The New Osaka: New Hotel for a New Era

This rare 1935 pamphlet tells the extraordinary story of an exceptional hotel

Old Photos of Japan is a community project aiming to a) conserve vintage images, b) create the largest specialized database of Japan’s visual heritage between the 1850s and 1960s, and c) share research. All for free.

If you can afford it, please support Old Photos of Japan so I can build a better online archive, and also have more time for research and writing.

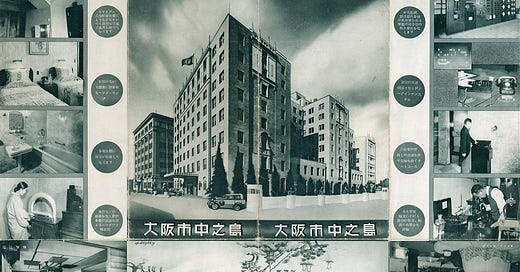

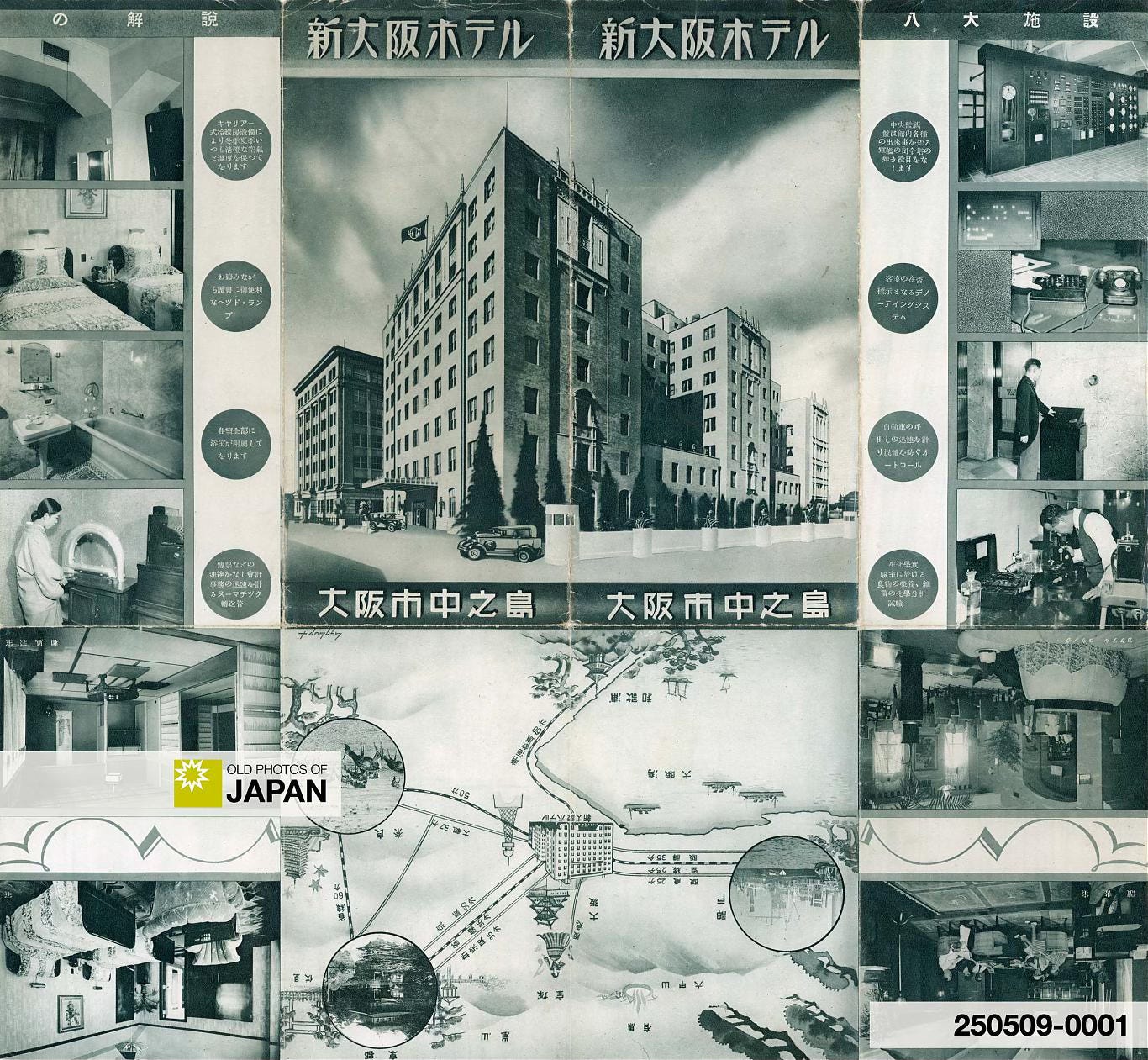

When the New Osaka Hotel opened in 1935, it was one of Japan’s finest hotels. It even boasted air-conditioned guest rooms, a world’s first. This rare pamphlet from its early days offers a fascinating peek inside.

