The Art of Looking Down

A rare illustrated bird’s-eye view map of Osaka from 1924 offers profound insights

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

After Japan’s first powered airplane flight in 1910, the country saw a boom in stunning bird’s-eye view maps. This essay explores a masterpiece of this genre, a 1924 map of Osaka.

Japan has a long and rich tradition of bird’s-eye view art.1 As early as the Heian period (794–1185), illustrated emaki scrolls of The Tale of Genji (源氏物語, Genji Monogatari) employed elevated perspectives to depict indoor scenes and architectural layouts.

Between the 1500s and 1700s, elaborate byōbu folding screens portrayed Kyoto from high above, capturing the city in dazzling detail. These works are known as rakuchū rakugai-zu (洛中洛外図), or “scenes in and around the capital.”

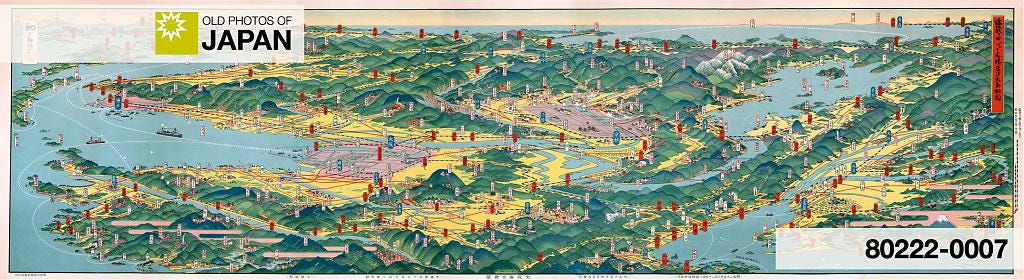

During the Edo period (1603–1868), bird’s-eye perspectives continued to flourish, particularly in woodblock prints. One of the most ambitious examples is Tōkaidō Meisho Ichiran (東海道名所一覧, The Famous Places of the Tōkaidō Road in One View), created in 1818 (Bunsei 1) by Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎, 1760–1849). It presents the famed coastal route in a sweeping, unified panorama.

The rise of aviation and a booming domestic tourism industry in the early 20th century gave birth to a new genre of bird’s-eye view art: colorful modern maps, grounded in realism.

Among the pioneers was Hatsusaburō Yoshida (吉田 初三郎, 1884–1955), a prolific cartographer and artist. He painted his first bird’s-eye view map — a guide for the Keihan Electric Railway — in 1914 (Taishō 3). By the time of his death in 1955 (Shōwa 30), he had produced over 2,000 such maps.

