A devastated landscape, almost everything burned to the ground. This is Yokohama after the Great Kantō Earthquake of September 1, 1923, this year exactly one century ago. How could anybody have survived?

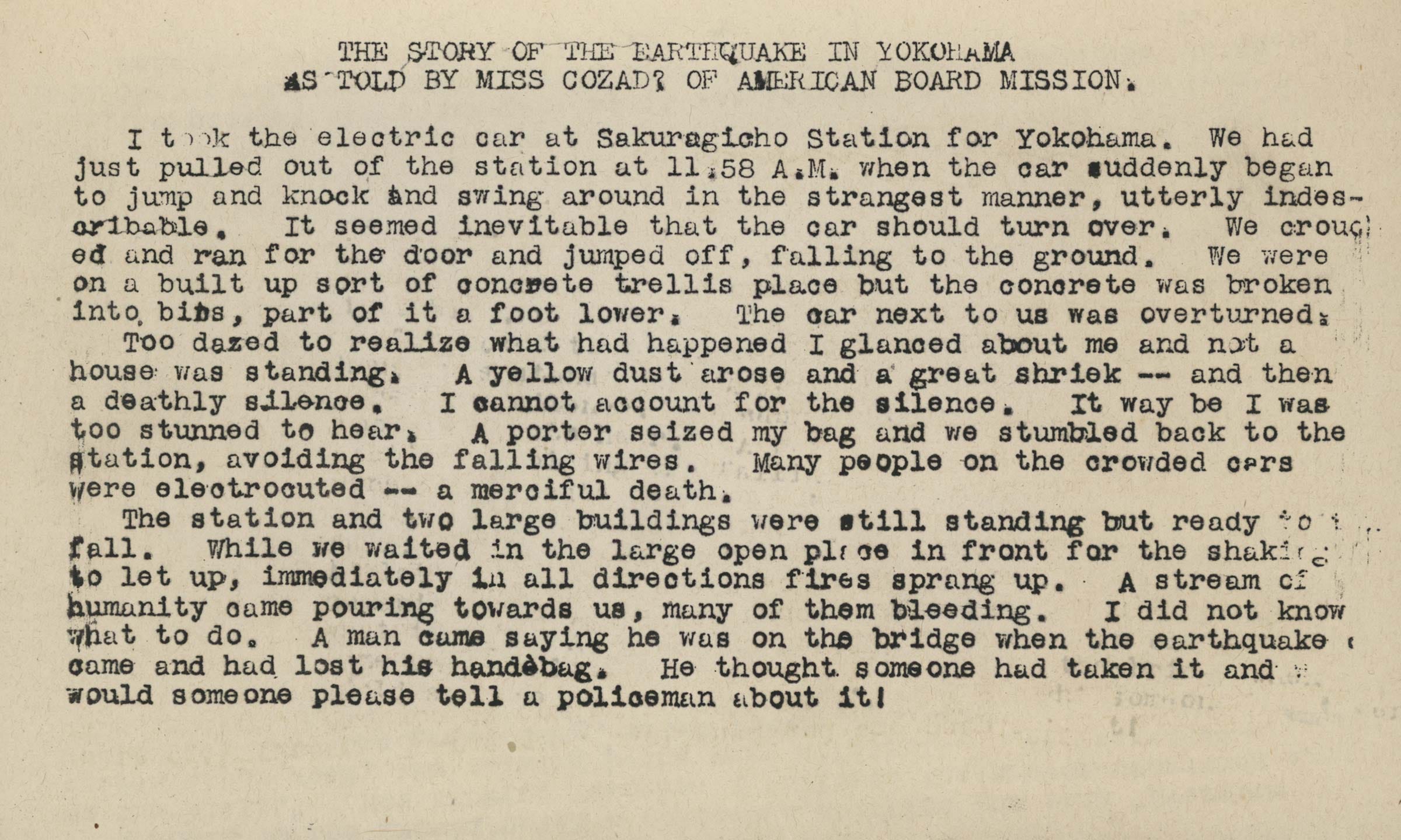

In 2011 I purchased a few unassuming typed pages with the story of one of these survivors, Gertrude Cozad (1865–1949). The then 58-year-old principal of the Women’s Evangelistic School in Kobe, now integrated into Kwansei Gakuin University, was visiting the sprawling harbor city when the quake hit.1

Cozad typed the pages on September 6th, just a few days after surviving her ordeal. This makes her story very direct. I will therefore share her words as she typed them.

What makes Cozad’s account especially valuable is that she describes how the Japanese around her were dealing with the disaster. It is not just about her and the devastation. Her story is about the inhabitants of Yokohama. Tragically, most of the people she so vividly describes perished soon after she met them. She barely escaped the same fate herself.

Cozad later wrote a more detailed report and deposited it at the library of the Boston Athenæum in 1924. Here it remained unopened until well into the present century.

I have not been able to locate any other copy of the report that I have, so this might be the first time since 1923 (Taisho 12) that it is published.

Cleveland Missionary

Before we dive into Cozad’s dramatic report, a little background to better understand what kind of person Cozad was. She was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1865 (Genji 2) to a locally influential family. Her background suggests a socially and economically progressive environment.

Gertrude’s father Justus worked as a civil engineer for the railways at a time when they were revolutionizing American society and opening up the nation. By the 1870s railways had become the second-largest employer in the U.S. (after agriculture).2 Railway engineers like Justus were in demand and were paid well.

An even more revealing aspect of Cozad’s background is that her family was abolitionist, they strove to end slavery. Through the mid-19th century Cleveland was an important stop on the Underground Railroad and a hotbed of abolitionist activity. Several family members were actively involved in the movement.

Since 2021 Justus Cozad’s former house represents this history. Known as the Cozad-Bates House, it has been transformed into an “interpretive center” housing exhibits about slavery and abolitionism.3

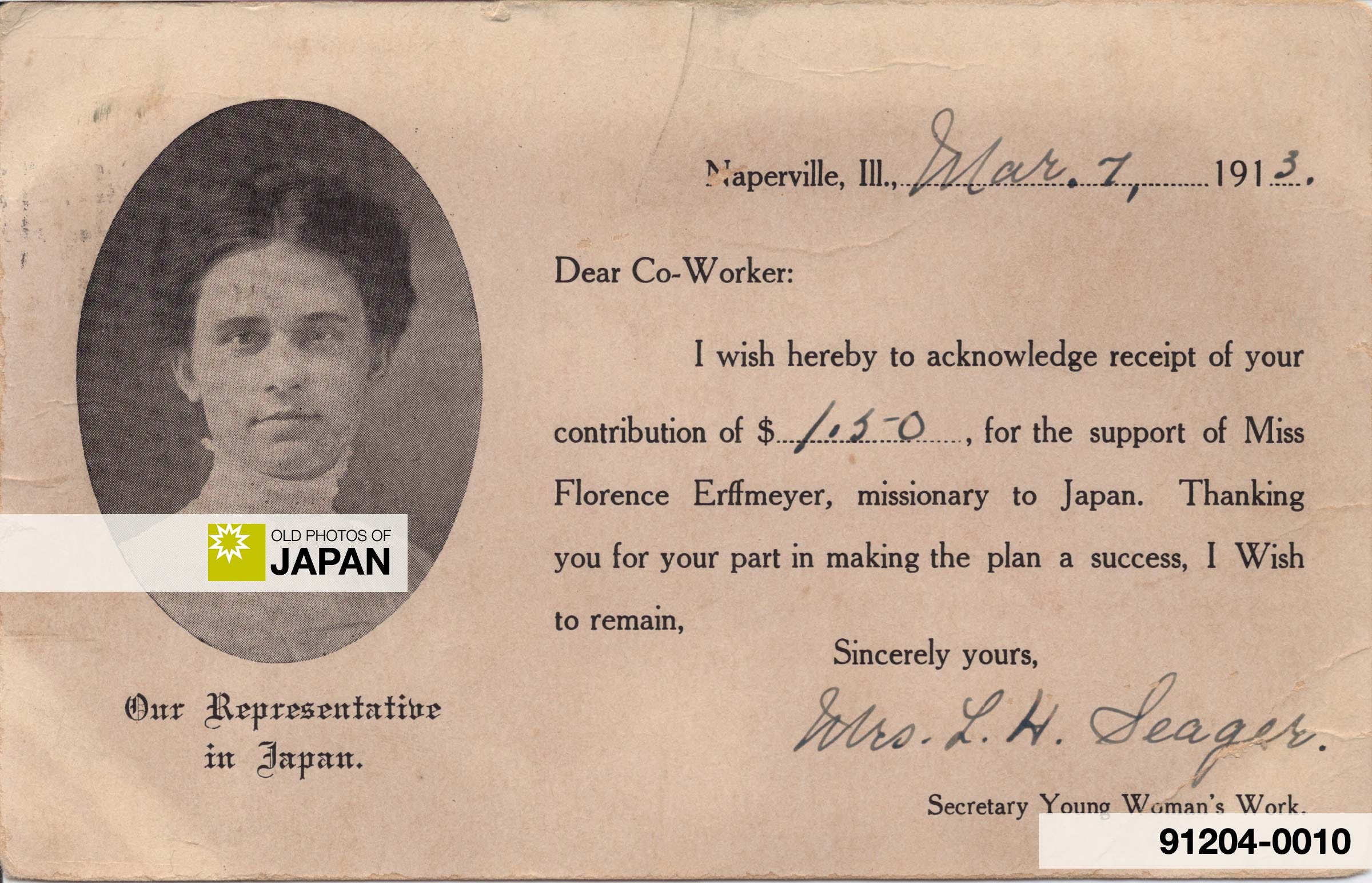

Gertrude Cozad graduated from Cleveland-based Adelbert College at Western Reserve University in 1887 (Meiji 20) during one of the first U.S. waves for higher education for women.4 American education, and that of other Western nations, may have been opening up to women, most of society was not. Missionary work was one of the few professions where well-educated and ambitious single women were given opportunities and many women chose the work as their vocation.5

