Japan's Cotton Revolution

Humble cotton helped transform Japan from a feudal into an industrialized nation

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

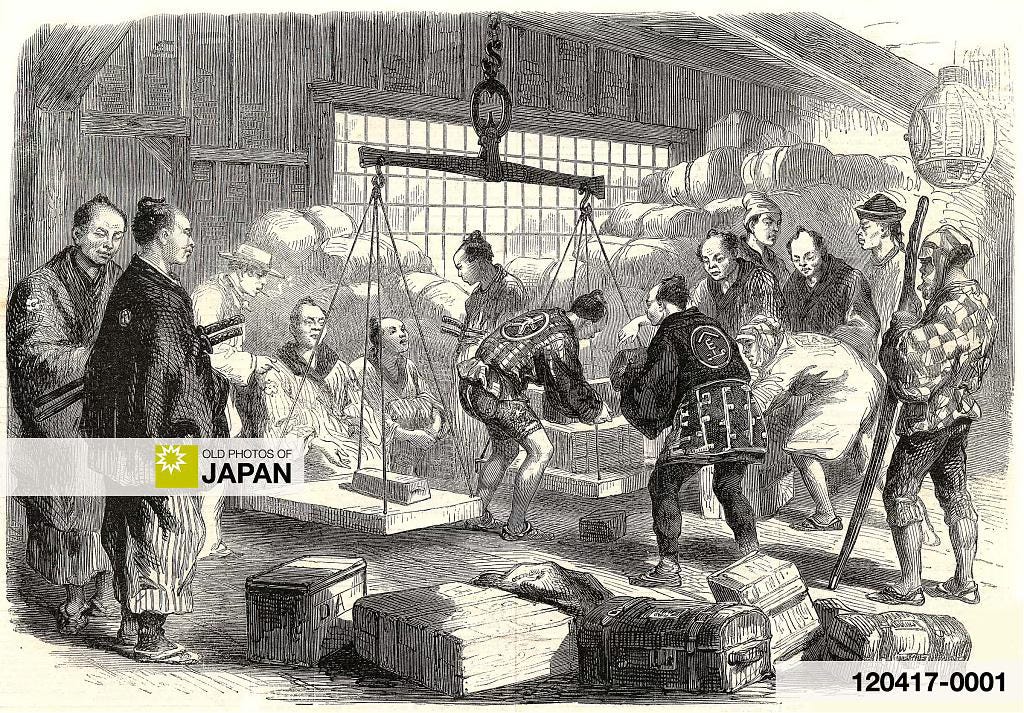

Interior of the Toyobo cotton mill in Osaka’s Sangenya area in 1929. Cotton mills played a crucial role in transforming Japan from a feudal into an industrialized nation. Toyobo started off this revolution.

