Osaka 1929 • City Of Smoke

In the 1920s, Osaka Castle was a weapons factory, and had no tower…

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

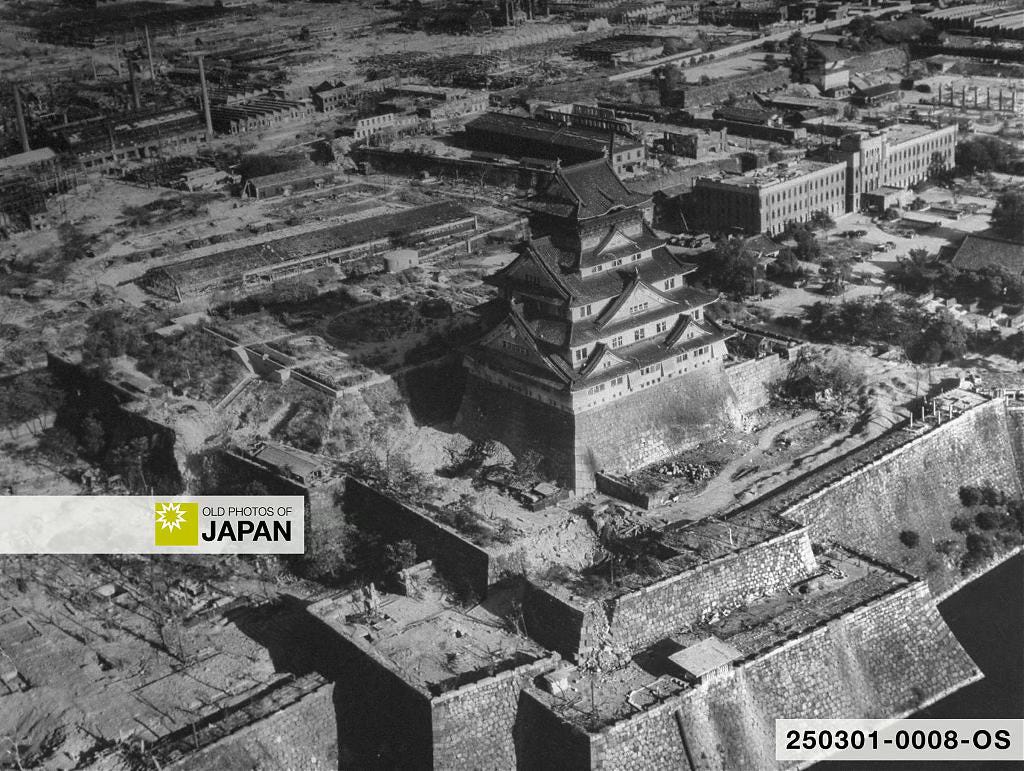

