1900s • "The New Year in Japan"

This article reproduces a 1906 photo book introducing Japanese New Year customs.

A woman paints the face of a boy who lost in the card game of karuta. Photographer Teijiro Takagi shot this scene in Kobe in 1906 for a photo book about Japanese New Year celebrations.

Read this article on the site | Comment on this article.

This article reproduces Takagi’s book. Titled The New Year in Japan, it features 24 collotype photos illustrating how in the early 1900s an average Japanese middle class family in Kobe spent the last days of the old year and the first days of the new one.

Each photo is accompanied by a brief description. This book was published in February, so it most likely shows scenes from the last days of 1905 and the start of 1906. It is rare to be able to date and locate vintage images this precisely.

New Year celebrations are far more important than any other celebration in Japan. This was even more so in the past when preparations started at least a week in advance.

New Year celebrations originally had a close connection with the challenges of agricultural life. They therefore had a strong spiritual element. But from the early 1800s on, and especially during the Meiji Period (1868-1912), New Year celebrations were increasingly urbanized and the mysticism vanished.

Although increasingly forgotten by city dwellers, memories of New Year’s spiritual origins continued to exist well into the 20th century. In his 1926 autobiography, Toshihiko Sakai (堺 利彦, 1871–1933)—an activist, writer and historian involved in the founding of Japan’s Socialist and Communist Parties—beautifully described how he experienced this mysticism as a young boy:1

New Year’s eve was certainly a time fraught with importance, and only a somewhat old-fashioned expression like “fraught with importance” can really do it justice.

First we lit a certain number of lamps and set them on the shelf containing the representations of the tutelary gods of our home. As I gazed at them, my child’s heart was purified to its very bottom by their bright gleam. Next we placed more lamps in a number of places, inside and outside the house, in the decorative alcove, on the kitchen range, on the mill, on the well, and in the privy.

These were not like those on the shelf for the tutelary gods, but were of a special temporary construction. What we did was to take a large white radish, cut it into one-inch lengths, hollow one end of each of them out a little, pour in oil, and add wicks, which we then lit.

I will never be able to forget the feeling of a kind of supernatural mystery and of a solemn grandeur, which I would experience when coming into a room illuminated with these radish-lamps. My feelings were especially marked when I went into the kitchen, or the mill, or to the well, or to the privy surrounded by the pitch-blackness of night. As we sat quietly in the kitchen, the lights all over the house gleamed and shone; it was a feeling of a very special kind of illumination.

Autobiography of Toshihiko Sakai (1926)

By the time Takagi published his photo book about New year celebrations, few city dwellers would have been aware of such practices. His book therefore introduces a thoroughly urban way of celebrating. So urban actually that many aspects are still in use today.

Takagi’s book has been reproduced below with the original captions in italics. The titles, and non-italic explanatory notes, are mine.

The New Year in Japan

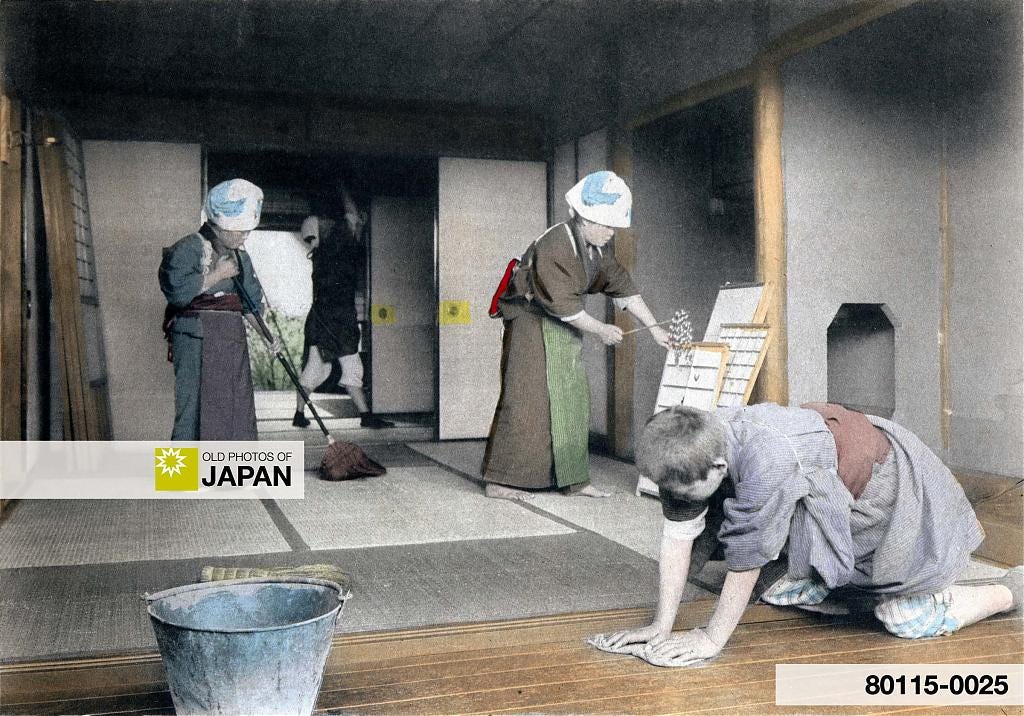

1. Osoji : Year-End Cleaning

A preliminary to the coming of the New Year is a general “spring cleaning,” as our friends term it. The interior and exterior of every domicile is cleaned and re-decorated. Warehouses and business houses all undergo a similar “clean out,” and we get ready for a new lease on life.

