Help save Japan’s visual heritage of daily life

Your support helps me find, acquire, scan, restore, research, conserve and share irreplaceable images of life in old Japan.

If you can afford it, please consider supporting my work by donating, or purchasing art prints in the Old Japan Shop.

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | APPENDIX

This is Part 1 of an essay about how people stayed warm in old Japan.

A man and a woman are adjusting the fire of an irori (囲炉裏), an open fire centrally located in the main room. For centuries it was the primary source of heat in many Japanese dwellings, as well as the seat and beating heart of family and village life.

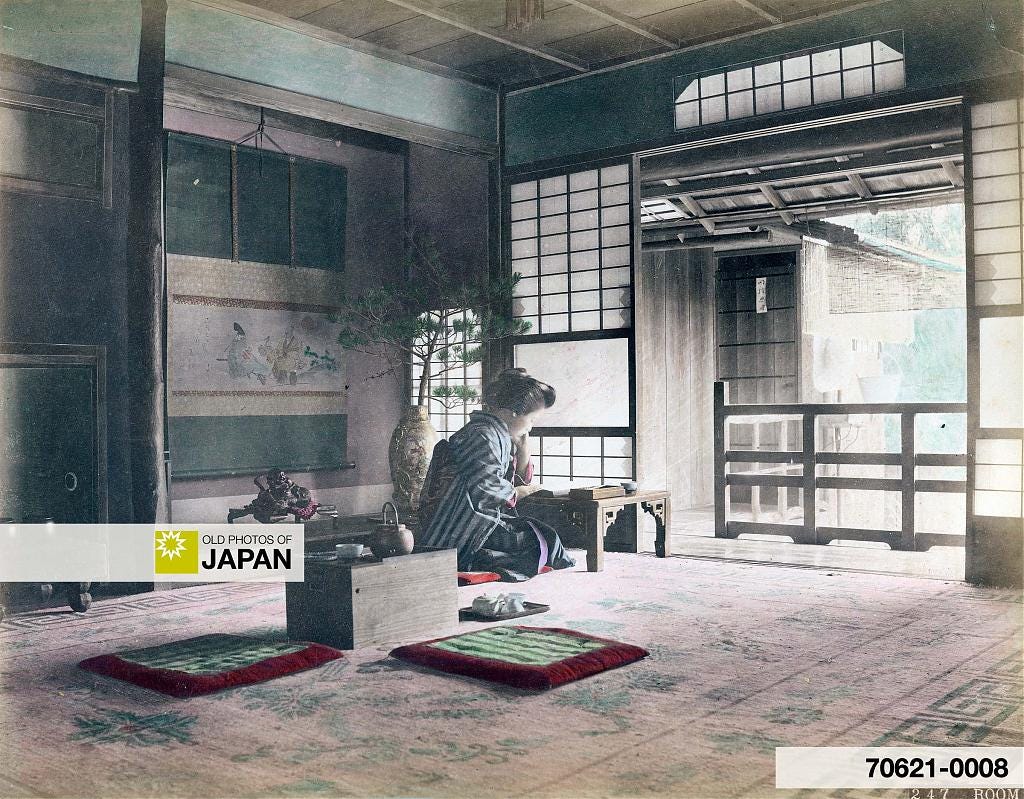

Staying warm in Japan used to be remarkably challenging. Much of Japan has a humid subtropical climate with hot and humid summers. This encouraged Japan’s famously open architecture featuring removable sliding doors. The wind could blow right through the house, offering welcome relief during the muggy summer.

We are used to doors and windows with glass panels that let in the light but keep out the weather. Even during the Meiji Period (1868–1912) these were extremely rare in Japan. They only gradually became common after domestic production of glass started around 1903 (Meiji 36).1

The sliding doors separating the interior from the outside were therefore either wooden shutters (雨戸, amado) or latticed frames with translucent paper (障子, shōji). The shōji—often punctured and torn—let in light but offered no protection against the weather. The amado kept out most of the weather, but blocked light.

This construction was helpful for hot sunny days, but dark, gloomy, and frightfully cold during bad weather. The thin sliding doors made space heating impossible so the inside temperature was essentially the same as outside. Water left overnight in winter would be frozen in the morning.

