Spotlight • Empire of Color (2)

How 19th century Japanese artists mastered the art of hand colored photography — Color as a competitive tool.

Read on the site | Comment | Support

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4

The Question of Color

We tend to think of early photography as a monochrome affair, but from the very beginning color was a concern and expectation. Already in 1841, only two years after the daguerreotype had been announced, British scientist Robert Hunt (1807–1887) covered the issue of color in A popular treatise on the art of photography.

An article in the Journal of the Photographic Society of London of August 21, 1854 vividly illustrates how acutely the lack of color was felt in portraits:1

The want of colour is chiefly felt in portraits; this deficiency imparts a cold and almost cadaverous air; it renders the likeness less perfect, and often gives an appearance of greater age.

Journal of the Photographic Society of London, 1854

Practical color reproduction however turned out to be extremely difficult. So, photographers were instructed to hand color their images. The first American patents for hand coloring daguerreotypes were granted only three years after Daguerre’s announcement.2 Over the next century a seemingly endless stream of manuals and products were created to hand tint photographs.3

Once again, it took some time for this development to reach Japan. The first known reference to a hand colored photograph of Japan is an 1860 ad in The Times by Negretti and Zambra for a stereoview taken by Rossier.4

Only after the arrival of Italian-British photographer Felice Beato (1832–1909) in 1863 (Bunkyū 3) did coloring photographs really take off in Japan. He appears to have started coloring his prints on a large scale in the mid to late 1860s.

When Beato settled in Yokohama he had already built quite a name and career as a pioneering war photographer of the Crimean War (1853–1856), the Indian Rebellion (1857–1858), and the Second Opium War in China (1856–1860).

He was the first photographer to show the carnage of war, photographing ruins full of corpses, albeit only of the enemy. At a time when mainly soldiers knew what battle really looked like, observers were simultaneously shocked and fascinated:5

Signor Beato’s photographs, taken during the Chinese war and the Indian mutiny, are now on view at Mr. Hering’s, in Regent Street, London. The collection not only gives views of all the more interesting and best known spots connected with the mutiny and the war, some of which are panoramic, but also depicts the terrible sight of a battle field as it remained after victory and defeat; showing the dead strewn thickly about the field they fought to gain, their sun-dried corpses and bleached bones showing horribly distinct, and all the varied circumstances of their retributive slaughter.

