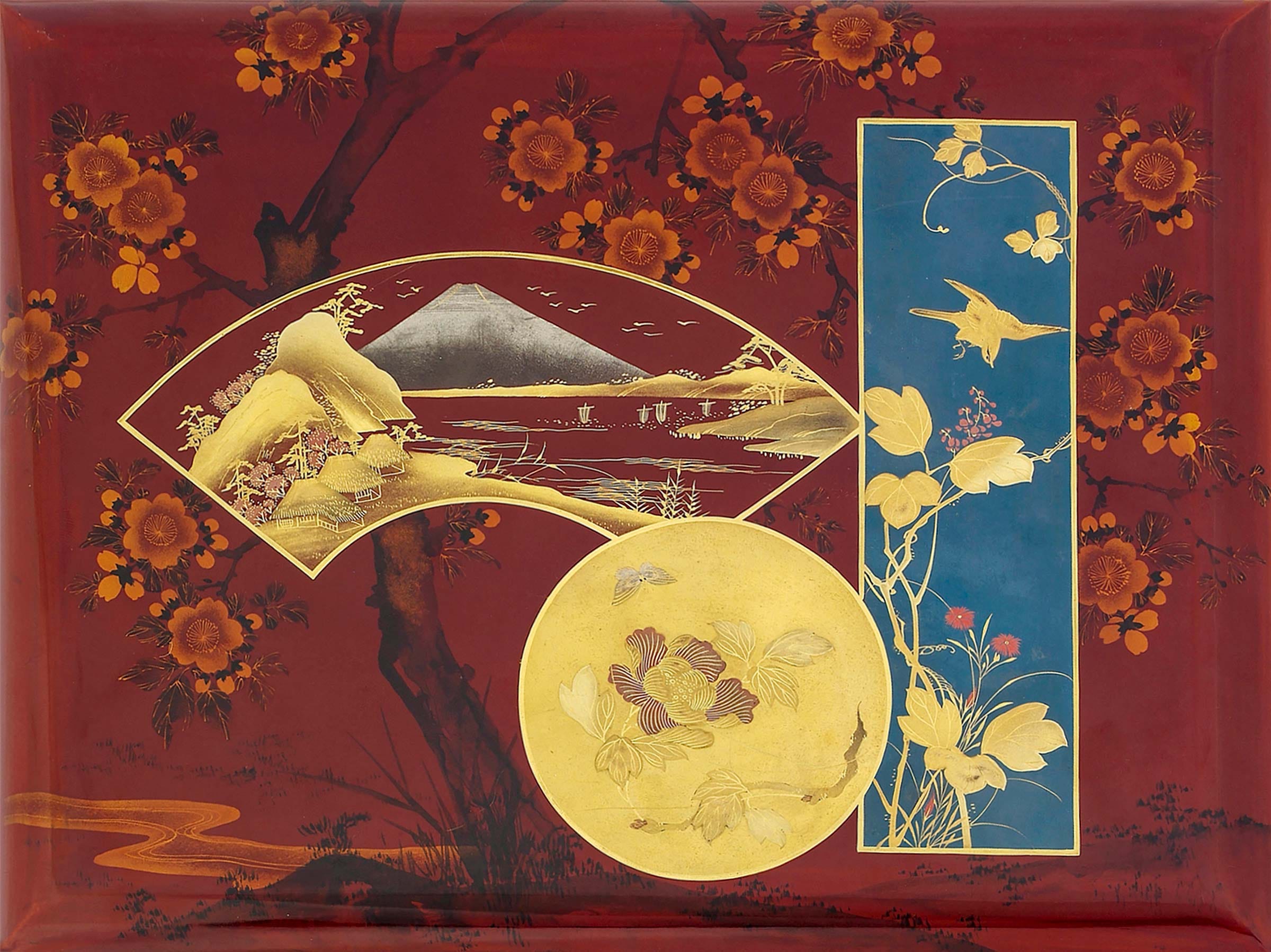

Prints were sold individually or mounted in albums of 50 or 100 photos. The most exclusive of these albums featured magnificent lacquered covers, often inlaid with rich ivory. Occasionally even gold leaf was applied. Farsari exclusively contracted a craftsman to create his studio’s lacquered covers.10

The most common print size in these albums was 8×10 inches (approx. 20×25 cm).

