Tokyo 1925 • The Birth of Radio

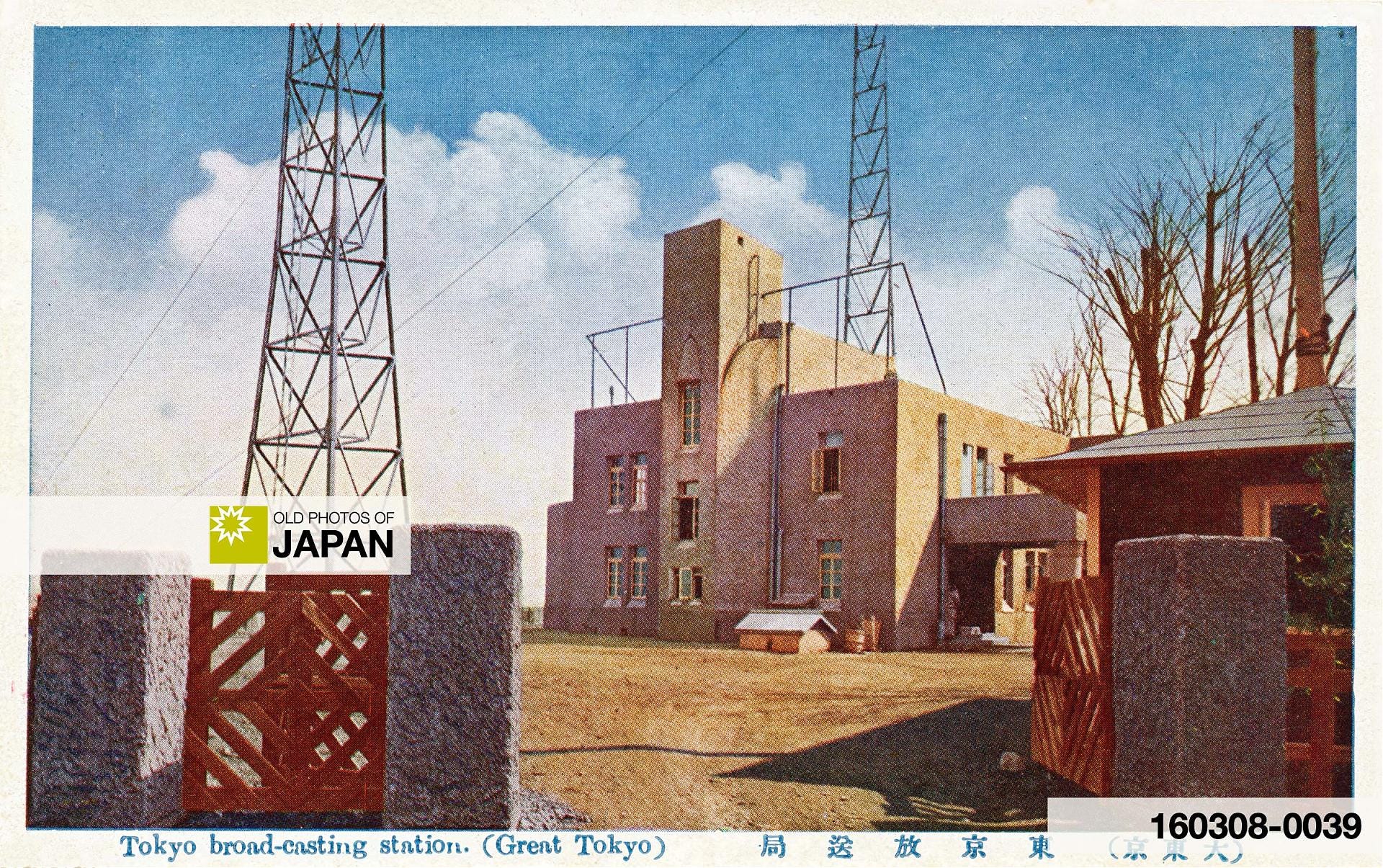

This unassuming building at Tokyo’s Atagoyama is considered the birthplace of Japanese broadcasting, as well as Japan’s public broadcaster, NHK. Regular radio broadcasts started here on July 12, 1925.

Read this article on the site | Comment on this article.

Japan’s very first radio broadcast took place a few months earlier, on March 22. However, it was not transmitted from Atagoyama, but from the library of the Tokyo Higher School of Arts and Crafts in nearby Shibaura. The school was used as a temporary broadcasting station.1

At 9.30 in the morning that day, the Tokyo Broadcasting Station announcer started the broadcast with the station’s call sign. He sounded as if he was talking over the telephone to someone hard of hearing, exaggerating his intonation, and carefully extending the pronunciation of each letter: J . O . A . K.

Considering the announcer’s phone-like enunciation, it seems appropriate that at the time, radio was called wireless telephone listening (聴取無線電話, chōshu musen denwa).

After the sign-on, station governor Shimpei Goto (後藤 新平, 1857–1929) talked about his hope that radio would offer listeners equal access to the benefits of modern culture, a higher quality of family life, and better public education. He expected that the new medium would invigorate Japan’s economy.2

Because of this historical broadcast, March 22 has become Broadcasting Memorial Day (放送記念日, hōsō kinenbi).

On this day, established by NHK in 1943 (Showa 18), NHK holds an event at NHK Hall in Shibuya. Here it presents the Broadcasting Culture Award (放送文化賞, Hōsō Bunka-Shō) to prominent figures who have contributed to the world of Japanese broadcasting.