In Osaka’s Nakanoshima: Modern and Vibrant I briefly introduced this pamphlet of the New Osaka Hotel, possibly the hotel’s first. It is a valuable addition to the Duits Collection and I was incredibly fortunate to acquire it.

It is remarkable that this pamphlet has survived to today. How many promotional pamphlets, brochures, and flyers have you received in your life? How many of these do you still have? And how many of these are in good condition?

This pamphlet is actually so special that it deserves a closer look.

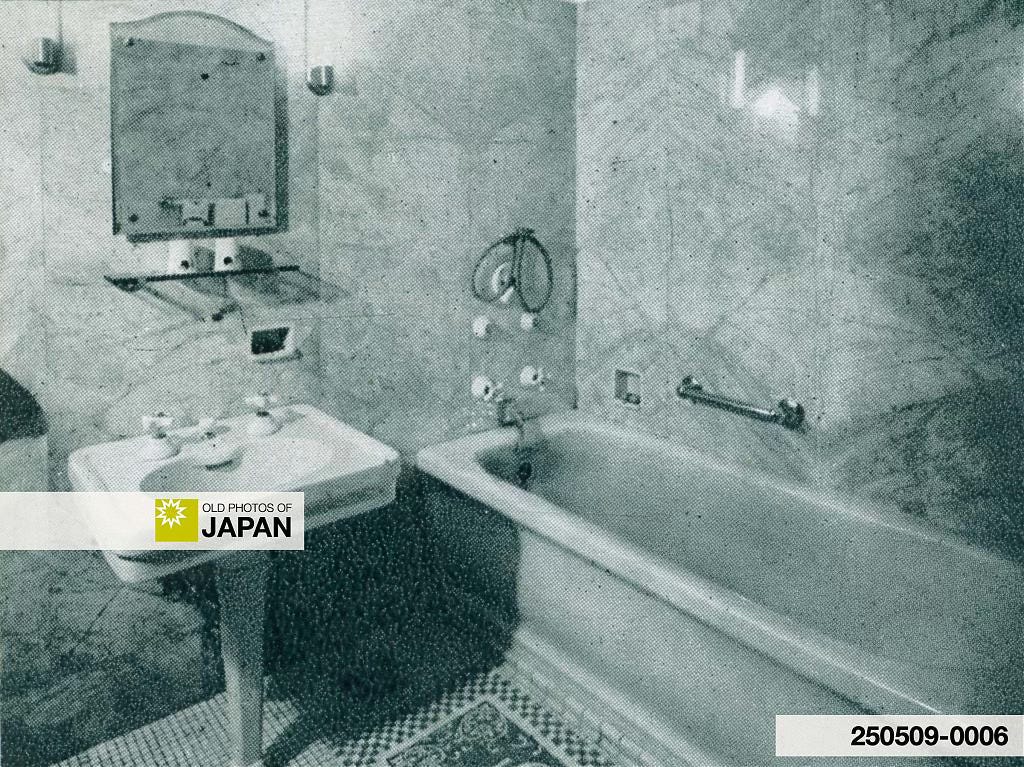

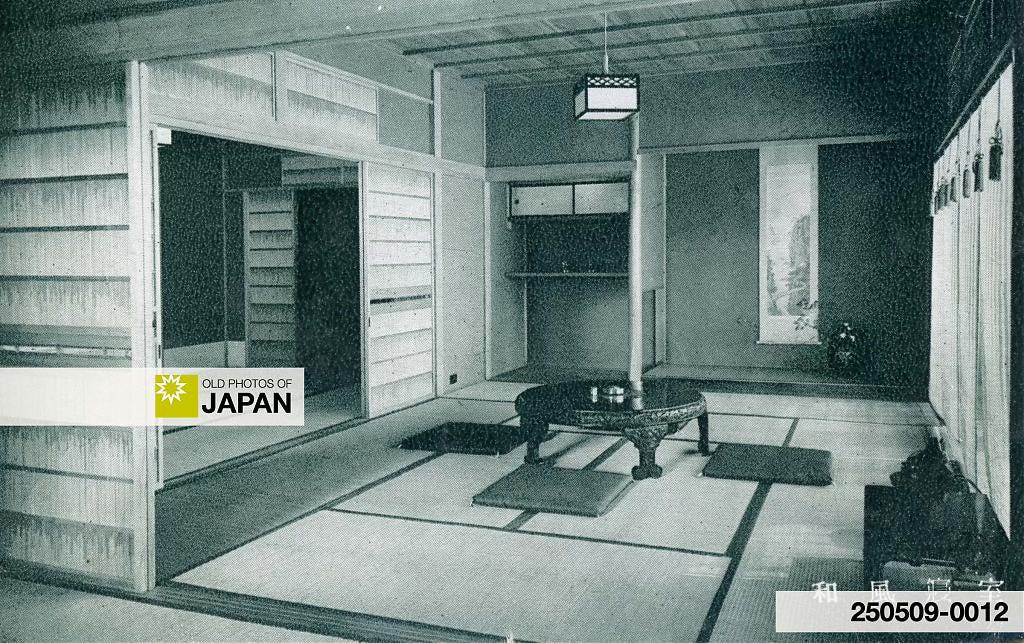

When the New Osaka opened, the luxurious eight-story hotel was cutting edge. It was said to be the largest hotel in the Orient, its furnishings the finest in Japan. The lobby wowed guests with decorative windows and a bandstand, setting an elegant tone. There were ten elevators and 211 guest rooms, including five in traditional Japanese style. Every room had a private bath.