British Journal of Photography, 1862

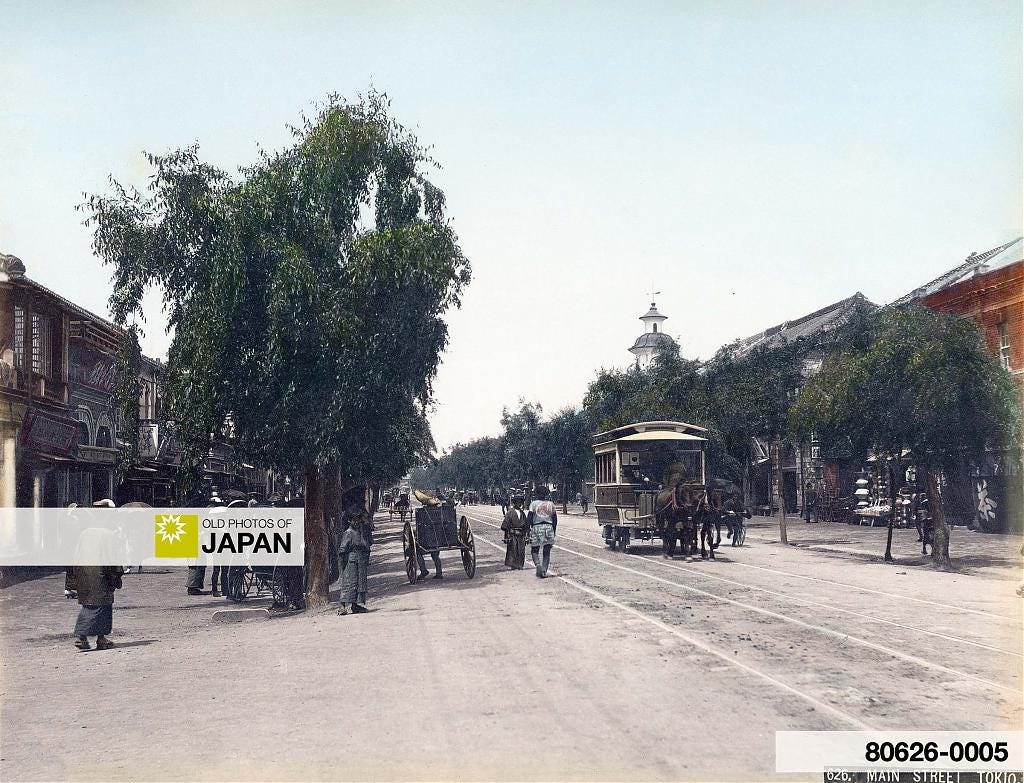

Beato had an enormous influence on Japanese photography aimed at the international market. In 1868 (Keiō 4) he was the first to sell photographic souvenir albums in Japan which soon became a staple product. The topics and themes that he chose, and even his photographs themselves, were used for decades by many photographers who came after him.

His work was also regularly used as the basis for engraved illustrations in Western newspapers, magazines, and books. Swiss envoy Aimé Humbert (1819–1900) used over a hundred Beato images for his celebrated work Le Japon illustré (Japan and the Japanese illustrated). It is no exaggeration to say that the popular image of traditional Japan was shaped by Beato.

One of Beato’s most consequential contributions to Japanese photography might have been the hand coloring of photographs. He divided his photographs into topographical views and portraits, the latter often occupational views staged in the studio. These were confusingly referred to as costumes at the time.

