Beauties of the Bath

Japan’s bathing culture is considered quintessentially Japanese. No guide book of Japan is complete without instructions on how to take a bath. A short history.

Read this article on the site | Comment on this article.

The Japanese bath first developed as both a religious ritual at Buddhist temples, and a curative practice at Japan’s many volcanic hot springs. Over many centuries, it then transformed into a wide variety of communal places for both hygienic cleansing and social gathering.

The original religious and curative functions still exist. But the modern Japanese bath has become foremost a luxurious form of relaxation, as well as a daily necessity, installed in the home as a mass produced unit.

The Japanese way of bathing has long both delighted and mystified foreign visitors. Many letters and diaries mention the custom. As do countless books about Japan, including the first standard work on Japan written by German naturalist and physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716). As an employee of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Kaempfer lived and worked in Japan in the 1690s, at the Dutch trading station on Nagasaki’s Dejima island.

“Japanese are very great lovers of bathing, and use it every day,” he wrote. This, he believed, was “the reason why the pox spreads so much less, than it would be otherwise like to do in so populous a Country.”1 His detailed descriptions of Japanese baths, like the one below, are still studied by scholars today.2

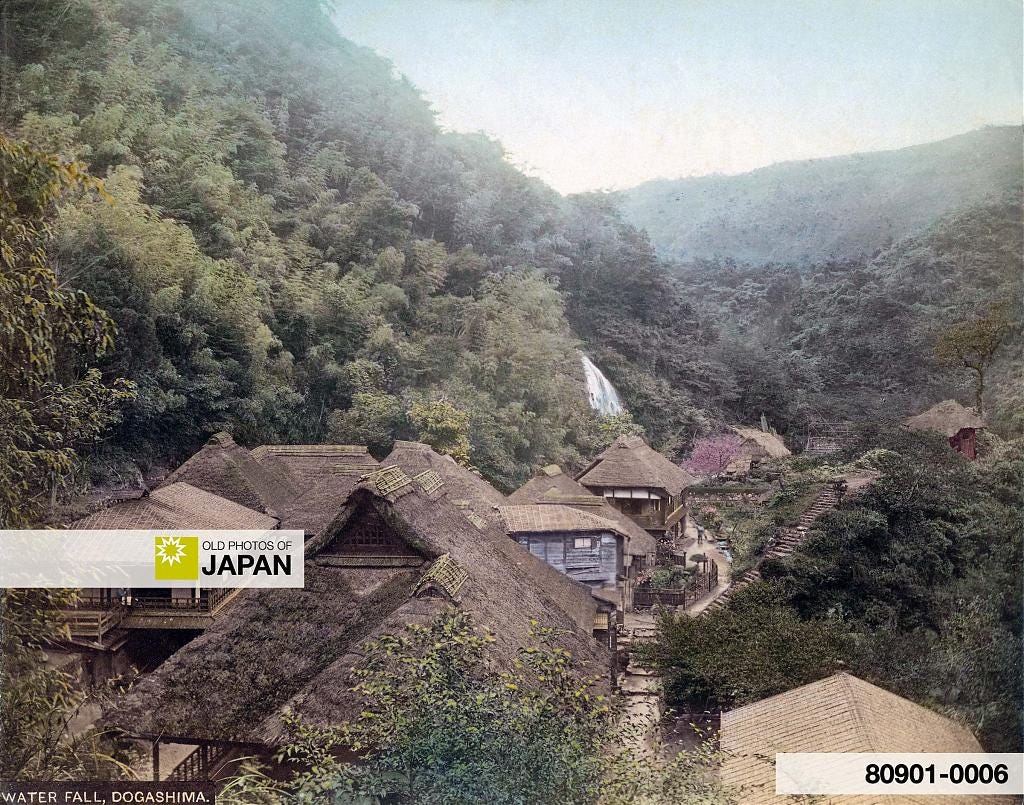

Not far from the village, on the side of a small river, which falls down from a neighbouring hill, is a hot bath, famous for its virtues in curing the pox, itch, rheumatism, lameness, and several other chronic and inveterate distempers. This Bath we had leave to see. I found the place rail’d in with Bambous in a very handsom manner. Within the inclosure was a watch-house, and a small booth for the guests to divert themselves. Along one side of the rails was built a long room or gallery, divided into six smaller rooms, or baths, all under one roof. Every bath was a mat long and broad, and had two cocks, one to let in cold, the other hot water, and this in order that every body might mix it to what degree of heat they can best bear. At the side of this long room was a place for the guests to repose themselves, cover’d with a thatch’d roof.

Engelbert Kaempfer, The History of Japan

This fascination with the Japanese bath continues today. Sentō (public baths), onsen (hot springs), and ofuro (baths) represent the essence of Japan. “To take a bath in Japan with an understanding of the event is to experience something Japanese. It is to immerse oneself in culture as well as water,” wrote American anthropologist Scott Clark in his 1994 book Japan: A View from the Bath.3

One could easily fill a book with such quotations, as well as art inspired by the custom. The Japanese bath enchants anybody who has experienced it.

Even the Japanese themselves love to dive into the topic. A truly limitless stream of Japanese books, television programs, and articles in newspapers and magazines constantly feature the country’s best or most unique baths and how to enjoy them. There are countless promotional events.

Origins

As a ritual with a carefully delimited proces—you thoroughly cleanse yourself before entering the scalding hot water—bathing forms a distinctive component of Japanese culture.

This extends to language. Unlike Western languages where the adjective hot is used to modify water, the Japanese language has a separate word for hot water, yu. Unheated water is mizu.

When looking at the cover photo of the Japanese magazine above, people using a language with a single word would likely just see a lot of water. A Japanese person however, may see two distinctive bodies of water, each offering a totally different experience. Such is the power of yu.4

In linguistics, the brevity law states that the more frequently a word is used, the shorter it tends to be. So it is fascinating that mizu consists of two syllables, while yu has only one.