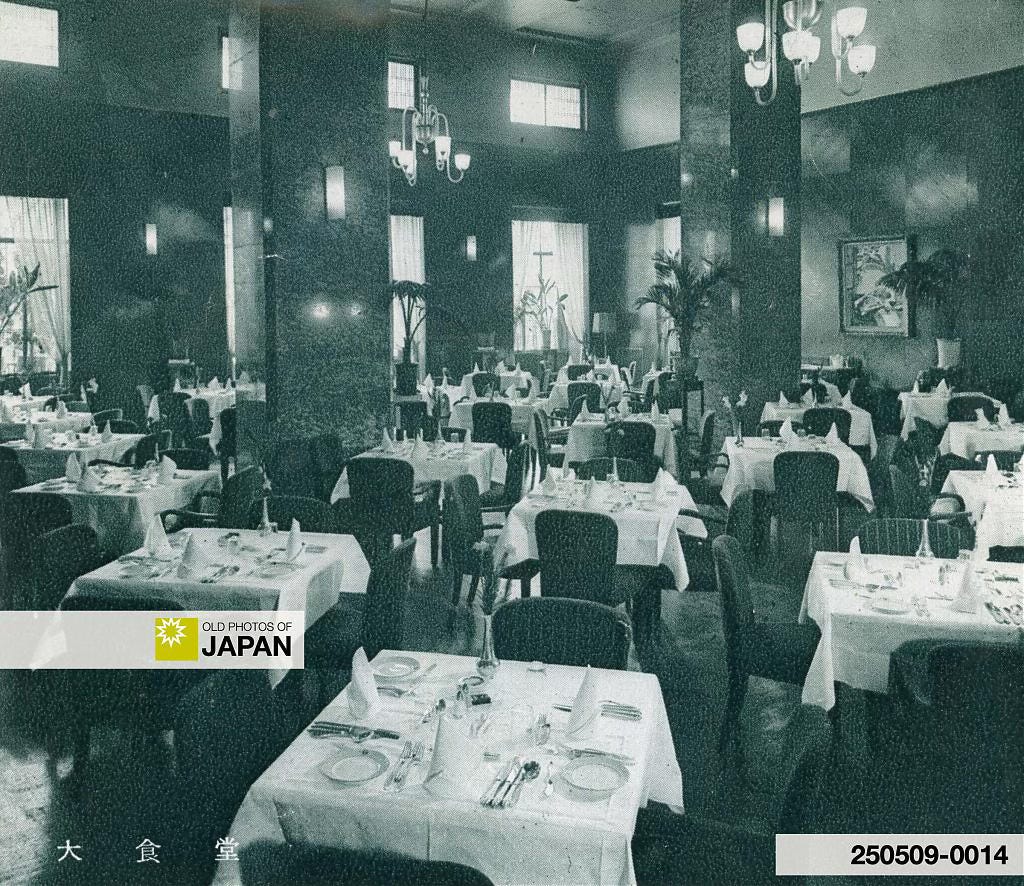

The hotel offered a stunning range of facilities: a spacious banquet hall, a main hall, a standard dining hall, a special dining hall with seating for 500, a grill room, a conference room, and a wedding hall with a Shintō shrine — a feature first pioneered by Tokyo’s renowned Imperial Hotel.1

Construction costs totaled a staggering 6.1 million yen, partially funded by a loan from Japan’s Ministry of Finance. To put this in perspective, that was roughly one-sixth the cost of building the colossal parliament building in Tokyo, which was completed the following year.2

The New Osaka was an instant success. Within its first year, it welcomed more guests than the Imperial, which was Japan’s leading hotel and actually operated the New Osaka. This pamphlet, which showcases many of the hotel’s innovative features, provides a glimpse into what fueled that rapid popularity.

