Yokohama 1860s • The Fruits of Fire

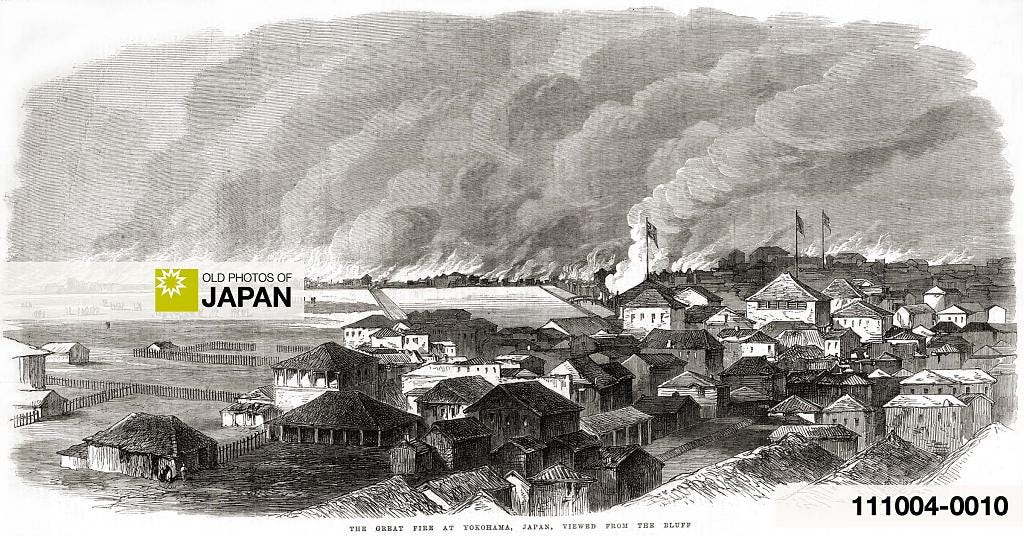

On November 26, 1866, a horrifying fire devastated Yokohama. The fire has been largely forgotten, but it gave birth to the urban plan that still defines downtown Yokohama today.

Read this article on the site | Comment on this article.

In Japanese, the fire is known as the Great Keiō Fire (慶応大火, Keiō Taika). It was also called the Pork Shop Fire (豚屋家事, Butaya Kaji), as it started at a pork restaurant in the Japanese town.