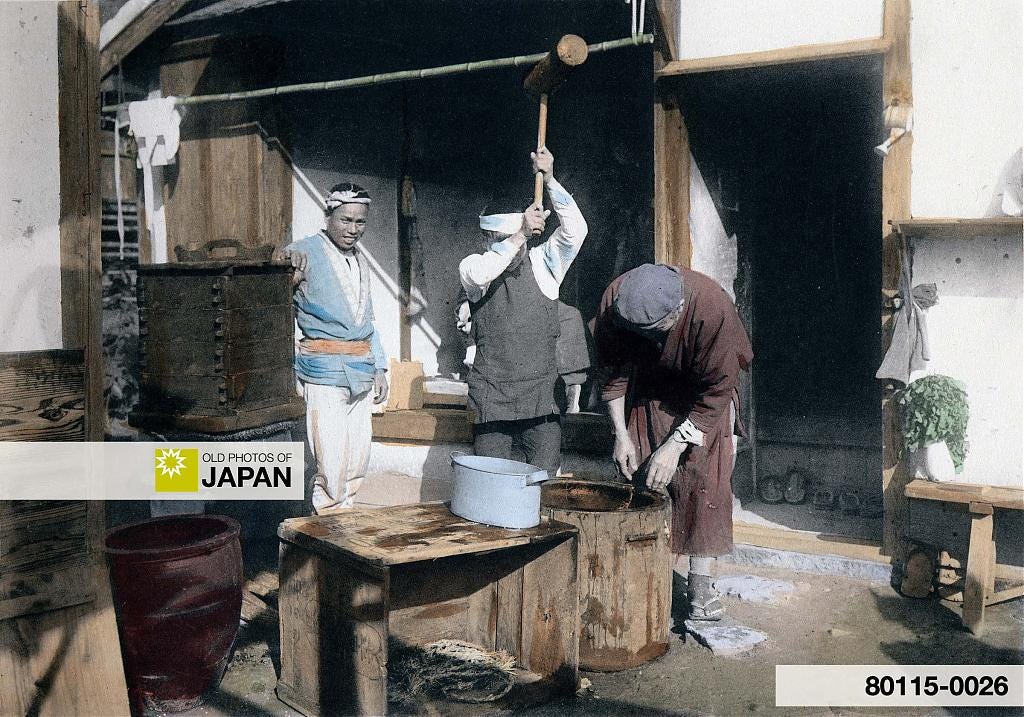

2. Pounding Rice for Mochi

Our foreign friends indulge in plum pudding; our pudding, mochi (a dough of rice), is the national diet for the celebration of the New Year Era, and also for sacred celebrations during the year. Men, with boilers and dough tubs, pound the rice into dough, and nearly every family engage these dough pounders, to save time and trouble. The pounding begins about the 25th December, and continues until the end of the year.

3. Bamboo Decorations

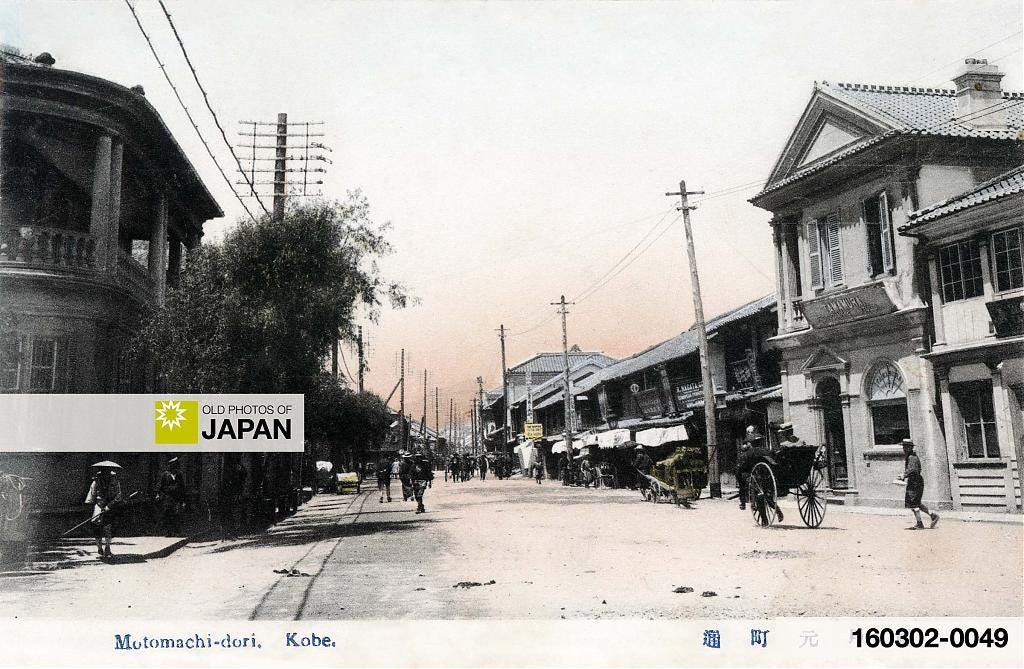

Bamboo poles are to be seen, erected on the eaves of various shops, to remind one of the Toshino-ichi (the New Year’s Fair), which is now in progress. The shops are also decorated in Christmas style, for the purpose of supplying foreign residents with all they may need for the festive Xmas season. The Japanese wives may be seen hurrying here and there to obtain geta, and many other items necessary for the family to bloom forth in fresh raiment on New Year’s Day.

4. Year-End Market

At other fairs, articles are arranged in booths, in Temple grounds, and here you may obtain, practically, anything, you require, and many, many people buy what they do not really need, but the attraction is cheapness, and that is a strong magnet with humanity in general!

5. Decorations

At other stalls we see Kazari (new rice straw) rope, in lengths, intertwined with fern-leaf and evergreens for the New Year adornment of dwellings and business concerns, emblematical of a new Era, The New Year.

6. New Year Plants

And now, the household must see about procuring a pot or two of the ‘Prosperous Age Plant,’ to complete the attractions of the interior of their ‘Home Sweet Home,’ and minature [sic] pine trees, and bamboo plum twigs are also used for decorative purposes.

7. Eating Soba (Buckwheat Noodles)

The last hours of the old year are speeding on their journey into oblivion; the disagreeable task of demanding payments of old debts is finished, and just before the year expires, the family and the domestics meet together in mutual harmony, to partake of (Japanese) macaroni [soba]. Ah! The clock strikes out the death knell of the old year; the assembled ones remain silent, absorbed in thought, for a moment or two, and then take a very brief rest, ere they awake in the early morn to welcome the New Year and to perform the many, many customs handed down from a period immemorial.