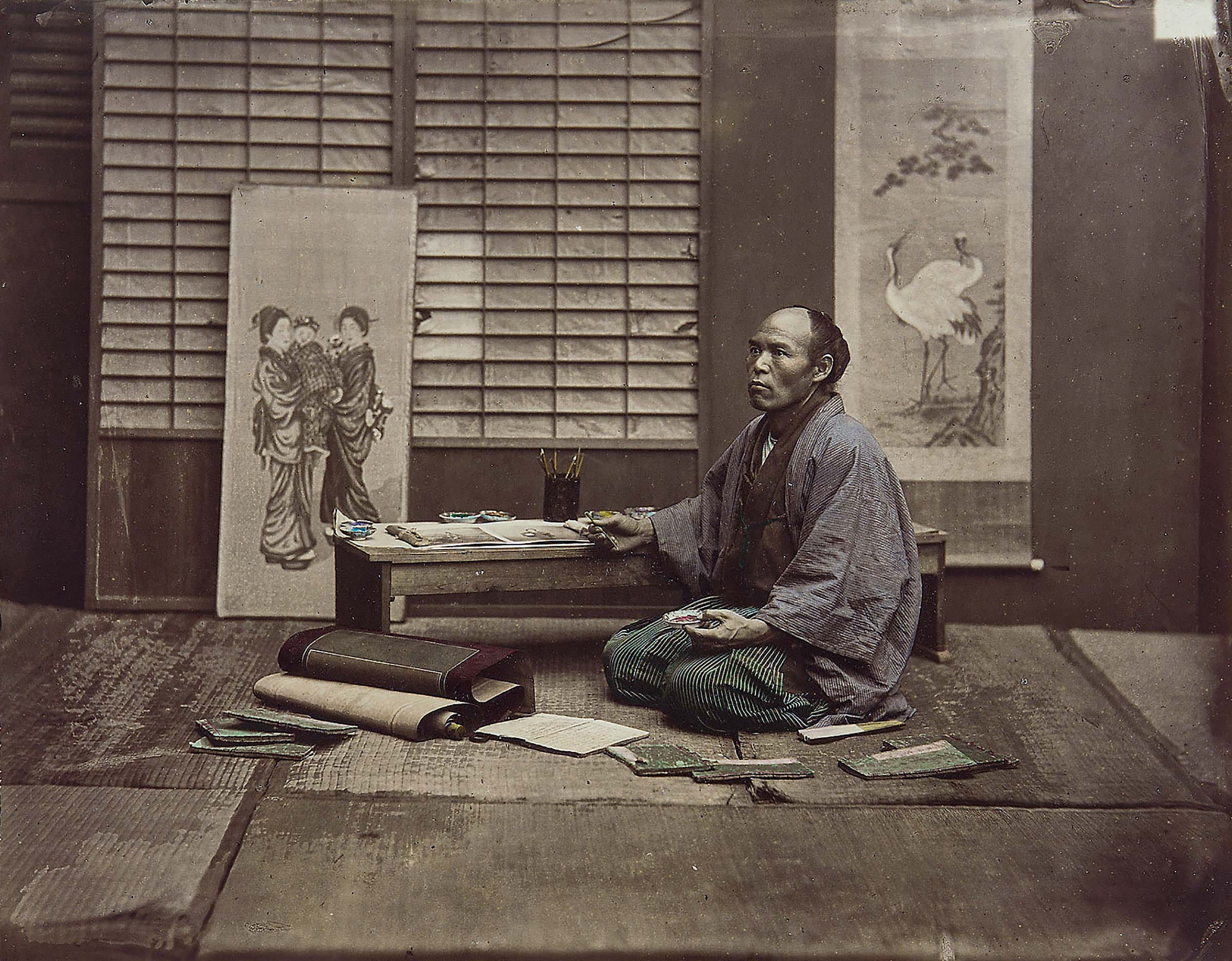

While the topographical views were generally left untinted, the costumes were almost always hand colored. It is believed that this coloring was initially done by Beato’s business partner, the British artist Charles Wirgman (1832–1891). Soon after, Japanese artists were hired to perform the task. By 1872 (Meiji 5), Beato employed four Japanese colorists (as well as four Japanese photographers and an assistant named H. Woolett).6

One of Beato’s colorists was the artist Kimbei Kusakabe (日下部金兵衛, 1841–1934), who later became a successful photographer in his own right.7 Kimbei—he is known by his first name—started to work for Beato in the late 1860s.8

In 1987 (Shōwa 62), the Japanese photo researcher Yōichi Kuwajima (桑嶋洋一, 1935–2020) found a photo of a colorist in the Beato studio who is believed to be Kimbei.9 The Japanese colorists have generally remained anonymous and faceless, so this was an astounding discovery.

Spreading Color

The hand coloring techniques pioneered by Beato were adopted by all other photographers catering to the international market. An especially influential one was the Austrian photographer Baron Raimund von Stillfried-Ratenicz (1839–1911) who was mentored by Beato. Stillfried started his own studio in 1871 (Meiji 4) and purchased Beato’s studio and inventory in 1877 (Meiji 10), several weeks after his own studio had burned down.

Stillfried continued and expanded on Beato’s themes and subjects, and also Beato’s custom of creating photographic albums which were separated into sections of untinted topographical views and hand colored costumes. But he created his own style by applying the principles then dominating the European fine arts.

Stillfried did not just adopt Beato’s practice of hand coloring photographs, it seems he even hired Kimbei, as well as other Japanese colorists and assistants.10 Business flourished—at the studio’s peak he employed 39 Japanese assistants.11

Many of these assistants would eventually open their own photography studios. Some of them—like Kimbei and Shūzaburō Usui (臼井秀三郎)—also created hand colored photographs for the tourist market.12

Japanese studios slowly started to encroach on the hand colored photo market pioneered by Beato and Stillfried from the second half of the 1870s. Usui first advertised his studio in 1875 (Meiji 8), while Kimbei started his business sometime between 1878 and 1880 (Meiji 11–13).13