Introduction

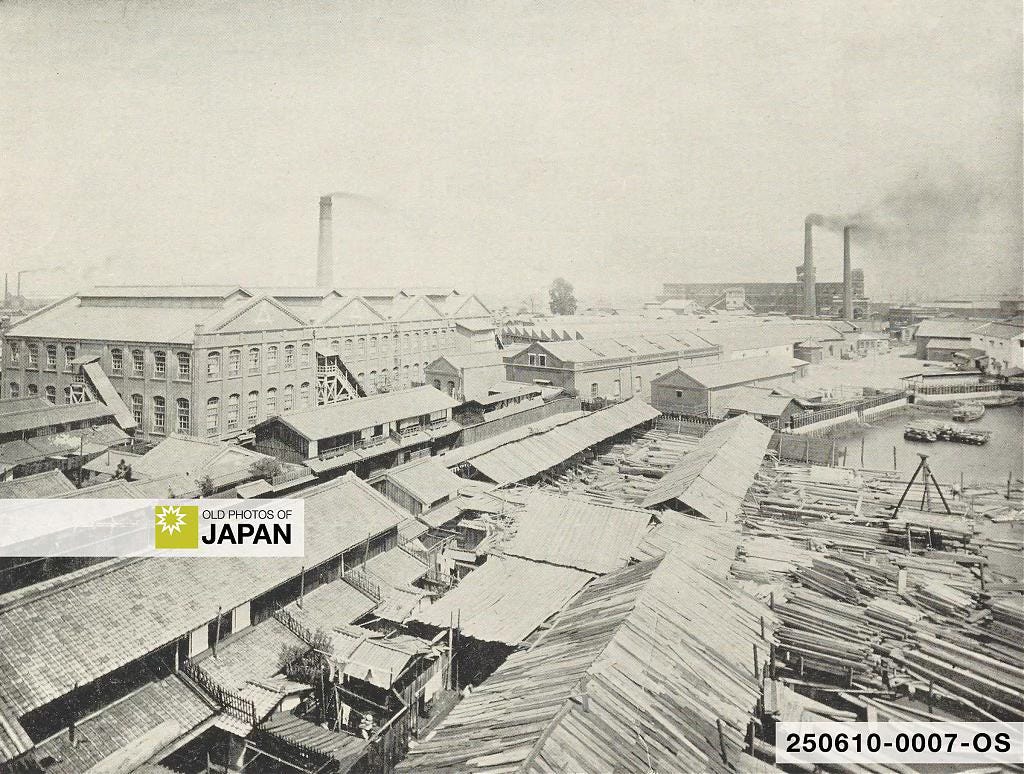

In City of Smoke, we discovered how 1920s Osaka was dominated by smokestacks shrouding the city in an almost perpetual “cloud of smoke.” Many smokestacks belonged to the city’s thriving textile industry. By 1927 (Showa 2), the city was home to some 24 spinning mills employing 24,200 workers, roughly 12% of the city’s workforce. They generated 80% of the city’s industrial output by value.

One company played an influential role in creating this exceptional situation: Osaka Bōseki, later known as Toyobo.1 In 1883 (Meiji 16), it started operating Japan’s largest cotton mill in Osaka’s Sangenya district. Equipped with 10,500 spindles, it was nearly five times larger than Japan’s next largest mill.2 Over the following decades, Osaka Bōseki helped Japan transform into a major cotton exporter and a modern industrial power, with Osaka as its economic heart.

Hands-On, Hands-Off

Osaka Bōseki was the brainchild of the influential industrialist Eiichi Shibusawa (渋沢栄一, 1840–1931). As key economic modernizer he helped establish, or was involved with, some 500 enterprises during his lifetime. Notably, Japan’s first modern bank (1873) and the Tokyo Stock Exchange (1878).3 He was also involved in founding some 600 organizations, including the Japanese Red Cross, Japan Women’s University, and Japan’s national scientific research institute, RIKEN.

An impressive 167 companies operating today trace their roots to a business founded or managed by Shibusawa. These include prominent corporations such as Eneos, MUFG, Mitsui & Co., SMBC, and KDDI.4 Since July 2024 (Reiwa 6), his portrait graces the 10,000 yen note, Japan’s highest banknote denomination.

Shibusawa’s fierce pursuit of economic modernization was sparked during a year-and-a-half visit to Europe as part of a shogunal delegation to the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris.5

Compared to Europe, Japan’s economy lagged far behind in technology and industrial capability. Shibusawa was stunned by the advanced textile factories, dockyards, ironworks, and other industries he inspected in Europe.

He was also impressed by legal and social systems, particularly the joint stock company model, which allowed more effective enterprise through cooperation. It enabled a scale of industrial organization that was impossible under individual capitalization. Europe’s dynamic economy convinced him that Japan’s future depended on advancing commerce, industry, and technology.6

The timing of Shibusawa’s trip was significant. Only eight years earlier, in 1859 (Ansei 6), Japan had ended over two centuries of isolation by opening three ports to foreign trade.7 These were cautious steps, and in 1867 (Keiō 3), most of the country was still closed off to foreigners. Few Japanese went abroad.

Crucially, during Shibusawa’s visit to Europe, the Meiji Revolution erupted. The fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate marked a major political shift, opening the doors of the country’s government to new people and radically different ideas.