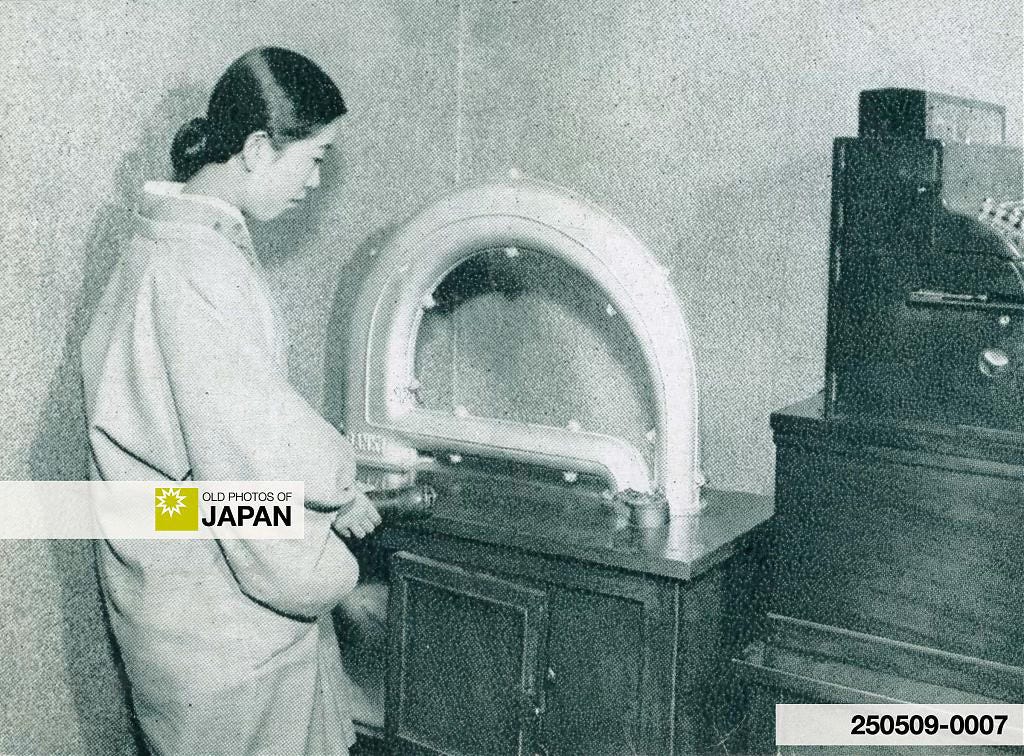

The New Osaka’s most notable innovation was undoubtedly the air-conditioning installed in 25 guest rooms facing south. The hotel’s first manager, Shigeru Gunji (郡司茂, 1897–1977), even mentioned it in his memoirs:3

It may be hard to imagine now, but at the time, not a single hotel in the world offered air-conditioning in guest rooms. There was endless debate about whether or not to install air-conditioning, but Managing Director Kaga made the bold decision to go ahead.

It was a world first, and to our delight, the American magazine Reader’s Digest featured the story. Needless to say, the air-conditioning, which successfully defeated Osaka’s scorching summer heat, was a resounding success.

Shigeru Gunji (1977)

The significance of the air-conditioning system is underscored by its location on the pamphlet; it is shown at the very top.