The Question of Authenticity

Because the photographs were hand colored, we need to answer an important question: how accurate were these colors? Are they a true representation of the scene that the photographer saw?

According to research by Australian photo historian Luke Gartlan, Stillfried’s colorists “followed a strict prototype to ensure uniform production standards.”11

An 1893 ad for the Adolfo Farsari studio specifically states that “the colors were carefully noted at the time that photos of temples and other structures were taken, and we are the only ones who paint them as they really are.”

Even if all studios followed such strict procedures—and the Farsari ad claims that this was not the case—photographs from one studio regularly ended up in the hands of other studios. Stillfried, Farsari, Kimbei, and other studios all sold Beato prints for example. By necessity they would have had to apply their own color scheme. One actually sees variations in the colors used for a particular photograph, even if produced by the same studio.

These differences can be quite pronounced, but usually they are rather subtle. Let’s have a look at an example. Below are two lantern slides and a stereoview from the same negative by Nobukuni Enami, whose trade name was T. Enami.

Even when each image is colored only slightly differently—as in this example—the overal effect can result in a different impression. In this case, the stereoview is brighter and feels slightly more cheerful than the glass slides.

The colors of some of the clothing differ per image, so we do not know the true colors of the girls’ clothing. But anyone familiar with clothing from this period will recognize that the colors are true to the era. The different greens of the bushes are also all possible, depending on the season, weather, and time of day.

Are the colors a true representation of the scene? — No, different images show different colors. Are they a true representation of Japan at that specific time period? — Yes, the colors in the photographs generally were the colors of Japan at the time the scenes were photographed.

One could perhaps call this selective authenticity. The colors may not perfectly represent the scene, but they do represent the reality of the period.

A contemporary and reliable witness actually acknowledged this in his writing, famed British author Rudyard Kipling, who wrote The Jungle Book:12

A coloured photograph ought to be an abomination. It generally is, but Farsari knows how to colour accurately and according to the scale of lights in this fantastic country. On the deck of the steamer I laughed at his red and blue hill-sides. In the hills I saw he had painted true.

Rudyard Kipling (1889)

We tend to think of photographs as identical copies. But each hand colored photo is really an original, literally and figuratively touched by several artists. The colors they applied are unlikely to correspond perfectly to what the photographer saw. Yet, when the coloring was done well it is in effect an authentic representation of the colors seen in Japan at the time that the photographs were taken.

Continue to Part 4 : Why Japan became the empire of hand colored photography.

Notes

Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 338. According to Gartlan, 151,500 large format photographs and 254,000 small format photographs were exported for the 37,750 volumes of Japan Described and Illustrated by the Japanese. Some sources claim that more than one million hand-colored albumen prints were produced for the books.

Mundy, Arthur J. (1897). Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese. Boston: J.B. Millet Company, vii. In the introduction to the Shogun Edition, Mundy writes, “The photographs are all made and colored by hand in Japan, over three hundred and fifty native artists having been specially engaged for this purpose.”

Winkel, Margarita (1991). Souvenirs from Japan: Japanese Photography at the Turn of the Century. London: Bamboo Publishing Ltd., 29. Exporting hand colored photographs was an industry. Winkel mentions that 24,923 photographs were exported to the U.S.A. and Europe in 1897, and 20,242 in 1900.

Beretta, Lia (1996). Adolfo Farsari: An Italian Photographer in Meiji Japan in The Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Fourth series, Vol. 11, 40, 44.

ibid, 41.

Burton, W.K. (1887). The British journal of photography: Photography in Japan, August 19, 1887, 518, 519. Retrieved on 2023-04-12.

Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 250.

Gordon Smith, Richard (1986). Travels in the Land of the Gods (1898-1907): The Japan Diaries of Richard Gordon Smith. New York: Prentice-Hall Press, 48.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Old Japanese Photographs: Collectors’ Data Guide. Bernard Quaritch Ltd., 250.

Wakita, Mio (2013). Staging Desires: Japanese Femininity in Kusakabe Kimbei’s Nineteenth Century Souvenir Photography. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, 45.

Beretta, Lia (1996). Adolfo Farsari: An Italian Photographer in Meiji Japan in The Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Fourth series, Vol. 11, 42.

ibid, 43.

Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 205.

Kipling, Rudyard; Cortazzi, Hugh; Webb, George (1988). Kipling’s Japan: Collected Writings. London: The Athlone Press, 131.