How Radio Gymnastics Conquered Japan

Female students doing calisthenics in 1936 (Showa 11). Calisthenics became astonishingly popular in Japan after the radio program Rajio Taisō (ラジオ体操, Radio Gymnastics) was started in 1928 (Showa 3).

Read this article on the site | Comment on this article.

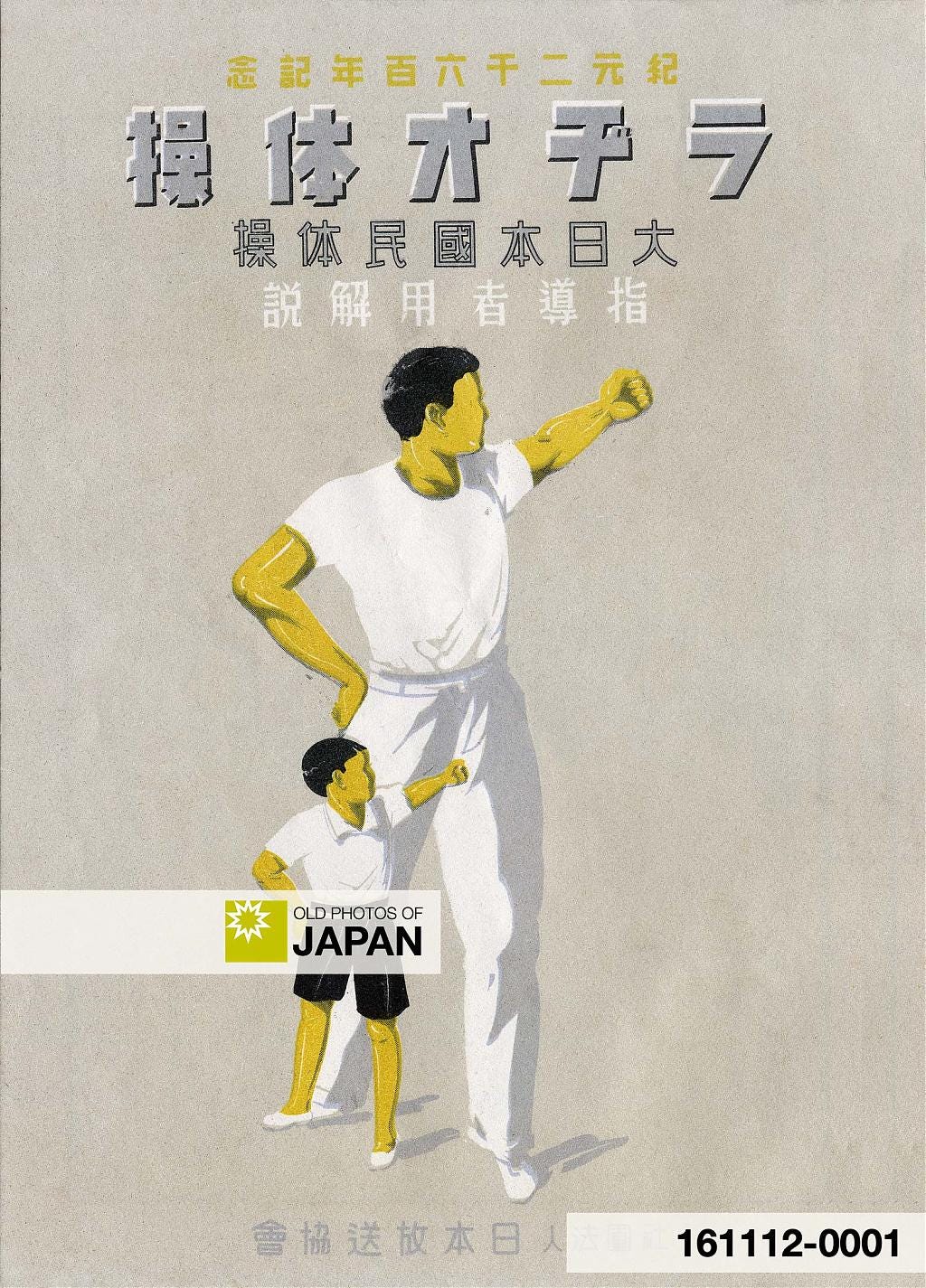

The very first Rajio Taisō program was broadcast from 7:00 in the morning of November 1, 1928. Launched to commemorate the enthronement ceremonies of Emperor Hirohito (昭和天皇ご即位の大礼を記念), which were held that month, it was hosted by military officer Riichi Egi (江木理一, 1890–1970). He only had his voice, and the assistance of a pianist, to persuade people to do the exercises.

Egi didn’t get off to a good start. On the first day, he showed up at the studio at Tokyo’s Atagoyama all dressed up in military uniform, complete with military sword. In a commanding voice, he shouted “Attention! I’m going to start radio calisthenics now.”1

He immediately realized this was not appreciated, and from the second day on he arrived at the studio in his gym uniform with a big smile on his face and attitude to match. Egi’s cheerful and energetic presentation, and his greeting “Good morning, everyone everywhere. Here we go, be lively, and let’s start exercising” made the program exceedingly popular.2

Although the listeners couldn’t see him, Egi did the exercises himself right in front of the microphone. He continued doing this until he retired from the program in April 1939 (Showa 14). This, however, was not the end of his Rajio Taisō career. After his retirement, he spent many years traveling all around Japan to promote radio calisthenics.

Because everybody in Japan now knows the program it comes as a surprise that for the first three months the program was only broadcast in Tokyo. It finally went nationwide from February 12, 1929.