Baths go back to ancient times in Japan. The Kojiki (古事記), a chronicle of myths and legends compiled during the fifth and sixth centuries, feature many references to bathing. As do the Fudoki, reports on provincial culture dating to the eight century.

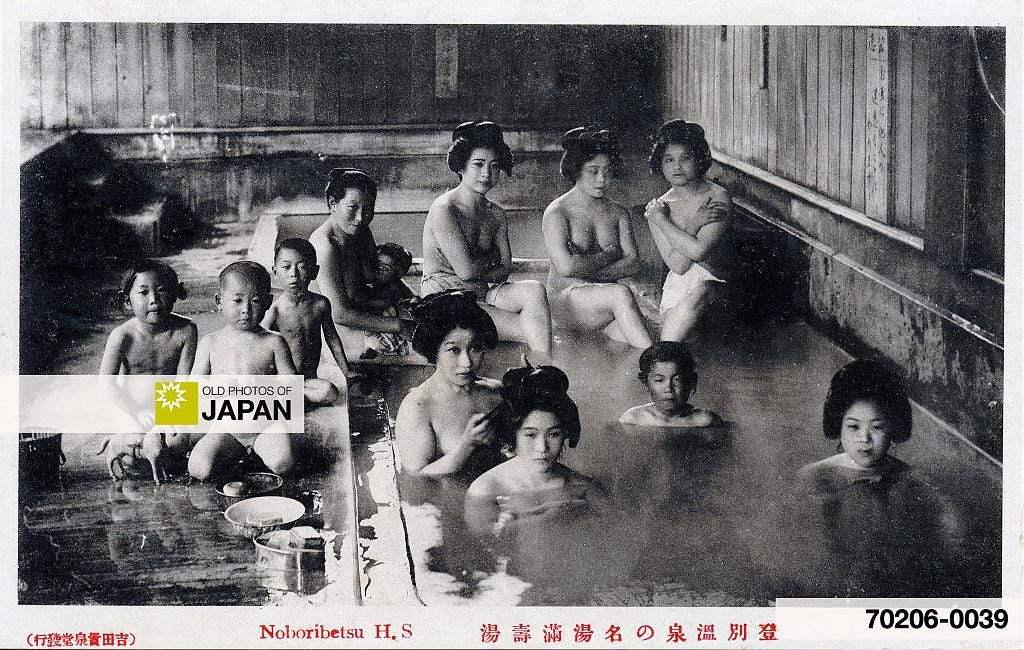

The Izumo no Kuni Fudoki (出雲国風土記), written in 733, describes how men, women, the elderly, and children gathered at a hot spring by the river every day. They sang and partied (酒宴) so much that a market was set up. The bathing made one beautiful and cured any illness, claimed the fudoki. It is believed to be a reference to Tamatsukuri onsen (玉造温泉) in Matsue City, Shimane Prefecture.

People may have bathed in natural springs like at Tamatsukuri onsen, but for economic and social reasons, actual baths were long limited to a narrow elite of courtiers and clerics.

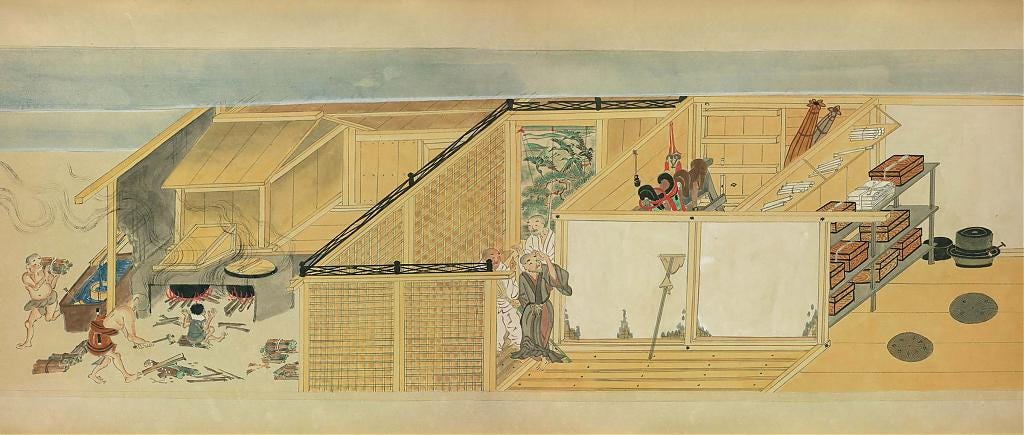

Buddhist temples first introduced bathhouses sometime after the introduction of Buddhism in the sixth century. Nara’s famed Tōdaiji temple, opened in 752 CE and seen as the center of the nation, had such a bathhouse. It was appropriately known as large bath house (大湯屋, ōyuya ).

Priests used baths to purify themselves before conducting religious activities. In Zen monasteries it was also a place to meditate.

Eventually, baths were offered to the poor as social welfare (功徳湯, kudokuyu). Patrons provided funds for heating and loincloths, a practice considered to be as valuable as giving food.5

Baths acquired both religious and curative purposes, the latter greatly aided and inspired by the large number of natural hot springs in Japan. The therapeutic baths developed separately and were dependent on the availability of hot springs.

The most famous one was at Arima, near Kobe. According to the Nihon Shoki, Japan’s second oldest history book, Emperor Jomei (593–641) spent 86 days bathing in Arima in 631, while Emperor Koutoku (596-654) spent 82 days in 647.

