Osaka's Nakanoshima: Small Island, Big Dreams

Stunning vintage photos paired with a rare illustrated map reveal 1920s Osaka

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

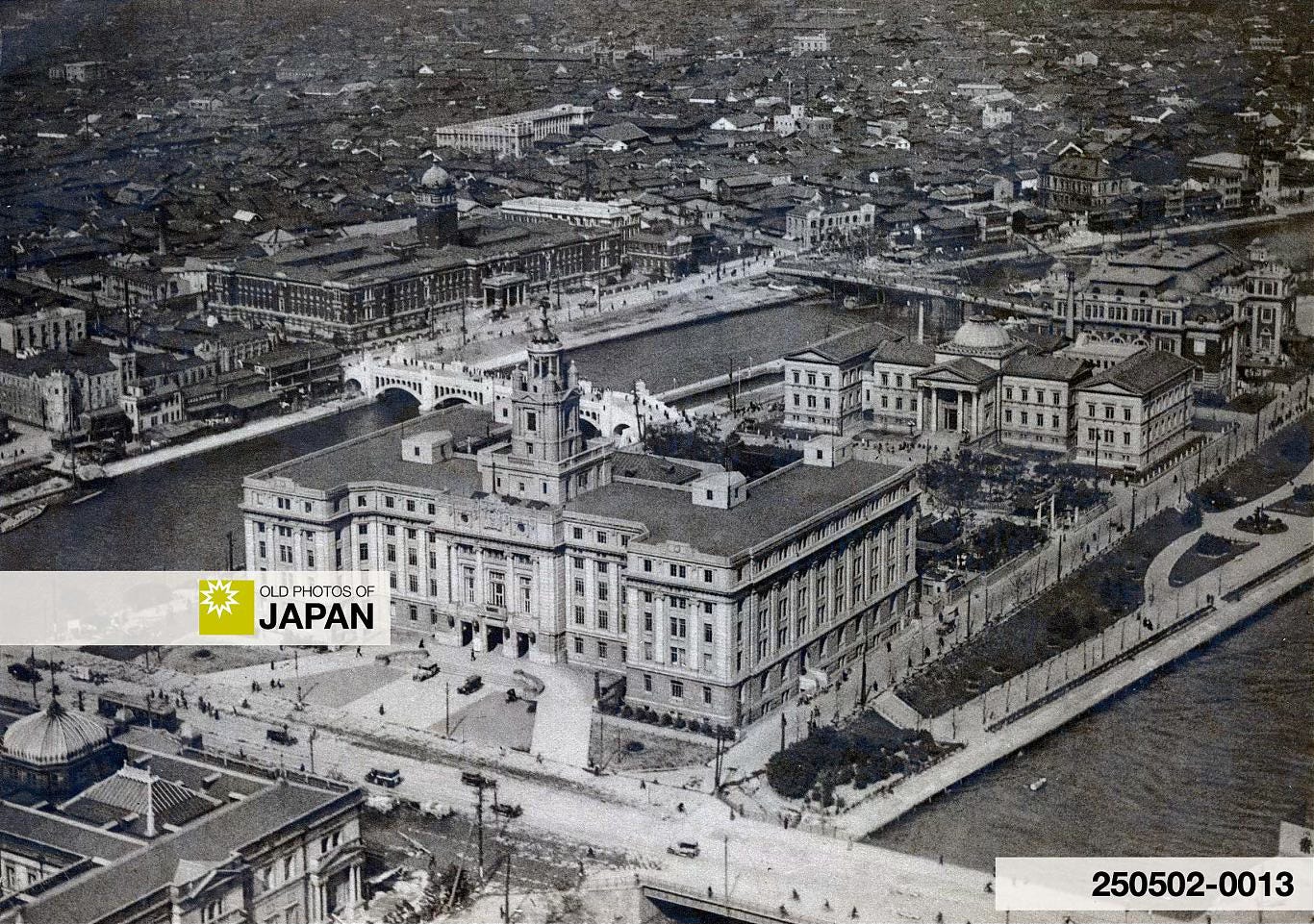

Osaka’s brand-new heart in the 1920s, the government district on Nakanoshima. The imposing building in front is Osaka City Hall, completed in 1921 (Taisho 10). From here a modern Osaka was created.