American educator Alice Mabel Bacon (1858–1918) who taught in Japan for several years describes the issues of such a home in her 1894 book A Japanese Interior:2

My little paper dining-room is quite uncomfortably cold, and has no heating arrangement except hibachi [braziers]. Two sides of the rooms are made entirely of sliding paper screens opening out of doors, so that it is very much exposed to the weather. There are wooden outside screens that can be closed, but they shut out the light, so I can only keep them closed when I wish to take my meals by lamplight. I have ordered new screens with glass set in them, and then I can let in the light and keep out the air, and hope to be able to make my dining-room comfortable, with a hibachi, in all but the worst weather.

A Japanese Interior (1894), 38

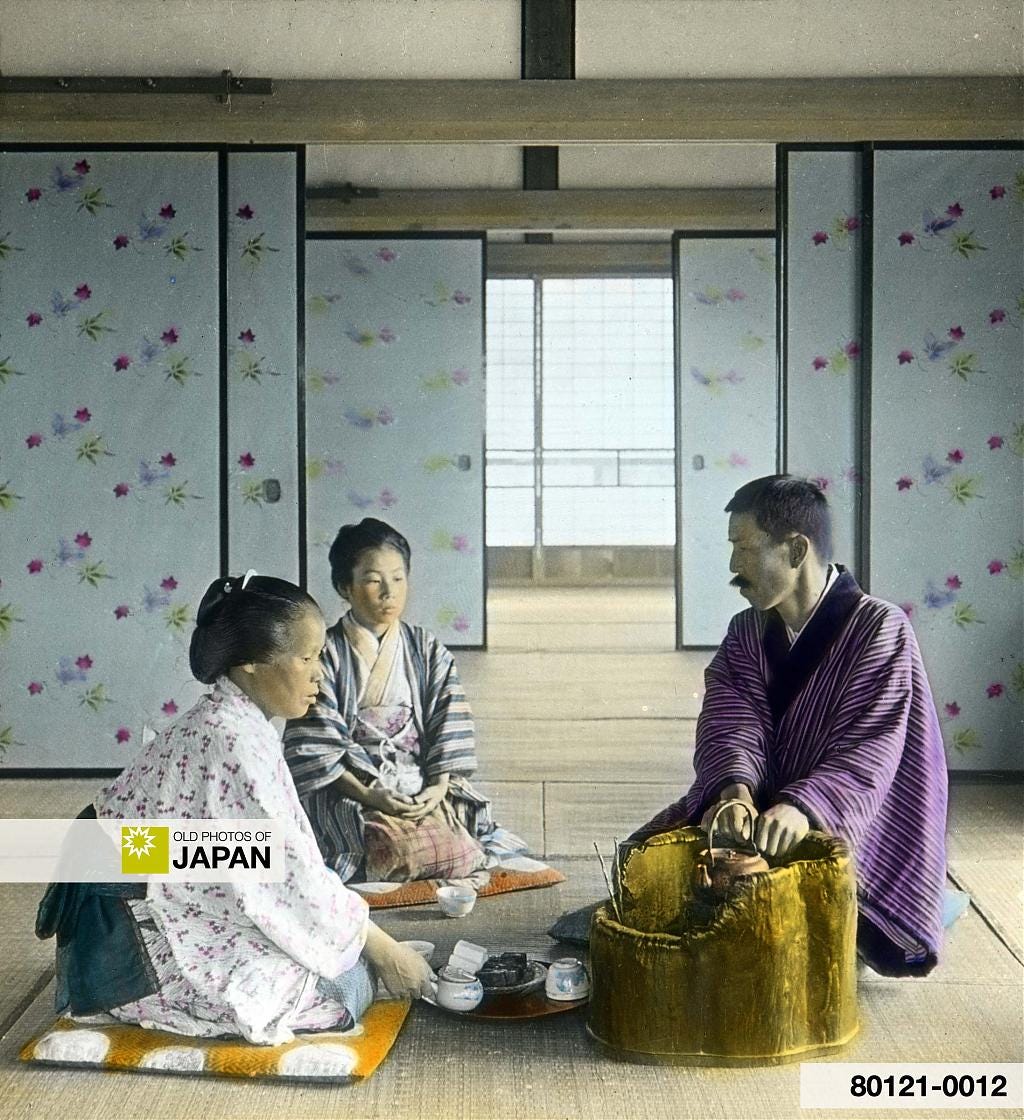

In Home life in Tokyo (1910), Japanese author Jukichi Inouye explains how the Japanese fought the cold with warm clothes padded with cotton (綿入れ, wata’ire), hibachi braziers, and exposing the main rooms to the south:3