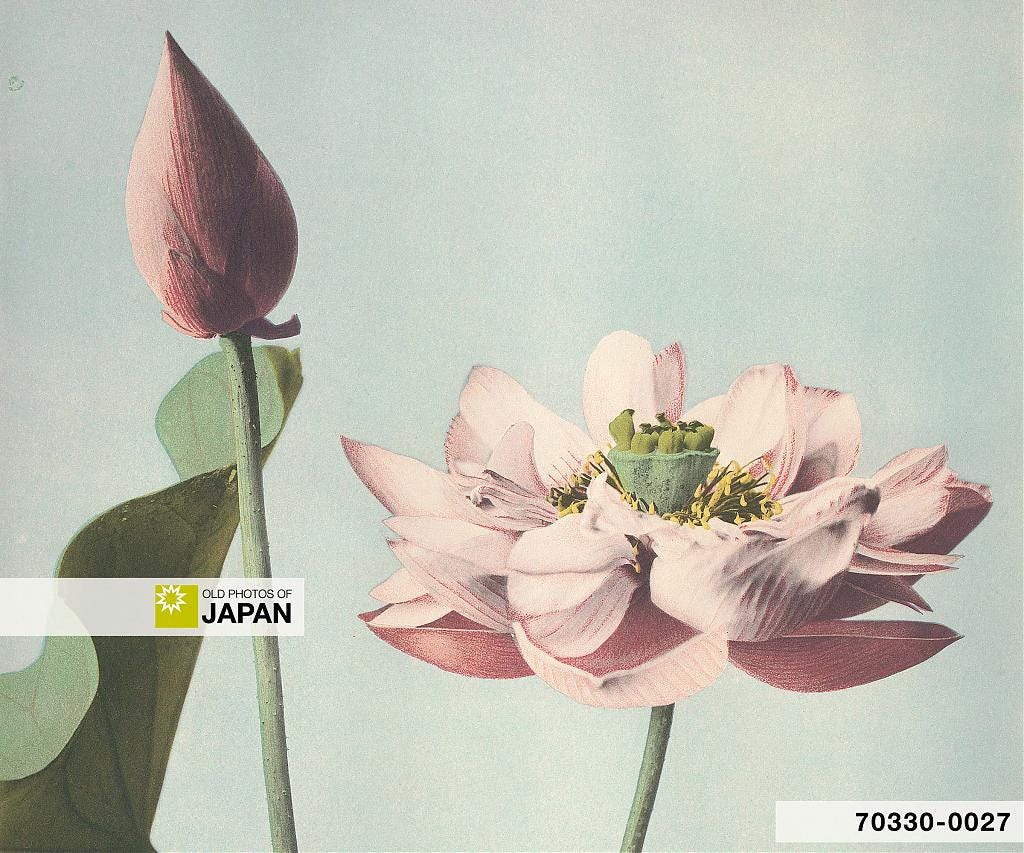

They were not the only ones. In 1883 (Meiji 16), Kōzaburō Tamamura (玉村康三郎, 1856–1923?) opened his Yokohama studio. He would become the commercially most successful Japanese photographer of the 19th century.14 Kazumasa Ogawa (小川一眞, 1860–1929), who pioneered photomechanical printing in Japan and whose colored collotypes of flowers still impress today, opened a studio in Tokyo in 1885 (Meiji 18).15