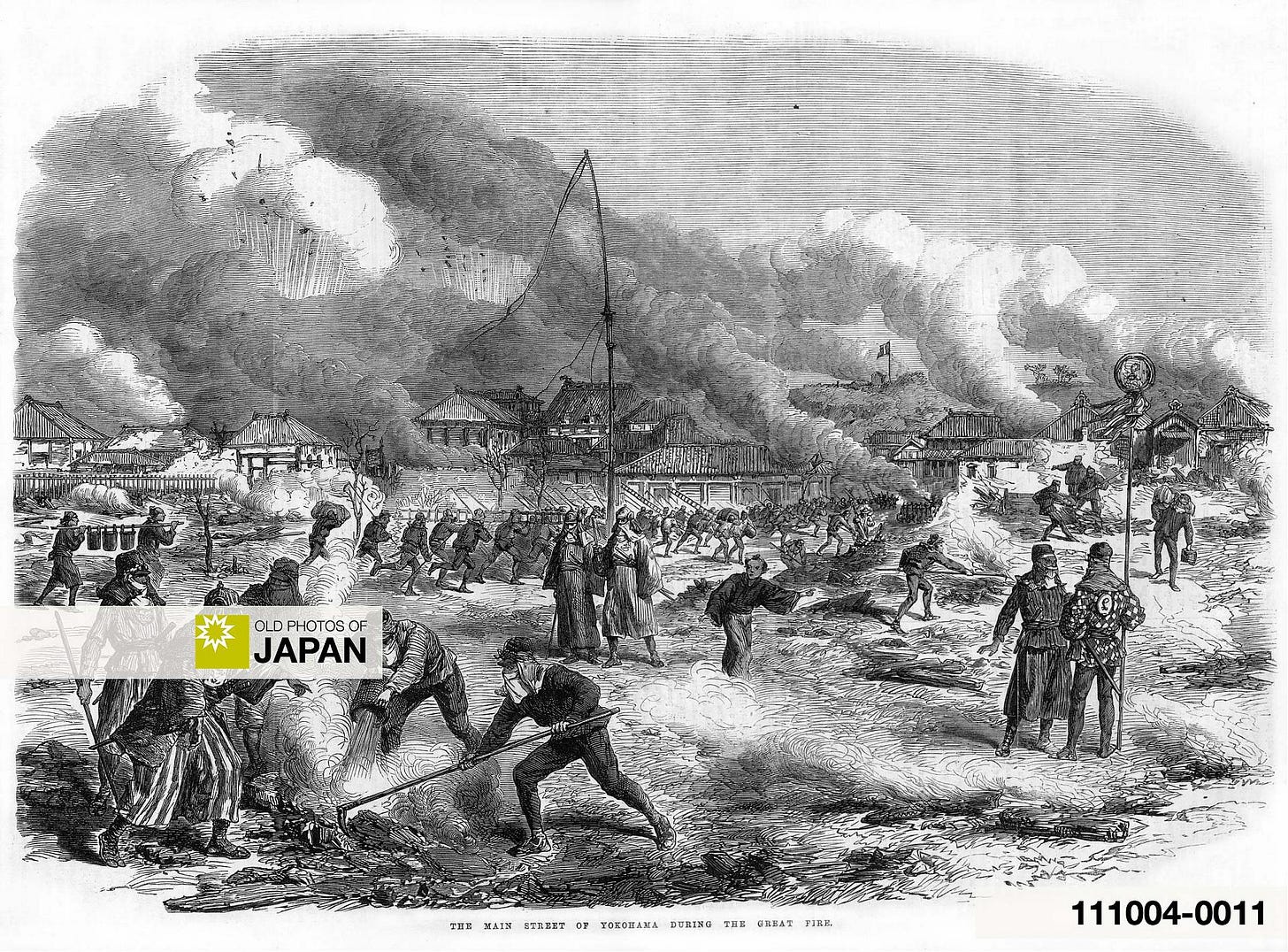

The fire started just before nine in the morning and then quickly spread to the foreign settlement. It continued to burn all day long, until late at night.

Fire fighters were absolutely helpless, and troops encamped in the settlement resorted to blowing up several buildings to stop the fire. It generally had the opposite effect.

The fire was especially devastating to the brothel district of Miyozaki, known to the foreign inhabitants as Yoshiwara. It was completely leveled.

Sadly, the people who worked here had no way out. The fire approached through the only entrance way, and the quarter was surrounded by a moat to prevent the women from escaping.

Many tried to escape by laying make-shift bridges over the moat. But in the panic and because of their unwieldy kimono, countless women fell into the water and drowned. Of the 400 people that perished in the fire, the majority were prostitutes.

Several month after the fire, Dutch trading company Carst, Lels & Co. published a notice about the fire in Dutch daily Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. Three of their buildings were destroyed, the company explained. But thankfully they were all insured.

According to the company, the insured loss to Yokohama came to 2 million dollars, an enormous amount at the time. The report ended on a dark note: “To determine the total loss, however, a large sum must be added for uninsured buildings and goods.”1

The enormous loss is not surprising. At the time, Yokohama accounted for approximately 80% of Japan’s foreign trade.2

The fire led to the 3rd Land Treaty between the inhabitants and the Shogunate government. British engineer Richard Henry Brunton (1841-1901) was employed to create a fireproof urban plan for Yokohama.

Amongst other things, Brunton suggested to create Yokohama Park, and a 36-meter wide avenue between the Japanese and foreign settlements, to serve as fire breaks. That street still exists, and is now known as Nihon Ōdori (日本大通り).

The park was completed in 1876. Today, it is the location of Yokohama Stadium. When you search carefully, you can find a stone lantern in the park that functions as a monument to the red light district that was once located here.

There is also a bust of Brunton. He tirelessly watches Nihon Ōdori, and the urban framework that he designed.

Another element of the land treaty was the construction of the Negishi Race Course (根岸競馬場). It was built shortly after the fire and became one of the most popular attractions of the area.

Even Emperor Meiji visited some fourteen times.3 In 1943 (Showa 18), however, the course became the property of the Imperial Armed Forces and horses never raced here again.

We have no photographs of the fire or its aftermath. The fire actually damaged the studio and many negatives of famed photographer Felice Beato (1832–1909), who had settled in Yokohama three years earlier.4

But we do have a detailed report of the fire by Scottish journalist John Reddie Black (1826–1880). Within two days, he published it in The Daily Japan Herald. At the time, he didn’t yet know how bad the death toll really was.5

It is with feelings of profound gratitude that we find ourselves able to sit down unscathed, to record one of the most awful catastrophes it has been our lot to witness. The 26th November 1866 will ever be remembered in Yokohama as one of the blackest days in its annals, for the conflagration which consumed nearly two-thirds of the native settlement and one-sixth of the foreign.

The morning broke on one of the brightest days of the season, but the wind which had been blowing strongly from the south during the night seemed increasing in power, and, blowing over the bay towards Kanagawa raised the spray in perfect clouds.