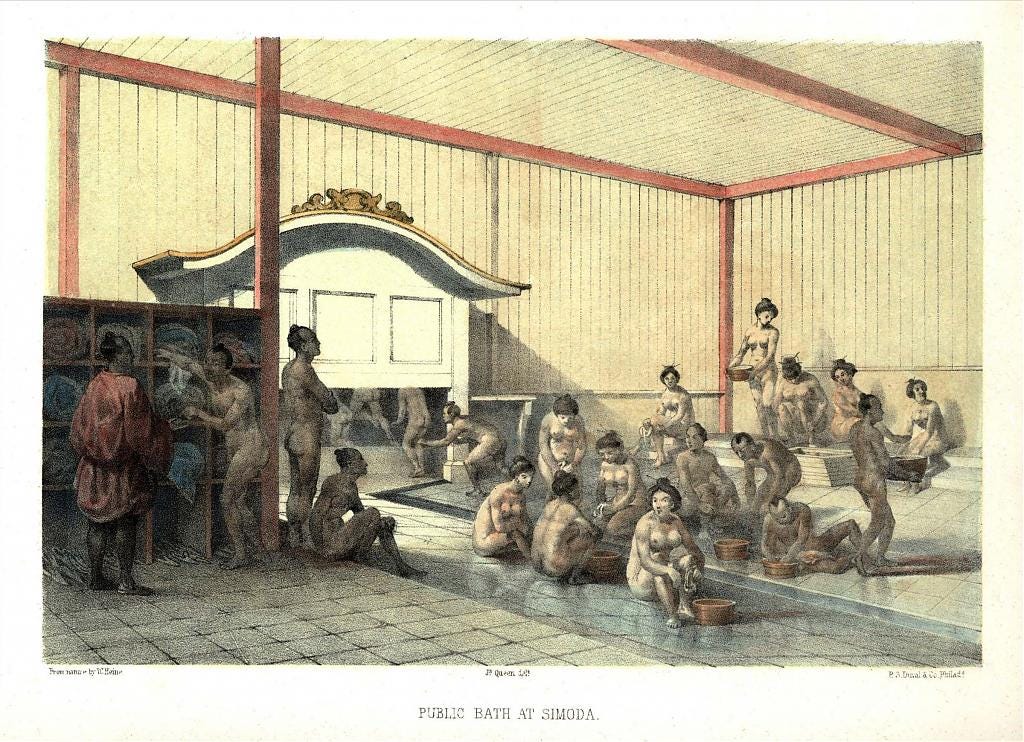

During the 15th and 16th centuries, when hygienic cleansing had become an important aspect of bathing, the bath slowly turned into a place to gather and socialize, a place of communal recreation.

By the mid-16th century, public baths had become common in many of Kyoto’s neighborhoods. At the dawn of the Edo period (1603–1868), bathing had become common pretty much all over Japan. It was now an important cultural institution. Sentōs and onsen were everywhere.6

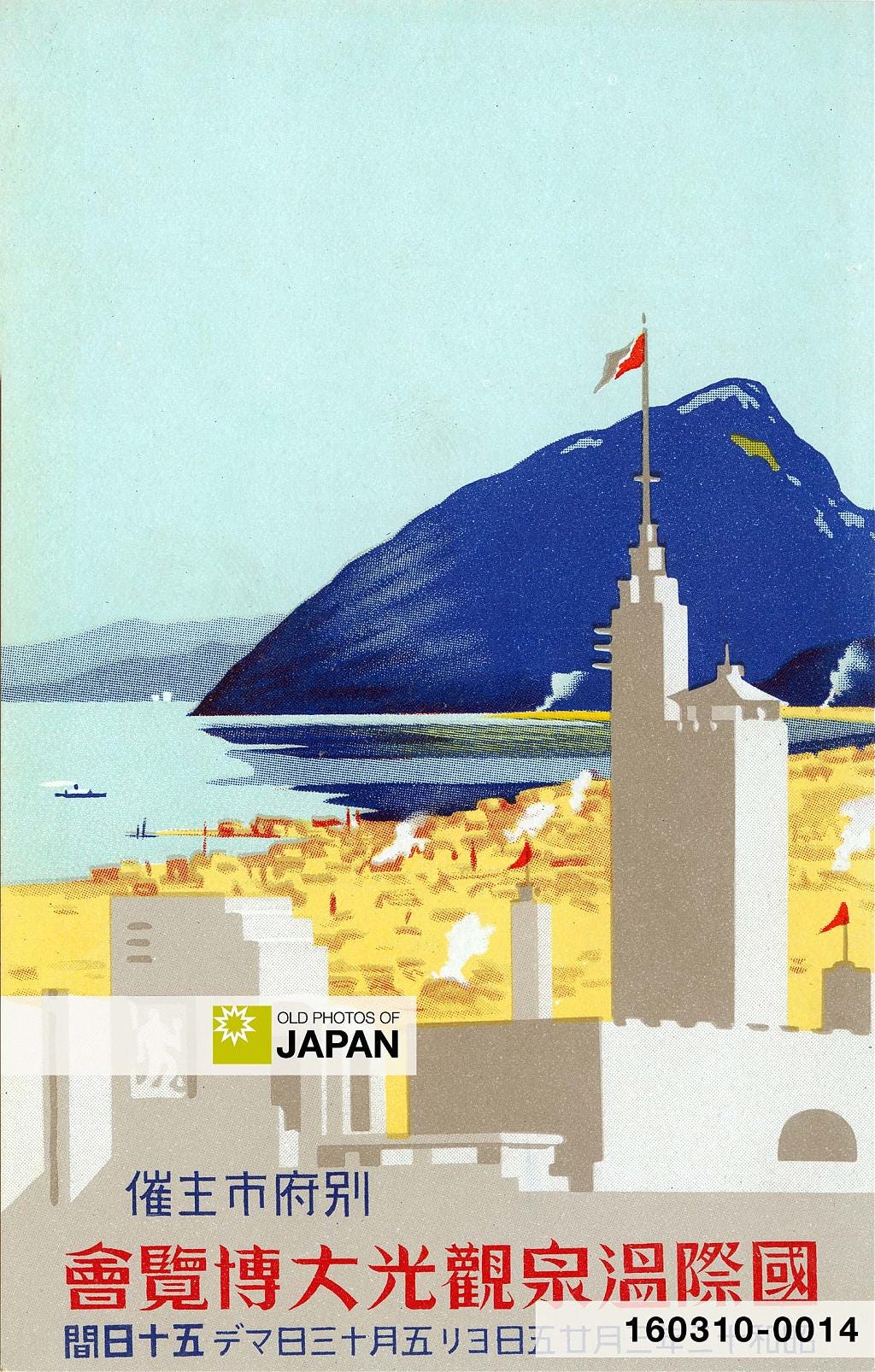

After Japan started to build a railway network in the second half of the 19th century, onsen became even more popular. A burgeoning middle class and affordable travel brought people to Japan’s ancient hot springs in droves.