One of the striking features of the American foreign missionary force in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was that women composed about sixty percent of it. Some were missionary wives (most of whom played active roles in the mission), but many were single women missionaries. It may be true that women could find more challenging and satisfying vocations on the foreign mission field than they could at home during these decades.

Daniel H. Bays, The Foreign Missionary Movement in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

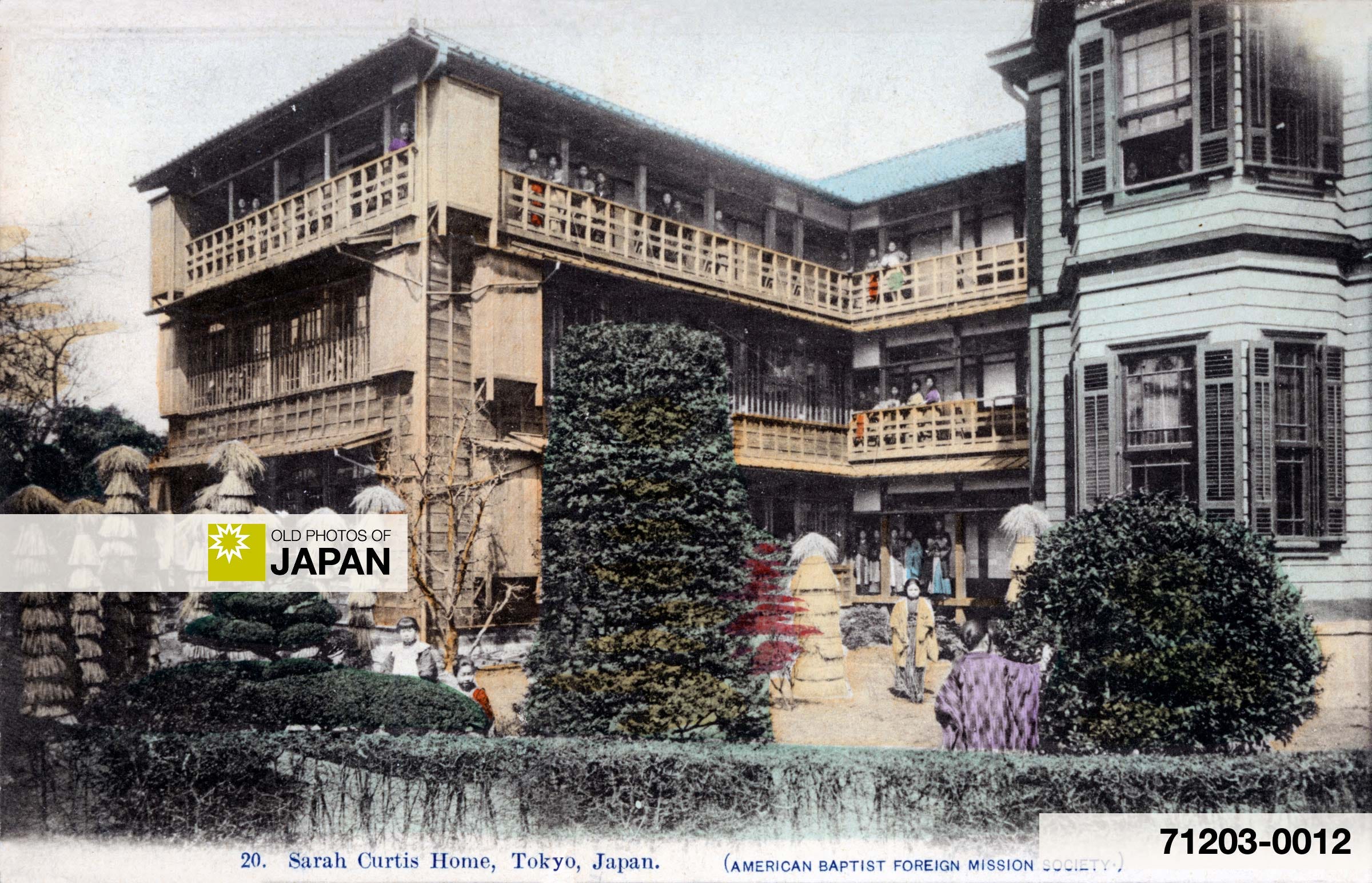

American missionaries spread a special kind of gospel. They fused the Protestant responsibility to evangelize with the belief that the U.S. was an exemplary model of “civic virtue and republican civilization.”6 Additionally, a large number of the missionaries that came to Japan had a very specific goal—educate and emancipate Japanese women. Until the Second World War, top academic programs in women’s education in Japan were offered mostly by mission schools, not the Japanese government.7

Mission schools grew like mushrooms in Japan. By 1882 (Meiji 15)—only nine years after Japan had removed its strict proscriptions against Christianity—Protestant missionary organizations had already established “9 schools for boys, 15 for girls, 39 coeducational institutions and 7 theological seminaries.”8 By 1908 (Meiji 41), missionaries were running 186 Protestant schools, 51 Catholic schools and 3 Greek Orthodox schools. They were educating over 25,000 students.9

Many of the teachers at these schools, and even the principals, were women. During the first years of the prestigious Aoyama Jogakuin (青山女学院) all principals and superintendents were women, mostly single.10

Many of these organizations still exist in some form today. The list of Japanese universities founded by Christian missionaries is surprisingly long. Astonishingly, a large number were originally funded by tiny donations from hundreds of thousands of nameless Christians, mainly in the U.S. and Canada.

Cozad was one of the women choosing a missionary career. She arrived in Japan in August 1888 (Meiji 21) and only four years later became the head of the Women’s Evangelistic School in Kobe, the first training school for Japanese Christian women workers.

Cozad did not limit herself to missionary and educational work. In 1918 (Taisho 7) she wrote a well-researched and popular book about the history of Kobe, The Romance of Kobe. She retired in 1926 (Showa 1), a mere three years after the devastating earthquake.11

Cozad was well-educated, and socially engaged. She was confident and had an advanced ability to get things done. She was aware of, and interested in, the needs of those less privileged than herself. On that fateful day in September 1923 she had lived, worked, and widely travelled in Japan for 35 years. She knew the country, culture, and people well, and spoke Japanese. This background influenced how she responded to, experienced, and reported the disaster.