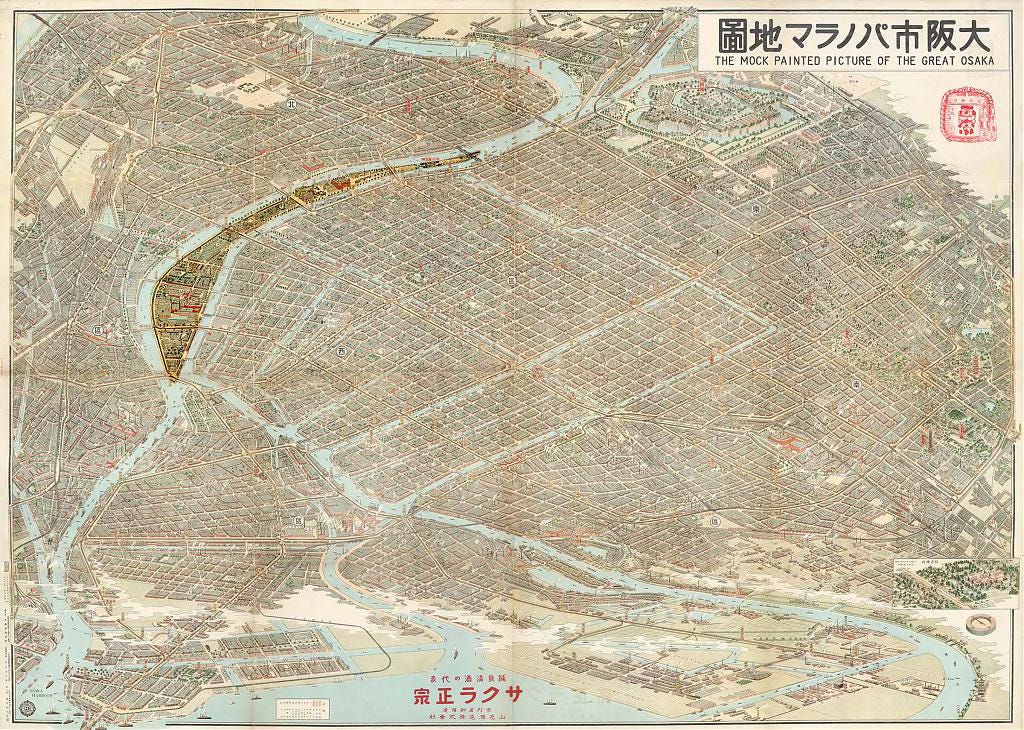

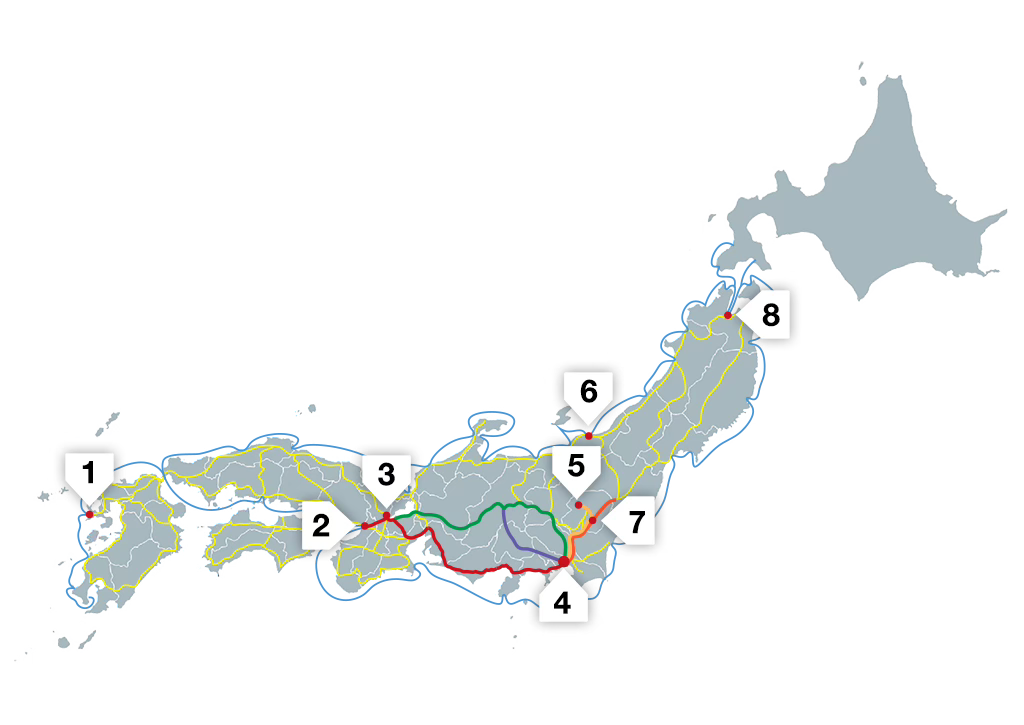

The article The Art of Looking Down briefly introduced Japan’s rich tradition of bird’s-eye view art, highlighting the early 20th-century boom of a new genre: colorful, realistic maps inspired by the rise of aviation and a domestic tourism industry. The article specifically looked at a masterpiece of this genre, the almost impossibly detailed Osaka Panorama Map, published in 1924 (Taishō 13).

In this article, we take a closer look at that map (shown below), zooming in on Nakanoshima, Osaka’s administrative and commercial heart. Pairing select sections of the map with aerial and street-level photos from the same era will reveal the creator’s brilliance as well as Osaka’s dramatic transformation.

Nakanoshima is a small island, just three kilometers long. Despite its modest size, it has played a surprisingly influential role. In the 1920s, it stood at the very center of Osaka’s push toward modernity.

To better understand this sliver of real estate in the middle of Osaka’s main river, we begin by exploring Nakanoshima during the Edo period (1603–1868).