Some time after returning to Japan, Shibusawa joined the newly formed Meiji government at the Ministry of Finance, where he was in charge of reform. He resigned in 1873 (Meiji 6) to become president of the First National Bank (第一国立銀行, Dai-Ichi Kokuritsu Ginkō), which he had helped establish at the ministry. The bank became his base for launching and encouraging modern companies.

Shibusawa’s remarkable success was rooted in his distinctive business philosophy and management style. Profit and commerce had been viewed with suspicion in Japan. Shibusawa, in contrast, was in favor of the profit motive. However, he firmly believed that morality and economics were inseparable, and that the ultimate objective of business should be to serve the public good. His guiding principle can be summarized as: “public interest first, private profit second.”8

The criteria for Shibusawa when he developed entrepreneurial activities was whether or not they were necessary for the state rather than whether or not they would prove lucrative for him; he put public interest before private profit. Nevertheless, he did not completely disregard private profit.

Kazuhiro Tanaka, 2020

Shibusawa’s philosophy extended to social relief and public welfare. Scottish economist and philosopher Adam Smith (1723–1790) argued that wealth would naturally trickle down through the “invisible hand” of the market, even if the rich acted out of self-interest. Shibusawa, however, insisted that deliberate actions were essential to address the inequality between the rich and the poor.9

Even when you have become wealthy, first of all, be aware of your debt to society. If you constantly take the lead and spare no effort on behalf of social relief or public welfare, society will become doubly sound, and at the same time, the management of your own assets will also become increasingly solid. But, if the wealthy ignore society, thinking that they can preserve their wealth by distancing themselves from society, disregarding the social and public welfare, this is where the collision between the wealthy and people in society will take place.

Eiichi Shibusawa, 2008

In recent decades, Shibusawa’s philosophy of gapponshugi (合本主義) attracts renewed interest from economic scholars and business leaders for answers to capitalism’s challenges. Institutions like Harvard Business School have been publishing research on the concept.

Another key factor in Shibusawa’s success was his management style. His approach was more visionary than operational. As a director, advisor, and major shareholder, Shibusawa was rarely involved in the day-to-day management of the businesses he supported. Instead, he acted as a catalyst — lending his name, mobilizing capital, guiding through technical knowledge, and identifying potential talent.

Shibusawa was hands-on in suggesting solutions for Japan’s economic and social challenges, securing financing, and finding the right people. But when it came to daily management, he was deliberately hands-off.10

Dreaming Big

The plan for Osaka Bōseki was born in 1879 (Meiji 12) after Shibusawa discovered that cotton imports made up an unsustainable 36% of Japan’s total imports. It was clear that the country needed to develop its own spinning industry.

The Meiji government was promoting and building mills with 2,000 spindles at the time. But Shibusawa calculated that to turn a profit, a mill required at least 10,000 spindles.11 He successfully secured funding and persuaded Takeo Yamanobe (山辺丈夫, 1851–1920), a promising economics student studying in London, to redirect his studies to spinning mill engineering.

Yamanobe transferred to the mechanical engineering department at Kings College, Cambridge and later gained practical skills at Rose Hill Mill in Blackburn, near Manchester, working alongside regular mill workers. Upon returning to Japan, he became Osaka Bōseki’s chief engineer, making key strategic decisions like site selection, mill design, and machinery procurement.12

Osaka Bōseki began operations on July 5, 1883 (Meiji 16). By December of that year, 7,000 spindles were running, staffed by 64 male and 224 female workers. By the spring of 1884, all spindles were in use.13

Remarkably, the company was profitable from the start, enabling it to triple its capital within a few years and expand. By 1886 (Meiji 19), it powered over 30,000 spindles, over 10 times more than other mills. It now produced 46% of all cotton yarn in Japan. Profits surged.

This marked a turning point. For the first time since the first cotton mill opened in Kagoshima in 1867 (Keiō 3), Japan had successfully commercialized mechanized cotton production. Realizing that the industry developed better on its own, the government withdrew its ineffective support to the cotton industry.14

Osaka Bōseki’s success provided valuable lessons. Notably, the vital importance of selecting the right technology and the powerful impact of uniting Shibusawa’s strong leadership with Yamanobe’s insightful practical expertise. It demonstrated that simply getting the latest machinery could not deliver desired results.