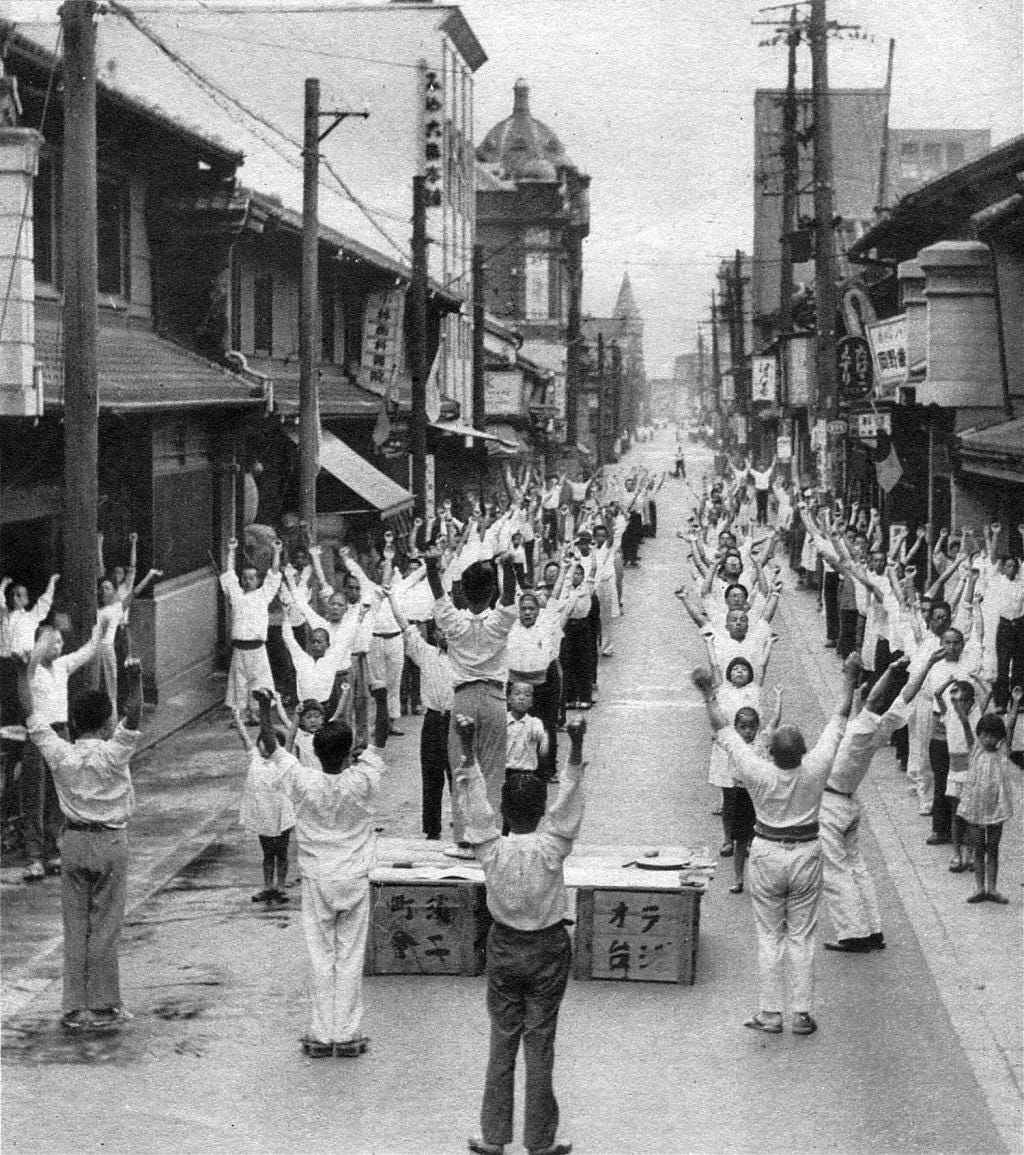

People initially practiced at home. But in July 1930 (Showa 5), a policer officer at the Kanda-Manseibashi Police Station (神田万世橋署) started a radio gymnastics meeting for the children in his neighborhood.

This idea quickly spread, and soon people all over Japan practiced the exercises at schools, workplaces, neighborhood associations, and even outside on the street, in the park, or at the local shrine. By 1938 (Showa 13), some 157 million people participated in Rajio Taisō.3

Beginnings

Rajio Taisō, or Great Japan National Health Insurance Gymnastics (大日本国民保険体操) as it was officially known, was the brainchild of the Postal Life Insurance Bureau (簡易保険局) of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (逓信省). In 1920, the average life expectancy in Japan for women was only 43 years, for men 42.4 It was hoped that calisthenics would help improve the health of the entire nation.

The idea actually came from abroad. In 1925, employees of the bureau were sent to the United States to study the insurance business there. Here they encountered the Metropolitan Life Health Exercises radio broadcasts, which the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company had just started. Their 15-minute exercise routines were broadcast from early April 1925 through 1935.

An article was published in the Journal of the Telecommunications Association of Japan (逓信協会雑誌) to promote the idea of such a program for Japan. It advocated the development of “somewhat hobbyistic” exercises that could be done “easily by anyone, regardless of age or gender” and “anywhere, inside or outside.”5

To bring the concept to life, the Postal Life Insurance Bureau cooperated with the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, the Ministry of Education, and other organizations.

Calisthenics didn’t just suddenly fall out of the sky in 1928. It had a long history in Japan, which undoubtedly helped to make Rajio Taisō such a great success.

Gymnastics in school education had already begun in 1872 (Meiji 5), after the new school system (学制) was promulgated. One of the textbooks published during this period was the illustrated manual of gymnastics, Taisou Zukai (體操圖解).

The manual introduced gymnastics as a way to keep both body and mind healthy. The first sentence read, “Gymnastics is an excellent technique to keep the body healthy and to improve depression and anxiety.”6

But in addition to this individualistic approach, there was also another more statist viewpoint. Physical education at schools was increasingly considered to be an effective way to improve discipline in group activities, and to prepare boys for military service. This role started to dominate after the educational reforms of 1886 (Meiji 19) when gymnastics became a compulsory subject in elementary schools.