No people short of savages probably lead a more open-air life than we do in our wooden houses. Our paper sliding-doors, which are our only protection against wind and cold in winter, admit both light and air; and we provide personally against the cold by wearing wadded clothing and huddling over braziers, while in summer all the sliding-doors are often removed to let the cool breeze blow through the house. It becomes, then, an important matter in building or selecting a house to see that its principal rooms are so arranged as to get the warm rays of the sun in winter and the cool breezes in summer. As both these are to be obtained from the south, the principal rooms are made to expose their open side to that direction.

Jukichi Inouye, Home life in Tokyo (1911), 27–28

Irori

Surprisingly, neither Bacon nor Inouye mentioned how the majority of people tried to stay warm—by sitting as close as possible to the irori, a chimneyless in-house open firepit. Perhaps because by this time the irori was rare in large cities. In the countryside however it was found in almost every single dwelling, as well as in countless inns and businesses.

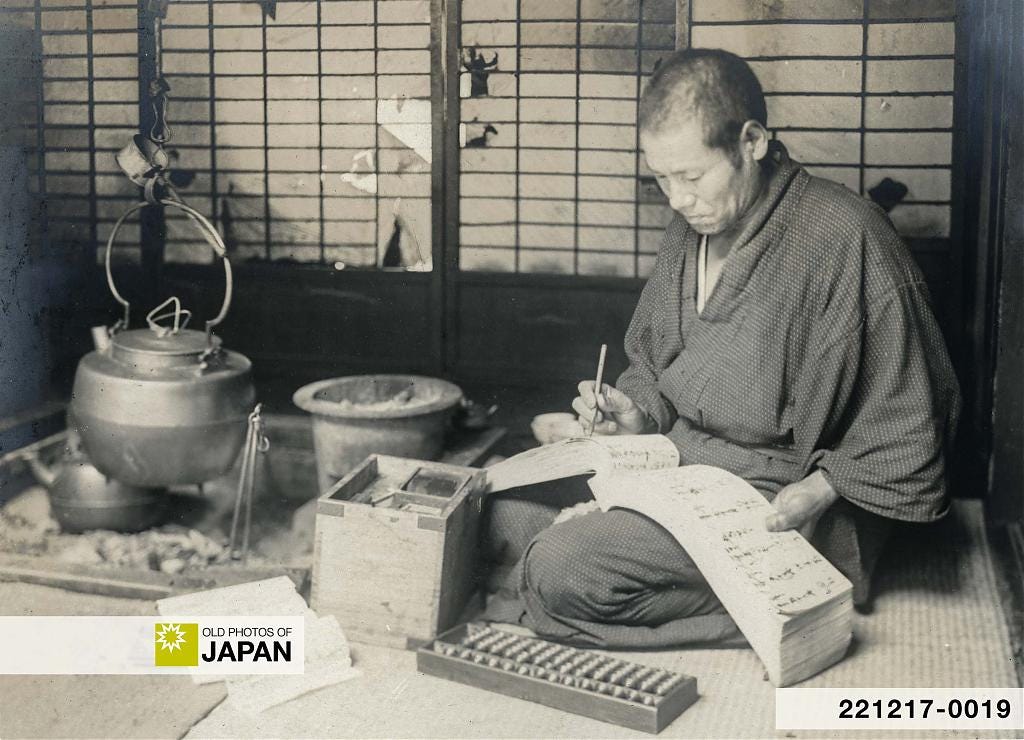

The irori was especially significant to the many millions of farming families. It was their main source of heating and lighting, as well as the place where they cooked, ate, worked, relaxed, gossiped, and dried their clothing. Many families even slept here during very cold nights.4

As the central place for household chores, meals, and gatherings the irori was the beating heart of rural families and communities as can be seen in the final scenes of this 1962 (Showa 37) documentary about minka (民家, traditional buildings for farmers, artisans, and merchants).