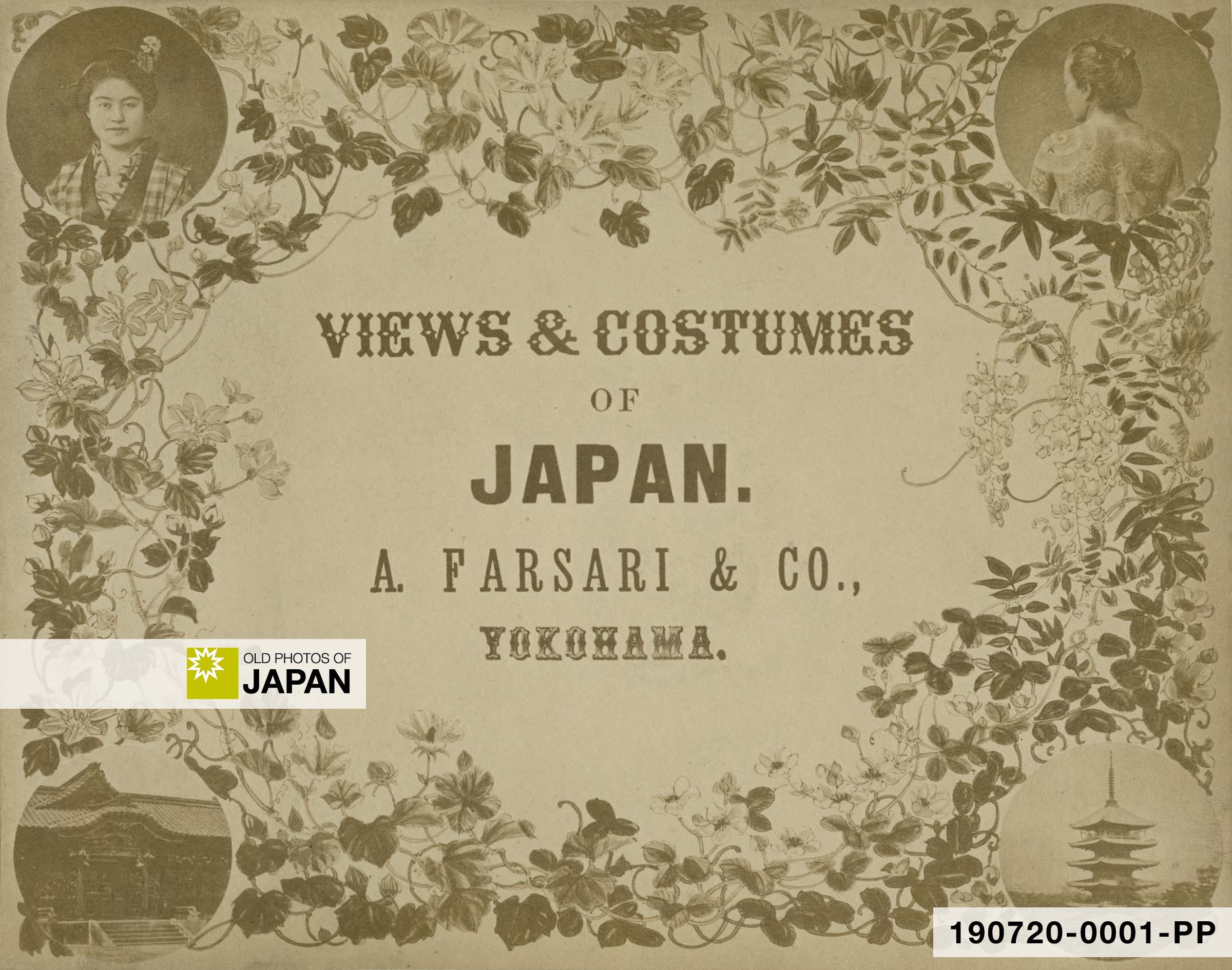

In the same year as Ogawa, the Italian photographer Adolfo Farsari (1841–1898) bought up the studio originally started by Stillfried and located himself next to the famed Grand Hotel in Yokohama, conveniently close to his clientele.16

Nobukuni Enami (江南信國, 1859–1929)—one of the most accomplished photographers of the era, mastering photographic media from prints to lantern slides to stereoviews—established his studio in 1892 (Meiji 25), within a stone’s throw of top earner Tamamura.17

One more major player jumped into the fray. In 1904 (Meiji 37) Teijiro Takagi (高木庭次郎) took over Tamamura’s Kobe branch, publishing gorgeous hand colored lantern slides and collotype books.18 You may remember the three Takagi books I previously introduced: The Rice in Japan, The Ceremonies of a Japanese Marriage, and The New Year in Japan.