In a report from around 1887, Minister of Education Arinori Mori (森有礼, 1847-1889) suggested that “the subject of physical education should be separated from the Ministry of Education and placed under the management of the Ministry of the Army, and pure military style physical education should be given to the students by military officers.” In this way, he argued, “Students will take on the superior character of military men. A spirit of loyalty to the Emperor and love of country will be encouraged.”7

This never happened. The military just didn’t have the personnel, nor the budget, for such an enormous task. It does however demonstrate how strongly physical education was now seen as a benefit to the state rather than the individual, a sentiment that would express itself even more strongly in the militaristic 1930s.

Swedish Free Gymnastics

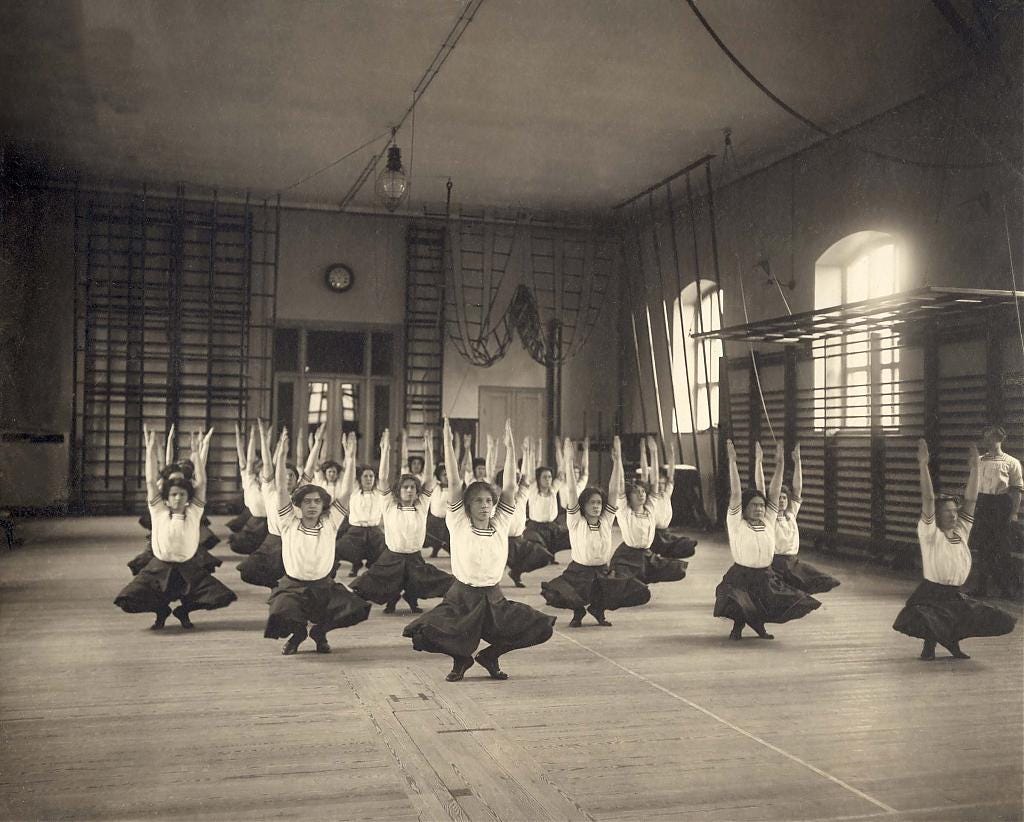

Something important happened around the start of the 20th century, though, that would temporarily interfere with a militaristic approach to physical education. An increasing number of girls enrolled in elementary schools. This gave the impetus to explore new forms of physical education.