At a little before nine in the morning, the fire bell rung out its fierce alarm, and all rushed to the scene, which was found to be the street heading from Benten-dori to [Yoshiwara]. In a few minutes however, flames were seen issuing in various quarters simultaneously. [Ota-machi] broke out at several points: the new American Consular building, at the distance of fully a quarter a mile, showing flames through the roof at the same moment.

The flames worked up against the wind from the locality in which the fire originated, and in half an hour the whole of [Yoshiwara] was destroyed. With the exception of one or two fire-proof godowns [warehouse] and the temple at the end, not a single stick was standing to mark the boundaries of dwellings. Unhappily, we have to record that here was a terrible loss of life, if we may believe the reports of the Japanese themselves, who state that thirty five bodies have been found.

[Yoshiwara], being quite surrounded by water, and there being only one narrow bridge; which led in to the street that was already in flames, became a cul de sac, from which the only retreat was by improvised bridges of boards, or by punts which were brought in to use with all the celerity possible; but the flames were so rapid in their work of desolation, that many fled from them only to meet death in another element.

The Daily Japan Herald, November 28th, 1866

We hear that in several parts of the native town persons were burnt or crushed to death. In [Ota-machi], the effects of thoughtlessness and disorganisation were painfully apparent.

All along the street, the people were getting their little movables out, to fly with them to the mumechi (the newly filled in ground) or some other place of safety, but towards the end near the foreign settlement, several shops had filled up the street with their goods and chattels, thus making a perfect barricade, and here was an obstruction, that even we who were unencumbered found great difficulty in overcoming; whilst those who were carrying loads were driven to desperation in their efforts to pass, and many women and children were very much hurt.

Meanwhile the fire spread towards, and in, the foreign settlement. The New American Consulate was now literally level with the ground, and reports flew around, that No. 1, the residence, offices, and godowns of Messrs. Jardine, Matheson & Co., had caught. In another few seconds it reached the whole settlement that the private residence on No. 2—Messrs. Walsh, Hall & Co. was on fire.

Simultaneously with this, the whole range of the old Consular buildings—the French, Prussian, American and English, in which latter several gentlemen of the English Legation and Consulate were residing—were swept off like so much tinder.

The wind increased almost to a typhoon: the sparks communicated with the old Japanese Custom house, and in almost as short a time as it takes to pen this tale of desolation, it was a thing of the past.Now arrived on the ground a party of soldiers, who commenced to knock down the portion of the new Bonded warehouse buildings that had any exposed wood; but the debris caught as it fell on the ground, and the first building was in flames. Mr. Seare, in his correct perception of the impending danger, directly the alarm of fire was given, caused all the window shutters of Bonded warehouse A (which were coppered on the outside) to be closed, and the crevices filled up with mud—but it was of no avail; almost before it could be finished, the roof had become ignited, and it was, if a less speedy, an equally certain prey to the raging flames.

Happily the wind continued to blow steadily in the same direction as when the fire broke out—and hopes were entertained that the direct line the fire had taken, would be that in which it would exhaust itself on reaching the sea shore.

Already the native town had found a boundary beyond which it did not pass, and all was level but smouldering, when a momentary shift of wind sent a spark in at the single unclosed shutter of the foreign godown nearest to the native town, on No. 89 and immediately another strip of buildings caught, and in a most wonderfully short space of time, the whole blocks No. 70, No. 50, Nos. 41 to 43 and 1 and 2 were all ablaze. Now serious apprehensions began to be felt for the settlement; as, should the wind continue high and shift to the eastward, nothing seemed likely to save it.

The Daily Japan Herald, November 28th, 1866

The fire engines were brought out the instant the alarm of fire was given; but alas, for the efficiency of the Yokohama Fire Brigade, there was not the slightest organization; and some of the engines were entirely useless—having got out of order, probably from disuse. It was difficult also, to procure a sufficient and continuous supply of water for some of those that were well manned and in order, so that at length there seemed to be an almost entire absence of effort to make them available.

About 11 o’clock the wind shifted a little more easterly, and quickly laid hold of the houses and godowns in the new direction. No. 71 and part of No. 72 in the Main Street—and Nos. 51, 52 and 53 were speedily attacked—proceeding in the same direction, Nos. 44 and 49—Nos. 21 to 28 and 3 to 8 became sharers in the general woe.

About 11 o’clock, much apprehension was felt, in consequence of its being reported that there were three cannons, loaded with ball, on No. 51—and that the balls could not be drawn. This difficulty was got over by the military, who, either removed the guns to a place of safety, or otherwise made them secure. Shortly after, there was an alarm spread, by the report that one of the godowns that was about catching, had a quantity of gunpowder in it. The proprietor allayed any apprehension on that score, by contradicting the report.