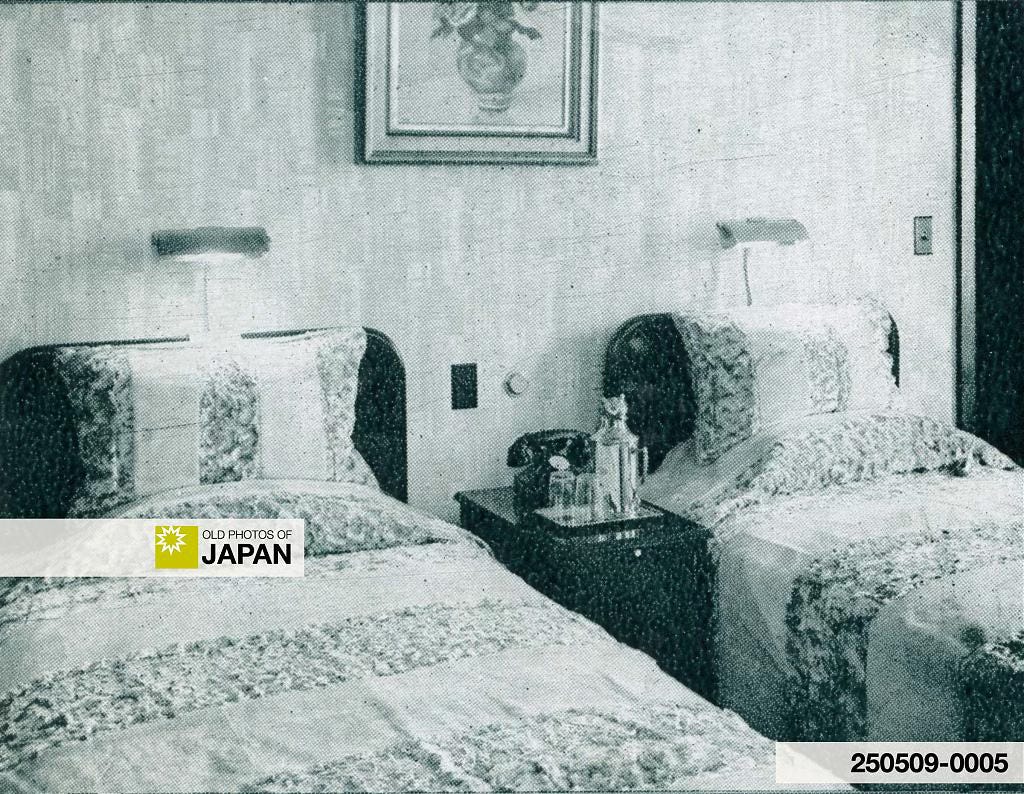

The next two photos may surprise, but in the 1930s an overhead electric light at your bed was a new luxury, as was a private bath. Notice the phone.