Samurai, Merchants, Visionaries

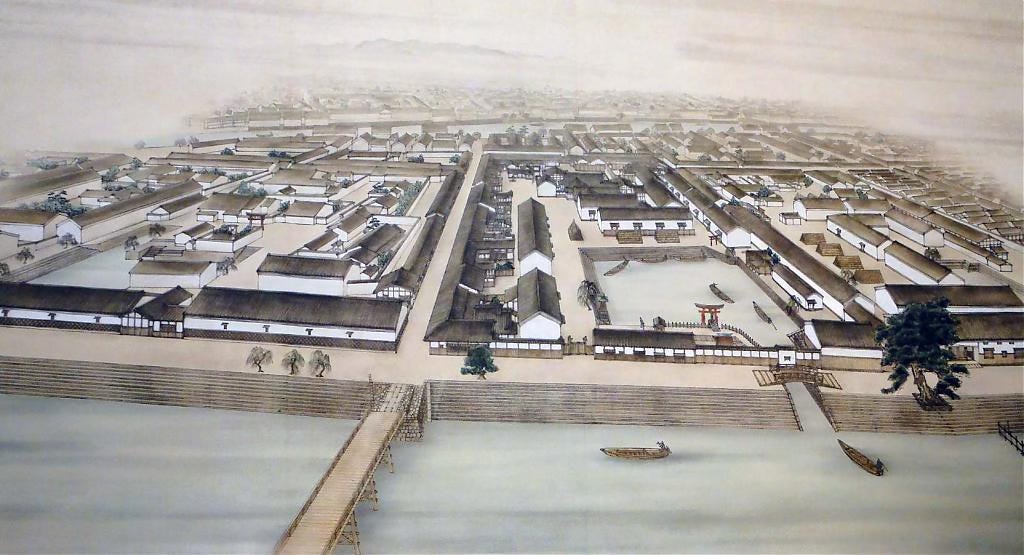

During the Edo Period, Nakanoshima and its surrounding area grew into a vital hub of commerce and logistics, its influence extending well beyond Osaka itself. It was packed with kurayashiki (蔵屋敷), storehouse-residences used by daimyō (feudal lords) to manage, store, and sell rice collected as tax, and regional specialties.1

At its peak in the early 1800s, Osaka housed more than 110 of such kurayashiki.2 The majority were on Nakanoshima and neighboring islands, including Dōjima. This is clearly visible on this 1832 (Tenpō 3) map on which kurayashiki are colored red.

Osaka was an ideal location for daimyō to establish warehouses and trading offices. A concentration of skilled artisans and early exposure to foreign technologies had made the region a manufacturing hub of high-quality goods ranging from tools and weapons to medicine, clothing, and artworks.3

This environment enabled the kurayashiki not only to sell goods but also to obtain items unavailable within the daimyō’s own domains. The commercial market resulting from this trade was crucial to the domains’ financial management.