Osaka Panorama Map

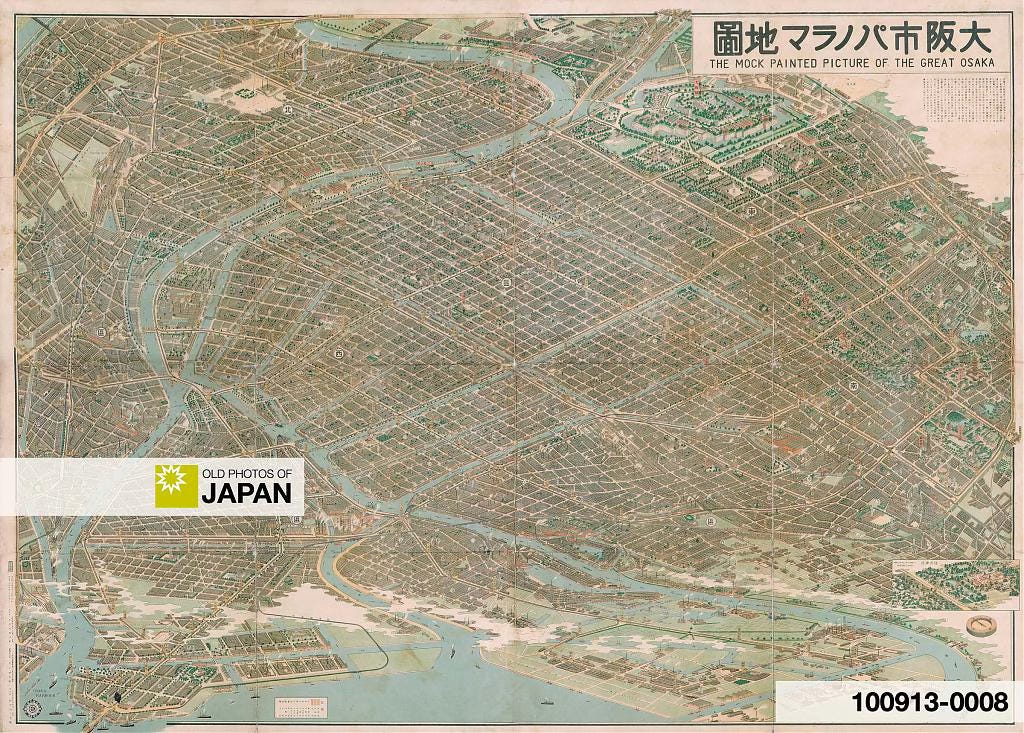

Amid this cartographic explosion, one particular work stands out: a 1924 (Taishō 13) bird’s-eye map of Osaka, drawn by an otherwise obscure artist. Exceptional in both execution and historical value, the map captures the city in the throes of modernization, industrialization, and explosive growth.

It preserves Osaka at a pivotal moment, precariously straddling past and future. Streetcars — launched in 1903 (Meiji 36) — signal progress, yet water transport and narrow roads still linger. Western-style buildings stand next to traditional townhouses, while factory chimneys loom along the city’s fringes.

Four months before the map’s publication, Tokyo and Yokohama were devastated by the Great Kantō Earthquake, forcing the industrial city of Osaka and the nearby port city of Kobe to take over the two cities’ main economic functions, while taking in large numbers of displaced people.

Just one year after this map was published, Osaka absorbed 44 surrounding towns and villages and named itself Greater Osaka (大大阪, Dai Osaka). With a population of 2.1 million, up from just 272,000 in 1873 (Meiji 6), it had become Japan’s most populous city. As a leading commercial hub in Asia, it stood on the global stage.2

These monumental transformations took place under the leadership of Osaka’s visionary mayor, Hajime Seki (關 一, 1873–1935). As Osaka’s mayor from 1923 through 1935 (Showa 10), Seki was instrumental in the construction of ports, railways, public markets, a subway system, and city-provided housing. His groundbreaking thirty-year urban development plan aimed to make the “city of smoke” livable again and is still a textbook case for urban planners today.3

Seki is especially famous for the construction of Midōsuji Avenue, the wide main street that connects Umeda in the city’s north with Namba in the south. On this map it does not yet exist.

This invaluable map is surprisingly rare. In the United States, it is held only by UC Berkeley and the University of Chicago. Even in Japan only five libraries list it in their collection. The Duits Collection is extremely fortunate to have two original editions: the standard version (shown above), and a promotional variant. Each measures an impressive 79 by 109 centimeters (31 by 43 inches).

The map’s introduction — printed in the top-right corner — notes the immense effort that was required to accurately capture Osaka’s essence and describes the map as “a modern and unprecedentedly important reference.”

Each significant building is named or specially marked, clearly distinguishing it and making it easy for anyone to recognize at a glance. … Even the old city center and the new urban areas (such as the eastern port area), as well as the city’s outskirts and narrow alleyways, have been portrayed with minimal omissions or errors. Therefore, it is to be hoped that viewers will appreciate this as a precise and nearly complete representation of Osaka as it currently stands.