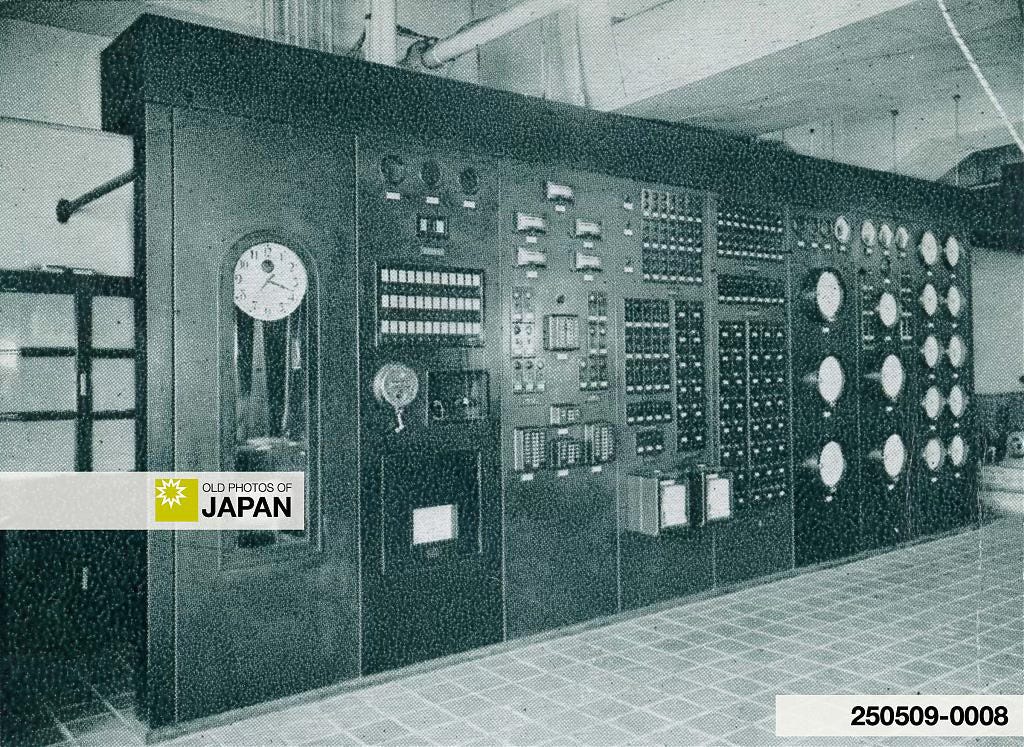

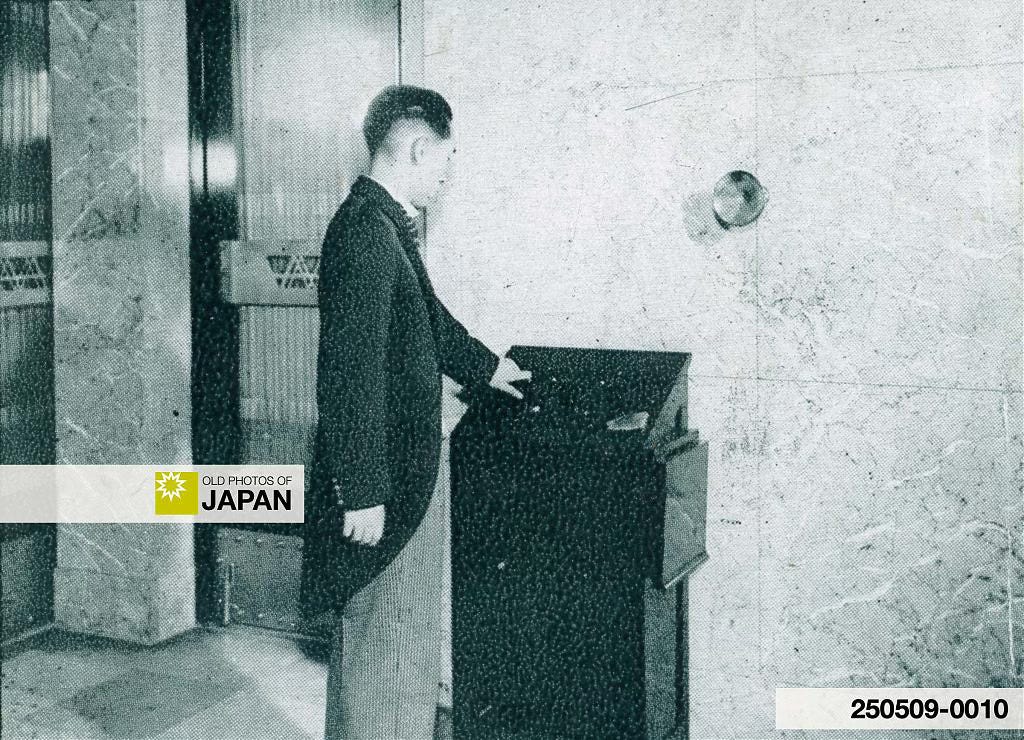

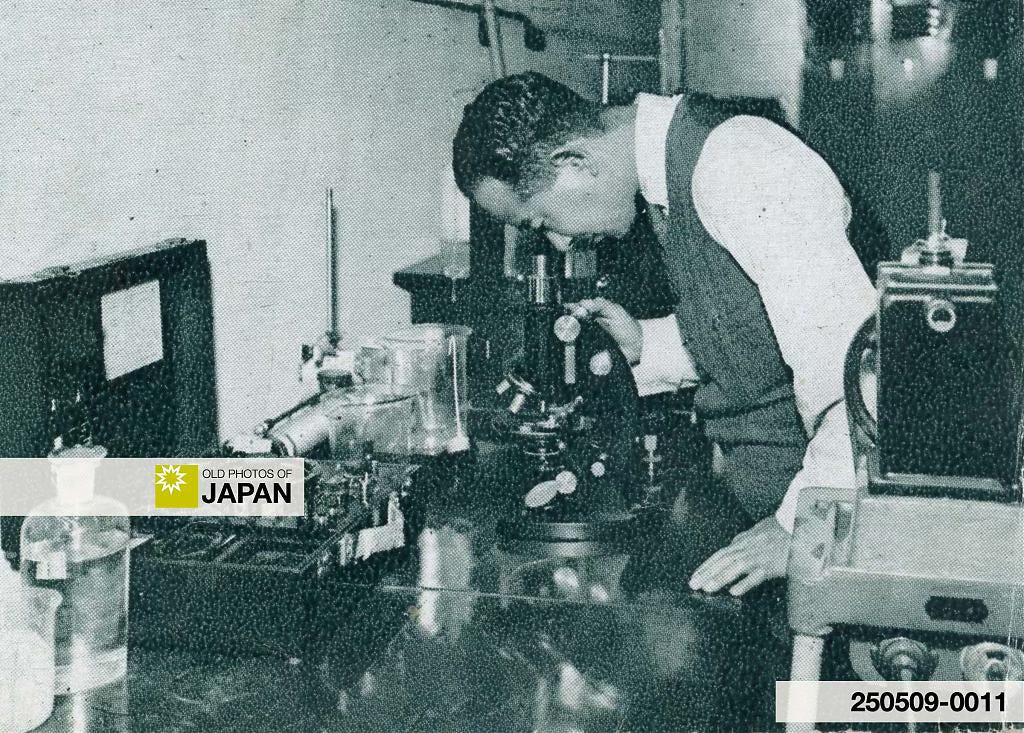

The next five photos are revealing. They all focus on modern technology working behind the scenes to enhance service and safety. A pneumatic tube system moved documents, an electronic panel monitored all building systems, an automated system checked if rooms were available, another called cars, and a laboratory was used to keep food safe.