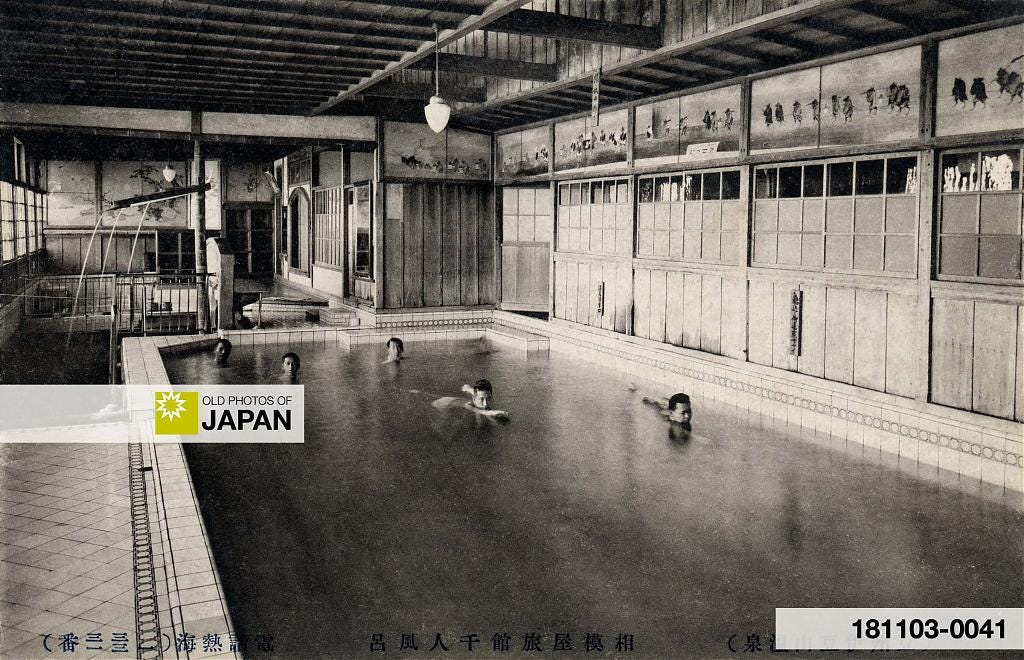

The resulting competition between inns gave birth to increasingly larger baths. In the 1930s, an inn in Shizuoka Prefecture for example boasted that it had built a bathing pool that could accommodate a thousand people.

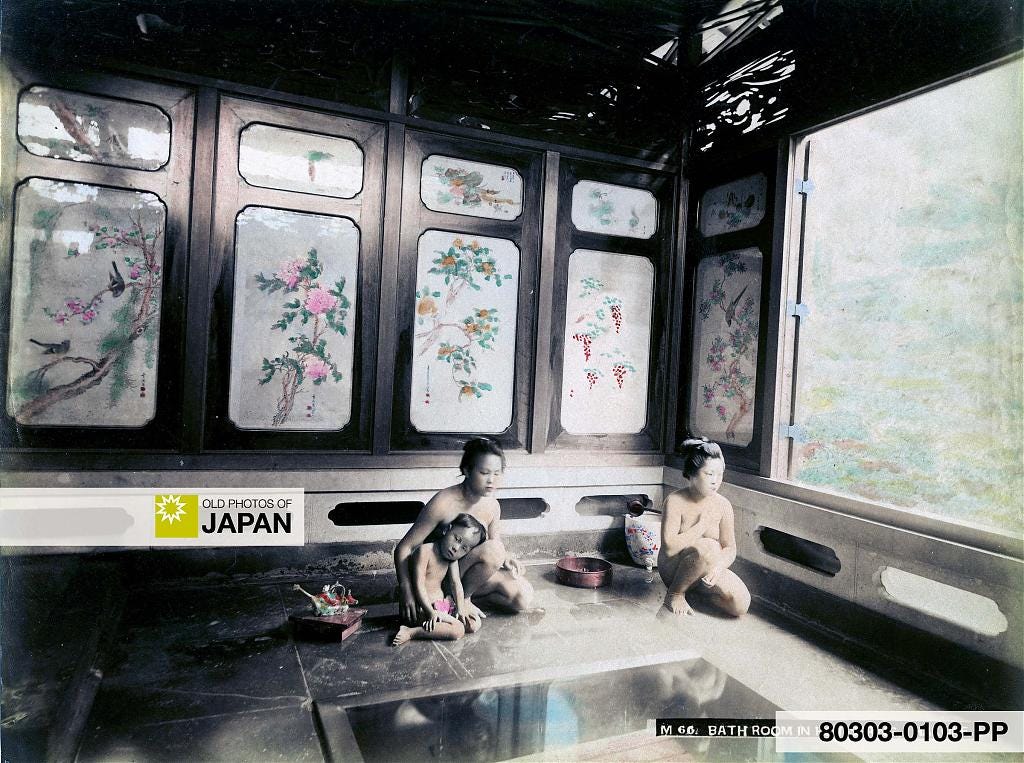

Private Baths

For many centuries, communal baths were the most common; it was economical to have the heated water used by a large number of people instead of just one or a few. But under pressure of the foreign gaze, communal bathing was looked upon with disdain after Japan opened its borders in the second half of the 19th century.