Warajiya, Osakashi Panorama Chizu (1924)

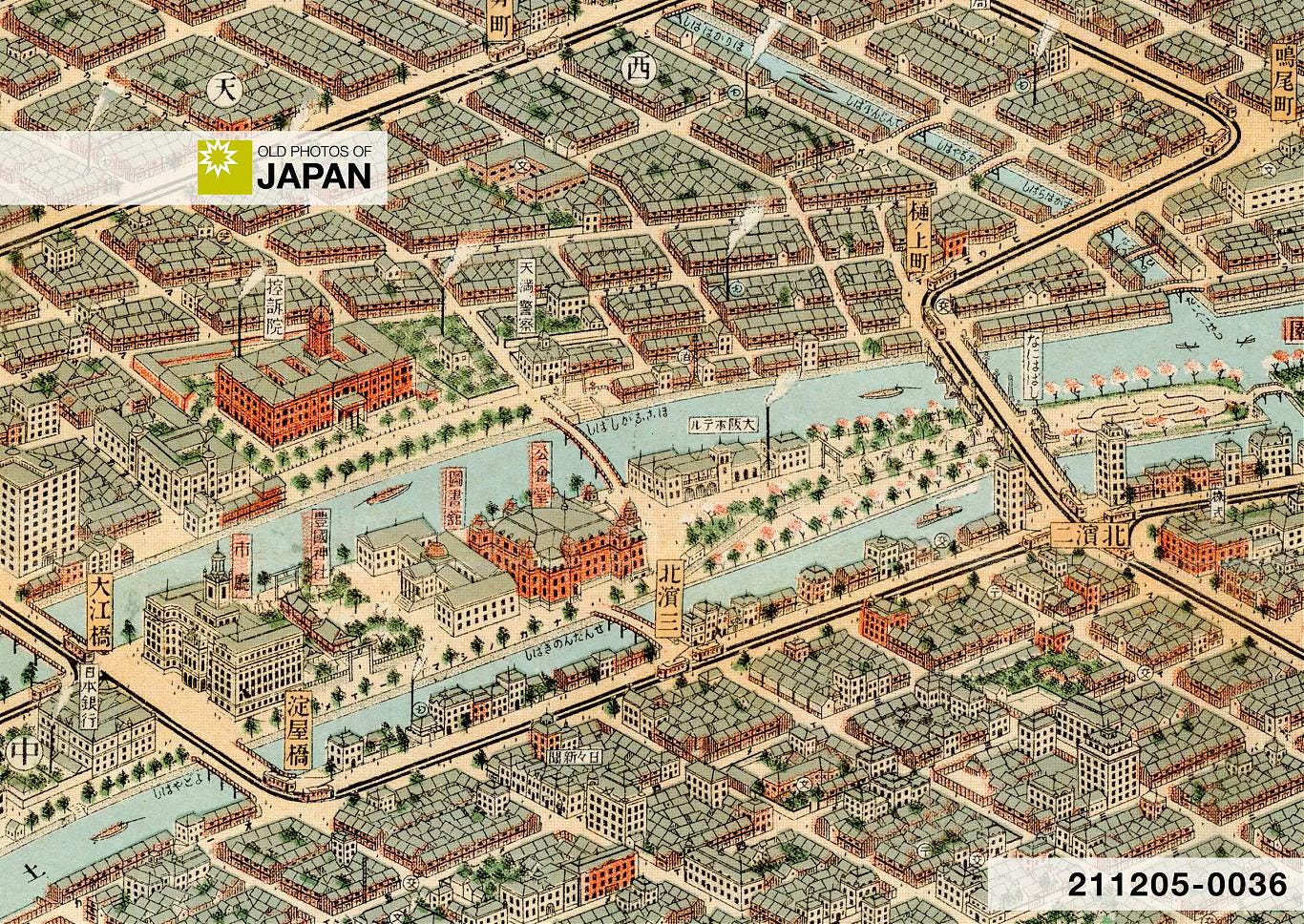

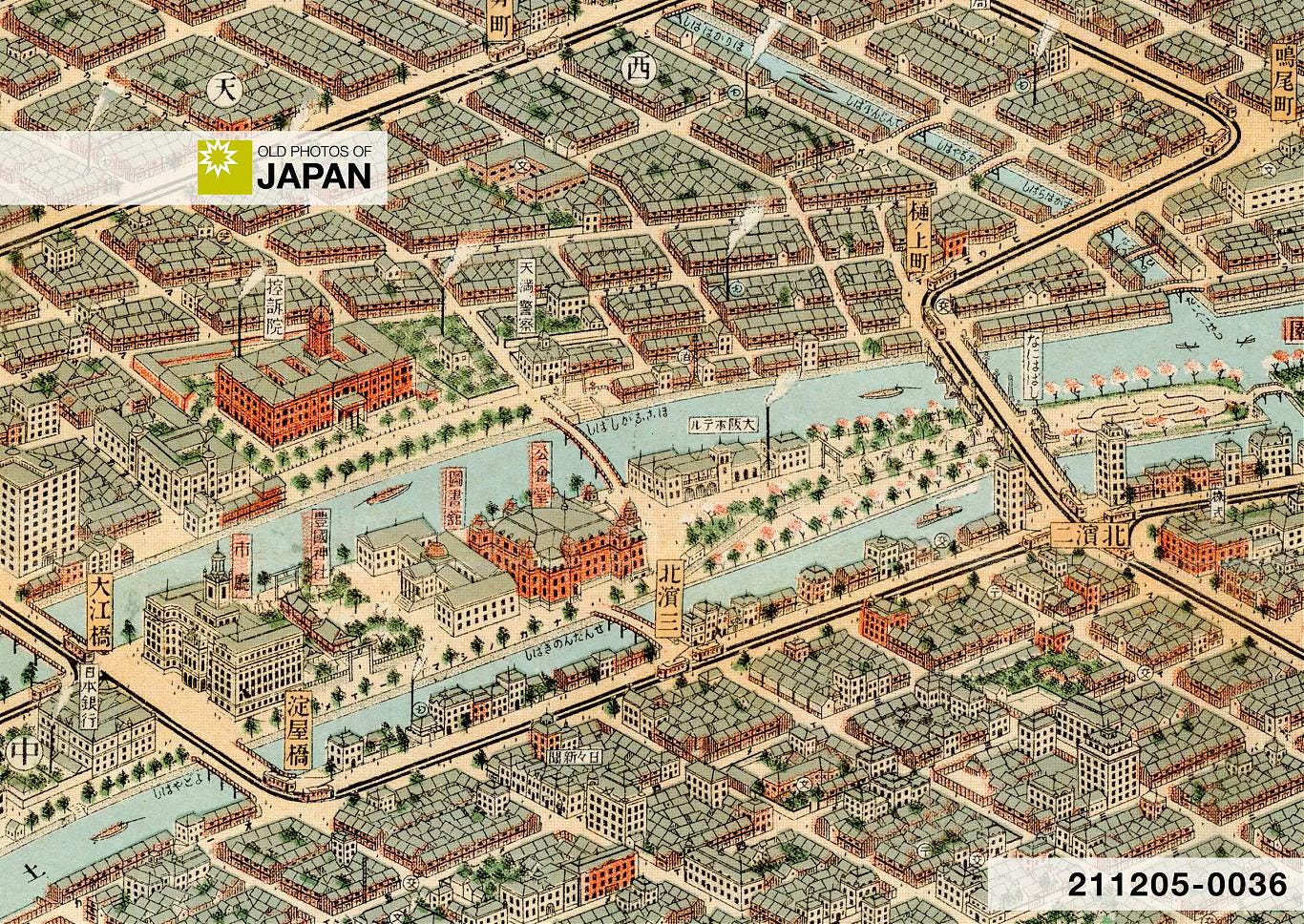

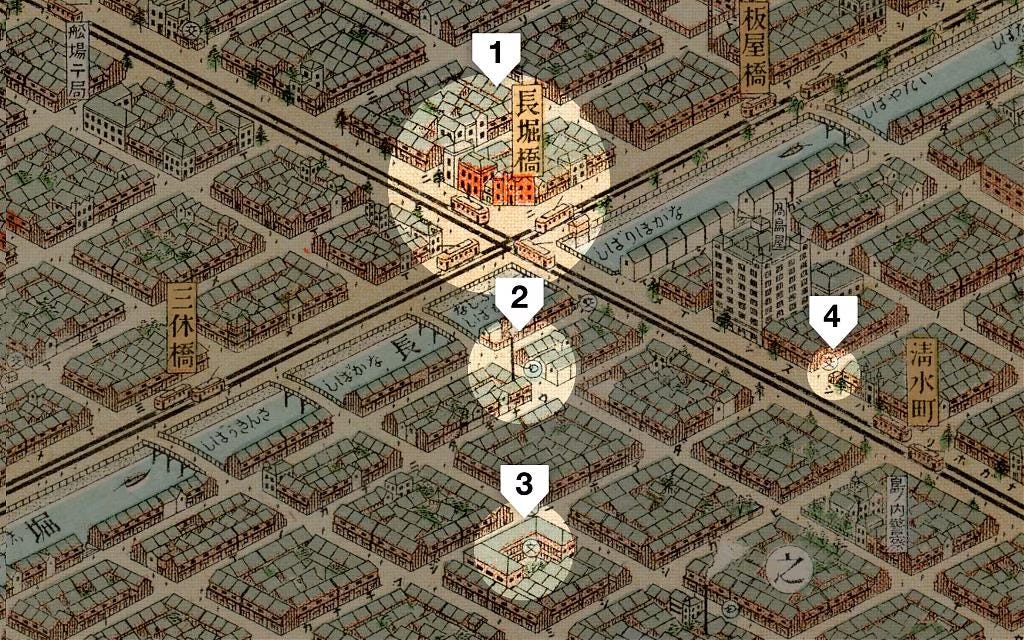

The map is incredibly detailed, marking public facilities like schools, post offices, neighborhood police stations (kōban), and bathhouses (sentō), as well as temples, shrines, department stores, and even individual streetcar stops, cleverly illustrated with a streetcar for each stop. The precision is striking – at intersections there are four streetcars, each indicating a stop for a different direction.

The postcard below shows what the intersection highlighted on the map looked like in real life. Some buildings in the photo can be easily recognized on the map. The wide avenue is Sakaisuji, then Osaka’s main street with a busy streetcar line and four department stores. The photographer stood on the roof of one of them.