More significantly, Osaka held an exceptionally strategic position. It stood at the eastern end of one of Japan’s busiest transportation routes, the Seto Inland Sea. It also sat at the mouth of the Yodogawa River, linking it to the imperial capital of Kyoto and Lake Biwa‘s hinterland. A coastal sea route and two roads linked it to Edo (Tokyo). Osaka was the beating heart of a vital transport network.

What made Osaka especially appealing, however, was its merchant class. With expertise in handling commodities from across the country, Osaka merchants were essential to the smooth operation of the kurayashiki system. They managed logistics, facilitated sales, and provided credit — crucial functions for supporting the domains’ economic activities.

Some core kurayashiki functions were entrusted to these local experts. Chōnin kuramoto (町人蔵元) oversaw the storage and sale of rice, and kakeya (掛屋) acted as financial agents, operating much like modern bankers.4

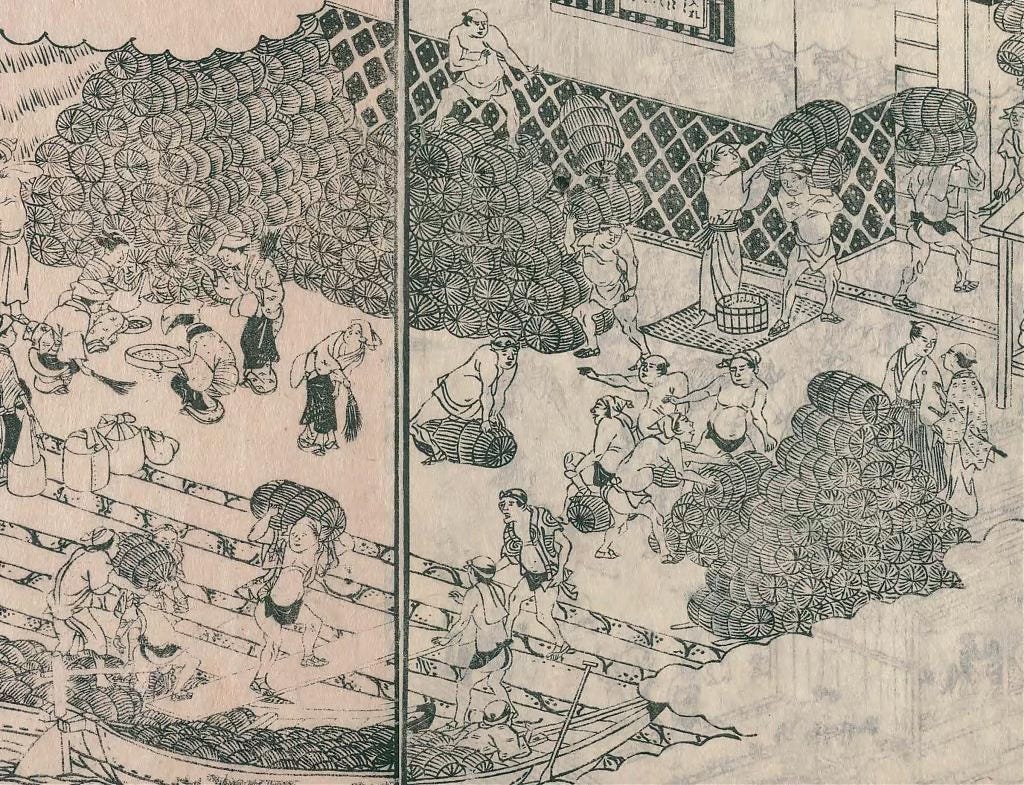

Such close interdependent relationships between domain officials and merchants naturally led to the establishment of an official rice market on Dōjima.5 There, an innovative trading system emerged, supported by credit and clearing houses.

An especially important innovation was trading in the form of rice bills (米切手, kome kitte) instead of the actual rice itself. When the maturity period of these bills was extended to 18 months, it opened the door to new forms of trading. Soon, more bills were in circulation than there was rice. By 1749 (Kan’en 2), rice bills represented nearly four times the rice actually available for delivery.6

This growing market activity gave rise to sophisticated trading mechanisms and financial innovations for hedging price risks and stabilizing the market. Dōjima merchants pioneered futures trading in the early 1700s, over a century ahead of the Chicago Board of Trade.7

The Dōjima Rice Exchange also broke new ground in market communications. It relayed daily market prices to other markets via flag signals at speeds exceeding 700 kilometers per hour. Studies suggest that a message could reach Kyoto in just four minutes, Hiroshima under 40 minutes, and Tokyo in eight hours.8 On the postcard above, signal platforms are still visible on neighboring houses.