Officials in large cities like Tokyo and Osaka started to propagate against mixed bathing from the 1870s. These new “civilized” values imported from the West slowly spread all over the country. As a result, private baths started to gain in popularity.

By the early 20th century, private baths were already common enough for Japanese author Jukichi Inouye to describe them in Home life in Tokyo (1910):7

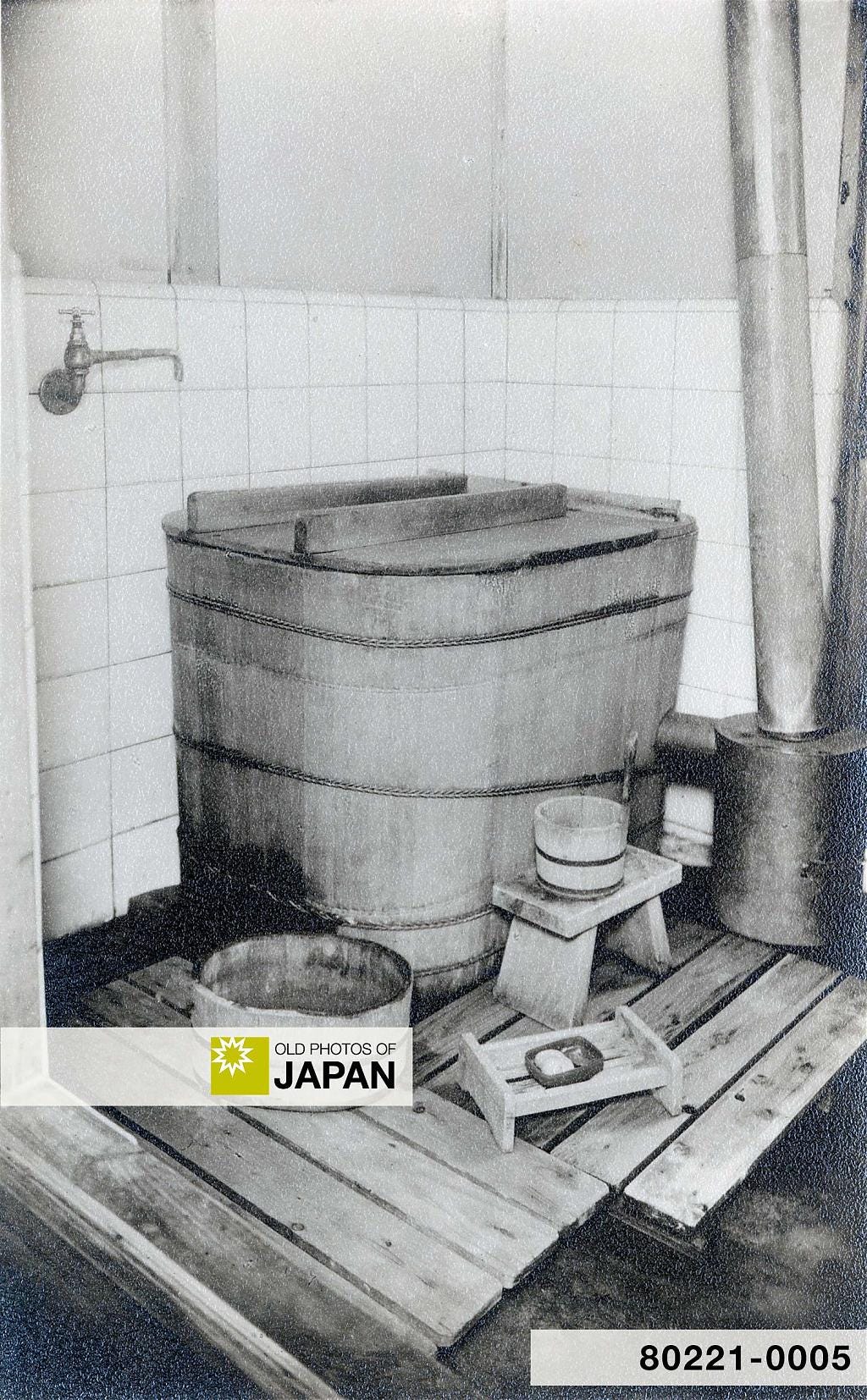

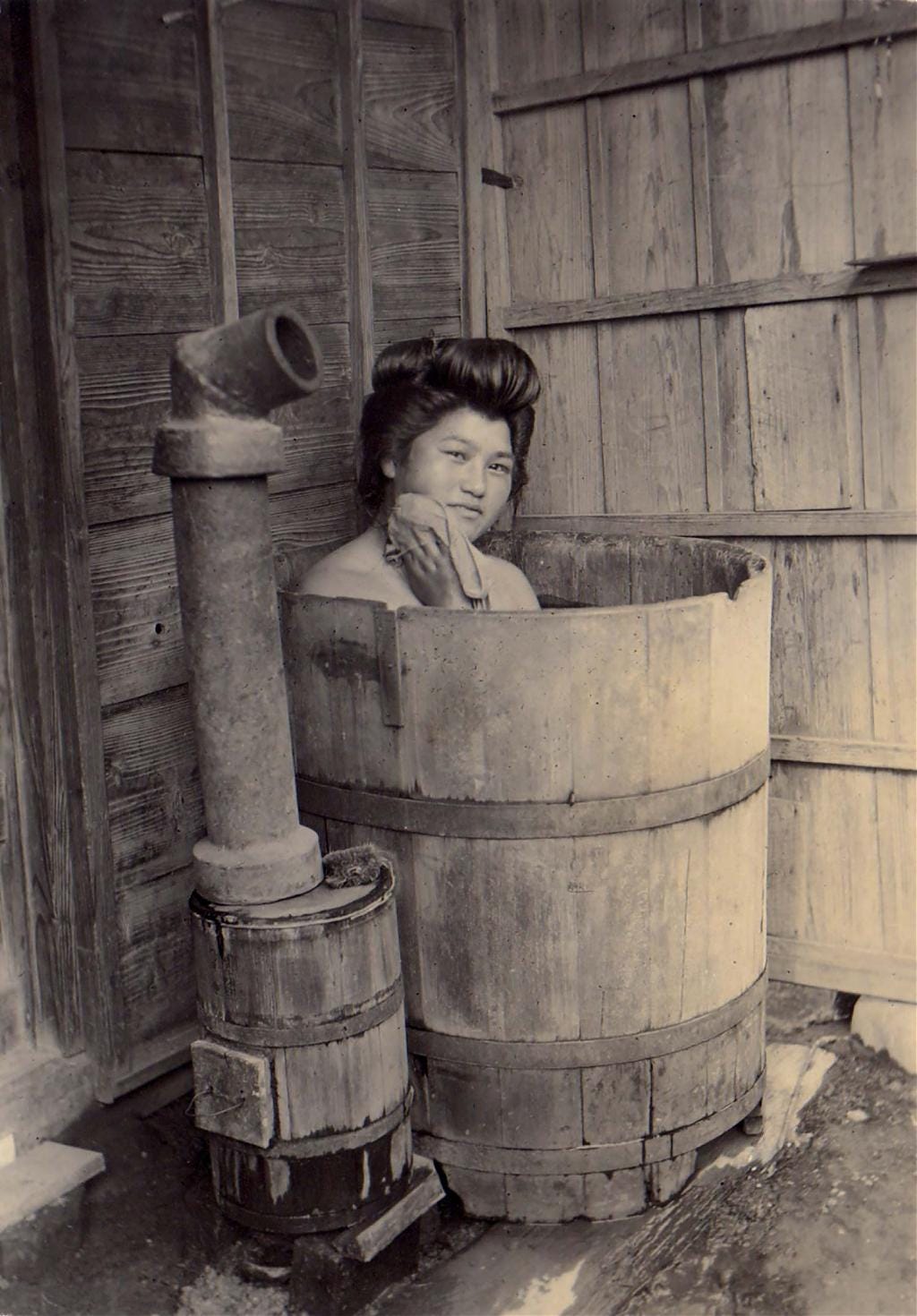

Public baths are, on account of their great convenience, largely patronised in Tokyo; but in many private houses bath-rooms are also built. A bath-room of the ordinary size is three yards by two. The bath of the commonest kind is made of wooden staves bound together with metal hoops. It is oval in shape and inside the bath near the edge a