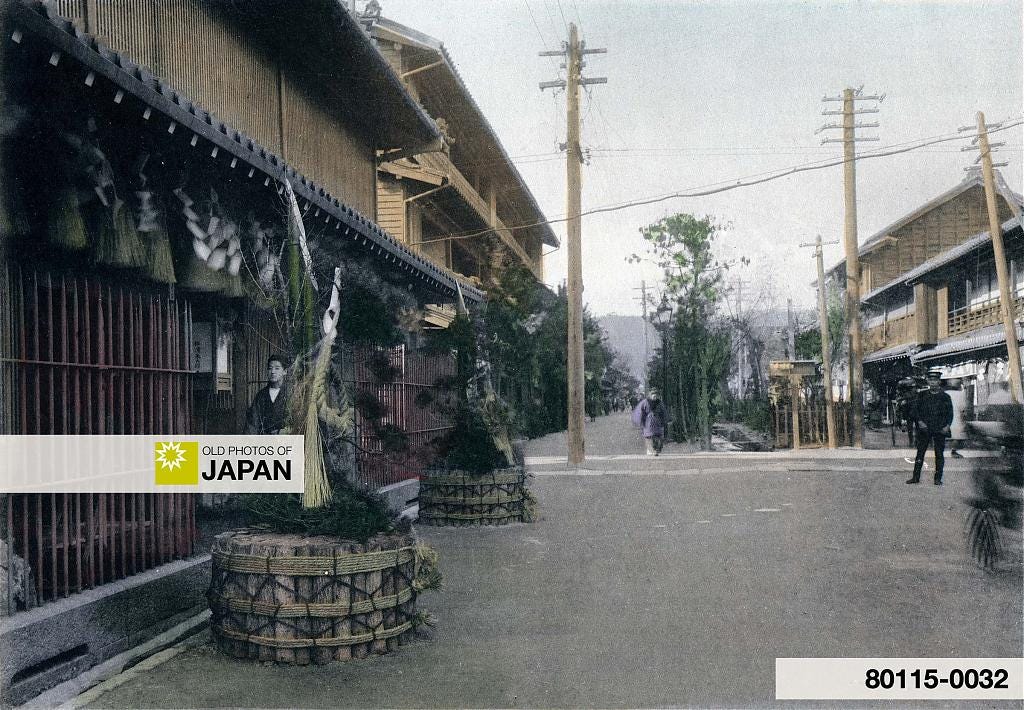

8. Kadomatsu

It is barely daylight, and already the people are emerging from their homes, to inhale the fresh air of a New Year (and winter, in Japan, is but a kind of cold summer, so far as blue skies is concerned), and to pay complimentary visits (a veritable boredom to many level-minded people) to folk they greet thus but once a year! Please observe the bamboo decorations in front of each dwelling.

Kadomatsu (door pine) is a decoration specifically designed for Japanese New Year. They are displayed next to the entrance during the first week of the year.

The pine represents continuity, the bamboo straightness and sincerity. Kadomatsu can be seen all over Japan, except near Ikuta Jinja in Kobe. Reportedly because the kami of the shrine showed his dislike of kadomatsu by washing the ones near the shrine away during a flood in the eighth century.

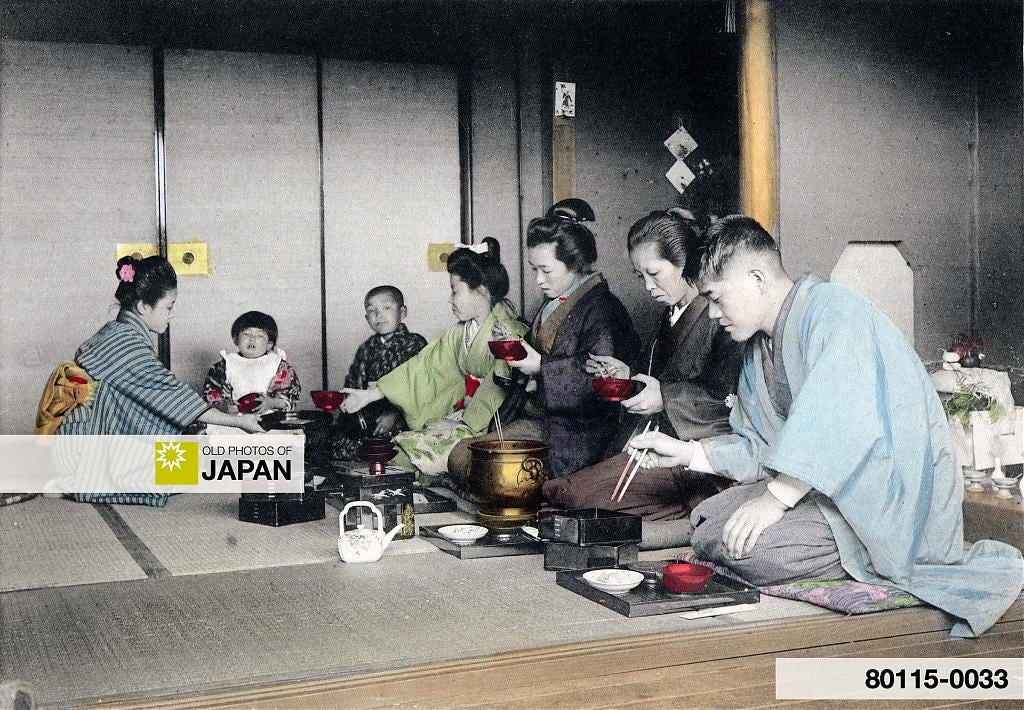

9. First Meal of the Year

This illustration is a general representation of every family in Japan, partaking of the ceremonial breakfast, the members of the family congratulating each other, and ‘toasting’ each other in cups of zoni, a beverage made from mochi (boiled rice dough) and this ceremony is repeated until the third day of the New Year.

Mochi rice cakes are still used in traditional New Year dishes today, including zoni soup. Sadly, every year the Japanese news media report about people choking to death from eating this delicacy. The sticky mochi are difficult to chew and can easily get stuck in the throat.

A study about food choking deaths in Japan between 2006 and 2016, found that such deaths peaked every January.2 The study did not attribute the deaths to particular food items, but the authors suspected that many of the annual 4,000 food choking deaths were related to mochi.