Through all these innovations, Osaka’s Rice Exchange effectively set the benchmark rice price for the entire country.

Kurayashiki

The artists’s impression below captures the kurayashiki’s scale and complexity. Note the private harbors within the compounds. Known as funa-iri (舟入), they facilitated unloading cargo. Small canals connected them to the river.

The next photo, taken around 1870, shows part of the Nakanoshima kurayashiki of the Kurume Domain (in present-day Fukuoka Prefecture). On the right is a funa-iribashi (舟入橋), a small bridge that crossed the canal leading into the compound.

In the background, the Taminobashi Bridge (田蓑橋) can be seen. Between this bridge and the Kurume compound stood the kurayashiki of the Hiroshima Domain. Make a mental note of those two sites, the next article shows them in 1929.

This woodblock print shows the same area from the river.

After the Tokugawa Shogunate’s downfall in 1868, the new Meiji government abolished the feudal domain system and replaced it with a prefectural system in 1871 (Meiji 4). With the dissolution of the domains, the kurayashiki were torn down. Any remaining structures were destroyed in the Great Kita Fire of 1909, which especially devastated Dōjima.

The demise of the kurayashiki system dealt a heavy blow to Osaka. The city’s commercial base crumbled, and several major Osaka merchant houses went bankrupt. Yet, the city’s entrepreneurial spirit proved resilient. In 1897 (Meiji 30), construction began on a new seaport designed to accommodate large, modern ships. The first phase of this ambitious project was completed in 1929 (Shōwa 4).

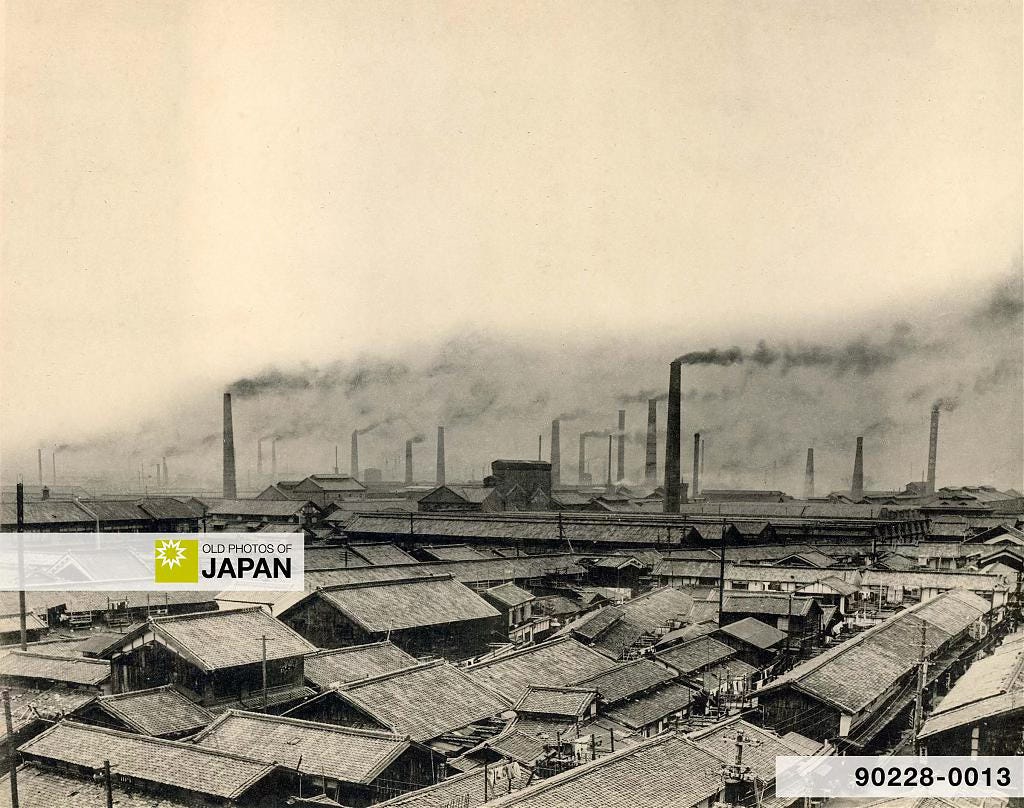

Simultaneously, Osaka reinvented itself as an industrial powerhouse. The Osaka Cotton Spinning Co. (now Toyobo) was founded in 1882 (Meiji 15), soon followed by over twenty other cotton spinning companies, and other industries.9 Osaka became known as the City of Smoke (煙の街, kemuri no machi).