Countless other studios were started during the same period. Most quickly failed. This intense competition transformed hand coloring into a crucial competitive tool. Usui’s studio was one of the first to also color topographical views. Other studios followed. By the 1880s colored views had become the norm.19

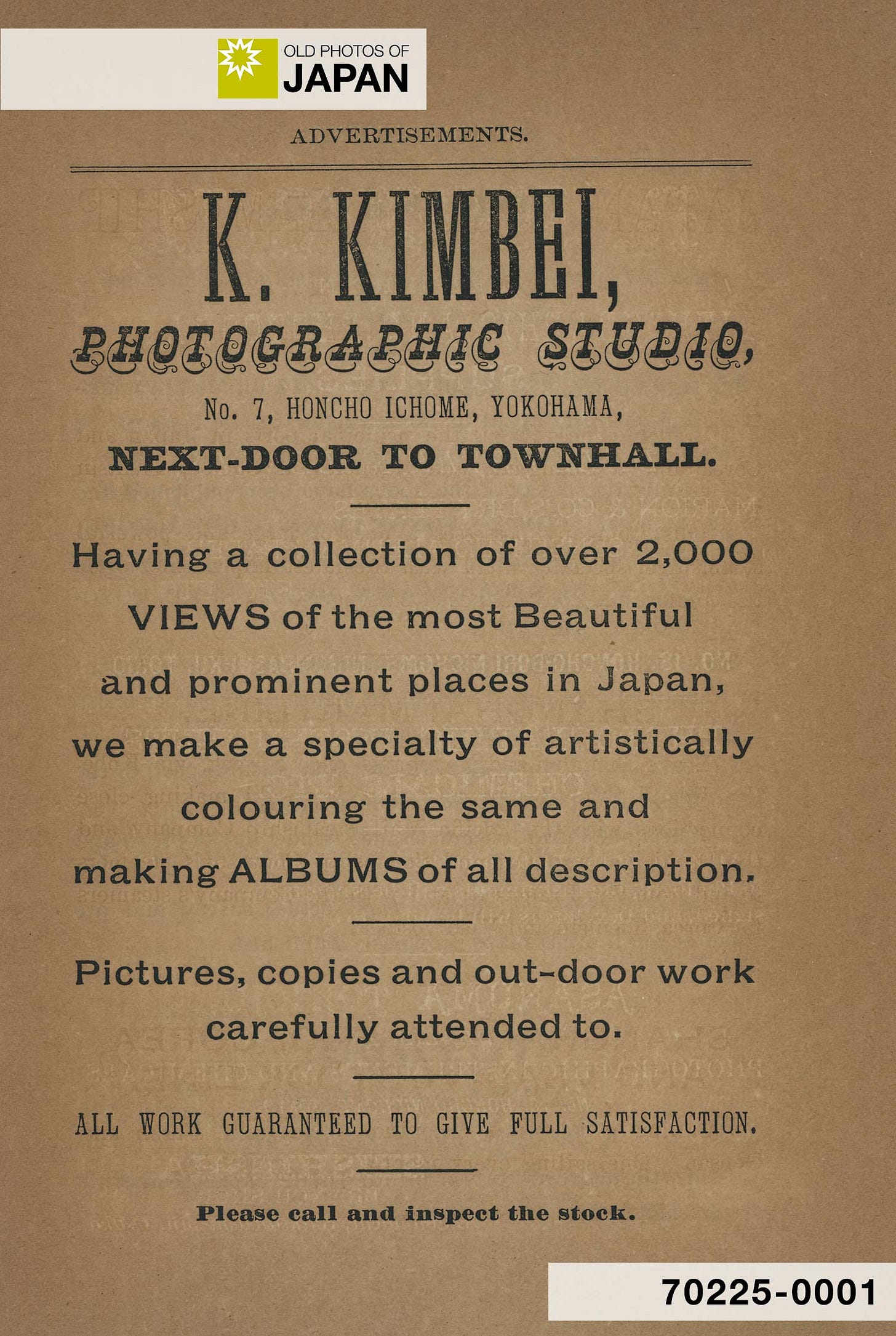

This competition over color is observable in studios’ advertising. Color is still rarely mentioned in ads during the 1880s. But from around 1890 (Meiji 23) it becomes standard. The following ad for the studio of Kimbei Kusakabe in Keeling’s Guide to Japan published in 1890 is an early, and still understated, example.20