thin iron cylinder with a grating at its lower end passes through its bottom. Into this cylinder live charcoal is put in to heat the water of the bath; and a small plank partitions the cylinder to protect the bather from being burnt by contact with it.

Oblong baths are now made with thick wooden sides and a furnace at one end which is fed with coke or faggot.

The ground of the bath-room is paved with stone or beaten down with concrete; and on it stands a movable flooring, a foot or more high, of narrow planks with open spaces between to allow the water to run down.

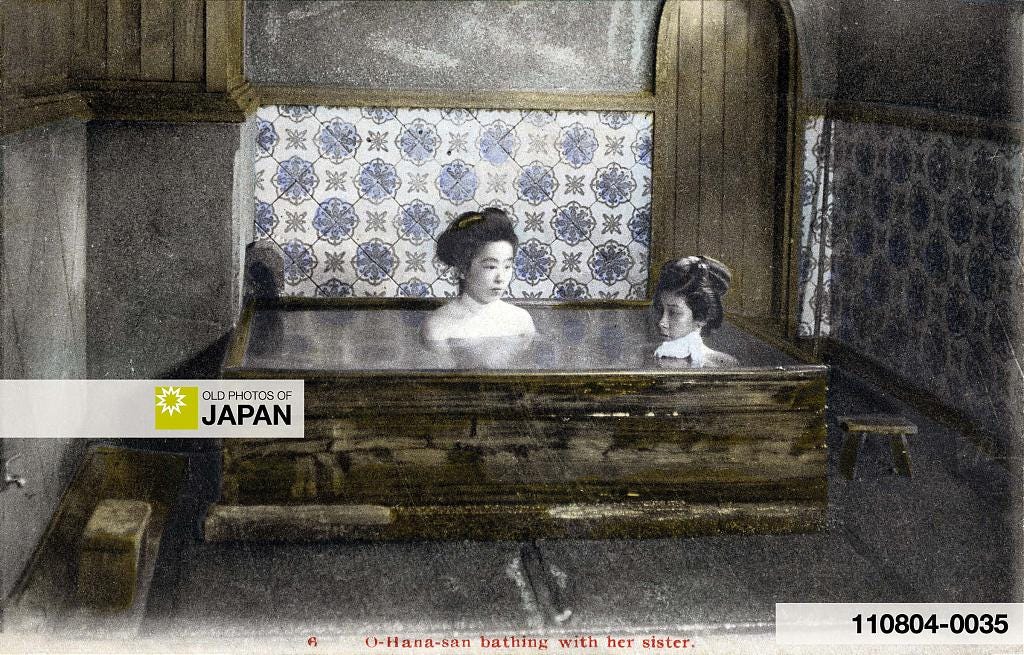

The bath holds one person or at most two spare persons, and the water in it is deep enough to cover the crouching body.

The bather always washes himself on the flooring and gets into the bath only to warm himself.