Nakanoshima underwent a dramatic transformation during this period.

Into the Future

Let’s now look at how Nakanoshima had changed when the Osaka Panorama Map was published in 1924. To better showcase the details of the map, the section depicting Nakanoshima has been divided into three parts, as indicated below.

1. Central Nakanoshima

We begin with the highlighted area in the center. Because it housed many official buildings it was known as the government district (公館地區, kōkan chiku).

Four of the buildings on the map are still standing today: the Dōjima Building (1), Bank of Japan (2), Osaka Prefectural Library (6), and the Central Public Hall (7).

The photo below shows the area in 1929 (Showa 4). City Hall, the Prefectural Library, the Central Public Hall, and the Court of Appeal are all clearly visible.

Here is the same area viewed from the opposite side in 1925 (Taisho 15), the year following the map’s publication. In 1924, the Osaka Hotel was destroyed by fire, and a large empty space remains where the hotel once stood.

Let’s have a closer look at some of the buildings:

◆ Osaka City Hall

Sadly, this stately building was torn down in 1982 (Showa 57). When completed in 1921 (Taisho 10) the five-story reinforced concrete building was Osaka’s tallest.

Directly behind city hall stood Hōkoku Jinja (豊國神社), a shrine dedicated to Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), one of Japan’s three great unifiers alongside Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616). The nationalistic shrine was a popular spot for viewing cherry blossom.

In 1961 (Showa 36) it was moved to Osaka Castle. Barely visible on the far right in the above photo, it can be clearly recognized on the map (5).

◆ Central Public Hall

Osaka Central Public Hall was opened in 1918 (Taisho 7). It served as a vital hub for the growth of art and culture in Osaka. Albert Einstein and Helen Keller held lectures here, and operas and concerts by world-class artists were performed at the hall.

Its construction was made possible by a 1 million yen donation from speculator and businessman Einosuke Iwamoto (岩本栄之助, 1877–1916). Tragically, Iwamoto lost his fortune in the market and took his own life before the building was completed. He was just 39 years old.

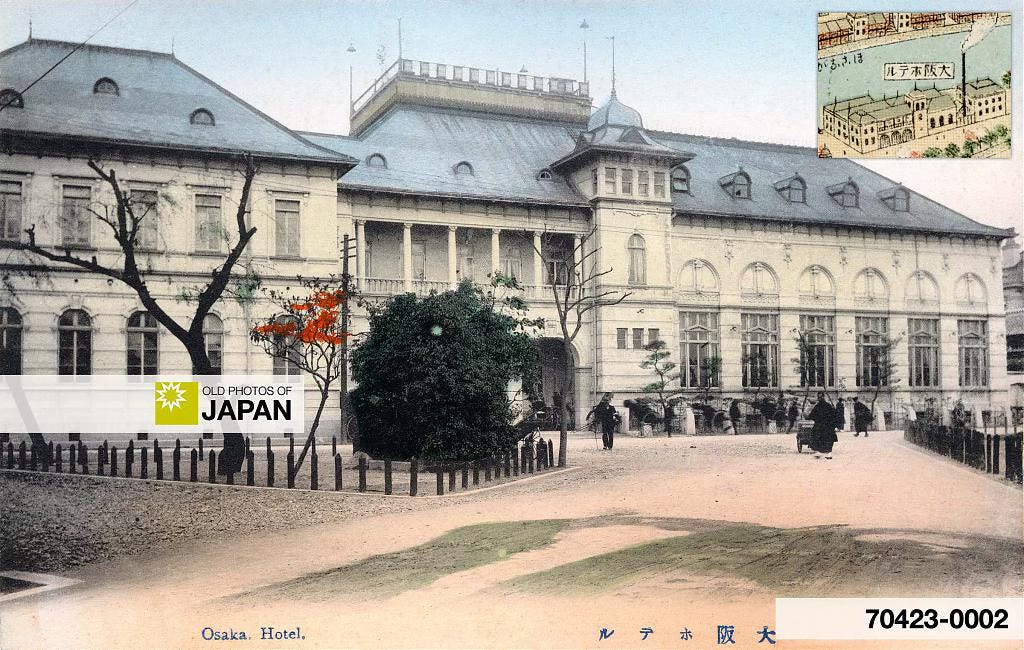

◆ Osaka Hotel

As Osaka’s premier Western hotel, the Osaka Hotel was the first with electric light, steam heating, and English speaking personnel. The 1920 edition of the reputable Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire highly recommended the hotel:10

The average traveler will find the Osaka Hotel more satisfactory, in every way, than the native inns, which are not properly equipped to cater to the requirements of foreigners. Nor is English spoken in all of them.