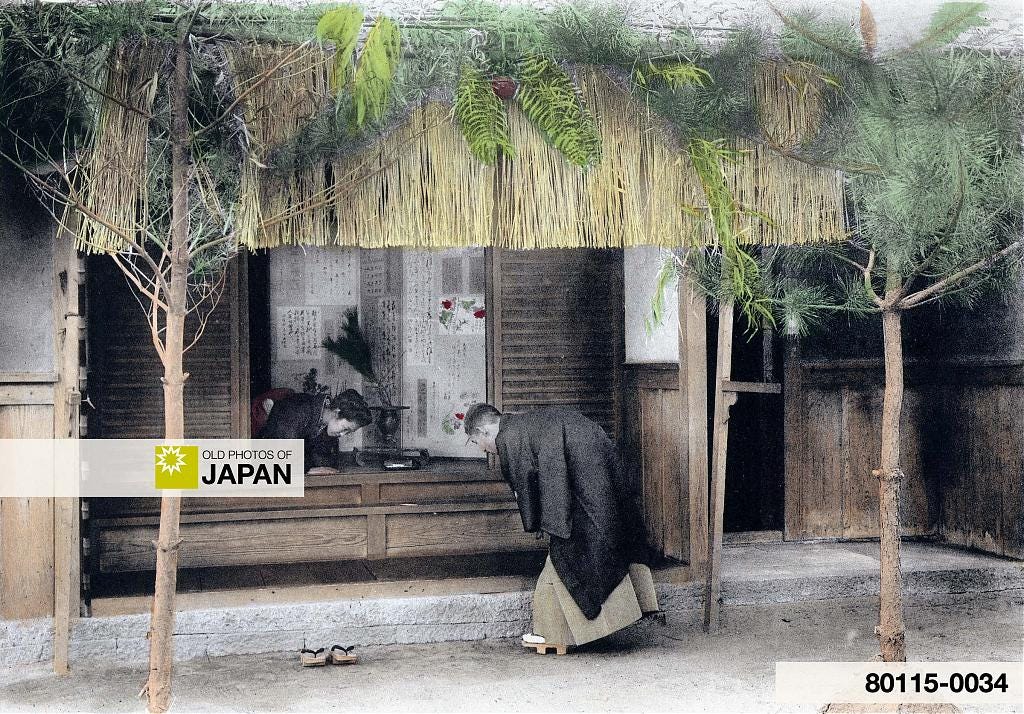

10. First Greetings (Aisatsu)

The ceremonial breakfast having been disposed of, the members of the family sally-fort to pay their respects to their friends. Merchants (or their representatives), dressed in faultless attire, call upon their friends and customers, and leave cards, or give a personal greeting. Friends and enemies (for the moment) are reconciled, and people who were wrangling with each other on the last day of the old year, are now indulging in hypocritical smiles, and an old Japanese maxim hath it: ‘Ye, the devil of the eve, comes for homage in the morn!

Out of this custom, the more convenient modern custom of sending New Year cards was born.

The New Year cards, or nengajo, that are delivered during the first three days of January became popular after the Japanese post office began issuing postcards in the Meiji Period.

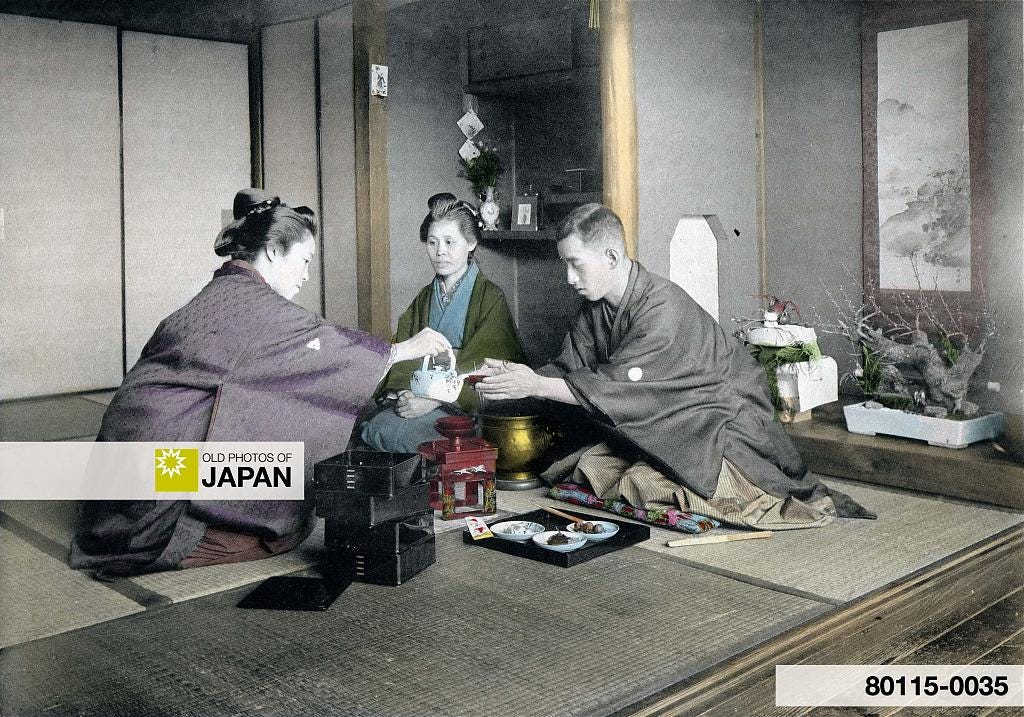

11. Entertaining Guests

The more intimate and specially favoured friends are invited to enter the best room, which is elaborately decorated in the space known as ‘the place of honour,’ and the guest is invited to partake of toso3, a kind of wine.

Entertaining close friends took place in the best room of the house, with the friend sitting in the place of honor in front of the tokonoma.4

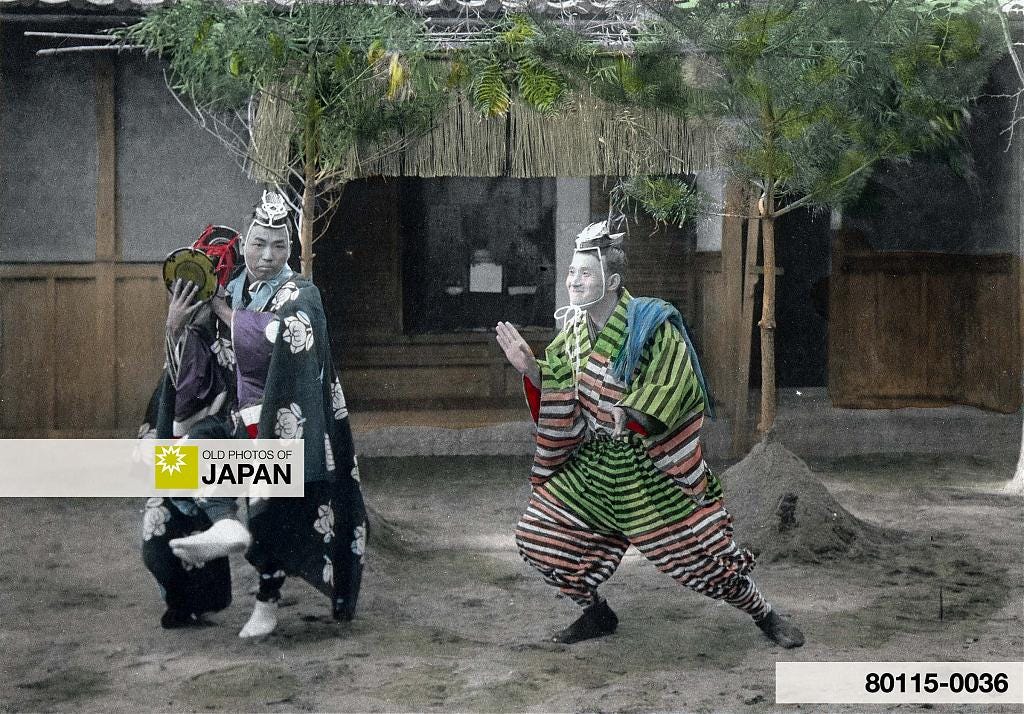

12. Street Entertainers

Ping! Pong! These men are acting similar to the foreign pantomine [sic] clowns; they parade the streets, performing various antics, peculiar to custom, and they shout “Hail! Hail! ye Gods of Heaven and earth. Significant omens are in the air, and the universe is full of lucky signs.”