Earlier mills failed especially due to limited capital, lack of technical expertise, inefficient production scales, and reliance on water power. The latter not only restricted mills to remote locations, causing logistical headaches, but also led to recurring seasonal power shortages. In response, Osaka Bōseki implemented a number of crucial innovations:15

Financing

To solve the issue of insufficient capital, the company was financed as a joint-stock company, supplemented with loans from Shibusawa’s First National Bank.

Technical Expertise

Shibusawa’s success in persuading Yamanobe to study cotton mill technology in the UK proved decisive. It brought Osaka Bōseki a chief engineer with practical experience, able to select and manage advanced machinery suited to Japan. Structured technical training for staff further strengthened this edge.

Steam Power

Steam power let the company set up in Osaka, an urban hub with ample access to workers, transport links, and support services. It also allowed the costly machines to run around the clock, boosting output without extra investment. This greatly improved return on capital.

Cost Reduction

By installing five times more spindles than earlier mills, Osaka Bōseki cut costs through scale. It also kept expenses down by using low-priced Chinese cotton instead of domestic supplies.

One troubling cost cutting measure seems to have been the most influential. Despite Shibusawa’s promotion of social welfare, the company paid painfully low wages. The site in Osaka was actually chosen in part for its access to a large pool of urban poor and struggling farm families in the surrounding area.

Male workers were paid about half the wages of skilled urban tradesmen like carpenters and stone-masons. Women earned barely half of that. Osaka Bōseki placed mill workers at the lowest rung of the employment ladder, workers’ wages were barely enough to survive, let alone thrive.16

Osaka Cotton-Spinning’s relationship with its hands definitely was not imbued with the “master-vassal” notions that apparently united employees and bosses in many of the smaller plants. Profits were seen as the key to the future envisioned by Shibusawa. On 5 July 1883, when Osaka Cotton-Spinning began partial operations, its hard-boiled approach to hiring differed sharply from practices of other companies. Some mills, especially those located in remote regions, provided dormitories or boardinghouses for their workers; at Osaka Cotton-Spinning in 1883, all the hands were commuters. The company did not intend to “waste” money on housing or other amenities for workers. Predictably, the wages offered were lower than those paid at most other cotton companies.

E. Patricia Tsurumi, 1990

Cotton Revolution

As Osaka Bōseki’s profits surged, other companies embraced its model. In 1886, Japan had 21 cotton mills. By the end of the decade, that number had doubled. It doubled again by 1898 (Meiji 31). Production increased even more dramatically. Between 1890 (Meiji 23) and 1899 (Meiji 32), spindle count quadrupled, while output increased ninefold.17

Osaka, where many of these companies built their sprawling factories, was on fire. In 1896 (Meiji 29), American journalist William Eleroy Curtis (1850–1911) described Osaka as “the Chicago of Japan, a miracle of progress and industry.”18

The sudden explosion of new companies unleashed a brutal wave of competition with relentless cycles of innovation and knowledge exchange. As technological and managerial breakthroughs spread like wildfire, turbulent business cycles intensified the pressure. Poorly managed firms — even large ones — were swept away or gobbled up. By 1904 (Meiji 37), only 49 companies remained.19

The intense competition and innovation drove imported yarn out of the Japanese market and British textile products out of Asia, Japanese firms taking over most of the Asian market. As the industry grew, it moved both upmarket (higher-quality products) and downstream (fabric weaving and finished goods).20

By 1933 (Showa 8), Japan had become the world’s largest cotton producer, making 41% of global cotton goods.21 Cotton mills had become a cornerstone of Japan’s economy, producing more than a quarter of the nation’s industrial output and employing over 40% of its factory workers.22 The industry’s remarkable growth served as a catalyst for development in other sectors of Japan’s economy, notably heavy industry. Here Osaka played a major role as well.