Around this time, Welsh scholar Elizabeth Phillips Hughes (1851–1925), Physician Motokuro Kawase (川瀬元九郎, 1871–1945), educator Aguri Inokuchi (井口 阿くり, 1871–1931), and others introduced Swedish free gymnastics. This had an enormous impact on how physical education would be conducted and perceived.

Kawase wrote two books about the subject in 1902, and Inokuchi started introducing Swedish free gymnastics from 1903. Their work was so influential that Swedish free gymnastics was officially adopted as the preferred system for physical education at Japanese schools in 1905. Interestingly, both had encountered this form of gymnastics while studying in Boston.8

The origins of Swedish free gymnastics go back to the early 1800s when Pehr Henrik Ling (1776–1839) developed a holistic system of physical exercise that developed strength, elasticity, balance, coordination, respiration, rhythm, neuromuscular control, skill, and willpower.

Ling believed that haphazard movements produced few corporeal, and no mental benefits. He argued that stretching particular muscles with a determined force to provide a properly calculated resistance, and limiting movements to just a few repetitions, was the true recipe to a healthy and balanced body and mind.9

Unlike most modern exercise regimens, Ling’s method didn’t just aim for strength. Calisthenics comes from the ancient Greek words kállos (κάλλος, beauty) and sthenos (σθένος, strength), and beauty was an essential aspect of his system. The movements were designed to flow into each other as if in a dance. Because of the importance of these transitions, it actually became known as the movement cure.

Ling intentionally created exercises that developed strength by using the practitioner’s own body weight as resistance. As they were done empty-handed, his system became known as free gymnastics. With no need for equipment, it could be practiced anywhere, anytime, by anyone.

It became enormously influential and spread all over Europe and the United States, including Boston where both Kawase and Inokuchi ended up studying the system.

A fascinating footnote is that new comfortable clothing was developed to allow female students to move freely while practicing these exercises. This photograph from ca. 1900 showing German schoolgirls in Hamburg in their uniforms will look surprisingly familiar to present-day Japanese high school students.

Even after Swedish gymnastics were officially adopted in 1905, military-type exercises continued to be used. The two systems co-existed. However, postcards published by schools during this period suggest that morning exercises consisted mostly of Swedish style calisthenics.

So when Rajio Taisō started in 1928, the great majority of Japanese had already experienced practicing free calisthenics every day as students. It was just a small step to now do such exercises with the assistance of a radio program.

Simultaneously, the Japanese familiarity with free gymnastics meant that its philosophy and practice greatly influenced the Rajio Taisō exercises. An influence that endures to the present day.

Radio Calisthenics Today

Rajio Taisō continued through the war years. But the American occupation forces banned the program in 1946 (Showa 21). With its mass attendance and loud music blaring from loudspeakers, it was seen as militaristic. NHK quickly reworked the program, but in the postwar chaos it did not catch on and Rajio Taisō was canceled in 1947.