The Quake

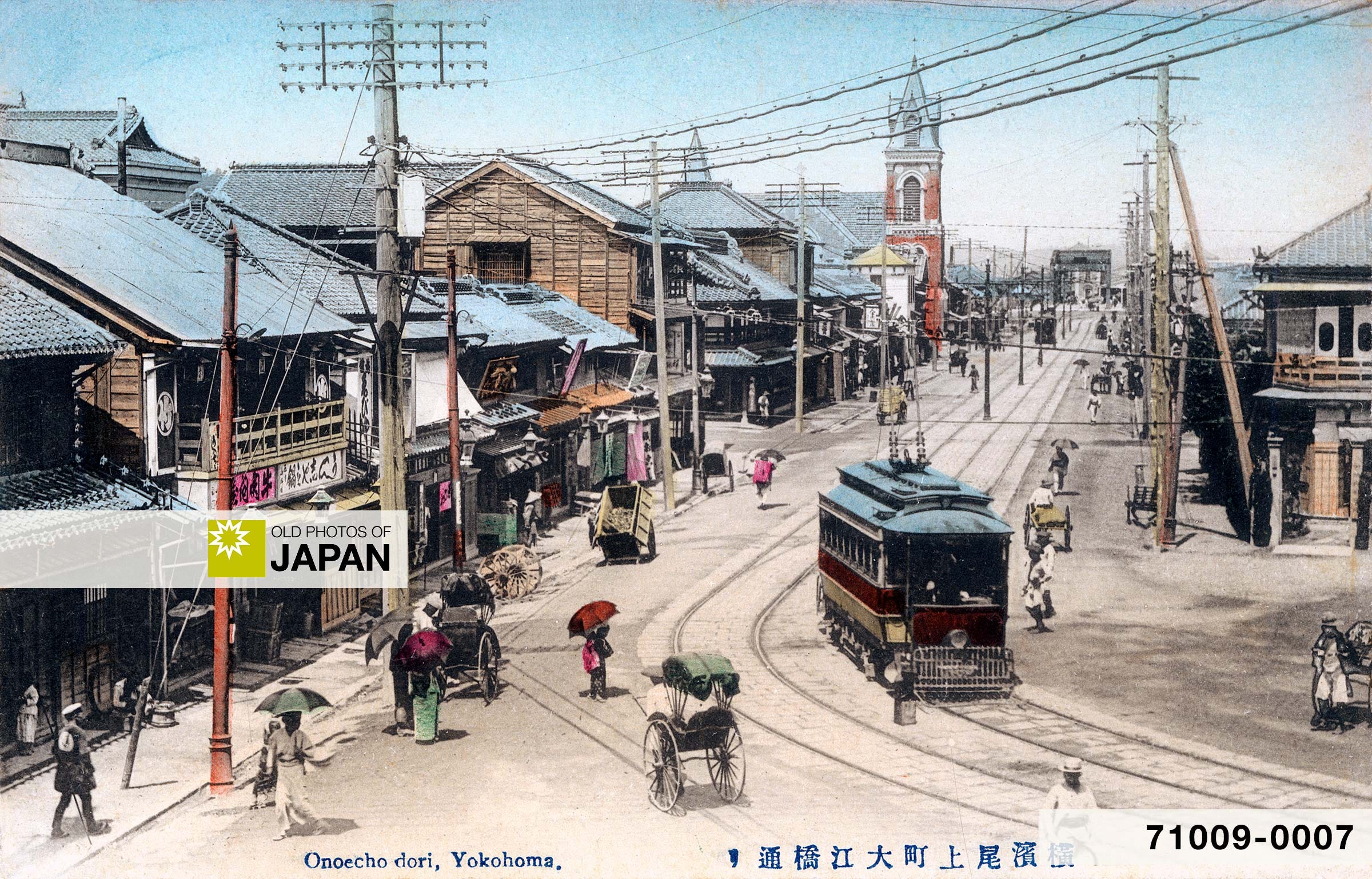

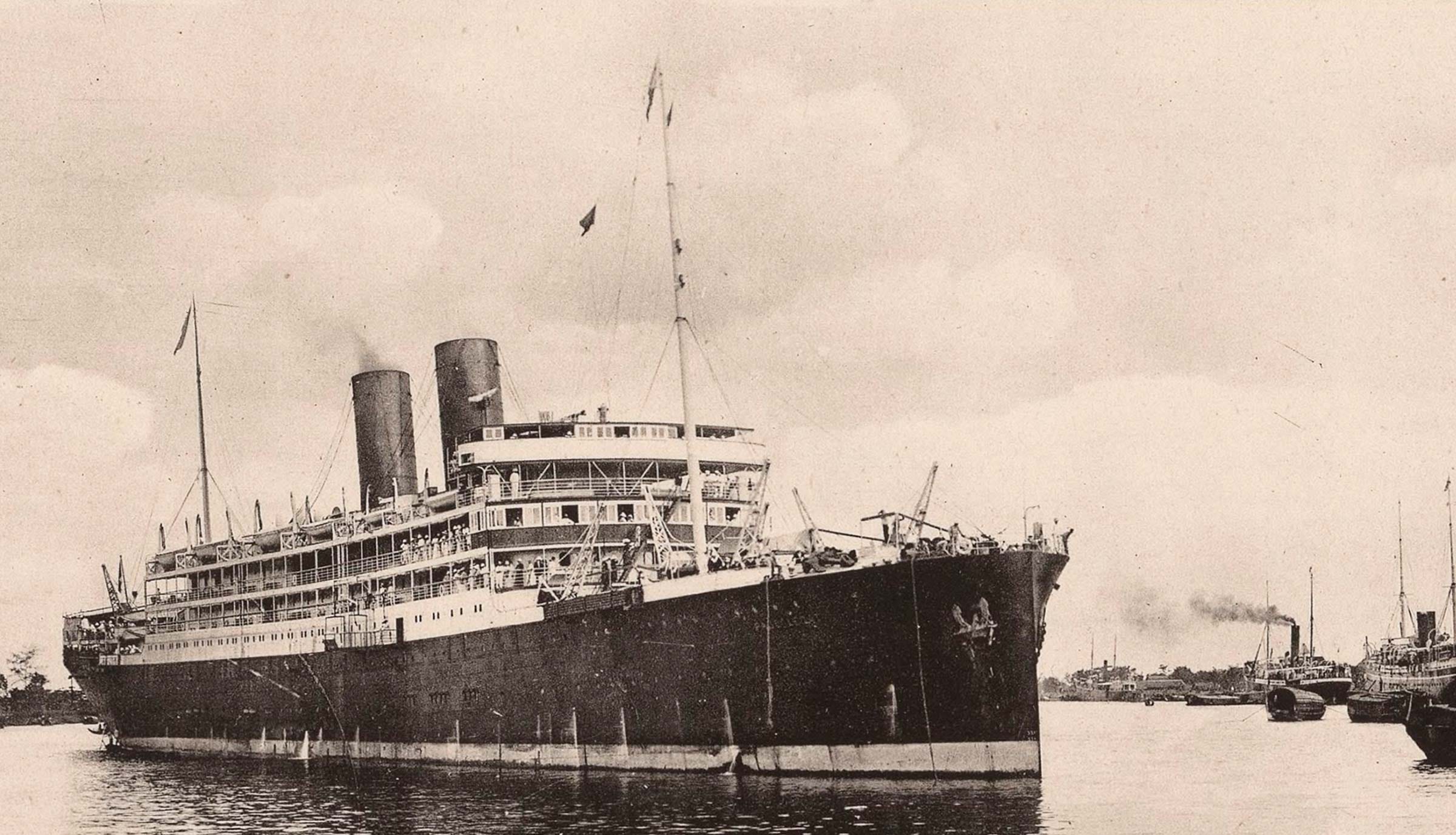

On September 1, 1923 Cozad was in Yokohama to drop off her cousin Ella Brunner at the passenger ship Empress of Australia. They arrived an hour before the ship was scheduled to sail for Vancouver. The two had spent a week vacationing in the resort town of Karuizawa at the end of Brunner’s month-long tour through Asia. Since the 1880s the town in Nagano’s cool mountains had become popular with expats for spending Japan’s hot summer months.