Tokyo Broadcasting Station was founded in 1924 (Taisho 13), a year before the historical first broadcast. Separate broadcasting organizations were created in Osaka and Nagoya, with the respective call signs JOBK and JOCK. These three populous cities were selected first because it enabled the weak radio waves of the time to reach the largest possible number of people.3

The three stations merged in 1926 (Taisho 15) to become the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (日本放送協会, Nihon Hōsō Kyōkai), now better known as NHK. It modelled itself on the BBC of the United Kingdom.

NHK’s second radio network began in 1931 (Showa 6), while a third radio network (FM) was launched in 1937 (Showa 12).

These days, everybody walks around with a mobile phone, so it is easy to assume that everybody had a radio. The reality was quite different. There was no infrastructure, radio towers had to be built, and radios were an expensive luxury product. A radio cost between 30 and 200 yen, at a time when the starting salary of an elementary school teacher in Tokyo was 25 yen per month.

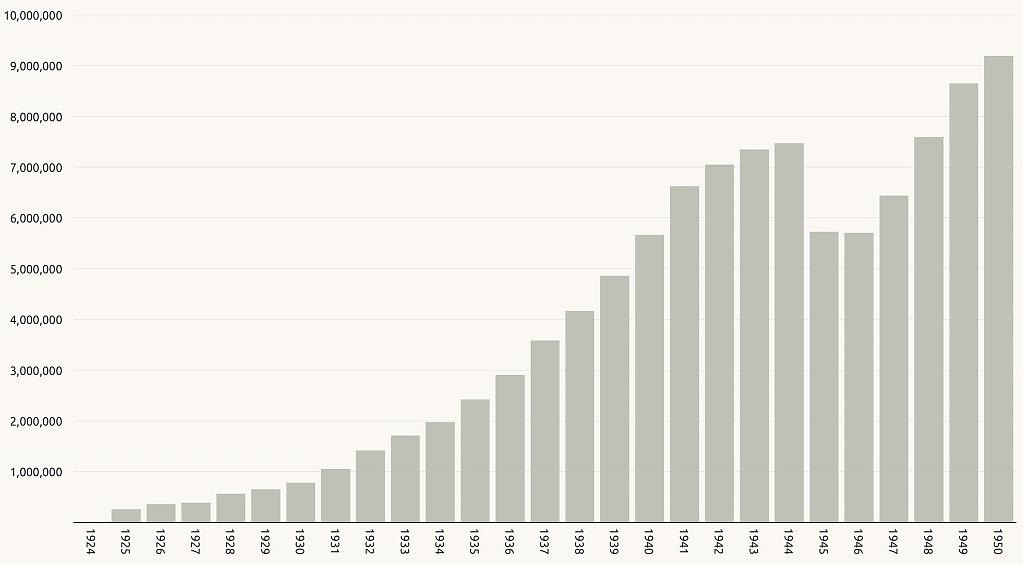

Thankfully for us, radio listening fees (ラジオ放送聴取料, radio hōsō chōshuryō) were required, as well as a listening license4 from the Ministry of Communications (逓信局 Teishinshō). So, we have a pretty good picture of how many households had a radio set, and how this changed over the years.

In 1935 (Showa 10), on a population of 70 million, there were 2.4 million households with a radio. As there were about 13 million households5, this means that there was only one set for every five to six households.

By 1941 (Showa 16), at the start of the Second World War, the number of sets had tripled to 6.6 million (on 14.3 million households), or about one set in every other household.6

Radio sets decreased in 1945 (Showa 20) when city after city was pulverized by American air raids. But after the war, the number of radios increased again. As of April 1, 1968 (Showa 43), radio fees were no longer required and by the seventies, in spite of the competition from television, many households had multiple radios.

To put the above figures in perspective, the table below shows the approximate percentages of Japanese households with a radio set between 1924 and 1950. The percentages are surprisingly low.

These figures can be slightly misleading, though, because the home was not the only place to listen to the radio. People would gather at radio shops and other locations where broadcasts could be heard.

And in spite of the low penetration of households, radio did have an enormous impact at home. Especially in Tokyo. This is illustrated by NHK producer Tokujiro Kobayashi’s recollection of the radio drama Tankō no naka (炭鉱の中, In a coal mine). It was aired on the evening of August 13, 1925. The piece was set in a coal mine after an electrical failure. Because the action took place in complete darkness, the announcer told listeners to turn off their lights.

Kobayashi looked down from the twenty-six-meter-high Atagoyama, where the studio was located, and saw “the lights in the houses down below going off one by one.”

A magazine reporter who witnessed the broadcast described it more dramatically:

There was an unusual tension in the air, like Paris bracing itself for a night attack from a German Zeppelin. All the homes listening to the radio were shrouded in darkness.7

This article is the first in a short series about Japanese radio.

Stay tuned!

東京高等工藝学校 Currently known as Tokyo Institute of Technology High School of Science and Technology (東京工業大学附属科学技術高等学校). CPRA, 企画部広報課 君塚 陽介, ラジオ放送の誕生と実演家の権利 Retrieved on 2022-03-20.

NHK Museum of Broadcasting, Atagoyama, the Birth Place of Japanese Broadcasting. Retrieved on 2022-03-20.

CPRA, 企画部広報課 君塚 陽介, ラジオ放送の誕生と実演家の権利 Retrieved on 2022-03-20.

聴取無線電話私設許可書

e-Stat, Statistics of Japan, Ordinary households and quasi-households (1920 to 1985). Retrieved on 2022-03-19.

日本放送出版協会・NHKラジオ年鑑1951年版

Yasar, Kerim (2018). Electrified Voices: How the Telephone, Phonograph, and Radio Shaped Modern Japan, 1868–1945. New York: Columbia University Press.