When anthropologists John and Ella Embree (Ella’s name later became Wiswell) studied the small agricultural village of Suye in Kyushu’s Kumamoto Prefecture in the mid-1930s the irori became a crucial place for collecting information.

Wiswell found that as a heating and a gathering place the irori warmed the body as well as the soul. She later explained how much she enjoyed sitting by the irori:5

Some of this constant wandering about the village was fun. On a cold day it was pleasant to sit by the fire-pit and have tea and pickles and smoke the tiny pipe that all older women used, while listening to gossip.

Ella Wiswell, The Women of Suye Mura (1982), xxiv

During cold winter evenings the irori’s warmth and light naturally drew people together transforming it into a sacred place for telling and performing tales.

The irori was where storytellers—parents and grandparents, the village’s elderly storytellers, and traveling professionals like traders, teachers, artists, monks, dancers, monkey trainers, singers—met their audience.6

Architectural historian Takeshi Nakagawa (中川武, 1944) who grew up in a house with an irori in the 1940s and 1950s described in his book, The Japanese House: In Space, Memory, and Language how in his mind hearing “thrilling stories” had become “indelibly associated” with the irori:7

Of all my memories linked with the irori, the one that stands out is the pleasure of sitting by the hearth with my older brother and listening to stories about horses, or yarns about weird things that had happened in the neighborhood, told by a distant relative who lived nearby. I’m not sure who he was, exactly, but he was a good storyteller. The strange excitement his tales produced has become indelibly associated in my mind with the hearthside, so that now it seems that I could never have heard such thrilling stories anywhere else.

Takeshi Nakagawa, The Japanese House (2005), 94–95

SUPPORT OLD PHOTOS OF JAPAN

Help me research and save Japan’s visual heritage of everyday life.

Notes

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 60–61.

Bacon, Alice Mabel (1894). A Japanese Interior. Boston, New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 38.

Inouye, Jukichi (1910). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 27–28.

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 52.

Smith, Robert J.; Wiswell, Ella Lury (1982). The women of Suye Mura. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, xxiv.

Read Studio, 1880s • The Way of the Kiseru for a discussion of Japan’s pipe culture.

Petkova, Gergana (2021). Japanese Folktales and the Storytelling Tradition — Spatiotemporal Framework, Performance and Experience in Sprachlich-literarische “Aggregatzustände” im Japanischen: Europäische Japan-Diskurse 1998–2018. Berlin-Brandenburg: BeBra Wissenschaft, 129–130.

Nakagawa, Takeshi; Harcourt, Geraldine (2005). The Japanese House: In Space, Memory, and Language. Tokyo: International House of Japan, 94–95.

There is another detail about the "minka": it is often elevated from the ground on poles, which in Japan are often short, but often still present (for example the "this teahouse has become one" photo). The "minka" is in effect a raised platform covered with a heavy roof, and temporary paper/wood panels on the sides.

Compare with the design of northern chinese or korean houses, which are usually the opposite: they are built around a central courtyard, in bricks or stone or wood, with rooms on the four sides around the courtyard, and a regular tiled roof; the design is suitable for winter.

The "minka" type of house is common in south-east Asia, where the weather is tropical, and houses are often built on ground subject to flooding (and the platform is often on higher poles than in Japan), and the lack of permanent walls and the heavy roof on a flexible lattice works well with common typhoons/monsoons. Then all aspects of the design make a lot of sense.

This point out that the lower classes of Japan most likely migrated to Kyushu via the Ryukuku islands from the area around Taiwan. But many japanese are reluctant to consider that possibility because of the political implications (the upper classes obviously came from a different area).

The question is why an house type designed for a completely different climate persisted in Japan for so long. My guesses are that house building is very conservative, and more importantly that house type is resistant not just to flooding and typhoons/monsoons but also to earthquakes.