Osaka Bōseki especially stood out in this sweeping cotton revolution. Following a name change to Toyobo in 1914 (Taisho 3) and a series of successful mergers it grew into the world’s largest cotton-spinning company during the 1930s.23

A 1933 English-language business directory vividly illustrates how much of Japan’s cotton industry was concentrated in Osaka. It listed 23 cotton mills in Osaka, nearly double Tokyo’s 12. Nagoya came in third with 11 mills.

The directory also listed 175 Osaka-based businesses connected to the cotton trade, such as exporters, importers, merchants, manufacturers of piece goods, wholesalers, etc. Tokyo listed only 43, less than a quarter of Osaka’s total.

Osaka had become Japan’s undisputed cotton capital.

Stone Monument

Osaka Bōseki’s significant impact is commemorated by a stone monument on its former site, bearing the words: Birthplace of the Modern Spinning Industry. It is arguably one of the cradles of Japan’s modern industry as a whole.

Notes

Want to know more about the people, organizations, or sources introduced in this article? The original article on Old Photos of Japan features many links!

Osaka Bōseki Kabushiki Kaisha (大阪紡績株式会社) is known in English as Osaka Cotton Spinning Company, or Osaka Spinning Company.

Tsurumi E. Patricia (1990). Factory Girls: Women in the Thread Mills of Meiji Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 38–40.

Hoover, William D. (2002). Shibusawa Eiichi: The Businessman as Public Figure. Journal of Japanese Trade & Industry, March/April 2002, 32–35. Retrieved on 2025-06-14.

The first commercial bank was The First National Bank (第一国立銀行, Daiichi Kokuritsu Ginkō).

Shibusawa was not only active as an economic modernizer. He was also involved in social welfare, international relations, education, and culture.

株式会社帝国データバンク 情報統括部長 藤井俊 (2024-07-01)『 新一万円札の肖像・渋沢栄一設立に関わり現存する企業は 167 社 ~ 売上高トップは ENEOS、業歴トップは三越伊勢丹 ~』TEIKOKU DATABANK, LTD., TDB Business View. Retrieved on 2025-06-15.

Shibusawa visited France, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and Great Britain.

Hoover, William D. (2002). Shibusawa Eiichi: The Businessman as Public Figure. Journal of Japanese Trade & Industry, March/April 2002, 32–35. Retrieved on 2025-06-14.

Hakodate, Yokohama, and Nagasaki. Kobe and Osaka were opened in 1868 (Keiō 4), and Tokyo (Tsukiji) and Niigata in 1869 (Meiji 2).

Tanaka, Kazuhiro (2020). Prioritizing Public Interest: The Essence Of Shibusawaʼs Doctrine and its Implications for the Re-Invention of Capitalism. Hitotsubashi Journal of Commerce and Management, Vol. 53, No. 1 (February 2020), 1-19.

“But Shibusawa, who lived in Japan from the 19th to the 20th century, is not the only one to advocate the compatibility of morality and economics. For example, Adam Smith in 18th century Scotland and Michael Porter in the United States of the 21st century have made similar assertions. Comparing their opinions with Shibusawaʼs opinion, however, also turns up some inherent differences. Similarly to Smith and Porter, Shibusawa is fully in favor of the pursuit of private profit, but unlike them, he emphasizes that business should be conducted with public interest as the intended and primary objective in itself.”

“In a speech recorded in 1923, Shibusawa himself said that his doctrine and Adam Smithʼs view were aligned with each other, and that he therefore believed that the inseparability of morality and economy is an immutable principle that applies in both the East and the West.”

Shibusawa himself used the phrase “the Analects and the abacus are inseparable,” referring to Confucius’ Analects and the traditional calculating tool, the abacus.

渋沢 栄一 (2008). 『論語と算盤』東京:角川ソフィア文庫, 147. English translation via Tanaka, Kazuhiro (2020). Prioritizing Public Interest: The Essence Of Shibusawaʼs Doctrine and its Implications for the Re-Invention of Capitalism. Hitotsubashi Journal of Commerce and Management, Vol. 53, No. 1 (February 2020), 9.