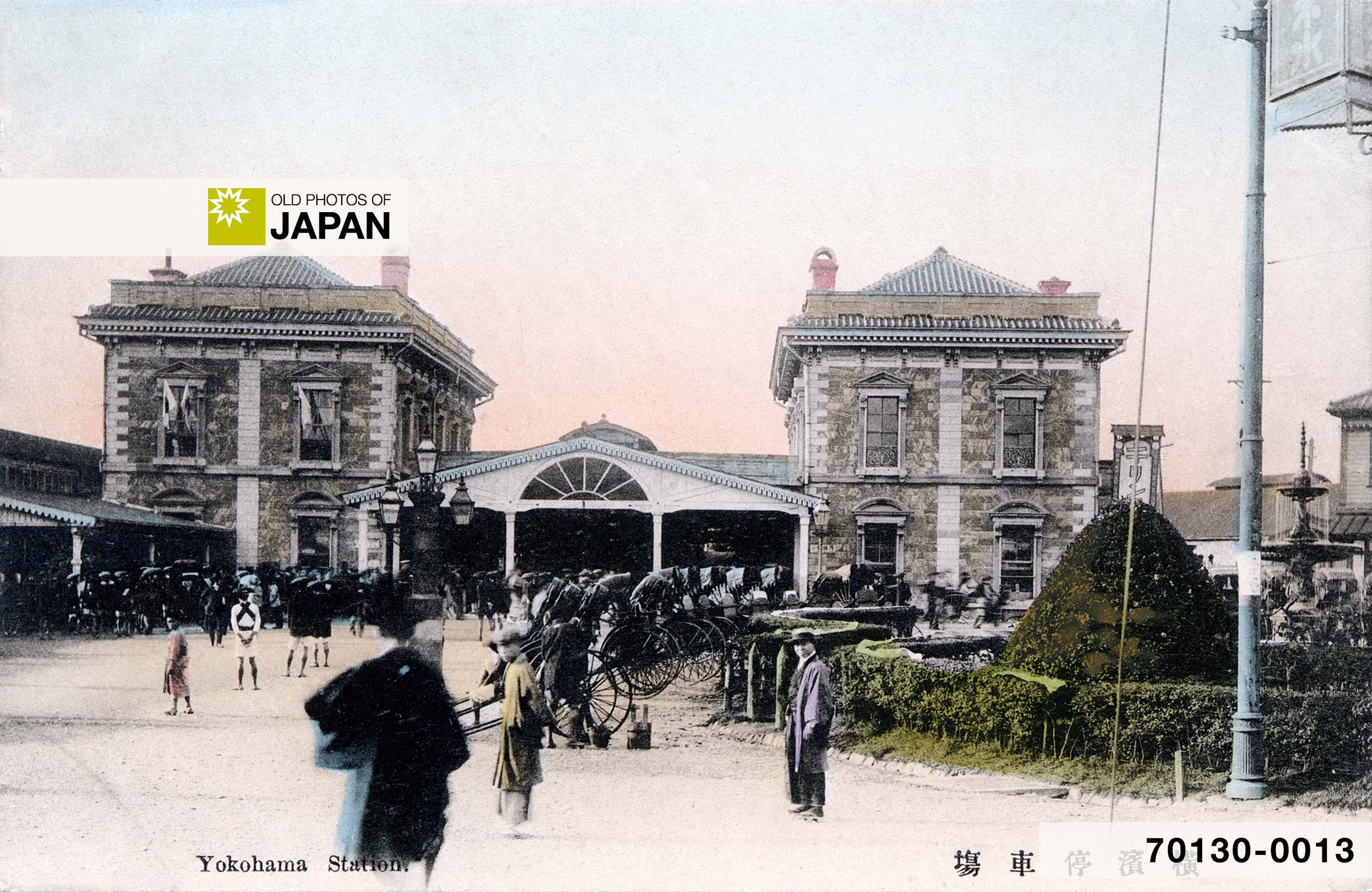

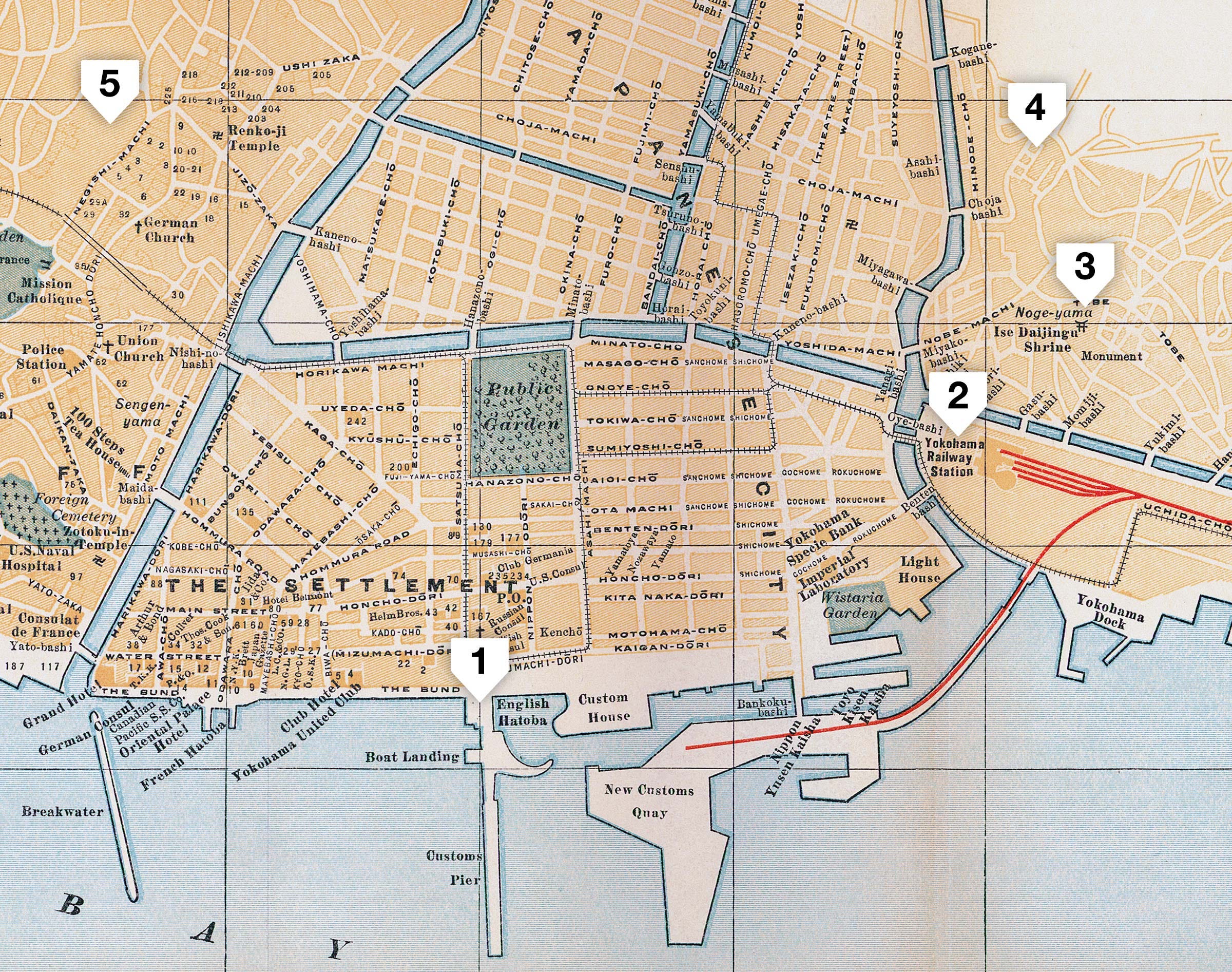

After dropping off her cousin, Cozad hurried to the station to catch the train to Kobe. At Sakuragi-cho station she boarded an electric streetcar for Yokohama Station. It is at this point that her account begins.