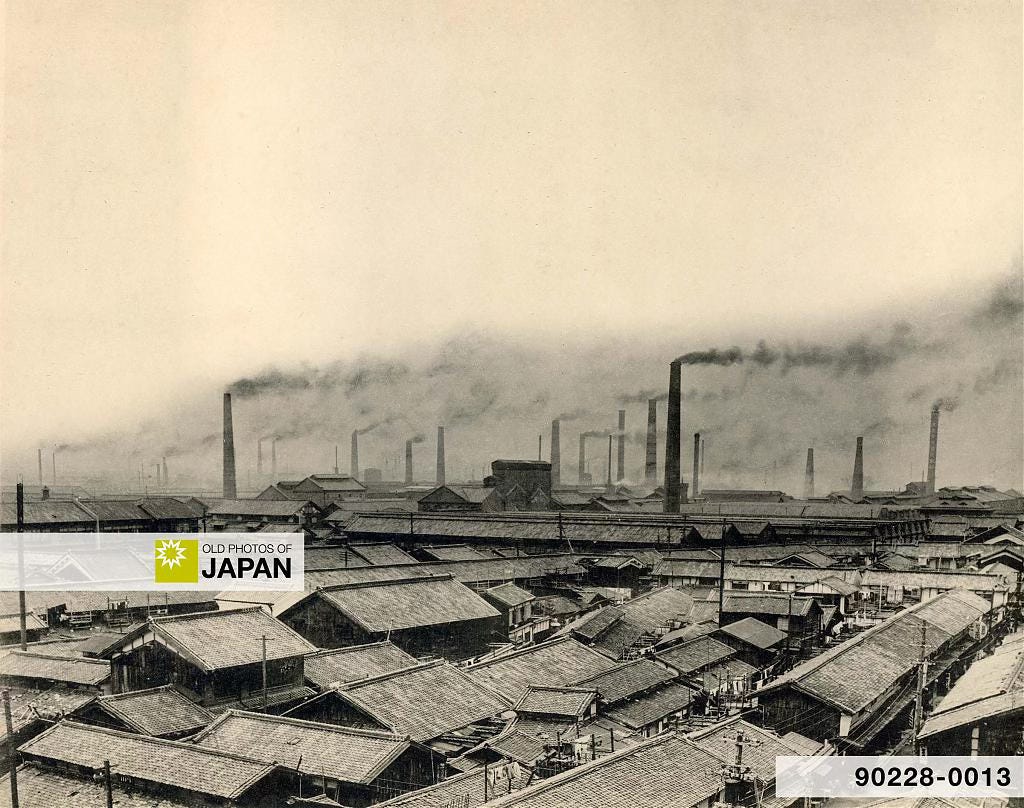

Osaka Castle in 1929. There is no main castle tower, and the castle is surrounded by factories instead of trees. At this time, Osaka was a city of smoke.