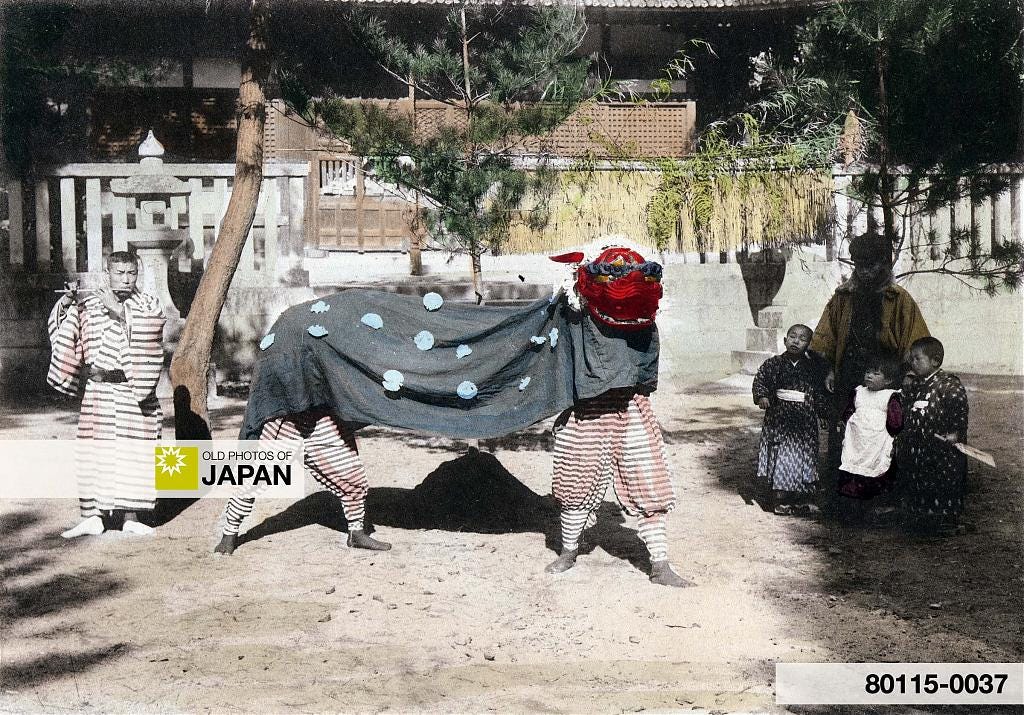

13. Lion Dance

To the accompaniment of a flute and a drum, the ‘lion dance,’ is being given; but the “lion” is a two-legged one, somewhat weaker than the “King of the forest.”

These men perform a shishi-mai lion dance in the courtyard of a shrine. The performers would also dance in front of the homes of the parishioners as a charm against evil spirits and disease, and to pray for good fortune.

Shishi-mai probably entered Japan around the 8th century after Japanese diplomats and priests encountered them in China. They are still performed today and it is believed that some 9,000 different variations of shishi-mai exist.

14. Fun for the Kids

Here is another attraction for the special entertainment of ‘Young’ Japan; it is ridiculous to the adult eye, but we ourselves were young at one time!

While most of the other customs in this series are still observed, this entertainment for the kids seems to have vanished.

15. Temple Market

The temple grounds are thronged with visitors, bent upon paying their devotions to the Gods and the Souls of long departed heroes. We are hero worshippers, and Admiral Togo will, in the fulness of time, be worshipped in like manner; his soul supposed to be resting within the sacred precincts of the Temple specially dedicated to his memory. Here you will observe all sorts and condition of natives purchasing “lucky” mementoes of the New Year.

Even today, many temple grounds are crowded with all kinds of stalls during the first days of the year.

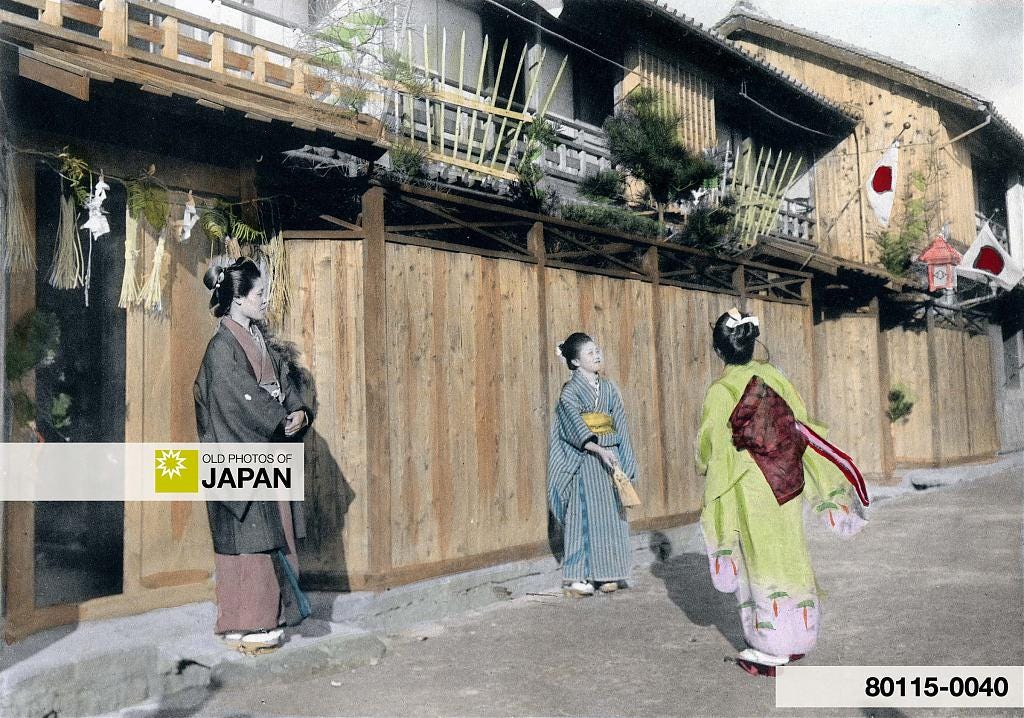

16. Battledore and Shuttlecock

Attired in her best kimono (dress) and obi (band), Ohama San calls upon her friend Otama San to join her in a game of battledore and shutlecock [sic], this being a three day custom of the beginning of the New Year.

Hanetsuki (羽根突き, battledore and shuttlecock)5 was one of several traditional games played during the New Year celebrations.

There are two ways to play this: one person keeps the shuttlecock aloft as long as possible, or two people bat the shuttlecock at each other.

17. Flying Kites

The wind is good, and boys are quick to take advantage of it. They rush away with their kites, with almost naked legs (the Japanese boy is impervious to the effects of heat or cold), and, braving the chilly blast, they scream with joy and pride as they view their kites so high.