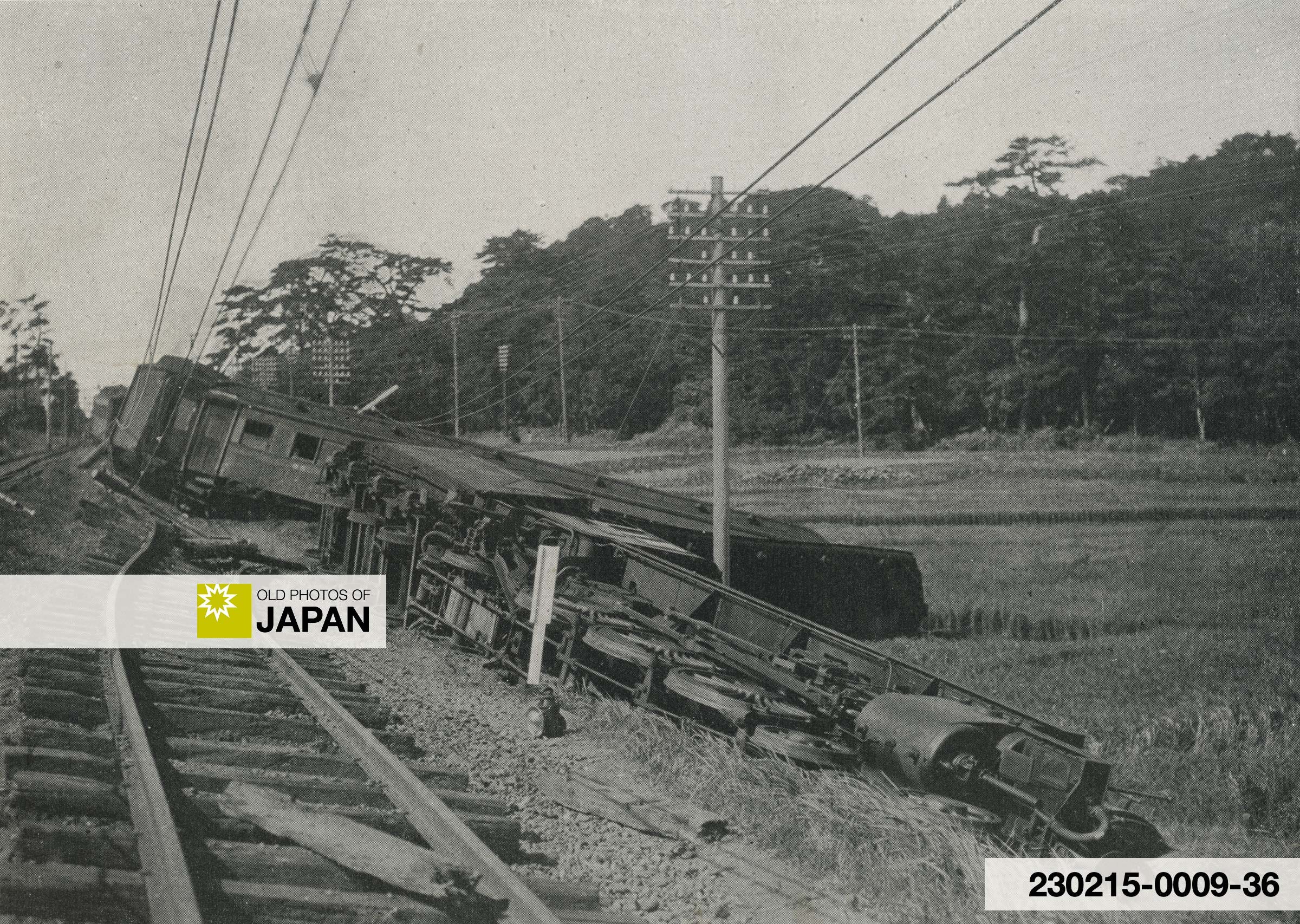

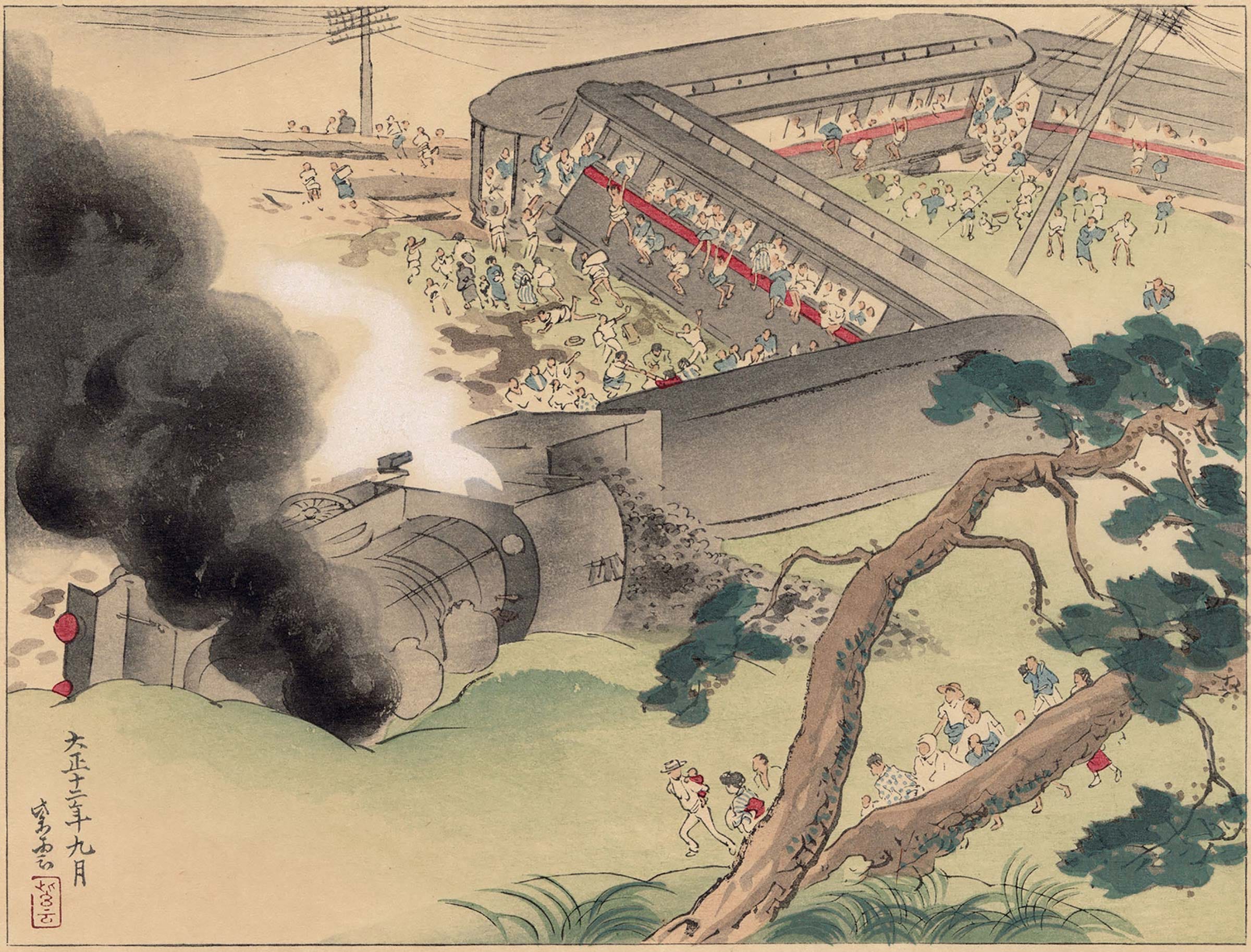

I took the electric car at Sakuragicho Station for Yokohama. We had just pulled out of the station at 11:58 A.M. when the car suddenly began to jump and knock and swing around in the strangest manner, utterly indescribable. It seemed Inevitable that the car should turn over. We crouched and ran for the door and jumped off, falling to the ground. We were on a built up sort of concrete trellis place but the concrete was broken into bits, part of it a foot lower. The car next to us was overturned.

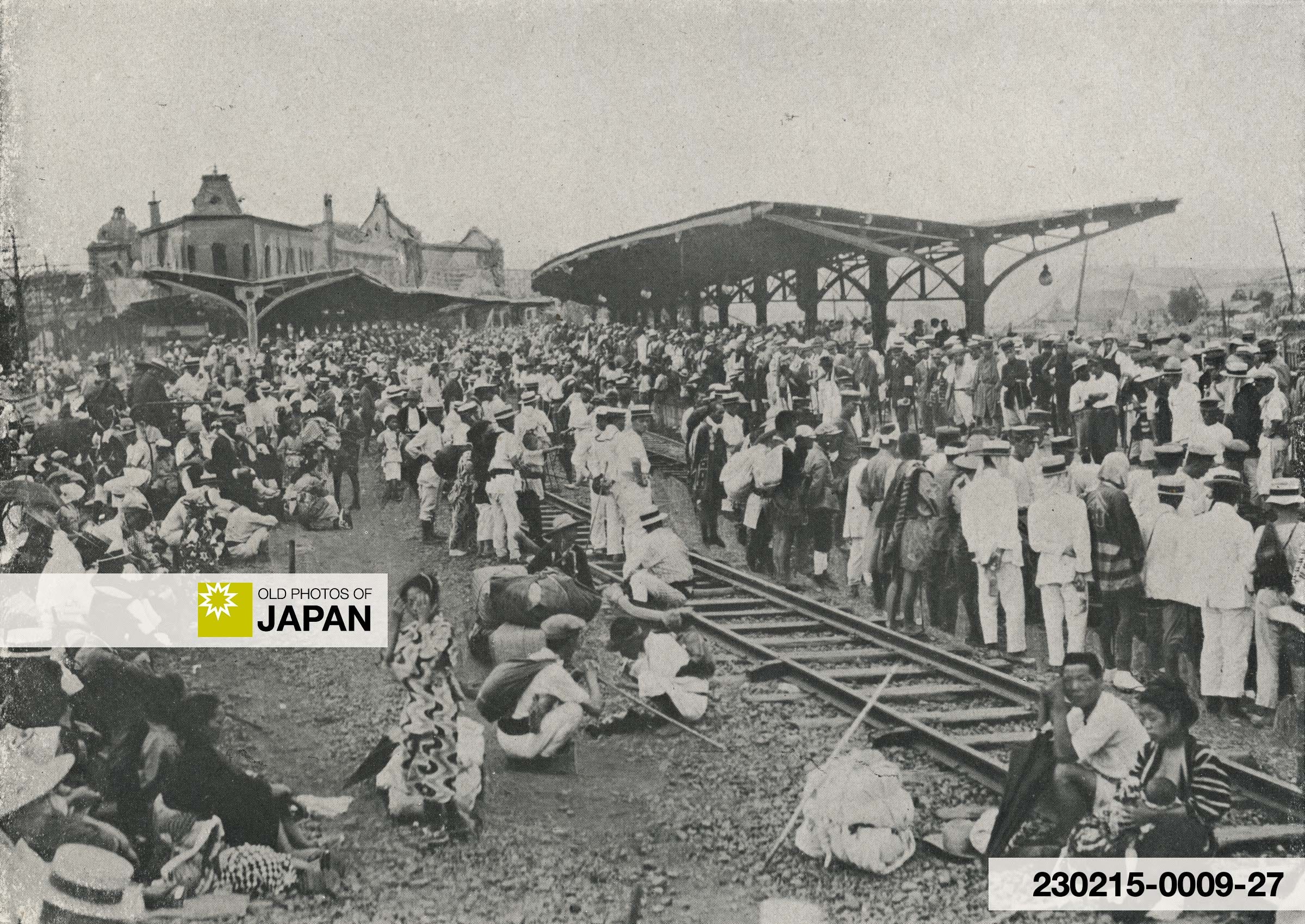

Too dazed to realize what had happened I glanced around me and not a house was standing. A yellow dust arose and a great shriek — and then a deathly silence. I cannot account for the silence. It may be I was too stunned to hear. A porter seized my bag and we stumbled back to the station, avoiding the falling wires. Many people on the crowded cars were electrocuted — a merciful death.