Introduction

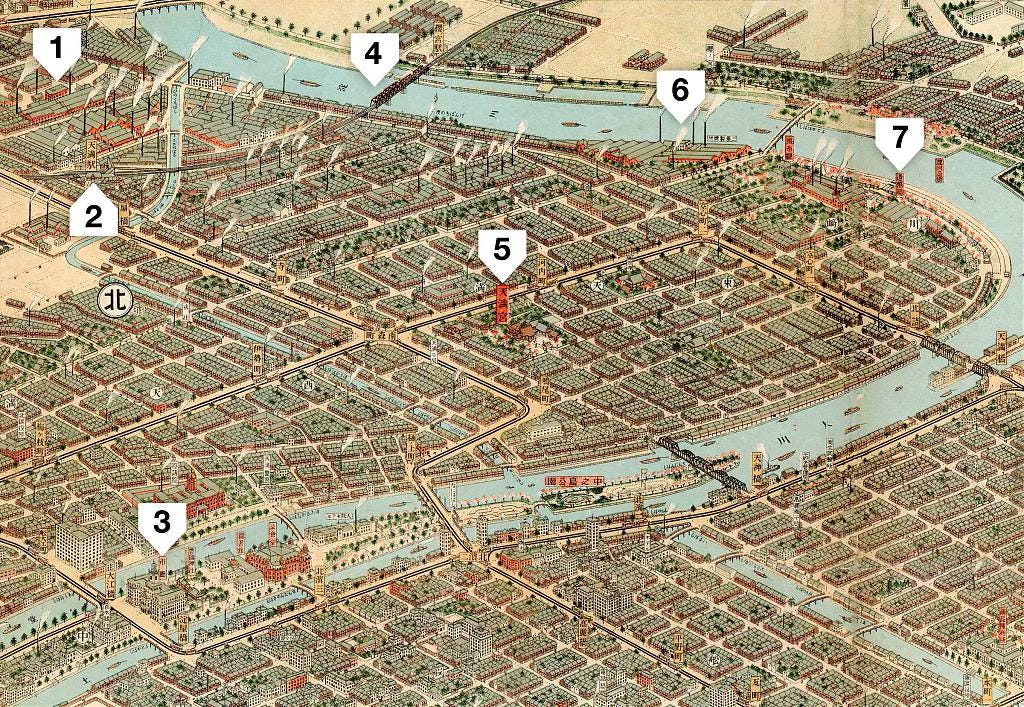

In The Art of Looking Down I briefly introduced Japan’s rich tradition of bird’s-eye view art, highlighting the early 20th-century boom of a new genre: colorful, realistic maps inspired by the rise of aviation and a domestic tourism industry. The article specifically looked at a masterpiece of this genre, the almost impossibly detailed Osaka Panorama Map, published in 1924 (Taishō 13).

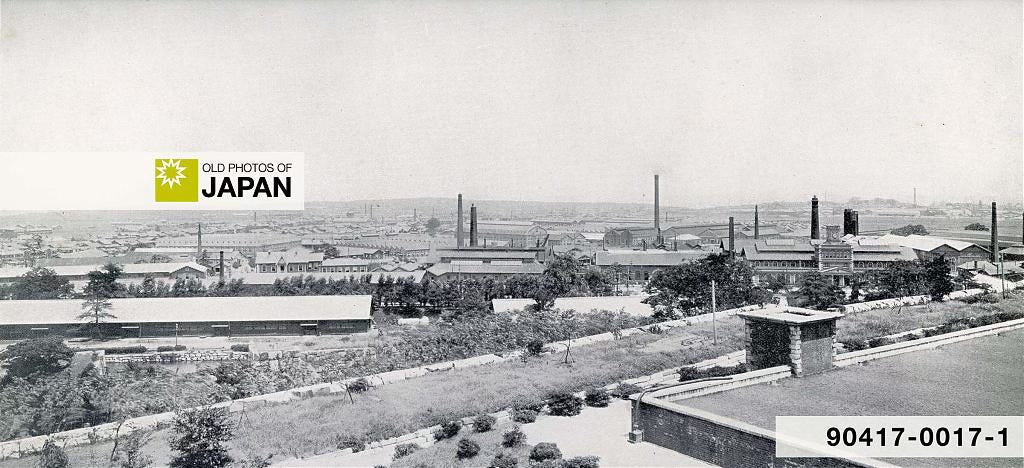

In this article, we take a closer look at that map (shown below), zooming in on Osaka Castle and one other area in Osaka where smokestacks dominated the skyline. Aerial and street-level photos from the same era reveal Osaka’s dramatic transformation into a city of smoke.

Let’s first have a look at what Osaka Castle looks like today. I shot the aerial photo below in 2006. Since then, relatively little has changed as you can see in this 3D view on Google Maps (3D may not work on mobile phones).

My photo is taken from a similar angle as the one from 1929, highlighting the dramatic transformation of Osaka Castle and its surroundings.