The latter was clearly needed. Just ten days after its opening, the hotel was hit by a major food poisoning incident that affected 200 guests and made headlines in the newspapers. In his memoirs, former manager Gunji described his shock and bewilderment, as the hotel maintained strict standards for food inspections and cleanliness. A thorough investigation was unable to uncover the cause.4

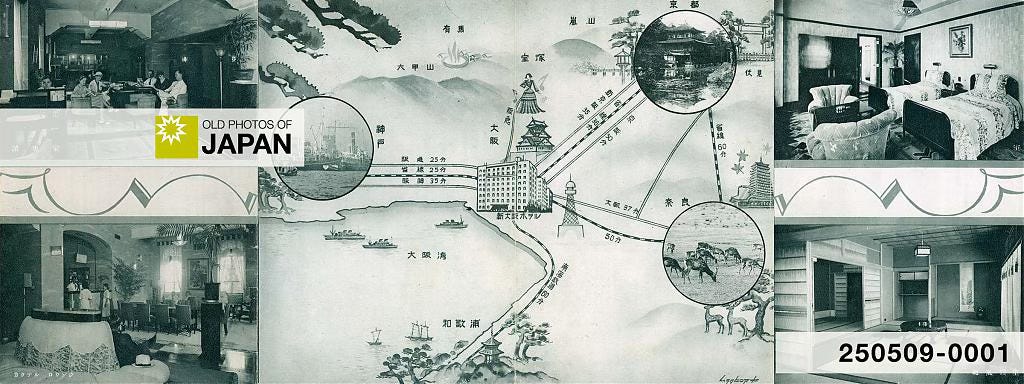

The lower part of the pamphlet’s front page and the entire back page showcase the hotel’s ambiance and elegance, as well as its prime location in the region. The New Osaka was conveniently situated within short train rides from Kobe Port and the historic centers of Kyoto and Nara.

First Class Service

Modern technology, luxurious amenities, and a convenient location all contributed to making the New Osaka one of Japan’s most popular hotels. Gunji, who believed that imitation marked the beginning of decline, especially stressed the importance of innovation. “Creativity is a bold step into the future,” he wrote.5

However, he viewed exceptional service as the key factor to the hotel’s success. He developed a training manual illustrated with photographs titled The Essence of Service (サービスの粋) and oversaw intensive training. Standards were so exacting that a waitress by the name of Ayako Watanabe later recalled being terrified of making a mistake.6

When I first served coffee to customers, my hands were shaking and I felt very embarrassed. It was my first job and I was nervous. I was even more nervous when I thought about making a mistake.

Ayako Watanabe, Waitress

Although Gunji was exacting, he nonetheless encouraged his employees by telling them not to be afraid of failure. “Don’t worry, just do your best.” He also made sure to talk about the achievements of his subordinates rather than his own. This led to extraordinary efforts by the hotel’s employees.7

A girl in the cloakroom noticed that the button on a coat she had been entrusted with was nearly coming off. She silently took out a needle and thread and fixed the button firmly. In foreign countries, it is common in such cases for people to actively point out their actions and even hint for a tip, but she said nothing. This quiet act of service left a deep impression on the coat’s owner, an American who had come to Japan in search of cherry blossoms.

Shigeru Gunji (1977)

Why Osaka?

By the time the New Osaka Hotel opened in 1935, Osaka had established itself as Japan’s industrial powerhouse. The city was brimming with energy, and its economy was thriving.

The idea of building a large Western-style luxury hotel in Osaka was first proposed in 1924 (Taishō 13) by the Osaka Chamber of Commerce and then-Mayor Hajime Seki (關 一, 1873–1935).

That same year, the prominent Osaka Hotel was destroyed by fire. However, Gunji believed that the real impetus was the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 (Taishō 12), which devastated Tokyo, Yokohama, and surrounding areas.8

The Great Kanto Earthquake destroyed most of the top-class Japanese-style inns in Tokyo. As a result, many Osaka businesspeople lost their regular accommodations in Tokyo and had no choice but to stay in hotels such as the Imperial Hotel, which had survived the fires. This experience likely made them acutely aware of the need for a large-scale Western-style hotel in Osaka.