The station and two large buildings were still standing but ready to fall. While we waited In the large open place in front for the shaking to let up, immediately in all directions fires sprang up. A stream of humanity came pouring towards us, many of them bleeding. I did not know what to do. A man came saying he was on the bridge when the earthquake came and had lost his handbag. He thought someone had taken it and would someone please tell a policeman about it!

Gertrude Cozad, September 6th, 1923

I knelt on the ground until a policeman whistled and said “Everyone to the hills.” Not knowing Yokohama I followed the crowds over the broken tippy road, the walking being very difficult. We feared we would fall into the great long, often recurring, ugly cracks in the ground. One man had the experience of the earth opening where he was standing, and he fell in up to his waist.

I saw a young man of twenty walking beside me and said, “Are you alone?”

“Yes.”

“Won’t you stay with me today?”

“Gladly”

“What is your name?”

“Hayashi Shotaro.”

So we began our sad journey together and never a knight had more faithful [a] squire. If it were not for him I think you would never have had the account of this day from me. He proved to be a Korean youth with no relatives.

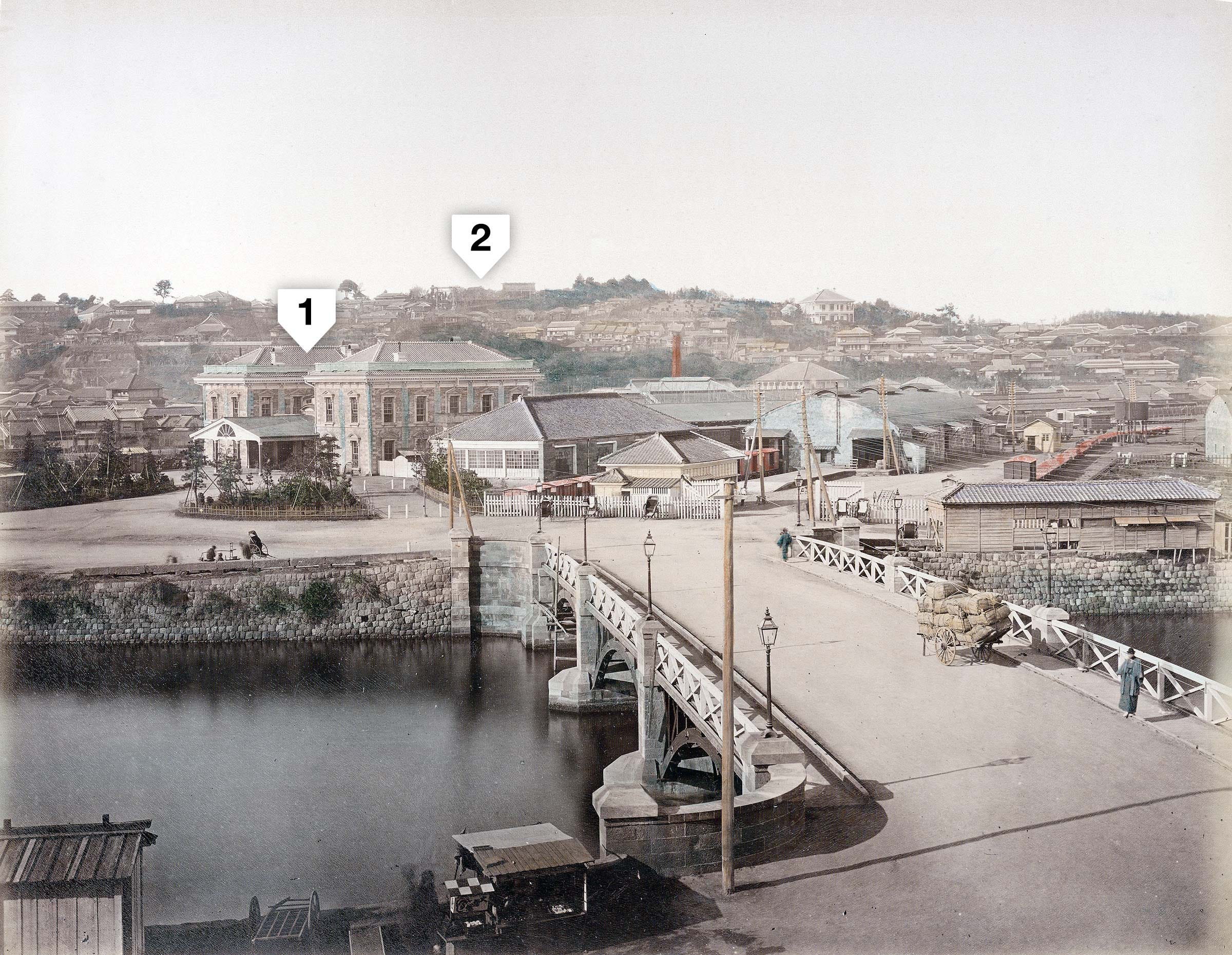

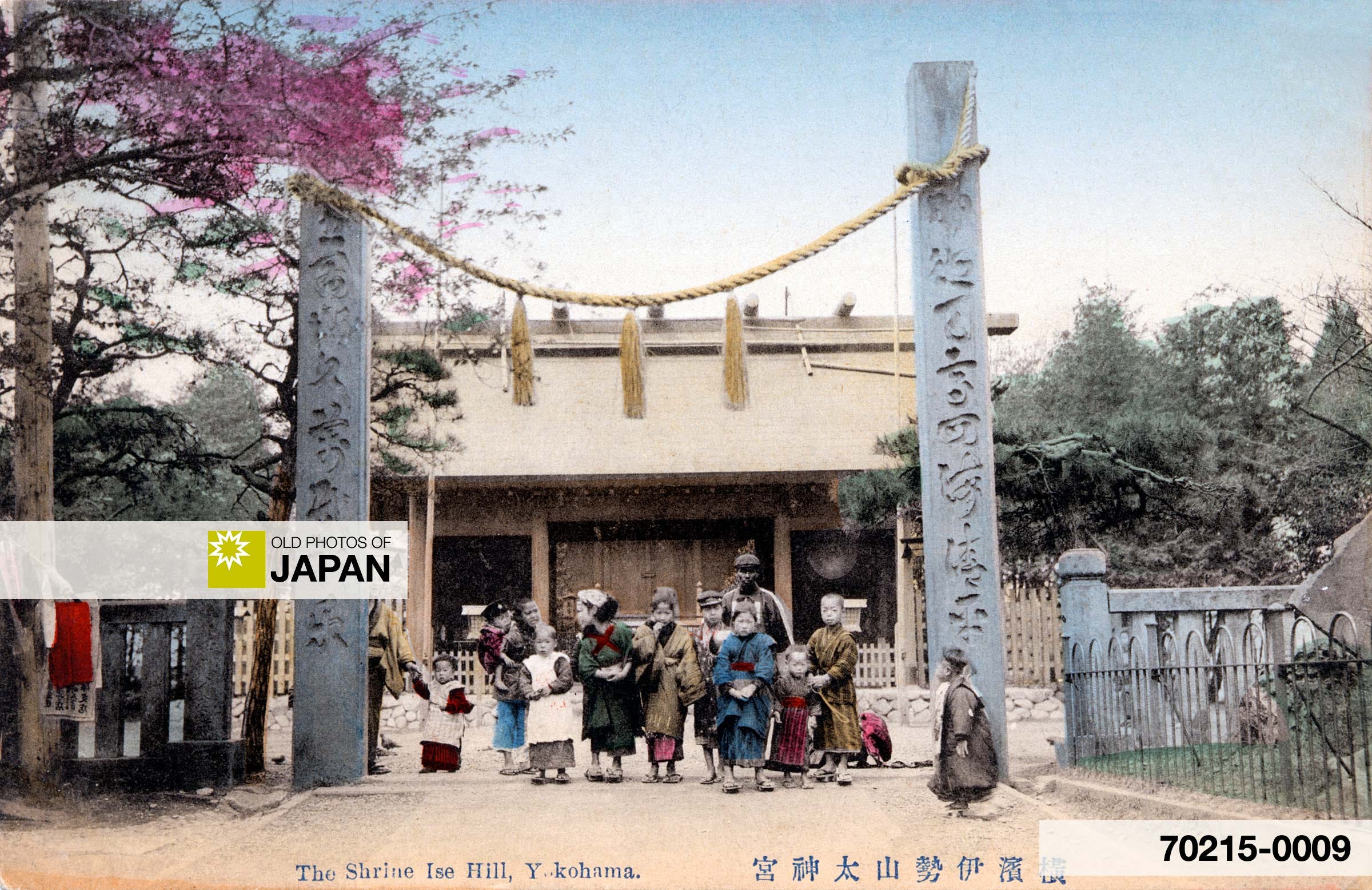

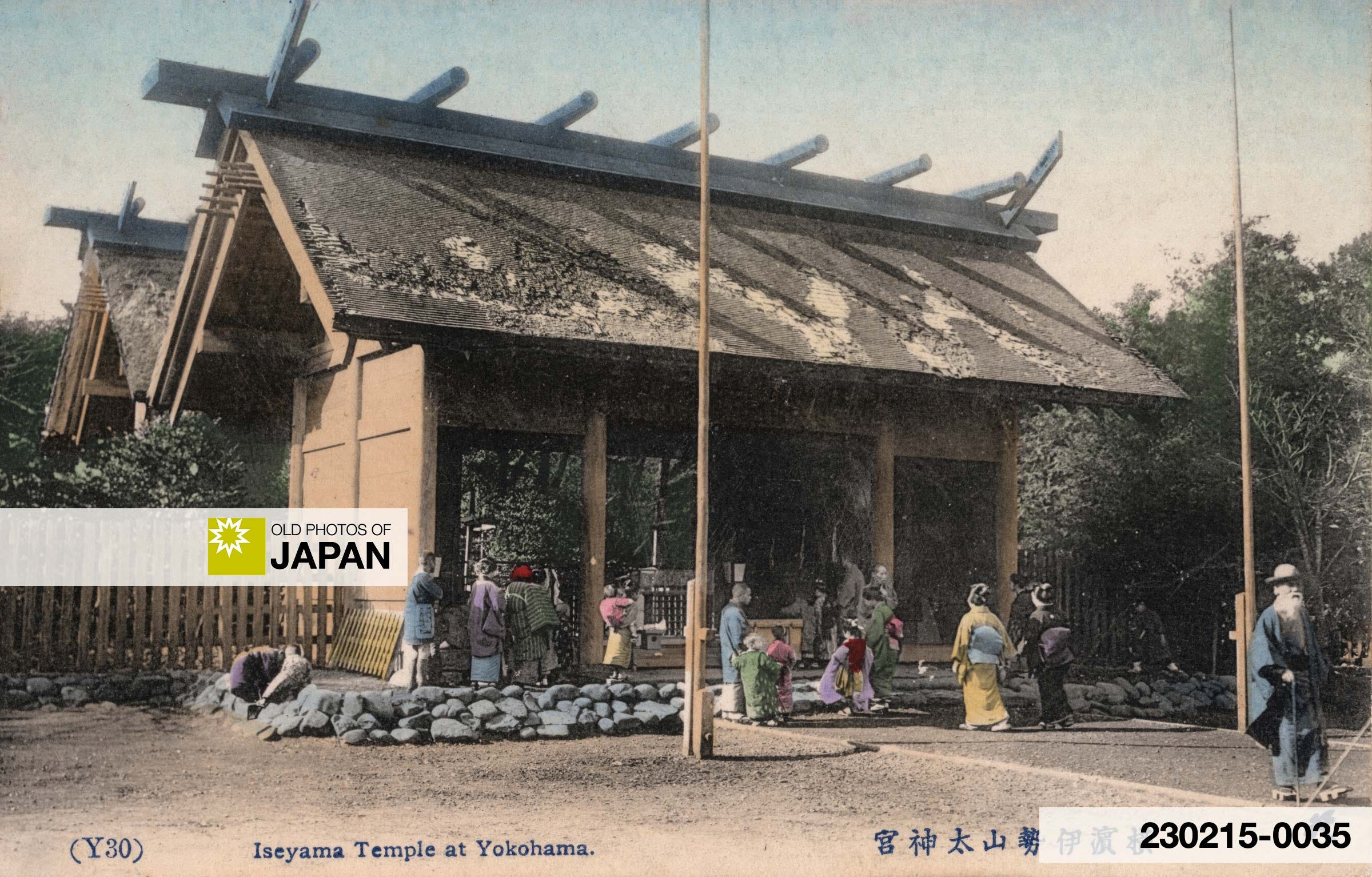