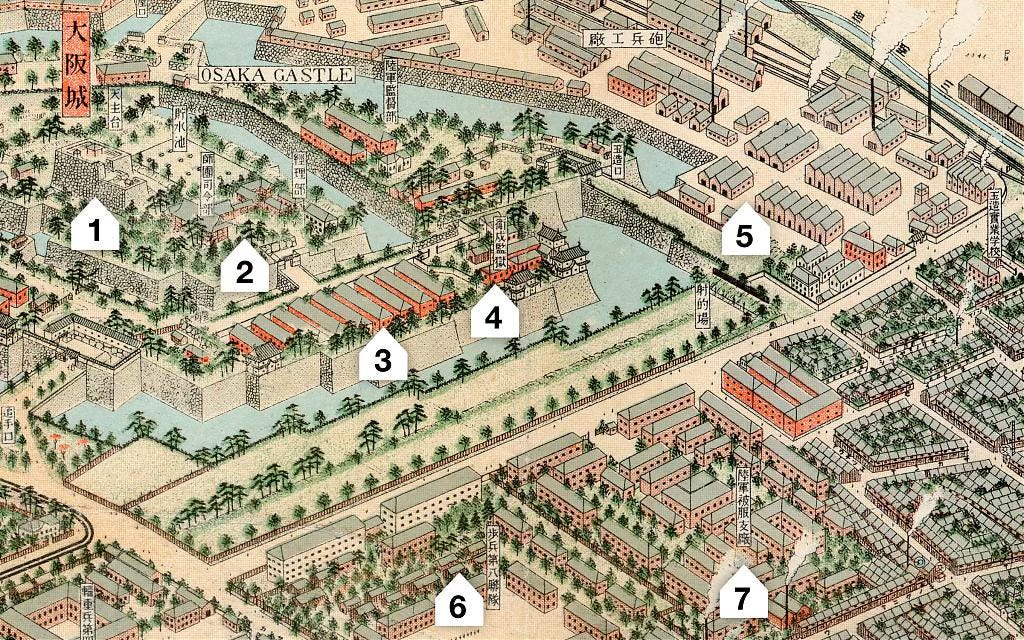

Here is the same area on the 1924 map:

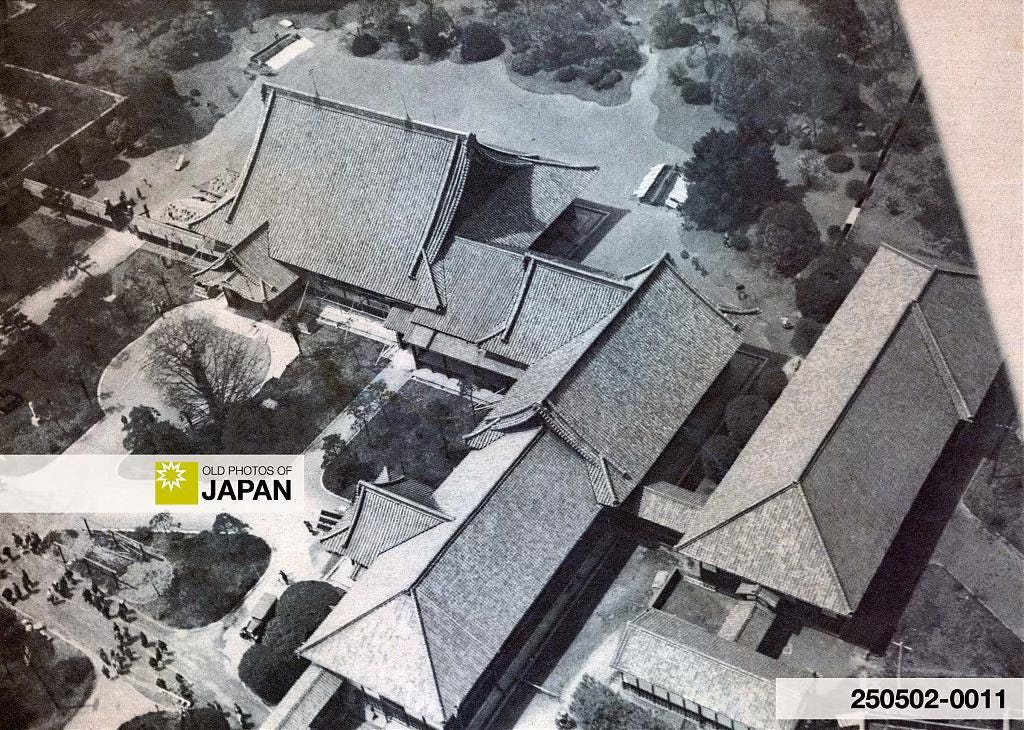

Note that there is no main castle tower (tenshu) in the images from the 1920s. It burned down in 1665 (Kanbun 5) and was only rebuilt in 1931 (Showa 6), using ferroconcrete. On the photo and the map, the spot (number 1) is still empty.