As someone who flew kites a lot as a kid, I am sad to say that this custom has almost completely disappeared.

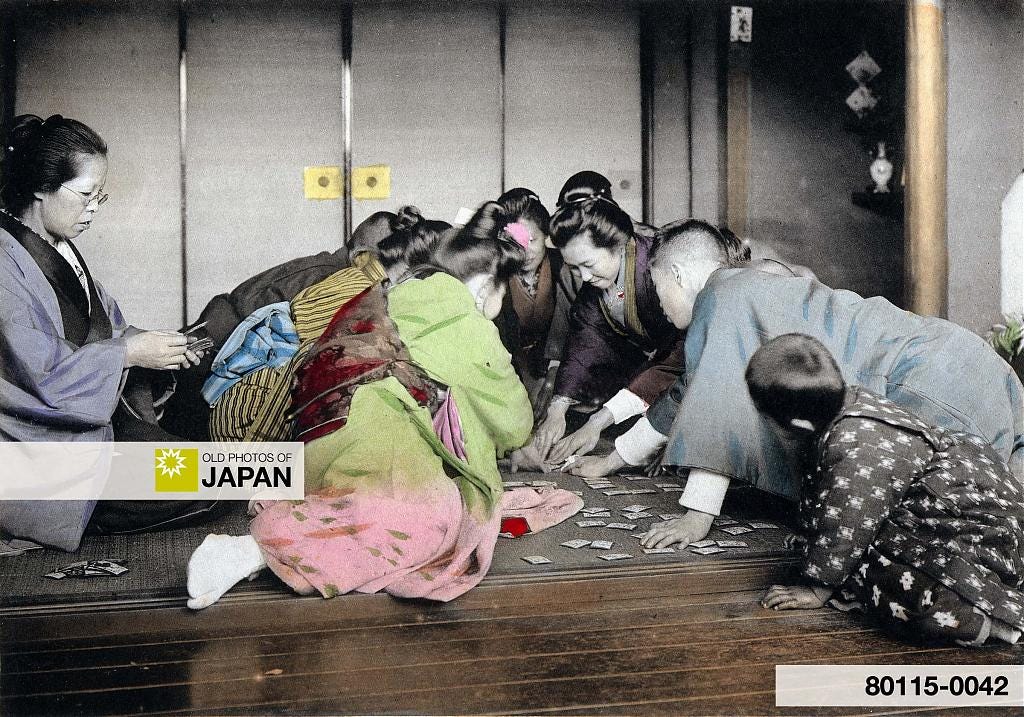

18. Playing Karuta

In the evening, the members of the family, irrespective of age, join in the New Year Card Game, which is played only on this occasion. The game is to pick out cards containing the last characters of a poem; it is a somewhat complicated game, and causes much amusement.

Karuta (かるた), is still played by some families during New Year today. In this card game, one person reads the start of a poem—taken from the Hyakunin Isshu waka anthology—written on cards called yomifuda (読札, reading cards).

On the floor, torifuda (取り札 or grabbing cards)—cards with the end of the poem—are spread out. The aim of the game is to be the first to grab a torifuda card after a yomifuda has been read out, and to collect as many cards as possible during the duration of the game.

Every January 3rd, Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto hosts the first Karuta game of the year, known as Karuta Hajime Shiki (かるた始め式, First Karuta Ceremony). The players are women aged between 8 and 25 dressed in Heian Period (794-1185) Juni-hitoe court costumes.

Karuta is a sport as well as entertainment. Japan hosts sixty tournaments of Kyogi Karuta annually.

19. Getting “Branded”

The ones who have shown the least skill in playing must submit to being branded with a mark of ‘disgrace;’ this being a dab of ink, and applied to the face in such a manner as to deprive one of all dignity—for the time being; it is good fun, and many of them prefer playing badly, in order to receive the “decoration” of the dunce!

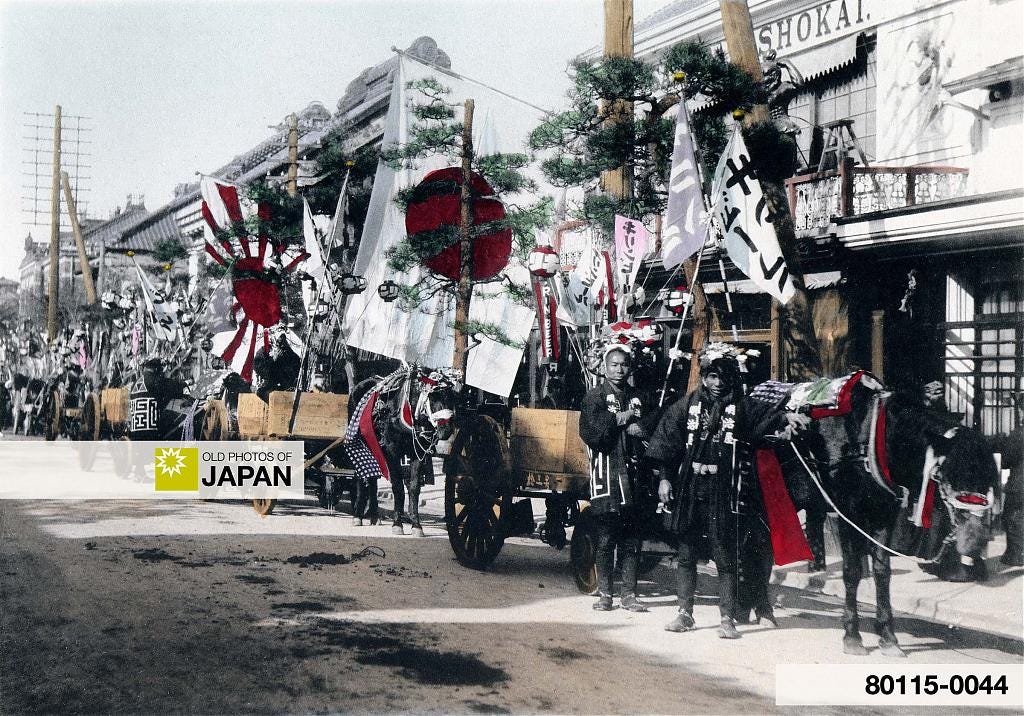

20. Merchant Procession

This picture represents the early morning of the second day of the New Year, and we observe a procession of carts, representing various merchants, merchandise and products. The coolies are in a special uniform peculiar to the occasion, and the show is emblematical of the New year’s first trade, and it is also a grand advertisement for the merchant who cares to take part in this ancient custom.

This is a New Year custom that has completely vanished from Japan’s streets.