Jukichi Inouye, Home Life in Tokyo (1910), 55

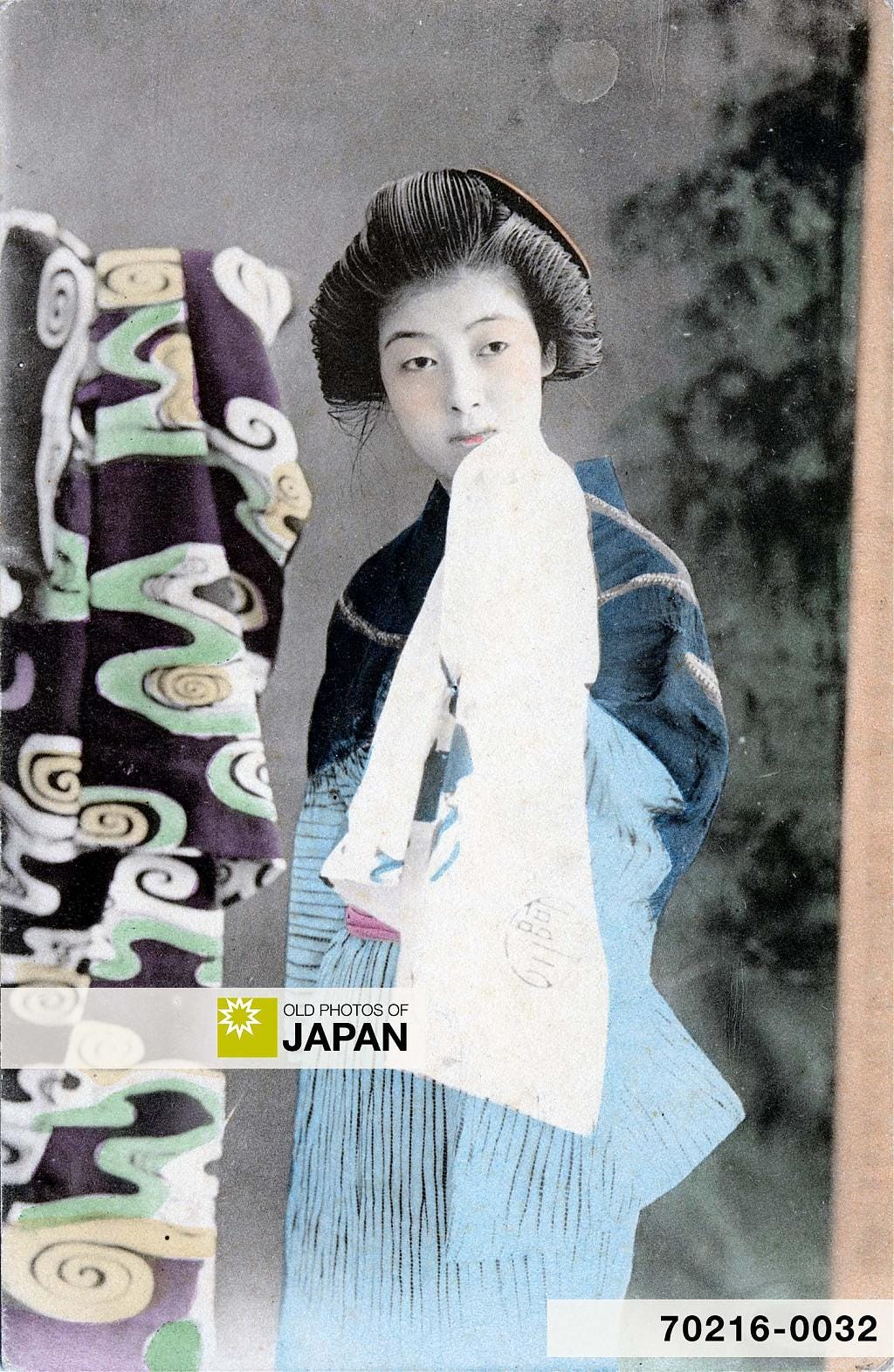

Interestingly, until the Meiji period (1868–1912), soap was not used in Japan. Japanese used rice bran. Women combined this with other natural products like crushed egg-shells and powered magnolia bark.8 Japanese cosmetics companies still produce skincare products from rice bran today. Such products are exported all over the world; soap was not a one-way exchange.

Soap is a foreign innovation; and the same purpose was served by the use of fine bran-powder obtained by sifting rice after its final cleaning in a mortar. A handful of this powder is put into a little cloth bag, which is then wetted and rubbed against the skin; and the turbid water which exudes through the texture of the bag is very efficacious in cleaning the skin. It is now used together with soap.

Young women sometimes put other substances with the bran into the bag, such as pulverised egg-shells which are said to remove stains from the skin and the powered bark of a species of magnolia.

Jukichi Inouye, Home Life in Tokyo (1910), 120

Small private baths meant that household members could not bathe together. A strict bathing order was enforced within each household. The household head went first, followed by the other males in the family, in order of descending age. After the men and boys were clean, the women and girls were allowed to enter the bath. This custom appears to be still upheld in many families today.

Inouye’s description of the bathing frequency brings a small surprise. These days, many Japanese seem to take baths more often in winter than summer. In an online survey, conducted in 2006 by Japanese internet research site DIMSDRIVE, only 33% of the 6,436 respondents answered that they soak in the tub almost every day during summer. For winter the figure was 69%.9

But a century ago this was the opposite according to Home Life in Tokyo: “It is the custom to take a bath every day in summer and perhaps once in two or three days in winter.”10 Likely, the ubiquity of showers and air conditioning has caused this change.

Thankfully, Inouye also wrote about public baths, allowing us to see how they were used over a century ago. The wife and children would visit the sentō during the daytime, he explained, before the rest of the family came home. Dinner was served after the bath.11