The tower is not the only building missing in the 1920s. Except for the turrets, there is only one traditional building visible on the castle grounds: Kishu Goten (紀州御殿, number 2).

This building was actually originally part of Wakayama Castle. In 1885 (Meiji 18) it was dismantled and rebuilt on the grounds of Osaka Castle. Here it was used as the headquarters of the Osaka Garrison (大阪鎮台). It burned down in 1947 (Showa 22) while in the possession of US armed forces.

By the time the Osaka Panorama Map was published, newspapers in the United States and Europe already referred to Osaka as the “Manchester of the East.” Like the British city, Osaka had become an industrial juggernaut crowned with chimneys. The city was home to a vast array of factories producing everything from textiles to ships.

One of these industries was the Osaka Arsenal, the sprawling weapons factory of the Imperial Japanese Army.1 Established at Osaka Castle in 1870 (Meiji 3), the arsenal was at the forefront of modern Japanese industry. After installing Japan’s first open-hearth furnace, it started mass production of steel in 1890 (Meiji 23).2 Subsequently, it developed most of the country’s new steelmaking techniques.

By the 1920s, it had grown to a significant size, as evident in the 1929 aerial photo of Osaka Castle and the 1924 map shown above.3 The weapons factory underwent an even greater expansion in the run-up to World War II. It was considered to be Asia’s largest weapons production site with the number of employees eventually exceeding 60,000.4

On August 14, 1945 — the day before Japan’s surrender — an American air raid destroyed 90% of the arsenal, killing over 300 factory workers. The celebrated Japanese author and peace activist Makoto Oda (小田 実, 1932–2007) was twelve when the bombers flattened the arsenal and turned Osaka into a hellscape. He once told me how angry he was about that last-minute bombing:

After the fires, I came out of the shelter and found pamphlets everywhere that had been dropped from American planes. ‘The war is over,’ they said. I was dumbfounded. If the war was over, then why the bombs? What had all those people died for?

Makoto Oda

The arsenal was never rebuilt. Today, the site houses Osaka Castle Park, the multi-purpose arena Osaka-Jō Hall, and office towers. The area that once housed the deadly weapons factory is now a bustling entertainment and business hub.

Forests of Chimneys

Osaka’s massive industrialization gave birth to a skyline dominated by smokestacks belching thick black smoke. In his 1929 book Osaka Sketches, author Glenn Shaw described the city as being shrouded in an almost perpetual “cloud of smoke.”5

Osaka lies under a cloud of smoke. When the wind blows from the east, it carries the cloud to sea and brings out the mountains inland. But it usually blows from the west and smothers them out of sight. It smothers nearly everything, so that at any considerable distance, forms cannot be surely distinguished.

Osaka Sketches, 1929

Residents essentially lived under a blanket of soot. Shaw wrote that some 18,390 US tons of the gritty, oily substance fell back on the city annually.6

Remarkably, the people of Osaka took great pride in the city’s reputation as the Capital of Smoke (煙の都, Kemuri no Miyako). This sentiment is reflected in a photo caption from a 1913 photo album published by Osaka Prefecture:7

There are countless factories in Osaka City and its surrounding areas. As a result, thick black smoke billows into the sky from the many chimneys throughout the city, creating the magnificent view captured in these photographs. This has earned the city the nickname “Capital of Smoke.”

Osakafu Shashincho, 1913

The next section of the Osaka Panorama Map shows the industrial area in the previous two photos. At the time, this area was still on the outskirts of Osaka, which made it popular for factories. I have not yet been able to locate the buildings where the photographers stood.

Many of Osaka’s smokestacks belonged to the city’s thriving textile industry, particularly its cotton spinning mills. By 1927 (Showa 2), the city was home to 24 spinning mills employing 24,200 workers, roughly 12% of the city’s workforce. They generated an astonishing 80% of the city’s industrial output by value.8

Osaka’s industrialization began with the establishment of the Osaka Arsenal in 1870 and the Japan Mint a year later. The textile industry was however the true driving force behind Osaka’s remarkable transformation into Japan’s industrial powerhouse.