Up to this time, the Naval and Military had worked well, as to do them justice, all the officers and some few of the men continued to do throughout the day. Colonel Knox, of H. M.‘s 2nd 9th, was in all directions trying to direct the efforts of his men—and Admiral King and Captain Jones from the Princess Royal, with Captains Courtenay, Stevens and Waddilove, with detachments from H. M. S. Scylla, Perseus and Adventure, used every possible exertion.

Lieut. Bond with his Sappers worked with the utmost zeal throughout the whole day; but all seemed hopeless; there was no impression made upon the general conflagration; and in spite of everything that the proprietors and their employees could do—in spite of the willing and hearty co-operation of their friends and of all who had hands to help, and the daring of the soldiers and sailors, the fire had it all its own way.

At length, it was determined to blow up a number of buildings across the line the flames seemed likely to take, and a commencement was made in the house of Mr. Van der Tak [agent of the Netherlands Trading Company]. A protest was made by the owner, and, it is said, by some of the Consuls; but the Admiral, deeming it the only thing that could be done to cut off the communication, persisted.

Whether the step was judicious we will not pretend to say, for the débris of the house caught and burnt to ashes. The adjoining house, the Club, however, was not consumed, although it caught fire once or twice; but it was terribly shaken by the explosions, and much damage was done to it. The exertions of Mr. Smith and his staff succeeded in extinguishing every ignition that occurred.

In most instances the houses blown down subsequently ignited and became an easy prey to the flames; and the last—a new fire-proof godown belonging to Messrs. Textor & Co.—was only saved from combustion by a miracle, —as the stone work having been all shaken down—left the woodwork quite exposed, and at nightfall, the premises exactly opposite—No. 8—having been entirely destroyed, the wind changed, and a perfect rain of sparks fell among the rubbish. How it failed to ignite, was simply miraculous—and if it had caught, we do not know where the mischief would have stopped. As it was, the buildings of of which it formed a part, escaped through the resistance the corresponding fireproof walls, on the opposite side, offered to the fire—so that, with the exception of the sparks before-mentioned, the fire did not reach that limit.

On the Bund the first building that escaped was the French Hospital. It was proposed to blow this up—but the Commissaire objected so strenuously, that the idea was, as it happened, fortunately abandoned. The house of Mr. Davies (Adamson & Co.) on No. 28 was in great peril. Some of the other buildings on the lot were destroyed. At one time it seemed that Nos. 54 to 68 in the Main Street must inevitably go—but happily, although all received some damage, it was of no very great extent. To save them, however, their owners had to use almost incredible exertions, and but for the assistance of a party of men from one of the merchant ships we do not think that No. 58 could have been saved.

The Daily Japan Herald, November 28th, 1866

Black specifically mentions the heroic behavior of the Japanese and Chinese. Especially the servants assisting their employers. Even though they were worried about their own homes, family and friends.

But he had few good words for the British sailors and troops. A sentiment repeated by others in private letters.

We have said, that up to about 11 o’clock the men belonging to the services worked well. By that time, however, so many had found the means of obtaining drink, that they became, with a few honourable and fine exceptions, almost uncontrollable. It was impossible to keep them immediately under the eyes of their officers, and the moment they were out of reach, their worst passions were quickly and deplorably exhibited.

It was most humiliating to see fine fellows, in whom ordinarily their country has such pride, so completely lost as on this memorable occasion, for we never saw men so utterly and helplessly drunk as many of those were, on whom so much dependence was placed for help. One gentleman whose godowns were on fire, went into his house adjoining them, and in the dining room found several who had been sent to assist in removing some of the things—helping themselves to wine with such determination, that he had to draw his revolver to drive them out.

Many of the men went in only for plunder, and we heard one say to a sentinel, who was true to his duty—“Now—you look here—You may as well shut your eyes a bit— and we can all divide afterwards.” We also heard one man ask his comrade if he knew which were the best houses in the place; —a question asked in a way that revealed plainly the meaning of the questioner.

The Daily Japan Herald, November 28th, 1866

Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. Haarlem, February 5, 1867.

History of City Planning in the City of Yokohama. City Planning Division, Planning Department, Housing & Architecture Bureau, City of Yokohama. Retrieved on 2022-03-11.

Nagashima, Nobuhiro (1998). Linhart, Sepp (ed.). The Culture of Japan as seen Through Its Leisure. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 353.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Photography in Japan. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 94–95.

The Daily Japan Herald, No. 952. November 28th, 1866.