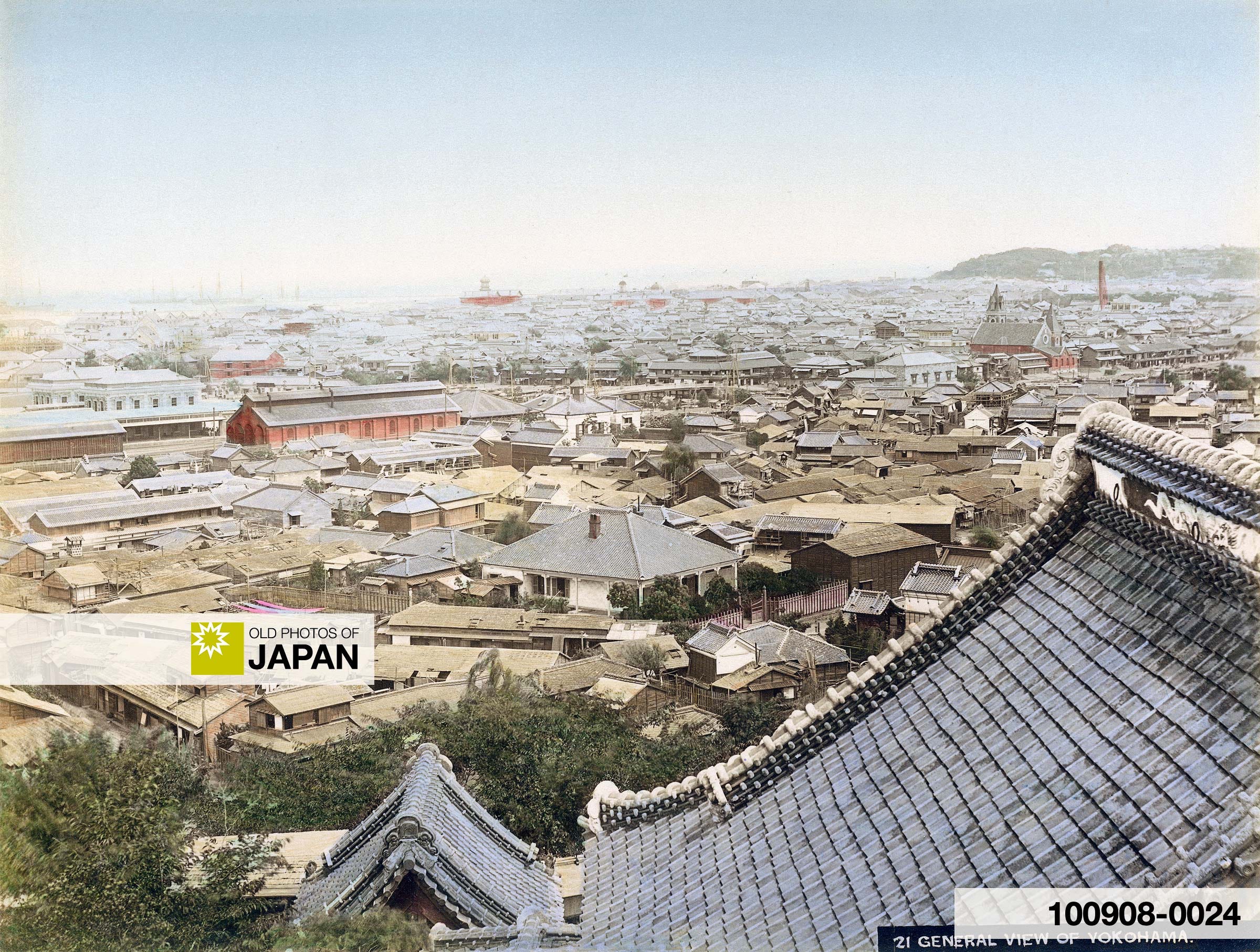

We went up Noge-saka [Nogeyama] till we came to a shrine of Daijingu on a high hill. The shrine itself was strangely intact, sitting there calmly as if it always had and always would, while the larger buildings around it had fallen. You can Imagine how the safety of the shrine had impressed the frightened people and how many fervent prayers were offered there. The people began to pour up there from every direction till I should guess there were more than a thousand. I thought we were quite secure and we stayed there several hours.

Gertrude Cozad, September 6th, 1923

I became so interested In the various groups. The rich and the poor, the calm and the frightened were there. One woman sat there erect and smiling with her six children sitting in a row, proper and quiet as If they were in a Sunday School. How good the young men were to their mothers! One man said he was connected with the Y.M.C.A. He brought his mother, his wife and baby and his sister to safety. They had nothing but one egg each which he had picked up as he passed a store, leaving his card and expecting to pay later. One man toiling up with a kerosene can full of [mizuame] (a sweet mixture of the consistency of honey). He leaned over as he toiled up the hill and the heat of the day and the many fires melted the ame, so when he put down the can, from his hair to his waist he was one shiny mass of sweetness.