Japan’s first cotton mill was founded in Kagoshima in 1867 (Keiō 3). Over the following years, numerous mills were launched across Japan, many funded by the new Meiji Government. Their operators gradually mastered the technical skills needed to rival the high-quality yarn hand-spun by women on small farms.9

However, Japanese mills struggled to compete with imported textiles. The turning point came in 1883 (Meiji 16) when Ōsaka Bōseki started operating Japan’s largest cotton mill in Osaka’s Sangenya district.10 It was equipped with 10,500 spindles, nearly five times more than the next largest mill.11

Ōsaka Bōseki holds a special place in Japan’s economic history. Founded by a key figure of the Meiji era, the company helped Japan transform into a major cotton exporter and a modern industrial power, with Osaka as its economic heart. The factory’s significant impact is commemorated by a stone monument on its former site, bearing the words: Birthplace of the Modern Spinning Industry. Arguably, it is the cradle of Japan’s modern industry as a whole.

We explore this fascinating chapter of Osaka’s industrial rise in Japan's Cotton Revolution.

Notes

The name of the Osaka Arsenal was changed frequently over its 75 year history. These days, the term Ōsaka Hōhei Kōshō (大阪砲兵工廠) is used most commonly.

Tsukamoto, Takeshi (1996). A History of Japanese Industry (4): Japan’s Industrial Revolution (1890-1913). Journal of Japanese Trade & Industry: No. 6, 45.

The description of the map relies on the map’s labels and the following paper: Kawamichi, Rintaro; Hashitera, Tomoko; Moussas, Geoffrey (2003). Military and Civil Uses of Osaka Castle in the Modern Age. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering vol.2 no.1 May 2003/205, 199–205.

Osaka Army Arsenal (Osaka Hohei Kosho), National Diet Library Japan. Retrieved on 2025-04-16.

Glenn Shaw (1929). Osaka sketches. Tokyo: The Hokuseido Press, 240.

ibid, x.

『大阪府寫真帖』, Osaka Prefecture (1913), 29.

「大阪市の煙筒と煤煙・THE CHIMNEYS AND SMOKE OF INDUSTRIAL OSAKA・大阪市及び其の附近には無数の工場相連り。 爲めに市は煙筒林立、黒煙濃濃として天に歌り、 圖に示すか如き壯觀を呈し、煙の都の名を附せらる、に至れり。」

『大阪市産業大觀』Osaka City (1929), 23.

「紡織 其一・紡績業ハ大阪市工業中ノ大宗ニシテ、昭和二年末ニハ工場數二十四、之ニ從事スル職工數二萬四千二百人、同年中ノ生產額八千七百萬圓二上り全市總工產品中職工數ニ於テ一割二分、生産額ニ於テ八分ヲ占ム。是等工場ノ運轉スル錘數ハ一日平均六十五萬使用寶馬力數ハ一日平均十一萬餘ヲ算シ、以テ本市斯業ノ盛大ナルヲ示セリ。寫眞ハ東洋紡績株式會社三軒家工場内ノ一部ヲ示ス。」

Tamagawa, Kanji. The Role of Cotton Spinning Books in the Developments of the Cotton Spinning Industry in Japan. The 1st International Conference on Business & Technology Transfer (ICBTT 2002). Retrieved on 2025-06-12.

Ōsaka Bōseki Kabushiki Kaisha (大阪紡績株式会社) is known in English as Osaka Cotton Spinning Company, or Osaka Spinning Company.

Tsurumi E. Patricia (1990). Factory Girls: Women in the Thread Mills of Meiji Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 38–40.

Fascinating reading that filled me in on Osaka’s interesting past! Thanks so much for putting all of this together and sharing it.

Fascinating. Never knew most of the info.