Shigeru Gunji (1977)

Ultimately, it was not the Osaka Chamber of Commerce, but Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel and industrial juggernaut Sumitomo that brought the vision to life. Tragically, Mayor Seki, who had been instrumental in the founding of the New Osaka, passed away only ten days after the hotel opened.

The New Osaka closed its doors in August 1973 (Showa 48). The Royal Hotel, opened in 1965 (Showa 40) and operated by the same management, took over its role as Osaka’s leading luxury hotel.

Hidden Treasures

I acquired this pamphlet from “an 86-year-old senior citizen who collects antiques as a hobby,” as he described himself to me. He lived in a traditional Japanese house a literal stone’s throw away from Shizuoka Prefecture’s mighty Ōigawa River. Surrounded by fields, he spent his days “doing a little bit of farming.”

Over his long life he had collected many thousands of antique items, from vintage maps to teapots. His collection even included a gorgeous lacquered cosmetics box used by a geisha, or perhaps a prostitute. But his collection had overwhelmed him and he was trying to get rid of things.

The antiques I have collected are stored in cardboard boxes in a warehouse, but the boxes have piled up and fill the space. I have thought about getting rid of them, but lately even that feels like too much trouble. My wife always asks me what I am going to do with all these antiques. I think I will end up putting them up for auction.

86-Year-Old 'Senior Citizen'

He called many of his items junk (ガラクタ), but this pamphlet is a small treasure that helps unlock a forgotten past. I am profoundly grateful that I found it and can share it with you. After scanning and studying it, I have carefully preserved the original in my growing collection.

My search for hidden gems continues. If you also value uncovering, studying, preserving, and sharing such treasures, please consider making a donation.

Notes

Ambitions for the New Osaka were high. The hotel was often referred to as the Western Geihinkan (西の迎賓館). A geihinkan is a state guest house used for welcoming foreign dignitaries. 郡司茂(1977).『運鈍根 : ホテルマン50年』毎日新聞社, 76.

郡司茂(1977).『運鈍根 : ホテルマン50年』毎日新聞社, 83–84.

ibid.

ibid.

「含じ難いようであるが、世界広しといえども客室に冷房のあるホテルは、まだ一つもなかったのである。冷房装置をつけるか、どうかについては議論百出したが、加賀常務の英断で実施に踏み切った。世界最初の試みというので、アメリカの『リーダーズ・ダイジェスト』誌がこれを取り上げてくれたのは、大いに愉快であった。大阪の括暑を完全にはねのけた冷房が、大歓迎されたのはいうまでもないことである。」(はねのけた = 撥ね除けた)

By 1935, air-conditioning was already well-known in Japan. As early as 1907, the Fuji Silk Spinning Company installed air-conditioning in its factories. The world’s first fully air-conditioned ships were also Japanese — the Kongo Maru (金剛丸, 1936) and her sister ship Koan Maru (興安丸, 1937).

ibid, 90–91.

ibid, 99.

「真似事は退歩の始まりか、せいぜいよくいって現状維持だ。これに比べ、創造は未来へのたくましい前進だ」と、自分にもいい聞かせ、また人にもいってきた。」

ibid, 79.

「その一人、渡辺綾子さんは「最初、お客さまにコーヒーのサービスの時、ガタガタ手がふるえて、とても恥ずかしく思いました。初めての仕事で緊張していたのです。そそうをしまいと思いますと、余計緊張するのです」と、ウェイトレス事始のころを回想している。」

ibid, 103—104.

「だから、私は容赦なく命令をするが「失敗を恐れるな。君たちの失敗はこの俺の失敗と思って受け止めるから、心配しないで、一生懸命やってくれ給え」といいつづけた。」

「クローク・ルームの一少女が、あずかったオーバーのボタンが、ほとんど取れそうになっているのを発見した。彼女は黙って針と糸を取り出し、ボタンをしっかりと直しておいた。外国ではこういう場合、自分の行為を積極的に主張してチップでも催促するのが普通であるが、彼女は何もいわなかった。この無言のサービスが、オーバーの持主に多大の感銘を与えた。その持主は、日本のサクラを求めて来日したアメリカ人であった。」

ibid, 60.

「関東大震災の時、東京市内で一流といわれる日本式旅館はほとんど全滅し、このため大阪の財界人の多くは、上京の際の定宿を失って、焼け残った洋式の帝国ホテルをはじめ各ホテルを利用せざるを得なくなった。東京での宿泊事情が、彼らに大阪の地にも大規模な西洋式ホテルの必要を痛感させた一因かも知れない。」

So what was the cause of the food poisoning? for those of us who don't have Gunji-san's book

What an incredible find in coming into possession of that pamphlet! And such an elegant hotel. Great history here, Kjeld. Thank you for sharing it with us!