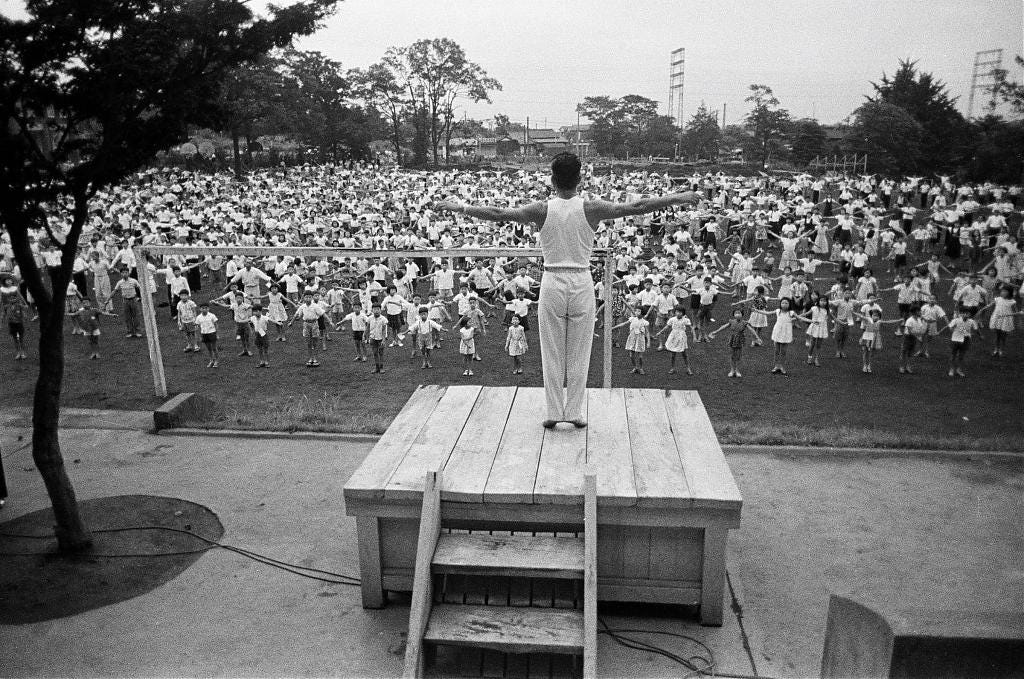

However, as Japan slowly started to recover, more and more people wanted Rajio Taisō to return. It was finally relaunched in 1951 (Showa 26). Once again, it soon became extremely popular. During the summer, massive events were organized that attracted many thousands of participants.10

The news broadcast below is from 17 July 1957 (Showa 32), incidentally also the year that TV broadcasts of the calisthenics program started. It shows a Rajio Taisō event in Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture that attracted almost 5,000 people.

Even today, events during summer still attract many thousands of participants. And all year through, you can observe participants in the park participating in the program from 6:30 in the morning, while companies all over Japan start their workday with the exercises.

During the pandemic, there were even zoom meetings for people working at home so they could do radio calisthenics together with other colleagues working at home.

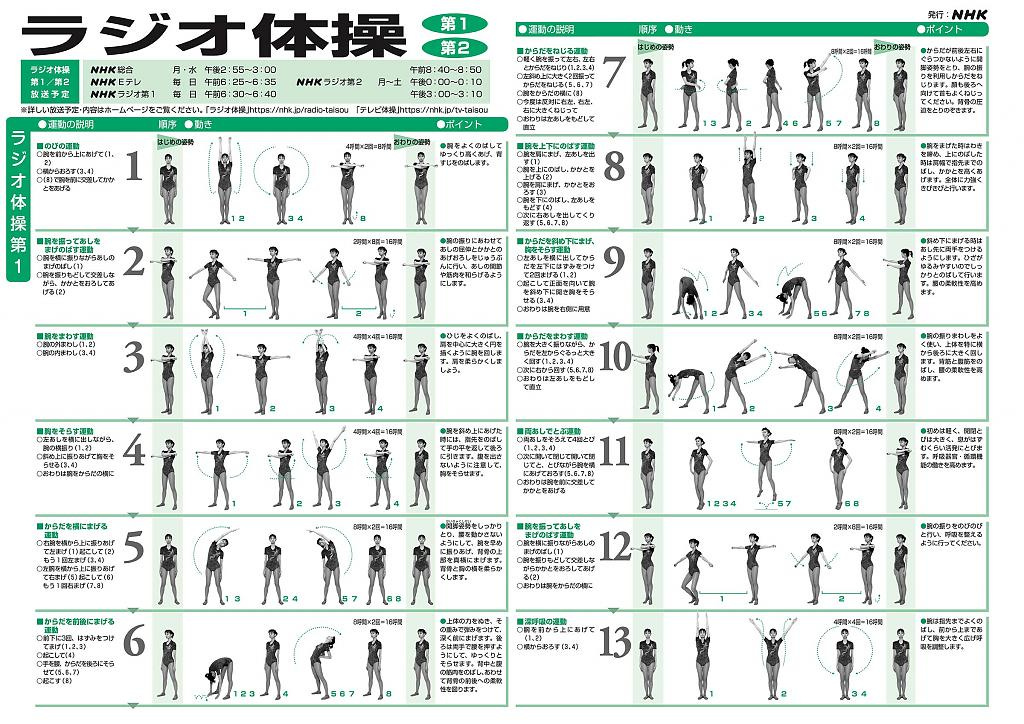

Rajio Taisō’s modern exercises are designed to both exercise and relax the body.