Hoover, William D. (2002). Shibusawa Eiichi: The Businessman as Public Figure. Journal of Japanese Trade & Industry, March/April 2002, 32–35. Retrieved on 2025-06-14.

日本経済史研究会 (1955). 『近代日本人物経済史 上巻』東洋経済新報社, 196.

Braguinsky, Serguey (2015). Knowledge Diffusion and Industry Growth: The Case of Japan’s Early Cotton Spinning Industry. ISER Discussion Paper, No. 939. Osaka: Osaka University, Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER), 16–17.

Yamanobe became president of Osaka Bōseki in 1898 (M 31). 日本経済史研究会 (1955). 『近代日本人物経済史 上巻』東洋経済新報社, 212.

日本経済史研究会 (1955). 『近代日本人物経済史 上巻』東洋経済新報社, 201.

Ohno, Kenichi (2018). The History of Japanese Economic Development: Origins of Private Dynamism and Policy Competence. New York: Routledge, 64–65.

Also: Braguinsky, Serguey (2015). Knowledge Diffusion and Industry Growth: The Case of Japan’s Early Cotton Spinning Industry. ISER Discussion Paper, No. 939. Osaka: Osaka University, Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER), 18.

In 1887, the company booked a return on invested capital (ROIC) of over 55%. 石井寛治, 原朗, 武田晴人 (2000)『日本経済史. 2』東京大学出版会, 120.

Ohno, Kenichi (2018). The History of Japanese Economic Development: Origins of Private Dynamism and Policy Competence. New York: Routledge, 64–65.

Also: Braguinsky, Serguey (2015). Knowledge Diffusion and Industry Growth: The Case of Japan’s Early Cotton Spinning Industry. ISER Discussion Paper, No. 939. Osaka: Osaka University, Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER).

Tsurumi, E. Patricia (1990). Factory Girls: Women in the Thread Mills of Meiji Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 41–42.

Braguinsky, Serguey (2015). Knowledge Diffusion and Industry Growth: The Case of Japan’s Early Cotton Spinning Industry. ISER Discussion Paper, No. 939. Osaka: Osaka University, Institute of Social and Economic Research (ISER), 18.

日本経済史研究会 (1955). 『近代日本人物経済史 上巻』東洋経済新報社, 211.

Curtis, William Eleroy (1896). The Yankees of the East: Sketches of Modern Japan. New York: Stone & Kimball, 6.

Ohno, Kenichi (2018). The History of Japanese Economic Development: Origins of Private Dynamism and Policy Competence. New York: Routledge, 65.

ibid, 49.

Japanese exports were not limited to cotton yarn, cotton clothes, and knitwear, but also included light manufactured goods such as matches, umbrellas, clocks, lamps, glass products and so on. Ohno, Kenichi (2018). The History of Japanese Economic Development: Origins of Private Dynamism and Policy Competence. New York: Routledge, 49–50.

Robinson, Greg (2024). Japan and the U.S. Cotton Trade in the 1930s. Discover Nikkei, Japanese American National Museum. Retrieved on 2025-06-27.

Ramseyer, J. Mark (1993). Credibly Committing to Efficiency Wages: Cotton Spinning Cartels in Imperial Japan. The University of Chicago Law School Roundtable: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 17.

In 1914 (Taishō 3), Osaka Bōseki merged with Mie Bōseki (三重紡績) to form Toyo Bōseki (東洋紡績), popularly known as Toyobo. In 1931 (Showa 6) Toyobo merged with Osaka Gōdō Bōseki (大阪合同紡績). Toyobo is still active today.

Thank you for this inspiring history lesson! That Shibusawa firmly believed “morality and economics were inseparable, and that the ultimate objective of business should be to serve the public good. His guiding principle can be summarized as: “public interest first, private profit second,” is sorely needed in current leaders worldwide.

Great article, Kjeld. Thank you for sharing this information!

In what ways did Shibusawa think that those with higher economic status and power should contribute to social welfare? Did this simply become an afterthought as “the company paid painfully low wages”? The ideal of “public interest first, private profit second” was admirable, but it seems it wasn’t achieved. Or was it?