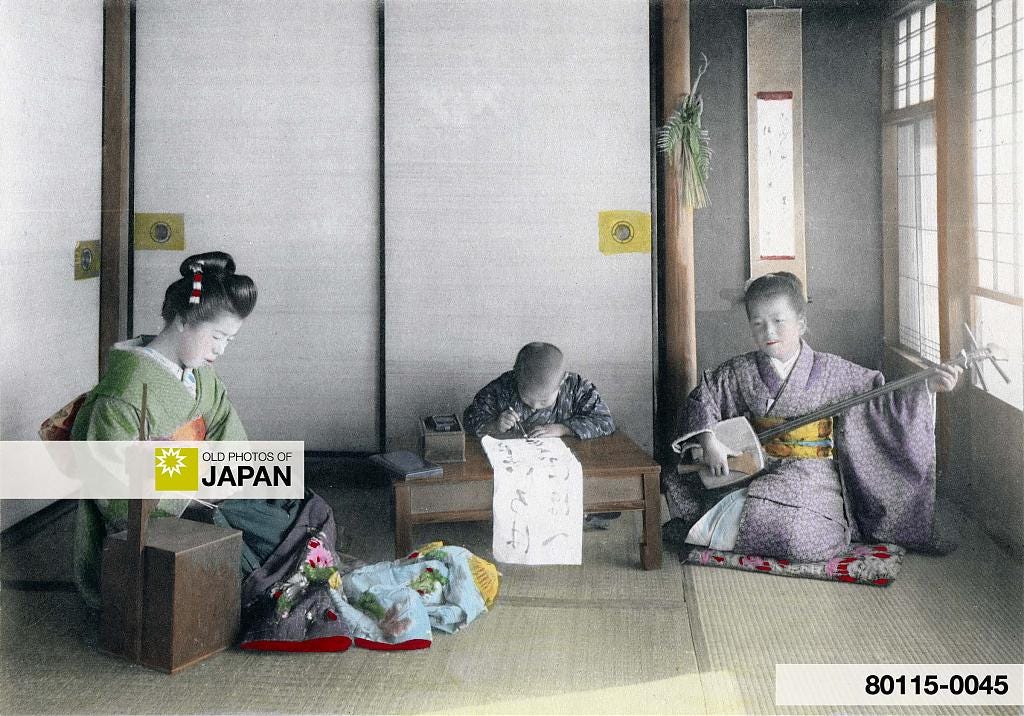

21. First Chores of the Year

The elder daughter plies her needle, in token of her good resolutions of the New Year, and the younger is likewise employed, but with a musical instrument, the samisen [sic], while the wee brother is occupied in making his copy of characters (our substitute for words) to show his teacher.

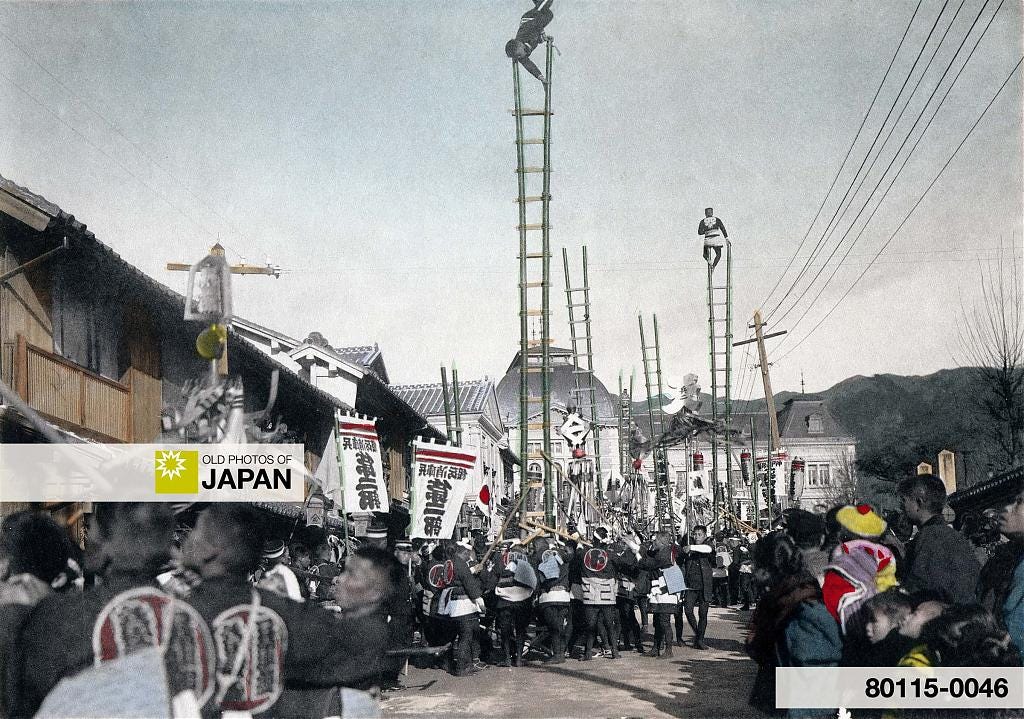

22. Firefighters Show Off

On the fourth day the fire brigades give practical illustrations of their capabilities. Engines are screaming along the street; ladders are lashed together in a moment or two, held high in the air, and then the younger members imitate the moneky family by rushing up to dizzy heights, and in no hurry to come down—a well-known habit of the real “Jacko.” The men are given presents of money, and are regaled with wine, and then they get home just in time to prevent “accidents.”

Firefighters in happi coats performing acrobatic stunts on top of bamboo ladders were the main event of Japanese New Year celebrations.

The demonstrations, called dezome-shiki, were intended to warn people of the dangers of fire, and to demonstrate the agility and courage of the firefighters.

The old Japanese way to fight fires was to tear down surrounding houses, so ladders were needed to climb on roofs. Because of the climbing involved, especially scaffolding workers served as firemen. They had incredible strength and stamina because of having to build scaffolds on a daily basis. The demonstration was preceded with the firemen praying at a shrine for their safety during the coming year. Dezome-shiki are still held at many towns today.

In the back of the photo, Hyogo Kencho can be seen, making it possible to actually locate the place where this event took place, likely on January 4, 1906.

23. Purification Fires

The New Year holidays end on the 15th of January, and the next day the decorations of the interior of houses are taken to the Shinto Temples, where the Priest blesses the tokens, and the floral matter is then committed to a fire. This pleases the children, they not understanding the purpose of the ceremony.