Terry's Guide to the Japanese Empire (1920)

The hotel was destroyed by fire in the very year that the map was published. It was never rebuilt — its time had passed. New luxury hotels offering modern comforts took its place, notably the Dōjima Hotel (1923) and the New Osaka Hotel (1935). Built nearby, they underscored Nakanoshima’s role as the heart of Osaka.

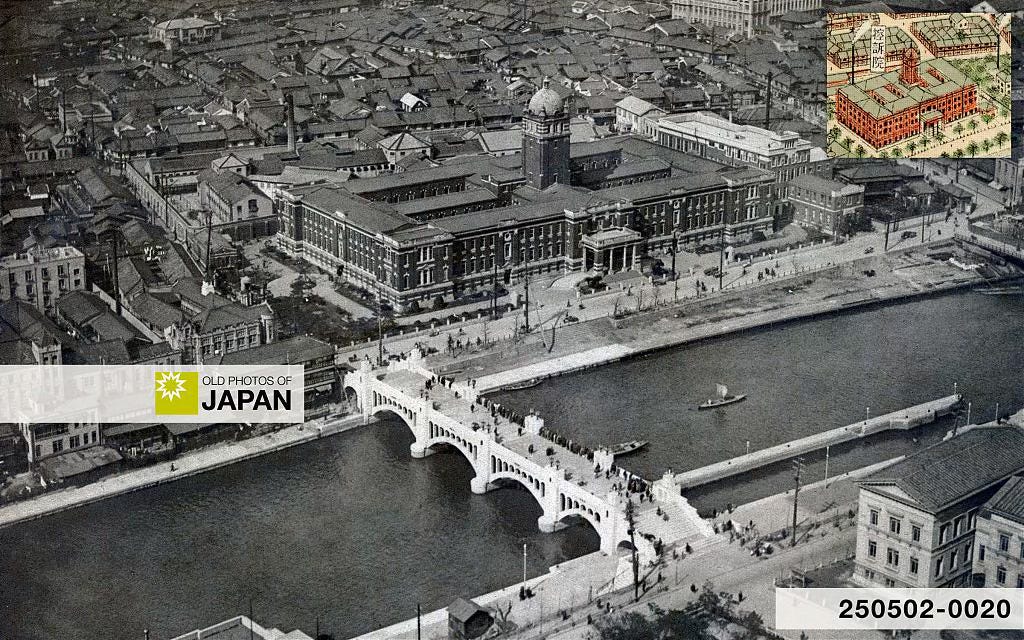

◆ Osaka Court of Appeal

The bridge in the center is Suishobashi Bridge (水晶橋), a ferro concrete bridge completed in 1929 (Showa 4) to serve as an adjustable weir. Here it is brand-new. The court building, built in 1916 (Taisho 5), was torn down in 1974 (Showa 49), but Suishobashi survives.

◆ Dōjima Building

The renowned Dōjima Building, located beside the Oebashi Bridge, was completed in 1923 (Taisho 12). It took 20 months and 128,000 craftsmen and other workers to build the then state-of-the-art ten-floor reinforced concrete building.

The building served as the headquarters of the Takenaka Corporation and was home to a range of other distinguished tenants. Among them were the popular Dōjima Hotel, favored by foreign dignitaries; a department store; an exclusive photo studio; a girls’ school; and schools for dressmaking and cooking, the latter led by the founder of the influential Tsuji Culinary Institute.

Other notable occupants included publishing house Platonsha (プラトン社), a leader in Hanshinkan modernism (阪神間モダニズム), and Seikosha (清交社), a prestigious social club established in 1923 with prominent members such as the founders of Panasonic, Hankyu Hanshin Toho, and Sharp.