The wounded were brought up on people’s backs. An old woman came leading a stalwart young man who stumbled along and she supported him as best as she could. My boy went off to reconnoitre and came back with a girl of twenty on his back and mother tottering after. We made them as comfortable as we could on a piece of matting.

The boy went and came back again saying he did not like the look of things. The fire was getting pretty near on two sides and the wind was blowing a gale. I went off to look and did not like it either. I saw two official-looking men and said, “It looks a bit serious, does it not?” “Yes,” they said, “but what are you going to do about it? We can’t get away and what place could be safer?” I went back to my boy and said, “Let’s get out of here.”

“But how can we leave these women? They will be terrified.”

My heart clung to those persons we had been watching — the little girl of eight who had been praying steadily for two hours, the old blind woman whose face was peaceful but whose lips never ceased to move in prayer, the frail white-haired men and women who clung to each other with such a look of despair, the mother, the son, his little girl and wife lying there with her baby a few days old. Still I could not help them and many people were not undertaking a difficult and hazardous way of escape.

Gertrude Cozad, September 6th, 1923

We stole away from the prostrate friends, hoping they would not see us go. Our objective was a villa on high land across a deep valley with precipitous sides all broken and crumbled, over some houses and up a hill so steep l could never have done it without help. I begged my boy to throw away my baggage, but he clung to it, and would go on and place it, find the best footing and then came back and get me. In going down he would place his foot and have me step on it, and in going up he would pull and push.

We would reach the top at last. There were two villas, a shallow pond, and an open space and trees. The made ground was broken badly and at every shake (there were 150 of them that day and 500 in all) I feared the place might slide into the valley.

After resting a while we moved on into a valley, but I could not stand it to be there where I could not see anything, so we went up another wooded hill to a pleasant wooded place with many people sitting around and a cow lying down and chewing her cud. Here we could see the approach of the fires, so we said, “Let us find our way into the country if possible.” We climbed another steep hill under fallen trees and over the debris of houses, with the other people behind always calling, “Hurry, hurry, we shall all be burned alive!” And so we went on till we came to the city reservoir, the highest place in Yokohama. The whole city was burned up to it on one side clear over to the Bluff, which was burning fiercely.

We sank down on the sand they have in the brick enclosure for filtering purposes, and felt we were as safe as we could be anywhere and watched the four places we had been in one after another burn and burn.

The loss of life at the shrine was terrible. There was no way of egress but the one we had negotiated with so much difficulty. As we crossed the narrow neck of the valley the flames were within I should say three hundred feet [91 meters], and the heat was intense. Had we waited ten minutes there would have been a panic, the strong pushing the weak in their frenzied efforts to get away. Many were tramped under foot, many more were dropped by the wayside to be burned alive. It was heartrending to watch the cruel beautiful flames, and to think of the many who had been interesting to us who could not get away.

Gertrude Cozad, September 6th, 1923

This is where Cozad ends her initial report. From her extended report deposited at the Boston Athenæum we know what happened next.12

Some eighteen Japanese survivors reached their spot and built a shelter from corrugated iron. Here the small group spent the afternoon and night.

Against the glare of the burning city there was a constant procession of dark silhouettes, calling the names of those from whom they had become separated. . . . One fine appearing young man was brought there, wounded and scorched. He had been dragged out from the debris and his wounds bound up, and then left where he fully expected to be burned. His father found him and brought him to our camp. All the afternoon I thought he was dying, but . . . rejoiced to see him open his eyes, and when I left he was sitting up.

Gertrude Cozad

As Cozad and Hayashi woke the following morning they heard gunshots, screams and the shouts of vigilantes. Hundreds of men were hunting Koreans. False rumors were spread that Koreans were looting, setting fires, and poisoning wells. Many Japanese officials—even the police and army—joined in the killing. Hayashi was in mortal danger, but their small group’s courage, trust and solidarity saved him.

[They] knew he was a Korean but were kind to him and tied a red cloth on his arm, which signified that he was Japanese. My boy lay with his face in the sand, beside me, all through that time.

Gertrude Cozad

On September 3, after the screams and gunshots of the previous two days had subsided, Cozad and Hayashi climbed down from the reservoir. They wanted to get to the harbor to see if they could find a ship to take them away. When they passed the Daijingū shrine Cozad looked up. Hayashi told her, “Don’t get up there. It is too terrible,” and they pushed on.

Hayashi’s red armband protected him and they managed to reach the pier without any interference. But the place was an utter shambles.

They found a launch that took them to the French liner André Lebon. But as they reached the ship the crew of the launch demanded money. The sailors of the French vessel were furious and threw one of the crew members back into the launch as he was trying to board the ship. They blocked Hayashi as well.

Cozad was worried. The launch crew had given Hayashi the side-eye as they discussed the killings of Koreans. She stood on the gangway and shouted, “That boy saved my life and I will go back on the launch unless you take him on too.” To their great relief he was allowed on board.

Late that afternoon, Cozad was taken to an American liner that had just arrived from Shanghai. It took her back to Kobe where she arrived on the fourth. On the ship she tried to reach her cousin on the Empress of Australia by wireless but was unsuccessful. Brunner survived, but it is unknown when they found out that the other was safe and sound.

Hayashi remained on the André Lebon and reached Kobe two days after Cozad. He spent hours wandering through the city trying to discover where she lived. When he finally found her name on her gate he leaned against it and burst into tears. Cozad took him in, took care of him, and later entrusted him to the care of her sister who lived in Seoul. She promised to support his education.

He is a fine looking young man, with good features, rather short, and has the finest, white teeth I ever saw. There is something most winning about his personality.

Gertrude Cozad

Numbers

The magnitude 7.9 quake devastated the Kantō area—Yokohama was completely consumed by fires, half of Tokyo was. The grim charred wasteland was strewn with piles of blackened and distorted corpses. Between 100,000 and 140,000 people lost their lives, the great majority suffocated or burned to death. Nearly 2 million were homeless.

An estimated 6,000 Koreans were killed by vigilantes, as were hundreds of people mistaken as Korean, and a number of socialists, communists, anarchists, and other dissidents.

The economic cost of the damage amounted to about four times Japan’s national budget for 1923.13

Notes

The one hundred and thirteenth Annual Report of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Boston: Congregational House, 155.

The school was located at 59 Nakayamate-dori (中山手通59番), its Japanese name was Kōbe Joshi Shingakkō (神戸女子神学校). For a brief history, see 西宮聖和キャンパスの由来 (pdf).

Weissenbacher, Manfred (2009). Sources of Power: How Energy Forges Human History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 243.

Cozad-Bates House Interpretive Center. Retrieved on 2023-06-02.

Catalogue of officers, graduates and students of Western Reserve College and Adelbert College, 1826-1916. Cleveland, Ohio: The Western Reserve University Press, 36. Retrieved on 2023-06-03.

Bays, Daniel H. The Foreign Missionary Movement in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. The University of Kansas, National Humanities Center. Retrieved on 2023-06-03.

ibid.

Seat, Karen (2003). Mission Schools and Education for Women in Handbook of Christianity in Japan. Brill, 321.

Mullins, Mark R. (1998). Christianity Made in Japan: A Study of Indigenous Movements. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 17.

Klein Faust, Allen (1909). Christianity as a Social Factor in Modern Japan. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Steinman & Foltz, 33.

There were also an unknown number of private schools managed by Japanese Christians.

Patessio, Mara (2011). Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, 75.

Lepach, Bernd, Meiji Protraits: Cozad, Gertrude. Retrieved on 2023-05-26.

Account of the experiences of Miss Gertrude Cozad in the earthquake at Yokohama, Japan September 1 to September 4 1923. Boston Athenæum Special Collections, .L366.

Schencking, J. Charles (2013). The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Retrieved on 2023-06-04.

Schencking, J. Charles (2013). The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923: The Aftermath: Rumors, Anarchy, and Murder amidst the Ruins. Retrieved on 2023-06-04.

Denawa, Mai (2005). The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Brown University Library Center for Digital Scholarship. Retrieved on 2023-06-04.

Ryang, Sonia (2007). The Tongue That Divided Life and Death. The 1923 Tokyo Earthquake and the Massacre of Koreans. The Asia Pacific Journal, Volume 5, Issue 9. Retrieved on 2023-06-04.

Having experienced the March 11, 2011 disaster in Tokyo, I’m very grateful after reading this that Tokyo wasn’t consumed by flames. It took me over 3 hours to walk home but the crowd of fellow travelers was friendly and there seemed to be no danger of being massacred like the Koreans in 1923. We live under the threat of earthquakes happening any moment, but still we live here hoping they won’t happen again.