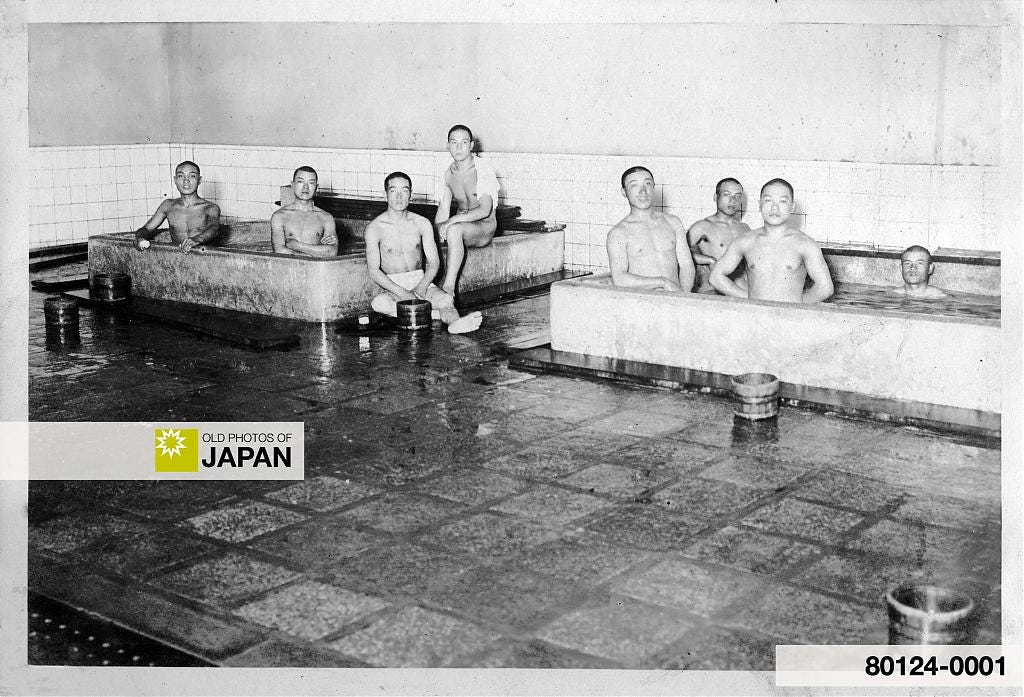

In the public bathhouse there are baths for the two sexes divided by a wooden partition, at the end of which the bathkeeper or his wife sits on a high platform so that both sections can be watched at the same time. There is in each section a single large bath, eight feet or more long by about four feet wide. Into this all the bathers dip up to their necks.

In front of the bath is a large slanting floor, on which they sit and wash themselves. Under the partition between the male and female baths is a square wooden tank each for hot and cold water. The water is ladled in little wooden pails. When we undress, we first wash ourselves on the inclined floor and then get into the bath; and when we have warmed ourselves, we come out and wash more carefully with soap and, in the case of women, with rice-bran powder as well.

When we have done washing, we get into the bath again, and finally, before we wipe ourselves on coming out of the bath, we pour again upon our bodies the hot water from the tank. We are then supposed to be always clean when we get into the bath; and as we do not wash in the bath itself, its water should always remain clear.

But as a matter of fact, the water grows turbid as the day wears; happily, the lights are dim when the bathhouse closes an hour or so before midnight. In the daytime it is pretty clean; and bathing in the forenoon is very pleasant as only a few bathers have been before us, except in the lower town where it is the custom for workmen to take an early morning bath.

Jukichi Inouye, Home Life in Tokyo (1910), 148–149

Bathing Today

Japanese bathing culture was brutally disturbed by the carnage of the Second World War. Most large cities were reduced to rubble, and bathing became a big problem. Many photos from this period show people bathing out in the open. People often resorted to using oil drums.

As a result, a house with a nice tiled bath now became the dream of many people, and thereby an important symbol of Japan’s recovery. It would take until the 1960s before people could start to make this dream a reality.

But progress differed enormously by region. In 1968, only 45% of dwellings in Tokyo had a bathroom, in Osaka the figure was even lower: 40%. Rural areas however had much higher percentages. The figure for Shizuoka and Yamagata prefectures for example stood at over 85%.

This trend continued. By 1983, the figures for Tokyo and Osaka were in the mid 70s, while in most rural prefectures they were near or exceeded 95%.12

Except for onsen, bathing is now mostly a private thing. In many areas communal bathing has vanished, or is in the verge of vanishing. Sentōs find it increasingly hard to survive.

The great increase of people living alone has also affected Japanese bathing culture. Surveys show that people living alone are less likely to use the bath tub. They often prefer a quick and easy shower.

Although Japanese bathing culture has greatly changed since the end of Word War II, it still plays a very important role in daily life. This especially becomes obvious when that daily life is interrupted by a disaster.

After the 1995 earthquake in Kobe and surroundings, people crowded into the communal baths in large tents set up by the Japanese Self Defense Forces. And after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Tohoku, I ran into a makeshift bath with steel drum cans—just like those after World War II—in the small town of Rikuzentakata in Iwate prefecture.

The joy in the eyes of the people when they stepped into the piping hot cleansing water was a true pleasure to behold.

Related Articles

Kaempfer, Engelbert (1906). The History of Japan: Together with a Description of the Kingdom of Siam 1690–92, Vol. III. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons, 291.

Kaempfer, Engelbert (1906). The History of Japan: Together with a Description of the Kingdom of Siam 1690–92, Vol. II. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons, 367.

Clark, Scott (1994). Japan: A View from the Bath. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1.

Before I emigrated to Japan in 1982, a Japanese person asked me how to say “warm water” in English and got thoroughly upset when I answered “warm water.” To her, warm water was a separate almost sacred entity, not to be lowered to the level of common unheated water. She thought I was being rude by not telling her the word.

Butler, Lee (2005). Washing off the Dust: Baths and Bathing in Late Medieval Japan. Monumenta Nipponica, 60(1), 2–4. Retrieved on 2022-04-18.

ibid, 8, 35.

Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 55.

ibid, 120.

INTERWIRED.CO.,LTD. ネットリサーチのDIMSDRIVE『バスタイム』に関するアンケート Retrieved on 2022-04-08.

Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 148.

ibid, 148–149.

Clark, Scott (1994). Japan: A View from the Bath. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 61–62.

Thank you very much for restacking.

Winter is probably the best time to read this article. The extreme warmth of the water of a Japanese bath, and the wonderful feeling of community of its public baths, warm both body and soul.

On note 4: of course we don’t understand hot water as a separate word. We are barbaric.