With its striking ivory façade, the building stood in bold contrast to the sea of low, dark rooftops surrounding it. As a vibrant hub where politicians, entrepreneurs, intellectuals, and female students converged, it became an architectural landmark and symbol of a modernizing “Greater Osaka.”

The building still stands today, but two major renovations — in 1960 (Shōwa 35) and 1999 (Heisei 11) — have significantly altered its appearance.11

◆ Dōjimagawa River

The next photo shows the Dōjimagawa River in 1913 (Taisho 2). Nakanoshima is on the right. The Oebashi Bridge can be seen in the center, the Court of Appeal in the back. The Dōjima Building has not yet been built.

For a current bird’s-eye view of central Nakanoshima from roughly the same angle as shown on the Osaka Panorama Map, click the link to Google Maps:

We will continue with the western and eastern sections of Nakanoshima in the next article. Stay tuned!

Continue to Nakanoshima: Modern and Vibrant.

Notes

Such as bonito flakes from the Tosa Domain, tatami mats from the Fukuyama Domain, and indigo balls from the Tokushima Domain. 各時代の中之島 江戸期の中之島 – 物流・金融・情報で、創意工夫が息づく中之島, 一般社団法人 中之島まちみらい協議会. Retrieved on 2025-04-18.

Information provided by The Osaka Museum of Housing and Living. Some sources claim there were as many as 124 kurayashiki. For example: 須々木庄平 (1940).『堂島米市場史』東京:日本評論社, 6 (republished in 2018).

Yukichi Fukuzawa (福澤 諭吉, 1835–1901), founder of Keio University and the newspaper Jiji-Shinpō, was born at the kurayashiki of the Nakatsu Domain (中津藩, present-day Ōita, Kyushu), located on Dōjima.

Miyamoto, Matao (1999). The Development of Commerce in the Edo Period. Journal of Japanese Trade and Industry, May/June 1999, 38. Retrieved on 2025-05-01.

Schaede, Ulrike (1989). Forwards and Futures in Tokugawa-period Japan: A New Perspective on the Dojima Rice Market. Journal of Banking & Finance, 1989, vol. 13, issue 4-5, 491.

ibid. “In 1730, the authorities officially acknowledged the market place as an exchange. It was at the same site that a modern commodities exchange was established in 1871.”

ibid, 492–493.

ibid, 496. “The development and formalization of trading practices was not a government-led process but emanated from the market’s own dynamics. The exchange was an autonomous, voluntary, non-profit association of its members, and its main function was supervising everyday trading, so it regulated brokers and auctions, settled disputes, registered official daily closing prices, and collected fees for its operations.”

There are a number of studies suggesting that futures trading was pioneered earlier in other countries, especially in the Netherlands. For example:

Jonker, Joost; Gelderblom, Oscar (2005). Amsterdam as the Cradle of Modern Futures Trading and Options Trading, 1550-1650 in The Origins of Value. The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 189-206.

Mount Hatafuri (旗振山, Flag-waving Mountain) in Kobe reminds of this system. Sources used:

柴田昭彦 (2006).『旗振り山』ナカニシヤ出版.

柴田昭彦 (2021)『旗振り山と航空灯台』 ナカニシヤ出版.

Toyoda, Takeshi (1969). A history of Pre-Meiji Commerce in Japan. Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, 66.

Takatsuki, Yasuo (2022). The Dojima Rice Exchange: From Rice Trading to Index Futures Trading in Edo-Period Japan. Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture (JPIC).

Abe, Haruki (2024). Ahead of the Times: Flag-Waving Communication and Japan’s Dōjima Rice Exchange. Nippon Communications Foundation. Retrieved on 2025-05-01.

The Sojitz History Museum. Driving the Development of Japan’s Cotton Spinning Industry as a Direct Importer of Cotton. Retrieved on 2025-05-05.

Terry, T. Philip (1920). Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 607.

「大大阪」から「令和」まで。100年の歴史を刻み、未来を創造するためのビル, 堂島ビルヂング. Retrieved on 2025-04-23.

I'm especially interested in .... (of course) the cotton spinning and other cotton manufacturing that developed in Osaka.

Great maps! Looking forward to seeing some of this!

So often people seem to ignore the development of industrialisation outside of Europe and America. It’s really interesting to see western influence get developed by other countries, and also how they did so much without influence at all. There is such complexity and nuance that people often ignore, but you are getting it right every time it seems!