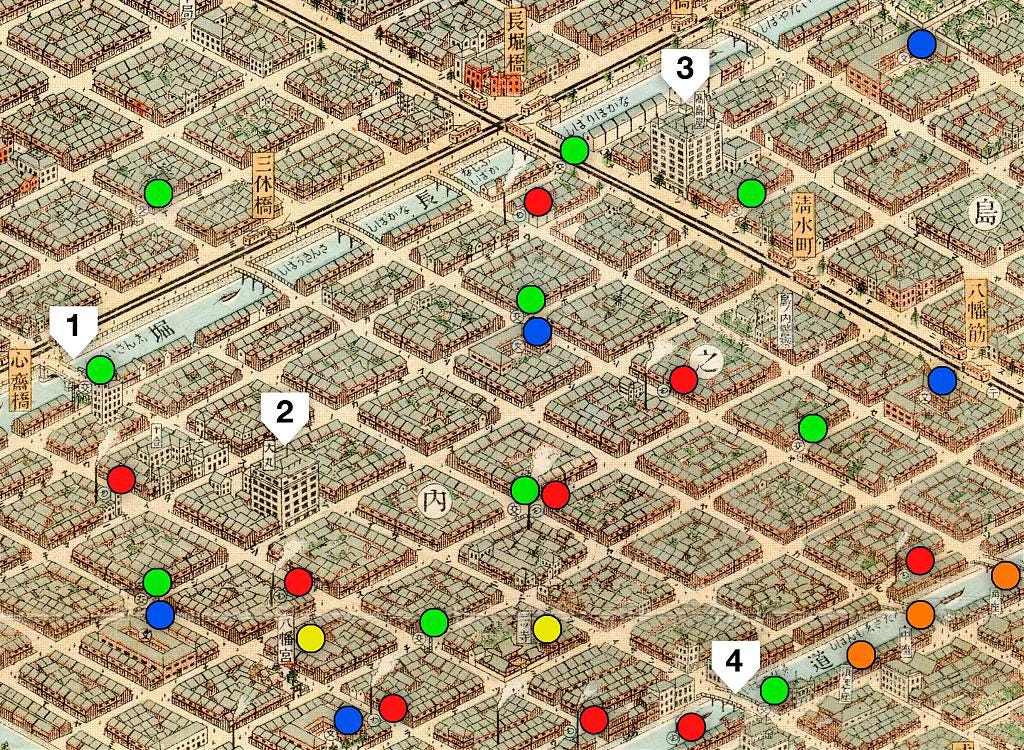

The map’s ingenious design offers valuable insight, as illustrated in the close-up below of the Shinsaibashi shopping district. To enhance clarity, I have added color-coded circles. Note the surprisingly large number of kōban (green), sentō (red), and schools (blue). This reveals a dense urban fabric.

For years, I wondered how I could convey the map’s artistry and significance. That question was unexpectedly answered when I recently acquired aerial photos of Osaka from the same era. Many of the photographed buildings are illustrated on the map, underscoring the creator’s meticulous attention to detail.

I already had street-level photos from this period. Juxtaposing these two sets of images with sections of the map reveals not only its technical craftsmanship, but also Osaka’s dramatic transformation during this era.

This is especially apparent on and around Nakanoshima, the city’s administrative and commercial heart. The next article will explore this section of the map by pairing it up with stunning vintage aerial and street-level photos.

Coming Soon: Nakanoshima: Small Island, Big Dreams.

Notes

Bird’s-eye view maps are known as chokanzu (鳥瞰図) in Japanese.

Recommended reading: Rodgers, Ken (2021-02-27), The Big Picture: Birds’-eye Overviews of the Japanese Archipelago, Kyoto Journal.

日本地誌提要 第1冊. 日報社 (1875).

When Osaka City was officially established as a municipality in 1889 (Meiji 22), it measured a mere 15 square kilometers (6 sq mi), one-fourteenth of its current size. Some 40 square kilometers (15 sq mi) were added in 1897 (Meiji 30), but the 1925 enlargement added a whopping 126 square kilometers (49 sq mi). 近代・現代の大阪, 大阪市立図書館. Retrieved on 2025-04-18.

In 1932 (Showa 7), Tokyo became Japan’s largest city by population.

Perez, Joan; Araldi, Alessandro; Fusco, Giovanni; Fuse, Takashi (2019). The Character of Urban Japan: Overview of Osaka-Kobe’s Cityscapes. Urban Science. 3. 105. pp. 6.

Unfortunately, many of Seki’s ambitious plans to make Osaka livable failed as he lost his battles with greedy property developers. I highly recommend reading The City as Subject: Seki Hajime and the Reinvention of Modern Osaka by Jeffrey E. Hanes, published in 2002 by University of California Press.

This is exciting :-) That section of Nakanoshima looks surprisingly similar to present day. I think a lot of those buildings still exist ... and maybe even the form of the rose garden?

Absolutely fascinating to have a peek at these beautiful maps!

Fascinating read! I was always impressed by the bird’s eye view paintings whenever I saw them in muesuems and galleries, so it’s great to learn more about them!