Especially important is how the momentum from one action flows into the next motion, which is then followed by a slight pause called ma (間). This fleeting interval between movements is just as important as the movements themselves. It also gives the exercises a certain aesthetic that reminds one of the dance-like movements of the original Swedish free gymnastics.

Ma, empty space, is a familiar concept in Japanese culture. It is an essential part of Japanese architecture, art and martial arts. Even Japanese organizing consultant Marie Kondo makes use of ma by making emptiness significant.

Benefits

The benefit of Rajio Taisō lies not merely in the exercises themselves, but also in the routine that the program establishes.

It starts at 6:30 am and is performed live on the radio. So, to participate in Rajio Taisō at the park, you have to leave at a certain time, get up at a certain time, go to bed at a certain time, and have dinner at a certain time. It establishes a complete routine for the whole day. Which probably explains why so many retired people enjoy participating.

Many Japanese who have grown up with radio calisthenics also feel that the exercises foster a sense of community. After the triple disaster in 2011, countless groups started such programs to create a feeling of unity for displaced people.

One of them was a community revitalization project in Ishinomaki, Miyagi Prefecture, a city that was partly wiped off the map by the tsunami. The project shot the video below on September 10th and 11th, exactly half a year after the Great East Japan Earthquake devastated the area, to raise funds for the survivors.

As the Ishinomaki video shows, the attraction is not limited to the elderly. Several years ago, Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward took advantage of this universal attraction by creating a Rajio Taisō video to promote the area’s diversity on YouTube.

It is fascinating to see how the program, which started on the then new medium of radio almost a century ago, has so easily adapted to new media, from TV to the internet. The National Rajio Taisō Federation (全国ラジオ体操連盟) even has its own YouTube Channel.

Not bad for an exercise regimen first developed in the early 1800s.

日本放送協会(1977年)『放送の五十年 昭和とともに』日本放送出版協会、40-42「気をつけ! ただ今からラジオ体操を始めます」

ibid.「全国の皆さーん、おはようございます。さあ、きょうも元気で、体操を始めていただきましょう」

Sasaki Takahashi. Rajio Taiso: Japan’s National Exercises. Highlighting Japan, October 2019, 14–15. Retrieved on 2022-03-28.

Nippon.com Japan’s Population Data in 1920 and Today. Retrieved on 2022-03-28.

Japan Post Insurance Co. 1916年~1942年 国民保健体操から旧ラジオ体操制定へ「老若男女を問わず」「誰にでも平易にできる」「内でも外でも、いかなる場所でもできる」「多少趣味的な」 Retrieved on 2022-03-28.

夫(そ)レ体操ノ用タルヤ身体ヲ健全ニシ欝憂ヲ暢達(ちょうたつ)スルニ尤(もっと)モ趹(か)クベカラザル妙術ニシテ」

Manzenreiter, Wolfram (2014). Sport and Body Politics in Japan. New York: Routledge, 86—89.

Kimura, Kichiji. The Influence of the Swedish System of Gymnastics on School Physical Education in Japan. Research Journal of Physical Education, Chukyo University 19, no. 1 (February 1979), 13-24.

Ueyama, Takahiro. Capital, Profession and Medical Technology: The Electro-Therapeutic Institutes and the Royal College of Physicians, 1888-1922. Medical History 41 (1997), 150-181.

NHK テレビ・ラジオ体操放送史 Retrieved on 2022-03-28.