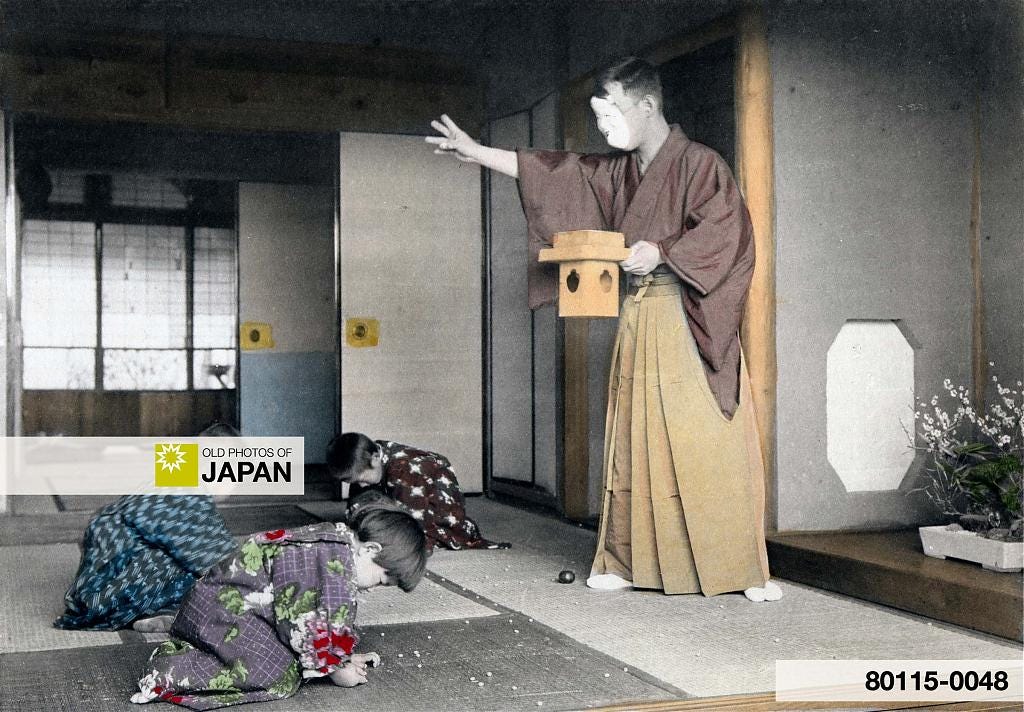

24. Setsubun

On the fourth of February another celebration takes place; this being a sport for children, in the form of scrambling for bean [sic], thrown by a man wearing a mask, the latter representing the “God of Fortune.” The beans are thrown high and low in all directions, the “God” exclaiming:

“The God of Fortune shall stay;

The devil shall be driven away!”

Very few people today would consider Setsubun as part of the New Year celebrations. But it seemed perfectly natural to Takagi to include this ceremony when he put this book together in 1906.

Setsubun is the day before the beginning of each season, but the term is generally used mainly for the spring Setsubun, celebrated at the start of February. Traditionally, Setsubun was seen as a way of cleansing away the previous year as spring approached.

Note

These images were previously published individually on Old Photos of Japan. But I considered it important to put them all together, as they were originally published in a single book.

About the Photographer

[ This section was previously published in The Rice in Japan and The Ceremonies of a Japanese Marriage. ]

Although Teijiro Takagi (高木庭次郎) was extremely productive and active for some two decades, surprisingly little is known about his life. So little that he has even been described as a phantom photographer (幻の写真家).6

Both his dates of birth and death are still unknown, although he was probably born some time between 1872 (Meiji 5) and 1877 (Meiji 10). His somewhat better known father Kichihei (高 木吉兵衛, ?–1882) was also a photographer.7

Takagi studied under Kozaburo Tamamura, and worked as the manager of Tamamura’s branch store in Kobe. He is first listed as the owner of this store in the Japan Directory of 1904 (Meiji 37), suggesting that he took the business over in the preceding year. He continued to use the Tamamura name until 1914 (Taisho 3).

According to research by Terry Bennett, the Takagi studio continued until at least 1929 (Showa 4), with locations in Kyoto and Kobe. An edition of The Tea in Japan, photographed by Takagi, shows 1927 (Showa 2) as the date of publication.

But research by Robert Oechsle has uncovered a notice published by Takagi successor Futaba Shokai that it took over Takagi’s business on March 4, 1924 (Taisho 13). The new owners were his former employees.8

Takagi published at least thirty photo books that introduced Japanese life and customs in English, all of them with hand-colored collotype prints like the ones featured in this article.

He also produced a very large number of glass lantern slides. These hand-colored slides are of extremely high quality, comparable to Nobukuni Enami’s work.

Below are some of the photo books published by Takagi, initially under the Tamamura brand name. The books marked with ✷ are in my collection.

1904 Leaf From the Diary of a Young Lady

1905 The Ceremonies of a Japanese Marriage ✷

1905 From Peace to Strife, An Incident of the Bushido Spirit

1906 The New Year in Japan ✷

1906 The Festival of the Ages

1906 The Great Gion Matsuri

1906 The Fishermen's Life in Japan

1906 Views in the Land of the Rising Sun

1906 The Japanese Tea-House (The Social Restaurant)

1907 The School Life of Young Japan ✷

1907 The Rice in Japan ✷

1907 The Transformation of Mother Earth from Nature to Art (pottery making)

1907 The "Ceremonial Tea" Observance in Japan ✷

1907 The Chrysanthemums in Japan

1907 In and Out of Kobe

1908 Snap-shots of out-door life in Japan

1909 A Wintry Tour Around Fujiyama

c1909 Artistic Japan

c1909 Picturesque Japan

1910 Girls' Pastimes in Japan

c1910 Japanese Views and Characters (three volume set)

c1912 Three Mischievous Children

1913 The Building in Japan

1915 The Silk in Japan

1915 Hills of Kobe

1917 The Fujiyama

1918 Military Accomplishments of Japan

c1918 Views of Kioto

c1919 Famous Scenes in Japan

1920 Characteristic Gardens in Japan

Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 274–275. 堺利彥(1926年)。

堺利彥傳(Sakai Toshihiko Den)、東京:改造社(Kaizōsha)。

Taniguchi, Yuta, Iwagami, Masao, Sakata, Nobuo, Watanabe, Taeko, Abe, Kazuhiro, Tamiya, Nanako (2020). Epidemiology of Food Choking Deaths in Japan: Time Trends and Regional Variations. Journal of Epidemiology. Retrieved on 2022-12-28.

Toso is spiced medicinal sake.

The Tokonoma is an alcove in a Japanese-style reception room used to display valuable or artistic items (see 1890s • Woman in Room).

Hanetsuki is a traditional Japanese game. Similar to other racket games, it is played with a rectangular wooden paddle called a hagoita and a brightly colored shuttlecock. However, there is no net.

石田哲朗(2015)。高木庭次郎の幻灯写真:収蔵作品《日本風景風俗100選》について。東京都写真美術館、101–102.

Bennett, Terry (2006). Photography in Japan 1853–1912. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 294–195.

Baxley, George C. Color Collotype Books by Tamamura & Takagi, Kobe. Retrieved on 2022-03-07.