Western visitors were simultaneously surprised and delighted by the coloring. One such surprised visitor was Scottish engineer and photographer William Kinnimond Burton (1856–1899) who was hired by the Japanese government to lecture at Tokyo Imperial University. Shortly after his arrival in 1887 (Meiji 20) he shared his impressions in a letter to The British Journal of Photography:21

It is an almost universal practice to colour landscape photographs in Japan. In so great disfavour is the colouring of prints on albumenised paper generally held at home, that it is very difficult to overcome the strong prejudice that one feels against the practice; but it must, on consideration, be admitted that, in Japan, it is at least a much more excusable practice than in England.

Landscape photographs are generally purchased here, by visitors, to take home to give some idea of the country to their friends, and, as a matter of fact, no idea—or, rather, only half an idea—can be given if the element of colour is left out of the pictures. Colour is of importance enough at home; but it is of very much greater importance here, where its vividness is something it is impossible to describe. Especially is this true of the greens. The most gaudy colouring cannot show them as more brilliant than they are.

Then, again, the colouring of photographs has probably fallen into disrepute rather because it has been badly done than because there is anything essentially vicious in a painted photograph, and the Japanese are well known to be most skillful in the use of colours.

William Kinnimond Burton, 1887

Continue to Part 3 : How Colorists Worked.

Notes

Minotto, M. (1854). Method of Colouring11 Photographic Pictures in Journal of the Photographic Society of London, Vol. II. No. 21, August 21, 1854, 21.

Johnston, Cara (2004). Hand-Coloring of Nineteenth Century Photographs. The Cochineal. Retrieved on 2023-03-25.

Lehmann, Ann-Sophie (2015). The Transparency of Color: Aesthetics, Materials, and Practices of Hand Coloring Photographs between Rochester and Yokohama. Getty Research Journal No. 7, 81-96. Retrieved on 2023-03-25.

For the global history of hand coloring photographs, see Henisch, Heinz K; Henisch, Bridget Ann (1996). The painted photograph, 1839-1914: origins, techniques, aspirations. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Old Japanese Photographs: Collectors’ Data Guide. Bernard Quaritch Ltd., 47.

S.T. (1862). Notes of the Month. The British Journal of Photography, No. 169, Vol. IX, July 1, 1862, 257. Retrieved on 2023-03-27.

Iwasaki, Haruko (1988). Western Images, Japanese Identities: Cultural Dialogue between East and West in Yokohama Photography in A Timely Encounter: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of Japan. Peabody Museum Press, 29.

A colorist is called a coloring technician (着色技師, chakushoku-gishi) in Japanese.

Dobson, Sebastian (2004). Yokohama Sashin in Art and Artifice: Japanese Photographs of the Meiji Era. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 28.

中村 啓信 (2006). 明治時代カラー写真の巨人 日下部金兵衛. 国書刊行会, 62–63.

ibid, 60–61.

Gartlan, Luke (2017-07-20), Postcards from a picture-perfect Japan. Retrieved on 2023-04-01.

Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 222–223.

ibid, 223.

Wakita, Mio (2013). Staging Desires: Japanese Femininity in Kusakabe Kimbei’s Nineteenth Century Souvenir Photography. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, 41.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Photography in Japan 1853–1912. Tokyo, Rutland, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 199.

ibid, 211.

ibid, 221.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Old Japanese Photographs: Collector’s Data Guide. London: Bernard Quaritch Ltd., 74.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Photography in Japan 1853–1912. Tokyo, Rutland, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 294.

Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 227.

Farsari, A. (1890). Keeling’s Guide to Japan. Yokohama, Tokio, Hakone, Fujiyama, Kamakura, Yokoska, Kanozan, Narita, Nikko, Kioto, Osaka, Kobe, &c. &c. Kelly & Walsh, Limited: 173.

The British Journal of Photography: Photography in Japan. Burton, W.K. (August 19, 1887). 518, 519. Retrieved on 2023-04-12.